Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

It was a hot day in 1969 in the Mexican state of Puebla. At the Great Pyramid of Cholula, Mexican archaeologist Ponciano Salazar Ortegón was digging 25 feet down on the side of what archaeologists call Building 3 1-A. Part of a building’s talud structure collapsed and exposed a curious and vibrantly painted mural. When completely clear of dirt and other debris, the panting measures 187 feet across and is considered to be the longest ancient mural ever discovered in Mexico. It dates to about 200 AD. The mural’s subject is an elaborate banquet. The people depicted therein are in various stages of intoxication and some have drinks in their hands. Archaeologists unanimously agree that the revelers are engaging in one of the earliest known depictions of the ritual drinking of pulque, a uniquely Mexican drink,

It was a hot day in 1969 in the Mexican state of Puebla. At the Great Pyramid of Cholula, Mexican archaeologist Ponciano Salazar Ortegón was digging 25 feet down on the side of what archaeologists call Building 3 1-A. Part of a building’s talud structure collapsed and exposed a curious and vibrantly painted mural. When completely clear of dirt and other debris, the panting measures 187 feet across and is considered to be the longest ancient mural ever discovered in Mexico. It dates to about 200 AD. The mural’s subject is an elaborate banquet. The people depicted therein are in various stages of intoxication and some have drinks in their hands. Archaeologists unanimously agree that the revelers are engaging in one of the earliest known depictions of the ritual drinking of pulque, a uniquely Mexican drink,

Here is what the Ancient History Encyclopedia online has to say about pulque:

“Pulque is an alcoholic drink which was first drunk by the Maya, Aztecs, Huastecs and other cultures in ancient Mesoamerica. Similar to beer, it is made from the fermented juice or sap of the maguey plant (Agave americana). In the Aztec language Nahuatl it was known as octli and to the Maya it was chih. Only mildly alcoholic, the potency of pulque was often increased with the addition of certain roots and herbs.”

Pulque makers use six different types of maguey plants to make this milky-white intoxicating beverage. The maguey, also called agave, is better known to English speakers as the century plant. The plant is a hardy desert-dweller found in the dry mountainous regions of Mexico and in parts of the American Southwest and Texas. Although the century plant only lives to about 30 years, near the end of its life cycle it sends up a characteristic flowering stalk that can reach over 25 feet in height. The Spanish called the plant maguey which comes from the language of the Taino people, the indigenous group the Europeans first encountered in the Caribbean. The Aztecs called the century plant metl. To them, the maguey had many uses. Fibers from its tough spiny leaves were used to make rope or fabric for clothing. The ancient Mexicans used the hard outer membrane of the leaves to make paper. These membranes were also used in cooking. Not leaving much to waste, the thorns of the plant made excellent sewing needles or were used as small tools to make punctures. To make pulque from the agave, cultivators cut off the flower stalk to leave a depressed surface measuring about 12 inches in diameter. It is in this depressed surface where the sap of the agave, called aguamiel, literally “honey water,” collects. Pulque producers gather this sap twice a day and an average plant produces aguamiel throughout a 6-month period before the agave dies. In ancient times they used hollowed out gourds and scooped the aguamiel into large earthenware containers. This agave sap can have a slight alcohol content. Often times fermentation begins in the plant itself, but it is usually insignificant. Cultivators will scrape the inside of this slightly hollowed-out center of the plant to ensure maximum sap production. A normal agave can produce 600 liters of pulque. Modern Mexicans put the aguamiel into huge vats made of oak, fiberglass or plastic called tinas. Where they house the tinas for fermentation is called a tinacal, which is a combination of the Spanish word for vat, tina, with an old Nahuatl word, calli, which Aztecs used as a generic designation for buildings. So, the tinacal is literally “the building of vats.” The pulque producers add seed pulque to the aguamiel in the vats to jump-start the fermentation process. The seed pulque is called semilla in Spanish and xanaxtli in the Aztec language Nahuatl. In modern times both words are used interchangeably. Fermentation may take a week or two and many factors influence the speed and degree of fermentation. These include humidity, temperature and the quality of the agave sap. Pulque doesn’t have a long shelf life and that

Pulque makers use six different types of maguey plants to make this milky-white intoxicating beverage. The maguey, also called agave, is better known to English speakers as the century plant. The plant is a hardy desert-dweller found in the dry mountainous regions of Mexico and in parts of the American Southwest and Texas. Although the century plant only lives to about 30 years, near the end of its life cycle it sends up a characteristic flowering stalk that can reach over 25 feet in height. The Spanish called the plant maguey which comes from the language of the Taino people, the indigenous group the Europeans first encountered in the Caribbean. The Aztecs called the century plant metl. To them, the maguey had many uses. Fibers from its tough spiny leaves were used to make rope or fabric for clothing. The ancient Mexicans used the hard outer membrane of the leaves to make paper. These membranes were also used in cooking. Not leaving much to waste, the thorns of the plant made excellent sewing needles or were used as small tools to make punctures. To make pulque from the agave, cultivators cut off the flower stalk to leave a depressed surface measuring about 12 inches in diameter. It is in this depressed surface where the sap of the agave, called aguamiel, literally “honey water,” collects. Pulque producers gather this sap twice a day and an average plant produces aguamiel throughout a 6-month period before the agave dies. In ancient times they used hollowed out gourds and scooped the aguamiel into large earthenware containers. This agave sap can have a slight alcohol content. Often times fermentation begins in the plant itself, but it is usually insignificant. Cultivators will scrape the inside of this slightly hollowed-out center of the plant to ensure maximum sap production. A normal agave can produce 600 liters of pulque. Modern Mexicans put the aguamiel into huge vats made of oak, fiberglass or plastic called tinas. Where they house the tinas for fermentation is called a tinacal, which is a combination of the Spanish word for vat, tina, with an old Nahuatl word, calli, which Aztecs used as a generic designation for buildings. So, the tinacal is literally “the building of vats.” The pulque producers add seed pulque to the aguamiel in the vats to jump-start the fermentation process. The seed pulque is called semilla in Spanish and xanaxtli in the Aztec language Nahuatl. In modern times both words are used interchangeably. Fermentation may take a week or two and many factors influence the speed and degree of fermentation. These include humidity, temperature and the quality of the agave sap. Pulque doesn’t have a long shelf life and that  is why it is best to consume the beverage soon after the completion of the fermentation process. The drink so often spoils that the very name of the drink, “pulque,” comes from the Aztec phrase octli poliuhqui. This means “spoiled octli” and octli, as previously mentioned, was the Aztec name for pulque. The Spanish conquerors probably didn’t know whether they were drinking a spoiled version or a regular version, or maybe the Aztecs just shared with them the “bad stuff.”

is why it is best to consume the beverage soon after the completion of the fermentation process. The drink so often spoils that the very name of the drink, “pulque,” comes from the Aztec phrase octli poliuhqui. This means “spoiled octli” and octli, as previously mentioned, was the Aztec name for pulque. The Spanish conquerors probably didn’t know whether they were drinking a spoiled version or a regular version, or maybe the Aztecs just shared with them the “bad stuff.”

There are two other beverages that come from the agave plant besides pulque. Many Americans and alcohol lovers worldwide have heard of tequila and mezcal. How are these drinks different from pulque? While pulque is made from fermenting the sap of the century plant found in its cored-out center, tequila and mezcal are made by taking the heart of the plant called the piña, baking it and crushing it to get its juice to ferment. Unlike pulque, tequila and mezcal are distilled spirits and do not spoil. Also, only certain types of maguey plants can produce tequila and mezcal. The blue agave is a favorite for tequila producers.

When the Spanish arrived in central Mexico, not only did they encounter people drinking pulque, they learned of the many stories and ritual practices surrounding this exotic drink. Pulque was usually reserved for the priestly and noble classes of Aztec society, but the elderly and pregnant women were also allowed to drink it whenever they wanted due to its supposed powerful and magical properties. On the sacrificial altars throughout the Aztec Empire, priests and victims of future sacrifices were allowed to imbibe. On certain festival days, officials lifted restrictions on drinking pulque, and the general public indulged in drinking this drink. Anyone throughout the empire caught drinking too much pulque and committing obscene acts of drunkenness was subject to the death penalty. After the Spanish conquest, pulque lost its sacred aspect and became more secular. Large haciendas sprang up to meet the demand of the masses, initially started by the Jesuits sometime in the 17th Century. In colonial Mexico through the early Independence period, local governments and the national one generated a great deal of tax revenues from the sale of this drink. Pulque drinking reaching its peak somewhere in the late 19th Century, slowly replaced by beer and other imported alcohol-based drinks. There has been a slight resurgence of pulque drinking in the early 21st Century.

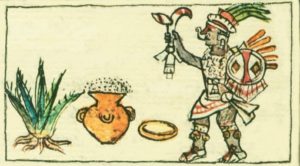

Aficionados who know of its ritual significance often call pulque the “drink of the gods.” Indeed, it is intricately intertwined with the religious beliefs and myths of Mesoamericans dating back thousands of years. Besides the aforementioned mural at the Great Pyramid of Cholula depicting pulque drinkers, some of the earliest representations of pulque drinking in ancient Mexican art come from the city of Teotihuacan. In stone relief carvings dating to about 400 AD at this site, we see masked figures with milky drops falling from their mouths with a background set to maguey leaves. The Zapotecs also had artistic representations of pulque drinking on their monuments dating to about 600 AD. A curious piece of rock art dating to about 900 AD exists near the town of Ixtapantongo in the central Mexican state of México. It features the goddess Mayahuel drinking pulque out of cups in each hand with agave plants all around her. This goddess plays an important role in the story of this popular Mexican drink.

Aficionados who know of its ritual significance often call pulque the “drink of the gods.” Indeed, it is intricately intertwined with the religious beliefs and myths of Mesoamericans dating back thousands of years. Besides the aforementioned mural at the Great Pyramid of Cholula depicting pulque drinkers, some of the earliest representations of pulque drinking in ancient Mexican art come from the city of Teotihuacan. In stone relief carvings dating to about 400 AD at this site, we see masked figures with milky drops falling from their mouths with a background set to maguey leaves. The Zapotecs also had artistic representations of pulque drinking on their monuments dating to about 600 AD. A curious piece of rock art dating to about 900 AD exists near the town of Ixtapantongo in the central Mexican state of México. It features the goddess Mayahuel drinking pulque out of cups in each hand with agave plants all around her. This goddess plays an important role in the story of this popular Mexican drink.

According to the legend, the old Mesoamerican god Quetzalcoatl fell in love with the beautiful goddess Mayahuel and ran away with her. The couple came down out of the skies and planted themselves in the earth after an embrace. They became a tree with two branches, eternally together. Mayahuel’s grandmother did not like this, so she came down to earth with a troop of demons called tzitzimime to try to separate Mayahuel from Quetzalcoatl. The demons ended up shredding Mayahuel to pieces before Mayahuel’s grandmother called them off. Distraught, the god Quetzalcoatl gathered together the pieces of his former love and buried them. At the spot of Mayahuel’s burial grew the first maguey plant. The aguamiel, or sap, from the plant is said to be Mayahuel’s blood which she freely gives to the pulque makers. Mayahuel is said to be the mother of the 400 pulque gods called the Centzon Totochtin. The words centzon totochtin in Nahuatl literally means “400 Rabbits.” It is said that it was a rabbit that first discovered pulque by nibbling on a maguey leaf coated in aguamiel and becoming intoxicated. Researchers debate the function of these 400 pulque gods. They may have been associated with certain towns and specific regions or may have played a role in the ancient Mesoamerican calendar.

In another story of the origins of pulque, it is the opossum, known as the tlacuache to the Aztecs, that discovered the drink. He used his claws to dig into the heart of the agave, drank the aguamiel and became the world’s first drunk. According to Aztec legends, the tlacuache set the course of rivers, and if a river has too many curves and rapids to it, that means the tlacuache had too much pulque to drink on the day he set that river’s course.

For those less inclined to believe that animals had a role in the discovery of pulque, the Aztecs have the story of Xochitl, the beautiful daughter of a minor noble in the Toltec Empire. Xochitl’s father, a wealthy merchant named Papantzin, wanted his daughter to marry the Toltec emperor. He sent Xochitl to the capital city of the Toltecs along with jugs of the sweet maguey sap aguamiel, something altogether new to the Toltec rulers. The emperor was so impressed with the drink that he married Xochitl. One version of the story has Xochitl herself instructing the nobles at the Toltec court on how to process the aguamiel into the finished pulque product. This story may have been used by the Aztecs to justify the special use of pulque among the elite and priestly classes in order to keep it to themselves. According to legend, Xochitl went on to rule the Toltecs after her husband died and was feared throughout ancient Mexico as a powerful warrior-queen. History has so far failed to corroborate any elements of the Xochitl story, and most scholars believe it to be just a legend. As they say, though, many legends do have their bases in fact.

For those less inclined to believe that animals had a role in the discovery of pulque, the Aztecs have the story of Xochitl, the beautiful daughter of a minor noble in the Toltec Empire. Xochitl’s father, a wealthy merchant named Papantzin, wanted his daughter to marry the Toltec emperor. He sent Xochitl to the capital city of the Toltecs along with jugs of the sweet maguey sap aguamiel, something altogether new to the Toltec rulers. The emperor was so impressed with the drink that he married Xochitl. One version of the story has Xochitl herself instructing the nobles at the Toltec court on how to process the aguamiel into the finished pulque product. This story may have been used by the Aztecs to justify the special use of pulque among the elite and priestly classes in order to keep it to themselves. According to legend, Xochitl went on to rule the Toltecs after her husband died and was feared throughout ancient Mexico as a powerful warrior-queen. History has so far failed to corroborate any elements of the Xochitl story, and most scholars believe it to be just a legend. As they say, though, many legends do have their bases in fact.

Aside from the tale involving the beautiful goddess Mayahuel, the Aztecs have another story about Quetzalcoatl and pulque. For more information about this ancient Mesoamerican god, please see Mexico Unexplained episode number one hundred: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sGEQZysH0vo In this story, Quetzalcoatl the god and ruler of Tula drinks too much pulque one night during a festival and shames himself, committing unspeakable acts. In the morning, realizing what he has done, he flees the country, abandoning his kingdom in disgrace. The story serves two purposes: It explains why Quetzalcoatl fled Tula and it illustrates what bad things can result from too much pulque consumption.

Many stories about this magical drink are simply not known. What did the Huastecs believe or even the Maya? Pulque has been around for almost two thousand years, but very little information exists about it outside of the Aztec world and their immediate past. Perhaps these other civilizations had their share of lively pulque stories and legends that are now lost in a somewhat drunken haze of history.

REFERENCES

Ancient History Encyclopedia website, the Archaeology wiki website, various other web-based sources.