Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

In May of 1835, the citizens of Mexico City bought lots of newspapers to keep up with the perilous current events in Mexico’s northern provinces. For many months what the papers called indios bárbaros, or “Barbarian Indians” in English, had been conducting raids on ranches and towns in the north, with the state of Chihuahua the hardest hit. That May, 800 Comanche warriors laid waste to one of the region’s most sprawling ranchos, the Hacienda de las Animas, burning everything in sight including houses and stores of corn and beans. When the Comanches withdrew from eastern Chihuahua they had killed 6 men at the hacienda and took 39 women and children captive. Along with hundreds of horses and cattle, they took the captives with them on the long trek across the Rio Grande and into the heart of what the Spanish and Mexicans had called “La Comanchería,” the homeland of the Comanches in the southern Great Plains in what is now the US states of Texas, New Mexico, Oklahoma and Kansas. The Comanches knew that no organized force of Mexicans would follow them as they had been doing this sort of thing for decades, although not this intense. While the nation of Mexico would shiver at the thought of the Comanche raids of the spring of 1835, the worst was yet to come. Why was this happening and what events led up to that disastrous raid of the Hacienda de las Animas?

In May of 1835, the citizens of Mexico City bought lots of newspapers to keep up with the perilous current events in Mexico’s northern provinces. For many months what the papers called indios bárbaros, or “Barbarian Indians” in English, had been conducting raids on ranches and towns in the north, with the state of Chihuahua the hardest hit. That May, 800 Comanche warriors laid waste to one of the region’s most sprawling ranchos, the Hacienda de las Animas, burning everything in sight including houses and stores of corn and beans. When the Comanches withdrew from eastern Chihuahua they had killed 6 men at the hacienda and took 39 women and children captive. Along with hundreds of horses and cattle, they took the captives with them on the long trek across the Rio Grande and into the heart of what the Spanish and Mexicans had called “La Comanchería,” the homeland of the Comanches in the southern Great Plains in what is now the US states of Texas, New Mexico, Oklahoma and Kansas. The Comanches knew that no organized force of Mexicans would follow them as they had been doing this sort of thing for decades, although not this intense. While the nation of Mexico would shiver at the thought of the Comanche raids of the spring of 1835, the worst was yet to come. Why was this happening and what events led up to that disastrous raid of the Hacienda de las Animas?

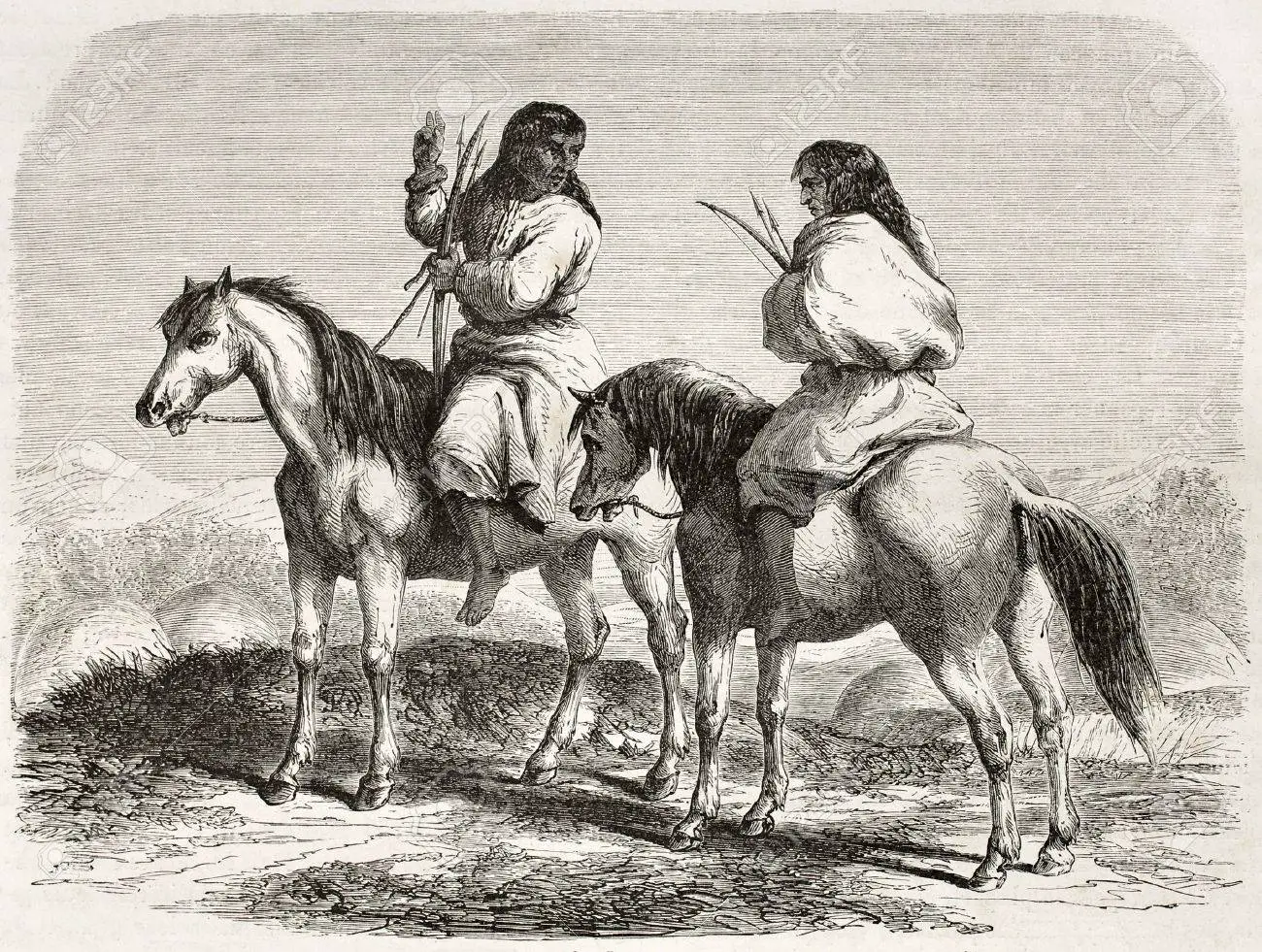

The word “Comanche” was first used in 1706 when a group of southern plains people threatened to attack the pueblos in what is now southern Colorado. The Ute people called them kamantsi, which meant in their language, “Enemy People.” The Spanish started calling these plains people “Comanche,” which replaced their generic term of “Norteño,” or “Northerner.” The Comanches at one time called themselves the Newe and were part of the Shoshone cultural and linguistic group. After the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 and the release of Spanish horses onto the plains, the Comanches became a distinct people known for their horse-riding abilities, although still very much linked to their northern cousins, the Shoshone. With the use of the horse the Comanches expanded their territory. On old Spanish maps the area comprising the southern plains of the modern United States is often labeled La Comanchería or “The Land of the Comanches.” The Spanish had their first real confrontation with the Comanches in 1758. The previous year the Lipan Apaches suggested the Spanish build a mission to convert the Apache people to Christianity and suggested a location for the mission. The Spanish didn’t realize that this was a trick and the Apaches’ suggested location was deep in Comanche territory. When the Spanish built the Mission of Santa Cruz de San Sabá and the adjacent Presidio San Luis de las Amarillas, they did not realize they were far north of Apache territory and on lands claimed by the Comanches. The trick worked and the Comanches attacked the mission and presidio, killing everyone and destroying everything. The Spanish knew to stay out of the area of what is now central Texas.

The word “Comanche” was first used in 1706 when a group of southern plains people threatened to attack the pueblos in what is now southern Colorado. The Ute people called them kamantsi, which meant in their language, “Enemy People.” The Spanish started calling these plains people “Comanche,” which replaced their generic term of “Norteño,” or “Northerner.” The Comanches at one time called themselves the Newe and were part of the Shoshone cultural and linguistic group. After the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 and the release of Spanish horses onto the plains, the Comanches became a distinct people known for their horse-riding abilities, although still very much linked to their northern cousins, the Shoshone. With the use of the horse the Comanches expanded their territory. On old Spanish maps the area comprising the southern plains of the modern United States is often labeled La Comanchería or “The Land of the Comanches.” The Spanish had their first real confrontation with the Comanches in 1758. The previous year the Lipan Apaches suggested the Spanish build a mission to convert the Apache people to Christianity and suggested a location for the mission. The Spanish didn’t realize that this was a trick and the Apaches’ suggested location was deep in Comanche territory. When the Spanish built the Mission of Santa Cruz de San Sabá and the adjacent Presidio San Luis de las Amarillas, they did not realize they were far north of Apache territory and on lands claimed by the Comanches. The trick worked and the Comanches attacked the mission and presidio, killing everyone and destroying everything. The Spanish knew to stay out of the area of what is now central Texas.

The Spanish settlers in New Mexico and Texas in the 1700s and early 1800s lived with the Comanches in a sort of peaceful coexistence on the fringes of Comanche territory. The nomadic Comanches would often go into the Spanish settlements to trade. Comanches mostly would trade finished buffalo hides for weapons, textiles, tools and food. The trading relationship was mutually beneficial and somewhat peaceable relations existed between the two peoples. In some instances, though, where there were small Comanche raids for livestock or threats of escalated hostility, Spanish authorities paid tribute to Comanche leaders, buying them off, so to speak, to ensure the peace was maintained.

This changed somewhat when Mexico officially gained its independence from Spain in 1821. A highly centralized government in Mexico City was short on cash and paid little attention to the northern frontier. Local Mexican officials in the territories of New Mexico and Texas had to deal with the threats from hostile Comanches on their own. They often did not have the manpower or the firepower to fend off Comanche raiding parties. Ranch and hacienda owners were left to fend for themselves.

This changed somewhat when Mexico officially gained its independence from Spain in 1821. A highly centralized government in Mexico City was short on cash and paid little attention to the northern frontier. Local Mexican officials in the territories of New Mexico and Texas had to deal with the threats from hostile Comanches on their own. They often did not have the manpower or the firepower to fend off Comanche raiding parties. Ranch and hacienda owners were left to fend for themselves.

By the mid-1820s the Comanches began crossing the Rio Grand more frequently, at first to attack their old enemies, the Lipan Apache, but then to prey on Mexican settlements. In 1826, in response to the increasing intensity of Comanche raids, the government of Nuevo Leon issued a proclamation stating that if any Mexican citizens were to travel in the countryside they were to be in parties of no less than 30 men, and all were to be armed and mounted on horseback. Some northern Mexican states and local governments even offered up to 100 pesos bounty for a Comanche scalp.

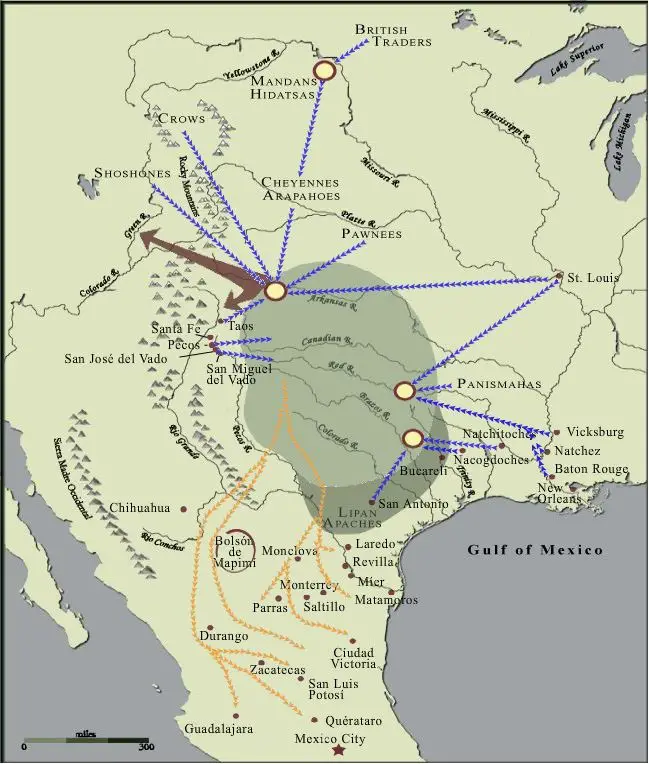

Why did these southern raids become more intense in the 1820s and 1830s? The Comanches experienced pressure and competition for resources in the Comanchería. American traders north of the Arkansas River set up outposts but traded with the northern Plains peoples – specifically the Southern Cheyenne and the Arapaho – the enemies of the Comanches. The Comanches were relegated to trade with the communities of the northern edge of the Republic of Mexico which had become more impoverished since independence. Also at this time, the Americans began relocating eastern Indians via the Trail of Tears into what is now Oklahoma. Then, eastern Oklahoma was part of traditional Comanche territory. Those relocated Indians went beyond eastern Oklahoma and began competing for resources in other parts of the southern Plains. By 1836, the Comanches also had to deal with the new Republic of Texas which claimed a big chunk of the Comanchería and saw increasing settlements by the Anglo-American Texans. The Comanches felt a little squeezed out of their traditional homeland and set their sights south of the Rio Grande.

Before 1840, Comanche expeditions across the Rio Grande consisted of small excursions of a few dozen raiders not too deep into Mexico, to capture livestock and occasionally take captives. Between September of 1840 and March of 1841, northern Mexico saw what historians call the “Great Raids” of the Comanches. The Comanche raiding parties consisted of anywhere from 200 to 800 men and there were 6 separate raids during this time going deep into Mexican territory. One raid even went as far as 400 miles south of the Rio Grande. During the period of the “Great Raids,” 472 Mexicans were reported killed and over 100 captives were taken back to the Comanchería. Many ranches and haciendas were destroyed. Hundreds of Mexicans were left homeless or without livelihoods in the wake of the Comanche destruction.

The Mexicans could do little to mount an effective counterattack or to take the war to Comanche territory. Southern Plains historian Brian Delay, in one of his articles of this time period gives a good explanation as to why going to the Comanchería to fight the raiders on their home turf was a bad idea. The author states:

The Mexicans could do little to mount an effective counterattack or to take the war to Comanche territory. Southern Plains historian Brian Delay, in one of his articles of this time period gives a good explanation as to why going to the Comanchería to fight the raiders on their home turf was a bad idea. The author states:

“Mexicans trying to organize campaigns into la comanchería faced daunting challenges. An effective force would have to be large and organizers would find men reluctant to participate unless their families and property could be protected in their absence. A large force of Mexicans would likely find insufficient meat on the plains, and so, if they planned on being out for any length of time, would have to march with slow-moving cattle in tow. Water and pasturage for cattle and, especially for large numbers of horses, would be reliable only during certain times of the year. Strategists also worried about Comanche herds drinking waterholes dry before Mexicans got there, or else finding water sources poisoned, infested with dead horses killed intentionally by the Comanches. Finally, Southern Plains families ranged seasonally over a huge territory and the Mexicans themselves had seasonal peaks to their labor cycle, so it took tremendous resources, political capital, administrative skill, and, not least, luck, to coordinate and mobilize effective campaigns.”

There was also another complication. Mexicans would also have to cross over into the territory of the Republic of Texas to get to the Comanche homeland, and Mexico did not recognize Texas as an independent, sovereign nation. The independent Texans would not have taken too kindly to a massive Mexican expeditionary force crossing their territory to take out the Comanches.

By the middle of the 1840s parts of northern Mexico looked like permanent disaster areas. The Comanche raids had become even more intense and had gone deeper into Mexico by this time. One Mexico City newspaper claimed that one day soon there would be Comanche war parties riding through the streets of the Mexican capital. This was on the heels of a report of 200 Comanche warriors parading through downtown Durango on horseback unchallenged. By 1848, the Comanches had conducted a total of 44 raids consisting of over 100 men each. There were 2,649 dead victims of these raids and 852 captives, of whom 580 were repatriated back to Mexico. The remaining captives served as slaves to the Comanches and never left the Comanchería. The number of livestock stolen and brought across the Rio Grande amounted to well over 100,000. What livestock the Comanches could not take away, they killed. The Comanches suffered over 700 dead and over 30 were taken prisoner in Mexico. The Comanches also succumbed to various diseases brought back to their homeland by Mexican captives. According to one Mexican historian, during the 1840s the worst raiding year was from July of 1845 to June of 1846. 652 Mexicans and 48 Comanches were killed, and up to 10,000 animals were either stolen or killed. Many Mexicans in the north had to abandon their haciendas and ranchos or leave their smoldering small towns behind.

Journeying through northern Mexico in 1846, British travel writer George Ruxton would say this about the area in his book, Adventures in Mexico and the Rocky Mountains:

“They [the Comanche] are now overrunning the whole departments of Durango and Chihuahua, have cut off all communication, and defeated…the regular troops sent against them. Upwards of ten thousand head of horses and mules have already been carried off, and scarcely has a hacienda or rancho on the frontier been unvisited, and everywhere the people have been killed or captured. The roads are impassible, all traffic is stopped, the ranchos barricaded, and the inhabitants afraid to venture out of their doors.”

Another travel writer, American Josiah Gregg, had something similar to say when he visited northern Mexico in 1847:

Another travel writer, American Josiah Gregg, had something similar to say when he visited northern Mexico in 1847:

“The whole country from New Mexico to the borders of Durango is almost entirely depopulated. The haciendas and ranchos have been mostly abandoned, and the people chiefly confined to the towns and cities.”

The situation with the Comanches changed again during the Mexican War of 1846-1848. When American troops invaded northern Mexico, they found a dejected and dispirited population inhabiting a devastated landscape. In addition to telling the people of northern Mexico that the Americans “wish to see you liberated from despots,” US General Zachary Taylor promised, “to drive back the savage Comanches, to prevent the renewal of their assaults, and to compel them to restore to you from captivity your long lost wives and children.”

After the dust settled from the Mexican War, the treaty that gave half of Mexico’s territory to the United States also had a section to address General Taylor’s promise. Article XI of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo compels the United States to end Comanche incursions into Mexican territory. Did the Americans live up to the treaty? The Comanche raids were curtailed with the US takeover of what is now the American Southwest, but they did not completely stop. History records 366 claims made against the United States by Mexicans seeking compensation under Article XI of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. As the Great Plains started sprouting fences and farms popped up on the prairies, the nomadic days of the Comanches slowly came to an end. Immediately after the American Civil War, the Comanches were relocated onto permanent reservations in Oklahoma and Texas. The last Comanche raid into Mexico occurred in 1870 when a few dozen raiders killed some 30 Mexicans on a hacienda outside of Lampazos de Naranjo, Nuevo Leon, just 70 miles across the Rio Grande. A 50-year war effectively ended when there were no more Comanches able to conduct raids. By the early 1870s, reduced by disease and demoralization, the Comanches only numbered about 1,500 people and were now sedentary, their culture crushed.

REFERENCES

Adams, David B. “Embattled Borderland: Northern Nuevo León and the Indios Bárbaros, 1686–1870” The Southwestern Historical Quarterly, Vol 95, No. 2 (Oct 1991), pp. 205–220

Delay, Brian. “The Wider World of the Handsome Man: Southern Plains Indians Invade Mexico, 1830-1848.” Journal of the Early Republic 27, no. 1 (2007): 83-113.

Smith, Ralph A. “The Comanche Bridge between Oklahoma and Mexico, 1843–1844.” The Chronicles of Oklahoma, Vol 39, No. 1, 1961