Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

It was 11:00 in the morning on Thursday, October 19, 1854. A man named William Walker was on trial in San Francisco for violating The Neutrality Act, a law first envisioned by President George Washington in 1793, passed by Congress in 1794, and later superseded by a revised act in 1817. The act declares in part:

It was 11:00 in the morning on Thursday, October 19, 1854. A man named William Walker was on trial in San Francisco for violating The Neutrality Act, a law first envisioned by President George Washington in 1793, passed by Congress in 1794, and later superseded by a revised act in 1817. The act declares in part:

“If any person shall within the territory or jurisdiction of the United States begin or set on foot or provide or prepare the means for any military expedition or enterprise…against the territory or dominions of any foreign prince or state of whom the United States was at peace that person would be guilty of a misdemeanor.”

Walker was facing up to three years in prison and a three thousand dollar fine for his ill-fated invasion of Mexican territory in an attempt to set up a new nation in northern Mexico called The Republic of Lower California. Walker’s trial lasted for several days and the citizens of San Francisco waited anxiously for the latest edition of the Daily Alta California newspaper to read about the trial. The trial complete, the October 20th edition of the paper heralded the news:

“The jury were out exactly eight minutes. They then came into Court and rendered a verdict of Not Guilty. When the verdict was pronounced, which the foreman did in a very emphatic tone, there was an audible manifestation of applause outside the bar, and many came up to shake Mr. Walker by the hand and congratulate him.”

William Walker was only 30 years old at the time of the trial but had already lived a long and colorful life. Born in Nashville, Tennessee in 1824, he was the grandson of Lipscomb Norvell, a Revolutionary War officer from Virginia. Described as a bright and well-mannered child, Walker graduated summa cum laude from the University of Nashville at the age of fourteen. After getting his diploma he spent time traveling in Europe and studied medicine at the University of Edinburgh and the University of Heidelberg before returning to the US to finish off his medical degree at the University of Pennsylvania at the age of 19. Walker practiced medicine for a few years in Philadelphia before moving to New Orleans. While in Louisiana he studied law, practiced for a while and then became an owner and editor of the local newspaper The New Orleans Crescent. Like so many other young American men at the time, Walker looked west and sought his fortune in California, arriving in San Francisco in 1849 at the height of the Gold Rush. Walker did not mine gold but worked for the fledgling newspaper The Daily Herald as a writer and editor. After an injury in a duel in 1851, Walker joined forces with a man named Henry P. Watkins and opened a law practice in Marysville.

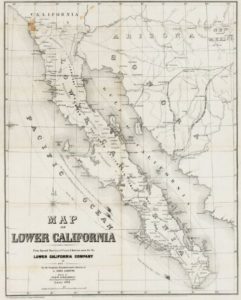

With superior ability comes superior ambition. The doctor-journalist-lawyer turned his attention to Latin America where he saw promises and opportunities now exhausted in California. Walker was taken by the idea of what was termed “filibustering.” Now meaning a long, drawn-out speech in front of a legislature, in the 1800s filibuster had a different meaning. A “filibuster” was a person who engaged in “filibustering,” or the act of invading a foreign country with intent to take it over without the formal backing of the US government. Walker had his sights set on northern Mexico which had been sparsely populated before the California Gold Rush and less so after. The regions of Sonora and the Baja Peninsula seemed ripe for the picking for an ambitious, well-backed gringo to come in and set up his own private realm.

William Walker decided to test the waters first and teamed up with his law partner Henry Watkins to make an investigative journey to the port of Guaymas on the northern coast of Sonora. This was June of 1853. His idea was to arrive at the port and seek an audience with the governor. Walker’s outwardly-facing plan was to propose an American colony in northern Sonora to protect the frontier from Apache raids in exchange for vast tracts of land. Before leaving San Francisco, however, Walker floated bonds for the “Republic of Sonora” to finance a future expedition of conquest, promising bond holders repayment through the first proceeds of the new government. Walker and Watkins obtained passports in San Francisco from the Mexican consul there who had not heard of the bond scheme. The consul was very suspicious of Walker’s intentions, nonetheless, and sent word ahead to the Sonoran governor to warn him of Walker’s imminent arrival. When Walker and Watkins arrived at Guaymas, the port authorities refused to countersign their passports and they were denied travel within the state of Sonora. While in Guaymas, Walker would later claim, he heard testimony from Mexican residents indicating that they would welcome gringo rule as they had been neglected by federal authorities in faraway Mexico City and had been plagued for years by marauding Indians and bandits. Walker encountered another American who was living in Guaymas at the time, a man named T. Robinson Warren. In his diary, Warren wrote this about Walker:

William Walker decided to test the waters first and teamed up with his law partner Henry Watkins to make an investigative journey to the port of Guaymas on the northern coast of Sonora. This was June of 1853. His idea was to arrive at the port and seek an audience with the governor. Walker’s outwardly-facing plan was to propose an American colony in northern Sonora to protect the frontier from Apache raids in exchange for vast tracts of land. Before leaving San Francisco, however, Walker floated bonds for the “Republic of Sonora” to finance a future expedition of conquest, promising bond holders repayment through the first proceeds of the new government. Walker and Watkins obtained passports in San Francisco from the Mexican consul there who had not heard of the bond scheme. The consul was very suspicious of Walker’s intentions, nonetheless, and sent word ahead to the Sonoran governor to warn him of Walker’s imminent arrival. When Walker and Watkins arrived at Guaymas, the port authorities refused to countersign their passports and they were denied travel within the state of Sonora. While in Guaymas, Walker would later claim, he heard testimony from Mexican residents indicating that they would welcome gringo rule as they had been neglected by federal authorities in faraway Mexico City and had been plagued for years by marauding Indians and bandits. Walker encountered another American who was living in Guaymas at the time, a man named T. Robinson Warren. In his diary, Warren wrote this about Walker:

“His appearance was that of anything else than a military chieftain. Below the medium height, and very slim, I should hardly imagine him to weigh over a hundred pounds. His hair light and towy, while his almost-white eyebrows and lashes concealed a seemingly pupil-less, grey, cold eye, and his face was a mass of yellow freckles, the whole expression very heavy. His dress was scarcely less remarkable than his person. His head was surmounted by a huge white fur hat, whose long knap waved with the breeze, which, together with a very ill-made short-waisted blue coat, with gilt buttons, and a pair of grey, strapless pantaloons, made up the ensemble of as unprepossessing-looking a person as one would meet in a day’s walk. I will leave you to imagine the figure he cut in Guaymas with the thermometer at 100 degrees when everyone else was arrayed in white. Indeed, half the dread which the Mexicans had of filibusters vanished when they saw this their Grand Sachem, —such an insignificant-looking specimen. But anyone who estimated Mr. Walker by his personal appearance, made a great mistake. Extremely taciturn, he would sit for an hour in company without opening his lips; but once interested, he arrested your attention with the first word he uttered, and as he proceeded, you felt convinced that he was no ordinary person. To a few confidential friends he was most enthusiastic upon the subject of his darling project, but outside of those immediately interested, he never mentioned the topic.”

Without the formal blessing from the government of Sonora to start a colony, Walker decided to continue with his plan to create his own personal empire in northern Mexico. He started a silent PR campaign in San Francisco to drum up interest in his next adventure. With the Gold Rush effectively over and done with by 1853, California harbored many idle men who were attracted to the area from faraway places by the possibility of riches and adventure. Walker tapped into this and thus had ample volunteers to join his expeditionary force. His next task was to gather together a ship, provisions and arms. In the meantime, he told Mexican general José Castro that a force of 2,000 well-funded and amply-supplied Americans would be arriving in Sonora sometime in September, half on foot and half by sea, with a rendezvous point somewhere between Guaymas and the mouth of the Colorado River. Walker promised the general vast amounts of land and also swore to divide the land of the province among Mexican families already living in Sonora. Sonora would declare its independence and then be asked to be admitted to the United States, much as Texas did. Walker hoped that his proposals to General Castro would generate support among Sonora’s current residents and make his takeover of northern Mexico much easier. The Mexican general did not support Walker’s scheme but told no one and did nothing to stop it.

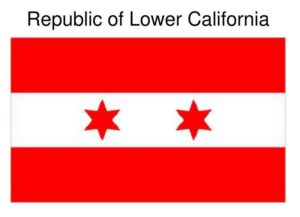

Before leaving California, Walker ran into problems with governmental authorities. The commander of the Pacific Division of the United States Army, Ethan Allen Hitchcock, heard of Walker’s plans and seized his ship, called the Arrow, which had already been fully stocked with arms and supplies. Instead of waiting for his claim against the seizure to be processed through the courts, Walker chartered another boat, the Caroline, and at around 1:00 in the morning on October 17, 1853, he slipped out of San Francisco Harbor with 45 men bound for Sonora. Unknowingly, Walker’s hasty departure would cripple his entire expedition. With one fourth the men and sailing with less than adequate supplies, Walker knew that he could never take over the port of Guaymas. He changed his plans and decided to make the southern tip of the Baja Peninsula his base of operations. On October 28 the Caroline landed at Cabo San Lucas, stayed in port to requisition supplies and in a few days left for La Paz, sailing under the Mexican flag. Walker entered La Paz on November 3rd and within two hours captured the city and the governor of the Baja California Territory, Colonel Rafael Espinosa. Walker’s men quickly took down the Mexican flag and hoisted the red and white flag of the “new republic.” Walker was quick to proclaim, “The Republic of Lower California is hereby declared Free, Sovereign and Independent and all Allegiance to the Republic of Mexico is forever renounced.” Wasting no time, Walker organized a government and cabinet departments. He also declared that the Napoleonic code in force in Louisiana would be the law of the land for the new republic. Walker decided to leave La Paz for Cabo San Lucas to establish his new capital there, but not after local residents grabbed all manner of firearms and took potshots at Walker and his men. From rooftops and from the safety of adobe alleyways, the Mexican citizens of La Paz did what they could to disrupt the invading gringos. Walker’s solution was to order the bombardment of La Paz and sent a force of 30 men into town to take care of the pockets of guerrilla resistance. In the meantime, the new governor of the Baja California Territory sent by Mexico City arrived at La Paz to relieve the existing governor, Colonel Espinosa, whose term was ending. Walker captured the new governor, Colonel Juan Rebolledo, and held him hostage. When the fighting ended in La Paz, Walker’s forces returned to Cabo San Lucas.

Before leaving California, Walker ran into problems with governmental authorities. The commander of the Pacific Division of the United States Army, Ethan Allen Hitchcock, heard of Walker’s plans and seized his ship, called the Arrow, which had already been fully stocked with arms and supplies. Instead of waiting for his claim against the seizure to be processed through the courts, Walker chartered another boat, the Caroline, and at around 1:00 in the morning on October 17, 1853, he slipped out of San Francisco Harbor with 45 men bound for Sonora. Unknowingly, Walker’s hasty departure would cripple his entire expedition. With one fourth the men and sailing with less than adequate supplies, Walker knew that he could never take over the port of Guaymas. He changed his plans and decided to make the southern tip of the Baja Peninsula his base of operations. On October 28 the Caroline landed at Cabo San Lucas, stayed in port to requisition supplies and in a few days left for La Paz, sailing under the Mexican flag. Walker entered La Paz on November 3rd and within two hours captured the city and the governor of the Baja California Territory, Colonel Rafael Espinosa. Walker’s men quickly took down the Mexican flag and hoisted the red and white flag of the “new republic.” Walker was quick to proclaim, “The Republic of Lower California is hereby declared Free, Sovereign and Independent and all Allegiance to the Republic of Mexico is forever renounced.” Wasting no time, Walker organized a government and cabinet departments. He also declared that the Napoleonic code in force in Louisiana would be the law of the land for the new republic. Walker decided to leave La Paz for Cabo San Lucas to establish his new capital there, but not after local residents grabbed all manner of firearms and took potshots at Walker and his men. From rooftops and from the safety of adobe alleyways, the Mexican citizens of La Paz did what they could to disrupt the invading gringos. Walker’s solution was to order the bombardment of La Paz and sent a force of 30 men into town to take care of the pockets of guerrilla resistance. In the meantime, the new governor of the Baja California Territory sent by Mexico City arrived at La Paz to relieve the existing governor, Colonel Espinosa, whose term was ending. Walker captured the new governor, Colonel Juan Rebolledo, and held him hostage. When the fighting ended in La Paz, Walker’s forces returned to Cabo San Lucas.

Upon seeing a large Mexican naval vessel in the harbor at Cabo, Walker decided to sail around the peninsula and make his capital city at Ensenada. He arrived at the port on November 29, 1853 and issued a series of proclamations. One was to the people of the United States to give some justification for his actions. Another was to the people of the former Baja California Territory, assuring them that their rights, lives and property would be guaranteed provided they swore allegiance to the new nation. When the proclamations along with the news of the Battle of La Paz reached San Francisco, so great was the excitement for Walker’s adventure that the white and red flag of the Republic of Lower California was hoisted over a building on the corner of Kearney and Sacramento Streets which served as a makeshift recruiting center for the army of the new republic. In the first few days over 200 men signed up. They were of little help to Walker who was facing ground battles between local Mexican citizens who had teamed up with bandits to resist the gringos. Even in the face of losing men and dwindling ammunition, Walker continued undaunted. He gathered 20 of his bravest men, led by an Irish teenager named Timothy Crocker, and charged the Mexican position, causing the ragtag force to retreat. This was good news for Walker and his men, but they were left without a ship. During the battle, the two hostages, the two former Mexican governors of the territory, had convinced the captain of the Caroline of the futility of the  Walker enterprise and promised him a reward to take them back to Cabo San Lucas. The ship captain was sure of the expedition’s failure and the governors’ offer seemed better to him than staying behind with William Walker. Watching his ship sail off in the distance and still very battle weary, Walker regrouped and reorganized. He even changed the name of his new capital from Ensenada to Fort McKibben to honor one of his fallen officers. By December 28th 250 men arrived at Fort McKibben by ship but hearing of Walker’s success they brought only guns and ammunition, no food. Walker then ordered the takeover of the nearby town of Santo Tomás to capture cattle and gather other supplies. Once done, Walker ordered an overland march to Guaymas through some of the most desolate territory in all of Mexico. It took two weeks for them to reach the Colorado River, at which time was too wide and to deep to cross with ease. Walker had his men build rafts. It was at this time that many of his men deserted and crossed the US border to try to make it north to Fort Yuma. Arriving in Sonora with a skeleton force, Walker decided to return to Fort McKibben to give up on the conquest of Sonora and just hold the Baja Peninsula. All along the journey, the group was harassed by Cocopah Indians and a contingent of bandits led by a man named Guadalupe Melendrez, who wanted the expeditionary force’s cattle and guns. The filibuster army retreated but by the time they got to the Pacific coast of Baja the men were dejected, hungry, thirsty and so worn out that Walker made the decision to march north to San Diego and surrender to the American authorities. The last major battle for the Republic of Lower California occurred in sight of the US border between Walker’s forces and the bandit, Melendrez. Melendrez said he would grant Walker safe passage to San Diego if he gave up his arms and remaining supplies. Walker didn’t trust him and led the charge with his remaining thirty men to break the Mexican line and make a run for the border. Walker was successful and ultimately made it to San Diego with his remaining men and surrendered to federal authorities.

Walker enterprise and promised him a reward to take them back to Cabo San Lucas. The ship captain was sure of the expedition’s failure and the governors’ offer seemed better to him than staying behind with William Walker. Watching his ship sail off in the distance and still very battle weary, Walker regrouped and reorganized. He even changed the name of his new capital from Ensenada to Fort McKibben to honor one of his fallen officers. By December 28th 250 men arrived at Fort McKibben by ship but hearing of Walker’s success they brought only guns and ammunition, no food. Walker then ordered the takeover of the nearby town of Santo Tomás to capture cattle and gather other supplies. Once done, Walker ordered an overland march to Guaymas through some of the most desolate territory in all of Mexico. It took two weeks for them to reach the Colorado River, at which time was too wide and to deep to cross with ease. Walker had his men build rafts. It was at this time that many of his men deserted and crossed the US border to try to make it north to Fort Yuma. Arriving in Sonora with a skeleton force, Walker decided to return to Fort McKibben to give up on the conquest of Sonora and just hold the Baja Peninsula. All along the journey, the group was harassed by Cocopah Indians and a contingent of bandits led by a man named Guadalupe Melendrez, who wanted the expeditionary force’s cattle and guns. The filibuster army retreated but by the time they got to the Pacific coast of Baja the men were dejected, hungry, thirsty and so worn out that Walker made the decision to march north to San Diego and surrender to the American authorities. The last major battle for the Republic of Lower California occurred in sight of the US border between Walker’s forces and the bandit, Melendrez. Melendrez said he would grant Walker safe passage to San Diego if he gave up his arms and remaining supplies. Walker didn’t trust him and led the charge with his remaining thirty men to break the Mexican line and make a run for the border. Walker was successful and ultimately made it to San Diego with his remaining men and surrendered to federal authorities.

The story of the Republic of Lower California has an interesting epilogue. The Mexican government decided to recognize the contributions of the band of bandits led by Guadalupe Melendrez and reward them for the instrumental role they played in ending the Walker plan for an independent Baja California. They made Melendrez the military commander of the border area and rewarded his men with gold and plots of land. Melendrez was later executed by hanging by the Mexican authorities after word reached Mexico City that he was planning on selling off the entire northern border area to the United States for two million dollars. As mentioned earlier, Walker was tried and acquitted of all wrongdoing in a US court after 8 minutes of jury deliberations. Walker saw the Republic of Lower California as a warm-up for greater future projects. His filibustering career not over, he would later try his hand at conquest in Central America where he would ultimately meet his end by firing squad on September 12, 1860 at the age of 36 in Trujillo, Honduras. Unknown to many now, the Walker plan for the Republic of Lower California had huge international repercussions. During Walker’s exploits, the United States, represented by US Ambassador to Mexico James Gadsden, was negotiating with the Santa Ana government in Mexico City to acquire additional territory to build a railroad through what is now southern Arizona and New Mexico. The Americans eventually paid the cash-strapped Santa Ana government $10 million for this patch of desert later called The Gadsden Purchase. Had it not been for the nuisance Walker caused and the vulnerability Santa Ana felt because of the Walker fiasco, perhaps the Mexican government would have been willing to sell off more territory to the United States. In January 1854, Ambassador Gadsden told a reporter at the Charleston Daily Courier that, “had not the insane expedition caused Santa Ana to set his face resolutely against it, further negotiations would have added Lower California to the United States.” It seems as if the Baja California peninsula was saved from being an extension of US-owned southern California by the actions and ambitions of one lone man and his followers. We will leave it to the alternative history folks to come up with an ending had Walker never tried to enact such a scheme.

REFERENCES

Owens, Bob. “The Saga of William Walker.” San Diego Reader, 18 Jun 1987.

“Trial of Wm. Walker for Fillibustering.” Daily Alta California. 10 Oct 1854. Vol. 5, no. 291, p. 2.

Vore, Jimmie Dean. Early Filibustering in Sonora and Baja California, 1848-1854. Alva, Oklahoma: Northwestern State College, 1966.