Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

The date was April 8, 1566. In the northern fringes of New Spain, a small band of miners was traveling from the Gulf port of Veracruz to the frontier town of Durango delivering supplies. They were caught in a rainstorm and had to stop and make camp in the rugged hills outside the modern-day Mexican city of Fresnillo, Zacatecas. In their wagon of provisions was a large wooden crucifix intended for a new church in Durango. The men wanted to strike it rich in the newly discovered silver mines in the region, so they took the crucifix out of its large box and prayed to it, hoping that God would reward them for their veneration and piousness. That night it continued to rain heavily, and when the men woke up the next day, they saw a newly revealed vein of silver on the side of a cliff. The little caravan never made it to Durango. The men stopped there, made a more permanent camp, and established their own silver mine. They discovered the vein on April 9, the feast day of Saint Dimitri, an early Christian martyr killed by the Roman Emperor Diocletian. Because of their good fortune, they decided to name their town San Demetrio. The men cherished that large church crucifix that they felt was responsible for their newly found riches and built a small chapel around it. The local indigenous population, the mountain-dwelling Huichol people who had only partially converted to Christianity, seemed to be drawn to the Christ. Rumors circulated throughout the area that the Cristo had special healing powers and emitted a distinct positive energy. It only took a few decades before the little chapel became a pilgrimage site for Spanish and Native alike. The people of the region nicknamed the crucifix, El Señor de los Plateros, or in English, the Lord of the Silver Miners. Over the years the people in charge of the chapel added silver overlay to the Christ figure and other embellishments, making a more elaborate presentation to visitors who started to come from all over colonial Mexico. In 1621, the town even changed its name from San Demetrio to Plateros to pay homage to the important shrine. In the 1780s, the town began construction on a more impressive stone church to replace the smaller chapel that had been in use for some 200 years.

The date was April 8, 1566. In the northern fringes of New Spain, a small band of miners was traveling from the Gulf port of Veracruz to the frontier town of Durango delivering supplies. They were caught in a rainstorm and had to stop and make camp in the rugged hills outside the modern-day Mexican city of Fresnillo, Zacatecas. In their wagon of provisions was a large wooden crucifix intended for a new church in Durango. The men wanted to strike it rich in the newly discovered silver mines in the region, so they took the crucifix out of its large box and prayed to it, hoping that God would reward them for their veneration and piousness. That night it continued to rain heavily, and when the men woke up the next day, they saw a newly revealed vein of silver on the side of a cliff. The little caravan never made it to Durango. The men stopped there, made a more permanent camp, and established their own silver mine. They discovered the vein on April 9, the feast day of Saint Dimitri, an early Christian martyr killed by the Roman Emperor Diocletian. Because of their good fortune, they decided to name their town San Demetrio. The men cherished that large church crucifix that they felt was responsible for their newly found riches and built a small chapel around it. The local indigenous population, the mountain-dwelling Huichol people who had only partially converted to Christianity, seemed to be drawn to the Christ. Rumors circulated throughout the area that the Cristo had special healing powers and emitted a distinct positive energy. It only took a few decades before the little chapel became a pilgrimage site for Spanish and Native alike. The people of the region nicknamed the crucifix, El Señor de los Plateros, or in English, the Lord of the Silver Miners. Over the years the people in charge of the chapel added silver overlay to the Christ figure and other embellishments, making a more elaborate presentation to visitors who started to come from all over colonial Mexico. In 1621, the town even changed its name from San Demetrio to Plateros to pay homage to the important shrine. In the 1780s, the town began construction on a more impressive stone church to replace the smaller chapel that had been in use for some 200 years.

Although this is the official story told in modern-day brochures and on the official Plateros web site, there are two different oral histories of the miraculous Christ of Plateros. In one version of the story, the Christ carving was being transported overland on the back of a mule, part of a supply transport for a wealthy hacienda. The large crucifix had been specially made in Spain for use in the hacienda’s private chapel. The mule carrying the cross somehow made its way into a small house of a miner. No one could explain how the mule carrying the large crucifix was able to fit through the door to get into the house because a group of men could not get the object back out through the door. So, the Señor de los Plateros had to remain in the tiny town of San Demetrio in that miner’s house. People came to visit the Christ and eventually the small house was converted into a chapel, then torn down, with a larger church built on the same spot sometime later.

In another version of the story involves the miraculous appearance of the large cross in the deserts outside the town of San Demetrio right after the town was built in the mid-1500s. News of the beautiful crucifix drew people out to the desert to see it and had many people in the town debating about how it got there and what to do with it. Some people reasoned that it had probably belonged to a frontier mission or church that had been raided and looted by marauding Huicholes or Chichimecas. The Indians had no use for the crucifix, so they just dumped it in the desert. Should they bring it into town? Some people cautioned against it for fear that the object was a sort of evilly charged Trojan Horse. Those who believe this thought the object was carrying a Native curse on it and it was left in the desert as a sort of bait. The intention of those who left it there was for it to be brought into town so it would infect the Spanish settlement with all the bad mojo the Indian shamans instilled in it. The ones who thought the Christ could have possibly been cursed lost out to the others who wanted to bring the beautiful crucifix into town. As the Señor de los Plateros has been credited with many miracles and healings over the centuries, to the faithful, the native curse camp was proved wrong.

After a few centuries of silver mining the region became very prosperous, and as previously mentioned, the town of Plateros started constructing a new, much larger church in the 1780s. A wealthy silver miner in the region wanted to contribute to the construction of the new church, so he donated a large statue of Nuestra Señora de Atocha, or in English, Our Lady of Atocha. This statue, or rather an element of it, would later surpass the Señor de los Plateros crucifix in its importance at this pilgrimage site. The Virgin of Atocha had been venerated in Spain since the 13th Century when a great deal of territory of that country was under Muslim rule. In the town of Atocha near Madrid, a chapel housed a beautiful carving of the Virgin Mary with a small Christ Child which drew pilgrims from the immediate area. When Atocha fell to the Muslims, many Christians were taken prisoner. The prisoners were not fed by jailers and were only given food by their families when they were allowed to visit. The visitation laws became stricter with time and only children were allowed to see prisoners and bring food. Those imprisoned men who had no small children could therefore not get any food. According to the story, the women of Atocha prayed to the statue of the Virgin Mary and asked her for her help. It was said that in the middle of the night the Christ Child, or Santo Niño, attached to the statue, would walk around, and give food to the prisoners who needed it. The stories were verified when people started noticing that the shoes on the Santo Niño were scuffed, as if from excessive walking. The image of the Santo Niño de Atocha is easily recognizable as he is currently popular in many countries throughout Latin America. He is dressed as a pilgrim wearing a blue robe and brownish-red cloak. He has a feathered hat and he carries two things: a basket of food and a staff with a water gourd attached. In artistic renditions he is usually pictured comfortably seated and wearing sandals. On his cape there is a scallop shell, symbolizing a pilgrimage to the shrine of Saint James. Smiling cherubs are suspended above the Santo Niño and fancy flower vases are at his feet. His hair tends to be curly and at shoulder length and his facial features are always soft and delicate, almost feminine.

After a few centuries of silver mining the region became very prosperous, and as previously mentioned, the town of Plateros started constructing a new, much larger church in the 1780s. A wealthy silver miner in the region wanted to contribute to the construction of the new church, so he donated a large statue of Nuestra Señora de Atocha, or in English, Our Lady of Atocha. This statue, or rather an element of it, would later surpass the Señor de los Plateros crucifix in its importance at this pilgrimage site. The Virgin of Atocha had been venerated in Spain since the 13th Century when a great deal of territory of that country was under Muslim rule. In the town of Atocha near Madrid, a chapel housed a beautiful carving of the Virgin Mary with a small Christ Child which drew pilgrims from the immediate area. When Atocha fell to the Muslims, many Christians were taken prisoner. The prisoners were not fed by jailers and were only given food by their families when they were allowed to visit. The visitation laws became stricter with time and only children were allowed to see prisoners and bring food. Those imprisoned men who had no small children could therefore not get any food. According to the story, the women of Atocha prayed to the statue of the Virgin Mary and asked her for her help. It was said that in the middle of the night the Christ Child, or Santo Niño, attached to the statue, would walk around, and give food to the prisoners who needed it. The stories were verified when people started noticing that the shoes on the Santo Niño were scuffed, as if from excessive walking. The image of the Santo Niño de Atocha is easily recognizable as he is currently popular in many countries throughout Latin America. He is dressed as a pilgrim wearing a blue robe and brownish-red cloak. He has a feathered hat and he carries two things: a basket of food and a staff with a water gourd attached. In artistic renditions he is usually pictured comfortably seated and wearing sandals. On his cape there is a scallop shell, symbolizing a pilgrimage to the shrine of Saint James. Smiling cherubs are suspended above the Santo Niño and fancy flower vases are at his feet. His hair tends to be curly and at shoulder length and his facial features are always soft and delicate, almost feminine.

In the Mexican church at Plateros the imported replica of Our Lady of Atocha donated by the wealthy miner had a detachable Baby Jesus. Caretakers and priests at the new church would remove the Santo Niño and honor it with festivities and special masses on December 24th and 25th. By the beginning of the 1800s devotion to the Santo Niño started to become the main draw to the church. The Santo Niño de Atocha was permanently detached from the Virgin Mary statue and moved from the side of the church to a glass box placed right under the main crucifix, the much older Lord of Plateros. The elevation of his status occurred when something happened similar to the feeding of the prisoners in Muslim-occupied Spain centuries before. In the first decade of the 1800s there was an explosion in one of the mines outside the town of Plateros. There were many miners who were trapped, and it was well over a week before they were rescued. During the time the miners were in peril, visitors to the church noticed that the Santo Niño statue was missing. Believers attested that it was the Baby Jesus himself who was tending to the trapped miners and was seeing them through the crisis. When the Santo Niño statue appeared again in the church it was dusty and dirty, as if it had been down in the mines assisting with the rescue efforts. While this seemed to be a fantastic story, throughout north-central Mexico, the healing powers of the Santo Niño became legendary. He became the unofficial patron saint of miners, the sick, prisoners, and those facing immediate danger.

In the Mexican church at Plateros the imported replica of Our Lady of Atocha donated by the wealthy miner had a detachable Baby Jesus. Caretakers and priests at the new church would remove the Santo Niño and honor it with festivities and special masses on December 24th and 25th. By the beginning of the 1800s devotion to the Santo Niño started to become the main draw to the church. The Santo Niño de Atocha was permanently detached from the Virgin Mary statue and moved from the side of the church to a glass box placed right under the main crucifix, the much older Lord of Plateros. The elevation of his status occurred when something happened similar to the feeding of the prisoners in Muslim-occupied Spain centuries before. In the first decade of the 1800s there was an explosion in one of the mines outside the town of Plateros. There were many miners who were trapped, and it was well over a week before they were rescued. During the time the miners were in peril, visitors to the church noticed that the Santo Niño statue was missing. Believers attested that it was the Baby Jesus himself who was tending to the trapped miners and was seeing them through the crisis. When the Santo Niño statue appeared again in the church it was dusty and dirty, as if it had been down in the mines assisting with the rescue efforts. While this seemed to be a fantastic story, throughout north-central Mexico, the healing powers of the Santo Niño became legendary. He became the unofficial patron saint of miners, the sick, prisoners, and those facing immediate danger.

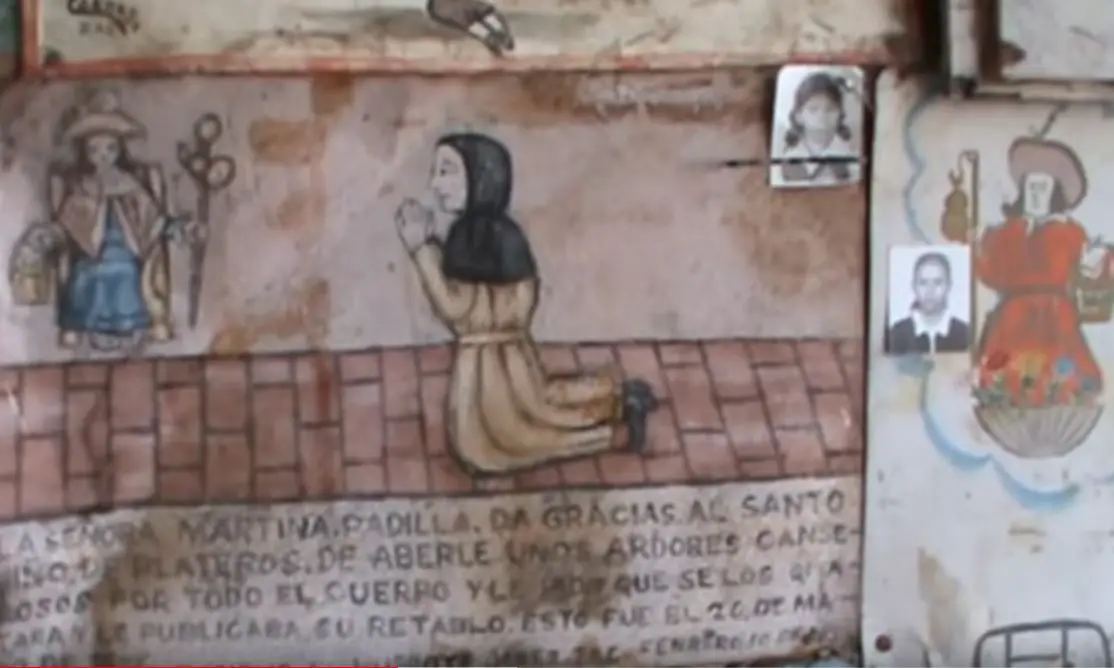

Some researchers believe that the story of the disappearing statue helping the miners may have been made up decades later to serve specific political purposes. After Mexican independence in the 1820s, the Catholic Church in Mexico found itself with an uncertain future. Often associated with Spanish imperialism, the Church in a newly independent Mexico had to find its way and was often met with contempt from ambitious politicians who saw the Church as either a threat to their power or just a relic from the old power structure that needed to be done away with. While anticlerical politicians turned up the heat on the Church, many within the Church saw the need to consolidate or enhance their own power. In 1820s and 1830s Mexico, this promotion of power often took the form of elevating certain saints and virgins to local protector status. Encouraging important shrines and sanctuaries was part of the Mexican church’s plan to have power over the people in a more divine way. It was hard for the government to compete against an institution that derived its authority from the Almighty and the Church localized its power through the shrines. People could connect directly with a manifestation of heavenly power that was more personal because it was intimately tied to their immediate geographical area. As the promotion of the Santo Niño grew, so  did the pilgrimages. Pilgrims were encouraged to bring offerings in the form of personal objects or ex votos, painted stories depicting a miracle or other event for which the devotee is thankful. A big development in the expansion of the devotion of the Santo Niño at Plateros came in the promulgation of a novena, or formal nine days of prayer, in which 9 miracles taken directly from ex votos left by pilgrims were incorporated into the prayers. The novena to the Santo Niño was published by a local press in a Mexican version of Spanish that was less formal than the European Spanish the churchgoers were used to. The Santo Niño had thus become the patron and helper of the common person. The Church had won their battle with the government for the hearts and minds of the people, at least in this region of the Republic. Over the years the Santo Niño would be credited with many miracles from healing the sick to helping with finances to interceding in situations involving incarcerated persons.

did the pilgrimages. Pilgrims were encouraged to bring offerings in the form of personal objects or ex votos, painted stories depicting a miracle or other event for which the devotee is thankful. A big development in the expansion of the devotion of the Santo Niño at Plateros came in the promulgation of a novena, or formal nine days of prayer, in which 9 miracles taken directly from ex votos left by pilgrims were incorporated into the prayers. The novena to the Santo Niño was published by a local press in a Mexican version of Spanish that was less formal than the European Spanish the churchgoers were used to. The Santo Niño had thus become the patron and helper of the common person. The Church had won their battle with the government for the hearts and minds of the people, at least in this region of the Republic. Over the years the Santo Niño would be credited with many miracles from healing the sick to helping with finances to interceding in situations involving incarcerated persons.

Today, the Plateros church is one of the most-visited religious shrines in all Mexico. The delicate Santo Niño still has his place in a glass box directly beneath the crucifix depicting the Lord of Plateros which is now almost 500 years old. Over the years the Baby Jesus statue has gotten many make-overs and wardrobe changes and he is still celebrated every Christmas. The devotional painting, the ex votos, encouraged to be brought to the sanctuary as testimonies of the faithful have now overwhelmed the church complex. Thousands of these artistic representations of thanks are on display for the public in the colonnades and hallways flanking the main church. Millions of people attest to the many miracles of Plateros. The devotion continues.

REFERENCES

Plateros Official Web site

Comack, Marilyn, ed. Saints and Their Cults in the Atlantic World. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 2007. We are Amazon affiliates. Buy the book on Amazon here: https://amzn.to/2ADxoZv