Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

In the year 2003 the Mexican Congress passed legislation called “The Law of Linguistic Rights.” The law recognized the legal coexistence of Spanish with 63 other Native American languages for all official purposes in the country. Article 7 in The Law of Linguistic Rights states: “The Mexican indigenous languages would be valid, at the same degree as Spanish, for any issue or public procedure, and also in order to access to the public procedures, services and information.” Thus, the law required the government to offer all services in an indigenous citizen’s native tongue provided the language made the official government list of 63. Since a formal governmental infrastructure did not exist to facilitate the requirements of the new law, in the same year Mexico established The National Institute of Indigenous Languages to protect, formalize and promote the use of indigenous languages in the country. The institute – known by its Spanish acronym of INALI – has been working closely with the native Mexican cultures in order to formalize and give more structure to their languages. After the creation of the INALI most of the native languages have seen a slight increase in their number of speakers. While upwards of 97% of the Mexican population speaks Spanish, some 6% of the country speaks an indigenous language. That means a little over 6 million people in Mexico speak a Native American language. The top ten indigenous languages in Mexico all have speakers that number into the hundreds of thousands and even over a million in the case of Nahuatl, or the language of the Aztecs. Nahuatl currently has about 1.7 million fluent speakers in all parts of Mexico and in some areas of the United States settled by Mexican migrants. One in four of all speakers of native languages in Mexico speaks the old Aztec language. Nahuatl was the official language of the Aztec Empire before it was conquered by the Spanish and served as the lingua franca of central Mexico before the Europeans arrived. According to Wikipedia, “lingua franca” refers to any language used for communication between people who do not share a native language. Nahuatl was used among the subjugated people throughout the Aztec Empire and beyond for communications having to do with trade, religion and diplomacy. The language was so widely used among so many peoples in so many regions of what is now Mexico that in 1670, some 50 years after the Conquest, the Spanish king Phillip the Second declared Nahuatl to be the official language of the colonies of New Spain. As more and more natives and their descendants of various groups learned Spanish, the use of Nahuatl became less important. Some 26 years after King Phillip the Second’s decree, a new king, Charles the Second, reversed the law and effectively outlawed the public use of all indigenous languages throughout New Spain. It was only during what is termed Mexico’s Second Empire in the middle of the 1800s under the Austrian-born Hapsburg Emperor Maximilian did indigenous languages get the attention of the Mexican government. During the emperor’s short reign he sought to encourage Nahuatl and other indigenous languages alongside Spanish. At the time of Emperor Maximilian it is estimated that a little over 40% of Mexicans knew an indigenous language compared to the 6% of the country today. It is important to note that even though there are 63 languages on the government’s official list of indigenous languages that are co-equal with Spanish, there really exist some 280 distinct Native American languages in Mexico, if we are to include that which have been historically referred to as “dialects” within a language that are mutually unintelligible. Lesser-used indigenous languages began attracting attention from foreign academics in the first half of the 20th Century in a race to catalog vocabularies and oral histories of vanishing cultures. The Mexican federal and state governments have paid little attention to native languages until recently with special emphasis given to those with fewer speakers.

In the year 2003 the Mexican Congress passed legislation called “The Law of Linguistic Rights.” The law recognized the legal coexistence of Spanish with 63 other Native American languages for all official purposes in the country. Article 7 in The Law of Linguistic Rights states: “The Mexican indigenous languages would be valid, at the same degree as Spanish, for any issue or public procedure, and also in order to access to the public procedures, services and information.” Thus, the law required the government to offer all services in an indigenous citizen’s native tongue provided the language made the official government list of 63. Since a formal governmental infrastructure did not exist to facilitate the requirements of the new law, in the same year Mexico established The National Institute of Indigenous Languages to protect, formalize and promote the use of indigenous languages in the country. The institute – known by its Spanish acronym of INALI – has been working closely with the native Mexican cultures in order to formalize and give more structure to their languages. After the creation of the INALI most of the native languages have seen a slight increase in their number of speakers. While upwards of 97% of the Mexican population speaks Spanish, some 6% of the country speaks an indigenous language. That means a little over 6 million people in Mexico speak a Native American language. The top ten indigenous languages in Mexico all have speakers that number into the hundreds of thousands and even over a million in the case of Nahuatl, or the language of the Aztecs. Nahuatl currently has about 1.7 million fluent speakers in all parts of Mexico and in some areas of the United States settled by Mexican migrants. One in four of all speakers of native languages in Mexico speaks the old Aztec language. Nahuatl was the official language of the Aztec Empire before it was conquered by the Spanish and served as the lingua franca of central Mexico before the Europeans arrived. According to Wikipedia, “lingua franca” refers to any language used for communication between people who do not share a native language. Nahuatl was used among the subjugated people throughout the Aztec Empire and beyond for communications having to do with trade, religion and diplomacy. The language was so widely used among so many peoples in so many regions of what is now Mexico that in 1670, some 50 years after the Conquest, the Spanish king Phillip the Second declared Nahuatl to be the official language of the colonies of New Spain. As more and more natives and their descendants of various groups learned Spanish, the use of Nahuatl became less important. Some 26 years after King Phillip the Second’s decree, a new king, Charles the Second, reversed the law and effectively outlawed the public use of all indigenous languages throughout New Spain. It was only during what is termed Mexico’s Second Empire in the middle of the 1800s under the Austrian-born Hapsburg Emperor Maximilian did indigenous languages get the attention of the Mexican government. During the emperor’s short reign he sought to encourage Nahuatl and other indigenous languages alongside Spanish. At the time of Emperor Maximilian it is estimated that a little over 40% of Mexicans knew an indigenous language compared to the 6% of the country today. It is important to note that even though there are 63 languages on the government’s official list of indigenous languages that are co-equal with Spanish, there really exist some 280 distinct Native American languages in Mexico, if we are to include that which have been historically referred to as “dialects” within a language that are mutually unintelligible. Lesser-used indigenous languages began attracting attention from foreign academics in the first half of the 20th Century in a race to catalog vocabularies and oral histories of vanishing cultures. The Mexican federal and state governments have paid little attention to native languages until recently with special emphasis given to those with fewer speakers.

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, or UNESCO, describes four levels of language endangerment between “safe” (not endangered) and “extinct” (no living speakers), based on intergenerational transfer of language. The fist level is “vulnerable,” meaning the language is not spoken by children outside the home. The second level is “definitely endangered” in which children are not speaking the language. The third level is termed “severely endangered,” and this means the language is only spoken by the oldest generations. The last level before language extinction is called “critically endangered.” In this level the language is spoken by few members of the oldest generation and those speakers are not often fluent. There are a dozen or so indigenous languages in Mexico that are at the critically endangered stage and set to go extinct within the next 10 years. Perhaps the rarest language is Kiliwa once spoken by many people in the far northwestern corner of the Mexican state of Baja California near modern-day Tijuana. The Mexican census taken in the year 2000 reported 52 speakers of Kiliwa. 18 years later that number had dropped from 52 to just 4 people. There are no efforts to revive this language.

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, or UNESCO, describes four levels of language endangerment between “safe” (not endangered) and “extinct” (no living speakers), based on intergenerational transfer of language. The fist level is “vulnerable,” meaning the language is not spoken by children outside the home. The second level is “definitely endangered” in which children are not speaking the language. The third level is termed “severely endangered,” and this means the language is only spoken by the oldest generations. The last level before language extinction is called “critically endangered.” In this level the language is spoken by few members of the oldest generation and those speakers are not often fluent. There are a dozen or so indigenous languages in Mexico that are at the critically endangered stage and set to go extinct within the next 10 years. Perhaps the rarest language is Kiliwa once spoken by many people in the far northwestern corner of the Mexican state of Baja California near modern-day Tijuana. The Mexican census taken in the year 2000 reported 52 speakers of Kiliwa. 18 years later that number had dropped from 52 to just 4 people. There are no efforts to revive this language.

The Ayapaneco language, spoken in a remote valley in the Mexican state of Tabasco provides an interesting case study of a language revival based on a hoax. In 2014 British telecom giant Vodafone put forth a marketing campaign to save the Ayapaneco language. According to their story, there were only 2 speakers of the language left, two old men, Manuel Segovia and Isidro Velazquez, and they refused to speak to one another because of a feud dating back decades. The British company went to their town, paid for a school to be built, helped the two elderly speakers reconcile and the language is now being taught to children. According to an article titled, “The Marketing Campaign that Endangered a Language” on the Ripley’s Believe it or Not! website, in the year 2008 the Mexican government had already been paying Isidro Velazquez, his son and 4 other fluent speakers, to teach Ayapenaco to children, as an Ayapenaco vocabulary and teaching materials had recently been developed by a linguist studying the language. This was 6 years before Vodafone came to town. The British company did not build a new school, but just painted an old one and paid the two elderly men to appear in the ads and go along with the story, while excluding other Ayapenaco speakers. This hoax created conflict in the village with new feuds popping up and resulted in diminished interest in attending Ayapenaco language classes.

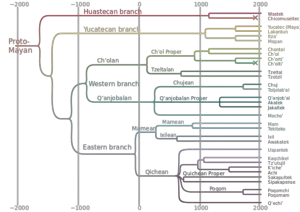

The indigenous languages of Mexico are grouped into larger families of languages with many languages within those families only slightly related. The largest families are the Uto-Aztecan family and the Mayan family of languages. To give an idea of the breakdown, the Uto-Aztecan family has 4 branches that consist of 12 distinct languages. The Mayan family has 5 branches and 19 different languages. Besides Uto-Aztecan and Mayan, there are 4 other language families that have dozens of unique languages among them. In addition to these large language families there also exist 4 language isolates among the indigenous languages of Mexico. Wikipedia defines a “language isolate” as “a natural language with no demonstrable genealogical (or “genetic”) relationship with other languages, one that has not been demonstrated to descend from an ancestor common with any other language. Language isolates are in effect language families consisting of a single language.” The isolates add a bit of mystery to Mexico’s language table. No one knows where the languages come from and by extension the people who speak these unique languages are a bit of a mystery themselves. The largest language isolate in Mexico is Purépucha, spoken by a quarter of a million people in the state of Michoacán. This language is also known as Tarascan. The second-largest Mexican indigenous language isolate is Huave, spoken in four villages on the Paific coast of Oaxaca and has around 18,000 speakers. The next is the Chontal dialects spoken by 4,400 people in southern Oaxaca. The Chontal dialects are often grouped together and called the Tequistlatecan language. The most endangered of the Mexican language isolates is Seri, spoken by only 700 or so people in two fishing villages on the northern coast of the Sea of Cortez in the state of Sonora. UNESCO classifies Seri as “vulnerable” because it is not spoken by children outside the home. Without significant revival efforts Seri may disappear in two generations. Curiously, even after Seri is gone at least one word will live on in the scientific annals. Mexican biologist Juan Carlos Pérez Jiménez decided to incorporate the Seri word for shark – hacat – into the name of a newly identified species of smooth-hound shark which only lives in the Sea of Cortez. The new shark’s scientific name is Mustulus hacat.

The indigenous languages of Mexico are grouped into larger families of languages with many languages within those families only slightly related. The largest families are the Uto-Aztecan family and the Mayan family of languages. To give an idea of the breakdown, the Uto-Aztecan family has 4 branches that consist of 12 distinct languages. The Mayan family has 5 branches and 19 different languages. Besides Uto-Aztecan and Mayan, there are 4 other language families that have dozens of unique languages among them. In addition to these large language families there also exist 4 language isolates among the indigenous languages of Mexico. Wikipedia defines a “language isolate” as “a natural language with no demonstrable genealogical (or “genetic”) relationship with other languages, one that has not been demonstrated to descend from an ancestor common with any other language. Language isolates are in effect language families consisting of a single language.” The isolates add a bit of mystery to Mexico’s language table. No one knows where the languages come from and by extension the people who speak these unique languages are a bit of a mystery themselves. The largest language isolate in Mexico is Purépucha, spoken by a quarter of a million people in the state of Michoacán. This language is also known as Tarascan. The second-largest Mexican indigenous language isolate is Huave, spoken in four villages on the Paific coast of Oaxaca and has around 18,000 speakers. The next is the Chontal dialects spoken by 4,400 people in southern Oaxaca. The Chontal dialects are often grouped together and called the Tequistlatecan language. The most endangered of the Mexican language isolates is Seri, spoken by only 700 or so people in two fishing villages on the northern coast of the Sea of Cortez in the state of Sonora. UNESCO classifies Seri as “vulnerable” because it is not spoken by children outside the home. Without significant revival efforts Seri may disappear in two generations. Curiously, even after Seri is gone at least one word will live on in the scientific annals. Mexican biologist Juan Carlos Pérez Jiménez decided to incorporate the Seri word for shark – hacat – into the name of a newly identified species of smooth-hound shark which only lives in the Sea of Cortez. The new shark’s scientific name is Mustulus hacat.

Not all minority languages in Mexico are indigenous. In fact, the largest minority language spoken in Mexico with almost 16 million speakers, or 13% of the entire country’s population, is English! There are small pockets of historical English speakers in Mexico, most notably the Mormon colonies of Chihuahua and Sonora established in the mid-1800s, and the large expatriate community around Lake Chapala in the state of Jalisco which dates to the early 1920s. As English is the second language of the world, it is not surprising that so many English speakers exist in Mexico, but the country’s proximity to the United States and the fluid nature of immigration between the countries only makes the number of English speakers greater in Mexico than in most other countries where English is not the native language. In addition, many guest workers in Mexico come from the English-speaking world, and English is a lingua franca of sorts used by many foreigners in Mexican resorts. Besides English, perhaps the next largest non-indigenous minority language in Mexico is a Low Prussian dialect of East Low German spoken by members of Mexico’s Mennonite communities in the states of Chihuahua, Durango and Campeche. Although no formal count has been taken, linguists estimate that 40,000 people in Mexico speak this old dialect of German that had its origins in the Russian Empire. The most curious example of a European minority language in Mexico exists in the town of Chipilo in the Mexican state of Puebla. The town was settled by some 500 Venetian immigrants from Italy in the 1800s and some 2,500 people in Chipilo today speak a northern dialect of the Venetian language. Many erroneously assume that the language of Venice and its surrounding areas – called Veneto in Venetian – is a dialect of Italian, but it is not. It is a distinct member of the Romance language family spoken by almost 4 million people in northeastern Italy and a small part of Slovenia. The Venetian language enjoyed great prestige during the height of the Venetian Republic which lasted from the 8th Century to the 18th Century and was the language of trade throughout the Mediterranean world for hundreds of years. The Venetian spoken in the Mexican town of Chipilo has been frozen in time and its population, for the most part, has remained separate from Mexican society until about 40

Not all minority languages in Mexico are indigenous. In fact, the largest minority language spoken in Mexico with almost 16 million speakers, or 13% of the entire country’s population, is English! There are small pockets of historical English speakers in Mexico, most notably the Mormon colonies of Chihuahua and Sonora established in the mid-1800s, and the large expatriate community around Lake Chapala in the state of Jalisco which dates to the early 1920s. As English is the second language of the world, it is not surprising that so many English speakers exist in Mexico, but the country’s proximity to the United States and the fluid nature of immigration between the countries only makes the number of English speakers greater in Mexico than in most other countries where English is not the native language. In addition, many guest workers in Mexico come from the English-speaking world, and English is a lingua franca of sorts used by many foreigners in Mexican resorts. Besides English, perhaps the next largest non-indigenous minority language in Mexico is a Low Prussian dialect of East Low German spoken by members of Mexico’s Mennonite communities in the states of Chihuahua, Durango and Campeche. Although no formal count has been taken, linguists estimate that 40,000 people in Mexico speak this old dialect of German that had its origins in the Russian Empire. The most curious example of a European minority language in Mexico exists in the town of Chipilo in the Mexican state of Puebla. The town was settled by some 500 Venetian immigrants from Italy in the 1800s and some 2,500 people in Chipilo today speak a northern dialect of the Venetian language. Many erroneously assume that the language of Venice and its surrounding areas – called Veneto in Venetian – is a dialect of Italian, but it is not. It is a distinct member of the Romance language family spoken by almost 4 million people in northeastern Italy and a small part of Slovenia. The Venetian language enjoyed great prestige during the height of the Venetian Republic which lasted from the 8th Century to the 18th Century and was the language of trade throughout the Mediterranean world for hundreds of years. The Venetian spoken in the Mexican town of Chipilo has been frozen in time and its population, for the most part, has remained separate from Mexican society until about 40  years ago. Because the Venetian of Chipilo has not been influenced by Mexican Spanish or Italian as the language has in Italy, linguists point out that the Venetian spoken in Mexico is a purer form of the language than that found in modern-day Venice. Children in Chipilo grow up speaking Venetian inside and outside the home, so there is no concern that this language will die out in Mexico anytime soon, although the town is changing and many Mexican Spanish-speakers with no interest in learning Venetian have settled in the town.

years ago. Because the Venetian of Chipilo has not been influenced by Mexican Spanish or Italian as the language has in Italy, linguists point out that the Venetian spoken in Mexico is a purer form of the language than that found in modern-day Venice. Children in Chipilo grow up speaking Venetian inside and outside the home, so there is no concern that this language will die out in Mexico anytime soon, although the town is changing and many Mexican Spanish-speakers with no interest in learning Venetian have settled in the town.

Often thought as monolingual, Mexico is a land of hundreds of languages and much linguistic variety. With the dominance of Spanish and the ever-growing importance of English as a world language, many of the minority languages of Mexico may disappear in our lifetimes in spite of government efforts to preserve and to revive them. Who knows what unique knowledge and forms of expression will die out along with them?

REFERENCES

Wikipedia

The “Ripley’s Believe it or Not!” website