Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

Buy the show’s official t-shirt here: https://teespring.com/chichimeca?tsmac=store&tsmic=mexico-unexplained&pid=2&cid=573

Buy the show’s official t-shirt here: https://teespring.com/chichimeca?tsmac=store&tsmic=mexico-unexplained&pid=2&cid=573

On many old maps of Mexico there are large areas of land to the north of the Spanish colonies in the former Aztec lands of central Mexico with a sweeping label: La Gran Chichimeca. In the language of the Aztecs, Nahuatl, the words chichimeca or chichimécatl mean, “the inhabitants of the land of Chichiman.” The word “Chichiman” translates to “The Land of Milk,” in English. The Aztecs used this term to describe the modern-day Mexican bajio region located on the northern fringes of their empire and beyond. This area had very few permanent settlements and consisted of rugged mountains and stark deserts. The inhabitants of this largely unexplored and unknown territory were called collectively “Chichimeca” by the Aztecs. The word Chichimeca would soon be associated with the terms, “barbarian” or “uncivilized,” in the Aztec language and later the same with the Spanish. Although claiming a mythical connection to the older civilization of the Toltecs, which had been long gone when the Aztecs arrived in central Mexico, the more “civilized” and sedentary Aztecs admitted reluctantly to their new Spanish overlords that they too were once Chichimeca, as they had lived a mostly nomadic existence in the north just a few centuries earlier. Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortéz was the first European to describe the Chichimecs by name in a letter he sent back to Spain. He wrote that these Indians who were not as civilized to him as the Aztecs and would make good slaves to be used to work the mines of New Spain. In modern-day Mexico, the word “Chichimeca” has survived and is casually thrown around and applied to anyone exhibiting bad behavior. Who were the real Chichimeca of history and do they still exist in present-day Mexico?

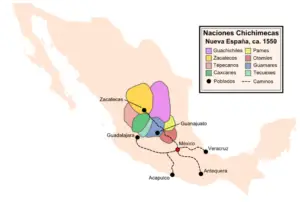

Historians and other researchers identify about a half dozen distinct indigenous groups as being historically Chichimeca. Since Aztec times the people of the north had been painted with a broad brush and even though these distinct groups had separate languages they were united by certain cultural practices and lived in the same environment. Scholars disagree on which pre-Hispanic peoples can be lumped together to be called “Chichimeca” and the names on the list change. Early Spanish accounts name the Guachichil, the Caxcan, the Zacateco, the Tecuexe and the Guamare while scholars also place the Opata and the Eudeve peoples on the list. The Chichimeca lived a hunter-gatherer, nomadic existence. Those groups in the southern part of their homeland, the ones closest to the territories of the Aztec Empire, engaged in basic farming, mostly squash and maize. Overall, though, the Chichimec diet consisted primarily of small game and edible parts of desert plants such as mesquite beans, the pads and fruit of cactus, roots, and the heart of the agave. Because most of the Chichimeca lived a nomadic existence, they constructed temporary shelters of sticks and desert plants. Some lived in caves. The ones who were more agricultural had more permanent dwellings, but these were fashioned in the same style as the nomadic structures. Early Spanish chroniclers noted that the Chichimeca did not have a formalized religious belief system and were more animistic, in that they believed in spirits connected with nature and attached to specific locations. Some of the tribes closest to Aztec lands, such as the Pames, had lukewarm adherence to the religions of the larger Mesoamerican civilizations and occasionally worshipped the Aztec gods. When the Spanish first encountered the Chichimeca, they described them as “Hijos del Viento,” or “Children of the Wind” the name that some Chichimeca called themselves in their respective languages. It was an apt descriptor to use to contrast with the more sedentary Aztecs. The Chichimeca had long been at odds with the indigenous super-civilization to their south. They fought off every single Aztec intrusion into their territories and the greatest empire ancient Mexico had ever seen had a hard time expanding into the north. The Chichimecs’ fierce distrust of foreigners would cause them to go toe to toe with one of the greatest empires in the world at the time, Spain, and they would fight a protracted guerilla war with the Spanish that lasted some 40 years and ended with the mighty Spanish paying for peace.

Historians and other researchers identify about a half dozen distinct indigenous groups as being historically Chichimeca. Since Aztec times the people of the north had been painted with a broad brush and even though these distinct groups had separate languages they were united by certain cultural practices and lived in the same environment. Scholars disagree on which pre-Hispanic peoples can be lumped together to be called “Chichimeca” and the names on the list change. Early Spanish accounts name the Guachichil, the Caxcan, the Zacateco, the Tecuexe and the Guamare while scholars also place the Opata and the Eudeve peoples on the list. The Chichimeca lived a hunter-gatherer, nomadic existence. Those groups in the southern part of their homeland, the ones closest to the territories of the Aztec Empire, engaged in basic farming, mostly squash and maize. Overall, though, the Chichimec diet consisted primarily of small game and edible parts of desert plants such as mesquite beans, the pads and fruit of cactus, roots, and the heart of the agave. Because most of the Chichimeca lived a nomadic existence, they constructed temporary shelters of sticks and desert plants. Some lived in caves. The ones who were more agricultural had more permanent dwellings, but these were fashioned in the same style as the nomadic structures. Early Spanish chroniclers noted that the Chichimeca did not have a formalized religious belief system and were more animistic, in that they believed in spirits connected with nature and attached to specific locations. Some of the tribes closest to Aztec lands, such as the Pames, had lukewarm adherence to the religions of the larger Mesoamerican civilizations and occasionally worshipped the Aztec gods. When the Spanish first encountered the Chichimeca, they described them as “Hijos del Viento,” or “Children of the Wind” the name that some Chichimeca called themselves in their respective languages. It was an apt descriptor to use to contrast with the more sedentary Aztecs. The Chichimeca had long been at odds with the indigenous super-civilization to their south. They fought off every single Aztec intrusion into their territories and the greatest empire ancient Mexico had ever seen had a hard time expanding into the north. The Chichimecs’ fierce distrust of foreigners would cause them to go toe to toe with one of the greatest empires in the world at the time, Spain, and they would fight a protracted guerilla war with the Spanish that lasted some 40 years and ended with the mighty Spanish paying for peace.

The Chichimeca War began eight years after the end of the Mixtón War, which was the first major indigenous uprising in New Spain after the fall of the Aztecs. For more about the Mixtón War, please see Mexico Unexplained Episode Number 88. Some scholars argue that the Spanish war with the Chichimecs was only a continuation of the Mixtón War, as sporadic fighting broke out between the natives and the Spanish in the form of skirmishes in the intervening years. The Spanish had little interest in the arid northern regions beyond the original Aztec heartland until a man named Juan de Tolosa arrived in the region of the modern-day city of Zacatecas. In September of 1546, near the Cerro de la Bufa, the natives showed Tolosa pieces of silver-rich ore. When news of this discovery spread throughout New Spain, large numbers of Spaniards began migrating into Chichimeca territory looking for silver. In the beginning, the Chichimec people resented Spanish intrusion into their ancestral lands and responded with mild hostility. Spanish roads acting as supply lines for the mines cut across sacred lands with little concern for the natives. It was not until the Spanish started raiding the indigenous camps to round up slaves for the silver mines that the Chichimeca began to organize and a formal resistance against Spanish authority began to coalesce. This new Chichimec Confederation consisted chiefly of the Zacatecos, Guachichiles, Pumes and Guamares, but people as far away as the southern part of the modern-day US state of Arizona participated in the resistance. In addition to having a home-court advantage over the Spanish, the Chichimecs possessed a secret weapon of sorts that helped them resist the invaders for 4 decades. Described by an early Spanish writer as being “the best archers in the world,” the Chichimeca had a unique bow and arrow combination that helped them win battles against a supposedly more technologically advanced European war machine. The Chichimec bows were about 4 feet long, which were much shorter than bows used by the Spaniards. Their arrows were made of thin reeds and tipped with Mexican obsidian, a hard, volcanic glass that was knapped into sharp points. The obsidian-tipped arrows could pierce the Spanish chain mail armor with ease. In fact, they seemed to slice through anything. In one account of the war, a soldier riding with a commander named Alonso de Castilla died when a Chichimec arrow passed through the head of a horse, including a crownpiece made of double buckskin and metal, and into his chest. One arrow killed both horse and rider. The Chichimecs were experts in navigating the rough terrain of

The Chichimeca War began eight years after the end of the Mixtón War, which was the first major indigenous uprising in New Spain after the fall of the Aztecs. For more about the Mixtón War, please see Mexico Unexplained Episode Number 88. Some scholars argue that the Spanish war with the Chichimecs was only a continuation of the Mixtón War, as sporadic fighting broke out between the natives and the Spanish in the form of skirmishes in the intervening years. The Spanish had little interest in the arid northern regions beyond the original Aztec heartland until a man named Juan de Tolosa arrived in the region of the modern-day city of Zacatecas. In September of 1546, near the Cerro de la Bufa, the natives showed Tolosa pieces of silver-rich ore. When news of this discovery spread throughout New Spain, large numbers of Spaniards began migrating into Chichimeca territory looking for silver. In the beginning, the Chichimec people resented Spanish intrusion into their ancestral lands and responded with mild hostility. Spanish roads acting as supply lines for the mines cut across sacred lands with little concern for the natives. It was not until the Spanish started raiding the indigenous camps to round up slaves for the silver mines that the Chichimeca began to organize and a formal resistance against Spanish authority began to coalesce. This new Chichimec Confederation consisted chiefly of the Zacatecos, Guachichiles, Pumes and Guamares, but people as far away as the southern part of the modern-day US state of Arizona participated in the resistance. In addition to having a home-court advantage over the Spanish, the Chichimecs possessed a secret weapon of sorts that helped them resist the invaders for 4 decades. Described by an early Spanish writer as being “the best archers in the world,” the Chichimeca had a unique bow and arrow combination that helped them win battles against a supposedly more technologically advanced European war machine. The Chichimec bows were about 4 feet long, which were much shorter than bows used by the Spaniards. Their arrows were made of thin reeds and tipped with Mexican obsidian, a hard, volcanic glass that was knapped into sharp points. The obsidian-tipped arrows could pierce the Spanish chain mail armor with ease. In fact, they seemed to slice through anything. In one account of the war, a soldier riding with a commander named Alonso de Castilla died when a Chichimec arrow passed through the head of a horse, including a crownpiece made of double buckskin and metal, and into his chest. One arrow killed both horse and rider. The Chichimecs were experts in navigating the rough terrain of  the theater of war. Their nomadic culture made them experts at living off the land. The Spanish, already at a distinct disadvantage being strangers in unfamiliar territory, relied on supply lines and livestock to feed their war machine. The Chichimecs organized in raiding parties of 5 to 200 people, and ambushed the supply lines and killed off the livestock, thus effectively slowing down the Spanish, almost to a standstill in some instances. The promise of loot from raids attracted many warriors from faraway tribes, thus ensuring a never-ending and fresh supply of enthusiastic, able-bodied men to fight the Spanish. Chichimec guerilla tactics often turned numerical disadvantages into victories. In one account, outnumbered four to one, some fifty Zacateco fighters attached a contingent of 200 Spanish troops and defeated them. In the early part of the war, the Chichimecs captured Spanish horses and learned to ride them. Because of this, the Chichimec War was the first time the Spanish ever faced mounted indigenous warriors in the New World.

the theater of war. Their nomadic culture made them experts at living off the land. The Spanish, already at a distinct disadvantage being strangers in unfamiliar territory, relied on supply lines and livestock to feed their war machine. The Chichimecs organized in raiding parties of 5 to 200 people, and ambushed the supply lines and killed off the livestock, thus effectively slowing down the Spanish, almost to a standstill in some instances. The promise of loot from raids attracted many warriors from faraway tribes, thus ensuring a never-ending and fresh supply of enthusiastic, able-bodied men to fight the Spanish. Chichimec guerilla tactics often turned numerical disadvantages into victories. In one account, outnumbered four to one, some fifty Zacateco fighters attached a contingent of 200 Spanish troops and defeated them. In the early part of the war, the Chichimecs captured Spanish horses and learned to ride them. Because of this, the Chichimec War was the first time the Spanish ever faced mounted indigenous warriors in the New World.

In the 1560s, a full decade into the war, the Spanish started to build fortified settlements in the Gran Chichimeca to establish a permanent military presence to protect mining and agricultural interests. By the 1570s, the Chichimeca War had become costly, and the unrelenting, unstoppable indigenous warriors had put a huge dent in the armor of the Spanish Empire. A letter survives written by the viceroy of New Spain in Mexico City to the king of Spain, Phillip the Second. The letter, dated October 31, 1576, reads:

“We need for some quantity of soldiers to be sent, and to be paid a royal salary as agreed upon by Your Majesty and of which Your Majesty will send to be paid, a third of the Royal Hacienda (in Mexico City), and by the miners and those interested. No one can sustain the war, the cost is too big, neither in arms nor in squadrons can we sustain war. The situation is very crucial, we don’t have weapons, squadrons, food because every day our livestock gets stolen or killed of which sustaining the cattle has been very difficult. We don’t have enough funds to keep the people happy. Everyone agrees that we need support from the royal treasury.”

The Spanish king agreed and sent what was required, but it was not enough.

The Spanish felt worn down by constant road closures, attacks on settlers and mines, and theft of livestock and other resources. Also, members of the clergy who had initially supported the military campaign spoke out against the Spanish policy of war by “fuego y sangre,” or “fire and blood,” which brought death, enslavement or mutilation to captured Chichimec warriors. the Spanish eventually gave in and paid for peace. By the late 1580s the Spanish were forced to pay tribute to the Chichimeca in order to continue with their limited mining operations and to be allowed to live in Chichimec territory unbothered. In 1584, the Bishop of Guadalajara proposed the establishment of new towns in Chichimec territory made up of Spanish civilian settlers and what was then termed as “friendly Indians” from central Mexico. The Viceroy of New Spain, Alvaro Manrique de Zuniga, liked the bishop’s idea, and near the end of the war Spain established new settlements in the north to start the slow process of Chichimec assimilation, which was the beginning of the end of many of the subgroups of Chichimeca.

Today, where are the Chichimeca? What became of these fierce resistors of European expansion? Viceroy Zuniga’s plan of Chichimec assimilation met with great success, from the point of view of the Spanish. Over a 50-year period most of the Chichimeca were assimilated into the mainstream Spanish-based mestizo culture of New Spain. Indians from central Mexico who became part of the new settlements in the north helped Christianize the Chichimecs and serve as examples of “peaceful Indians” to them and intermarried with them. After a century, the northern tribes had all been “washed away” and had become part of everyday colonial Mexican society. Some Chichimeca groups are completely extinct as social and cultural entities. Others moved and kept some of their cultural attributes. Scholars believe that the modern-day Huichol people are the descendants of the Guachichiles and about 20,000 of them live in remote areas of the states of Jalisco and Nayarit. Many Huichol people still speak their native language and hold on to their ancient religious beliefs and practices while being nominally Catholic. Some researchers believe that the Yaquis who now live in the Mexican state of Sonora and the US state of Arizona are descended from one of the original Chichimec groups that migrated to their respective modern-day homelands after the initial Spanish expansion. A group calling itself the Chichimeca Jonaz, numbering about 1,500 people, live in small villages in the state of Guanajuato. They are believed to have been descended from the Pames of the original Chichimeca Confederation. The modern-day reality of the situation is that the Chichicimeca, a once-feared group which dominated the northern area of Mexico, for the most part has been absorbed into the larger mestizo Mexican society. Most modern Mexicans and their descendants with roots in the northern states of Mexico carry the blood of this proud ancient people in their veins, and unknowingly serve as living testimony of a forgotten race.

REFERENCES

Hrdlicka, Ales. The Chichimec and Their Ancient Culture. Sydney: Wentworth Press, 2006.

Buy the book here: https://amzn.to/2UOTRfs

Powell, Phillip Wayne Soldiers, Indians & Silver. Berkeley: U of CA Press, 1952

Buy the book here: https://amzn.to/2XwcH7W

Schaefer, Stacy B. and Furst, Peter T. People of the Peyote: Huichol Indian History, Religion, and Survival, Albuquerque: U of NM Press, 1997

Buy the book here: https://amzn.to/2Xy6Ajr