Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

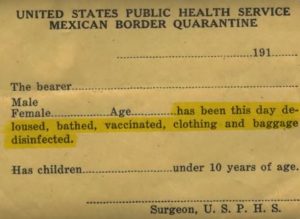

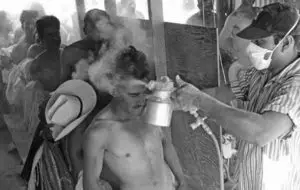

The date was January 28, 1917 and the time was approximately 7:30 in the morning. It was a typical day for Carmelita Torres, a 17-year-old Mexican maid who cleaned houses in El Paso. Carmelita was using the trolley to cross over the Mexican border via the Santa Fe Bridge as she did every morning. This day, however, when a US Customs official boarded the electric streetcar and asked her to get off, the young Mexican maid refused. Carmelita had had enough. She was tired of submitting herself to the humiliation of the delousing process that had become part of her daily routine to enter the US. At the time, all Mexicans entering the United States across the southern border were subjected to this. Men and women were separated into different buildings at the inspection station. Any children present would accompany the women. In these buildings, the customs officials had the Mexicans take off all their clothes and remove all valuables. Clothes and other articles were steamed, and those items that might have been damaged by the steam were exposed to a type of cyanide gas. The officers conducting these strip searches then examined the nude persons for lice. If they found any lice on men, all their hair was cut off and the clippings were burned. If any lice were found on women, the women’s hair was doused with a mixture of kerosene and vinegar, and then wrapped in a towel. Infected women then had to wait 30 minutes until customs officials could conduct a secondary inspection. If any live lice were found after that, the process was repeated. Once people passed the lice inspection, their naked bodies were sprayed with a liquid made of a combination of soap and gasoline. After gathering their belongings and dressing, the Mexicans were vaccinated and given a certificate stating that they had completed the procedure. The certificates were only valid for one week. Rumors circulated among the female border crossers that stripped-down women were being secretly photographed by US Customs officials and those naked photos were being sold and shared in El Paso bars and cantinas across the border in Ciudad Juárez. There was also some legitimate fear among crossers because of what happened the year before in an El Paso prison. 28 inmates died in the gasoline delousing baths when a cigarette ignited bathers. The auburn-haired and resolute Carmelita Torres would not subject herself again to another humiliating disinfecting procedure. When she refused to get off the bus she was told to go back across the border to Mexico. She asked if she could get a refund for the trolley ride. The trolley conductor told her, “no.” Carmelita refused to move.

The date was January 28, 1917 and the time was approximately 7:30 in the morning. It was a typical day for Carmelita Torres, a 17-year-old Mexican maid who cleaned houses in El Paso. Carmelita was using the trolley to cross over the Mexican border via the Santa Fe Bridge as she did every morning. This day, however, when a US Customs official boarded the electric streetcar and asked her to get off, the young Mexican maid refused. Carmelita had had enough. She was tired of submitting herself to the humiliation of the delousing process that had become part of her daily routine to enter the US. At the time, all Mexicans entering the United States across the southern border were subjected to this. Men and women were separated into different buildings at the inspection station. Any children present would accompany the women. In these buildings, the customs officials had the Mexicans take off all their clothes and remove all valuables. Clothes and other articles were steamed, and those items that might have been damaged by the steam were exposed to a type of cyanide gas. The officers conducting these strip searches then examined the nude persons for lice. If they found any lice on men, all their hair was cut off and the clippings were burned. If any lice were found on women, the women’s hair was doused with a mixture of kerosene and vinegar, and then wrapped in a towel. Infected women then had to wait 30 minutes until customs officials could conduct a secondary inspection. If any live lice were found after that, the process was repeated. Once people passed the lice inspection, their naked bodies were sprayed with a liquid made of a combination of soap and gasoline. After gathering their belongings and dressing, the Mexicans were vaccinated and given a certificate stating that they had completed the procedure. The certificates were only valid for one week. Rumors circulated among the female border crossers that stripped-down women were being secretly photographed by US Customs officials and those naked photos were being sold and shared in El Paso bars and cantinas across the border in Ciudad Juárez. There was also some legitimate fear among crossers because of what happened the year before in an El Paso prison. 28 inmates died in the gasoline delousing baths when a cigarette ignited bathers. The auburn-haired and resolute Carmelita Torres would not subject herself again to another humiliating disinfecting procedure. When she refused to get off the bus she was told to go back across the border to Mexico. She asked if she could get a refund for the trolley ride. The trolley conductor told her, “no.” Carmelita refused to move.

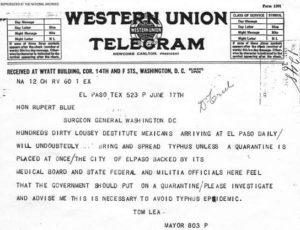

What brought the young Mexican maid to that point? What was behind the whole undignified process at the US-Mexico border? The story begins with fears of a typhus epidemic spreading into the United States from Mexico. During the times of the Mexican Revolution in the 1910s, or “the teens,” with much unrest in Mexico there also came disease and rumors of disease. Typhus had spread from Mexico City to other parts of the country between 1915 and 1917. In the year 1916, over 20 cases of typhus were reported in El Paso, with 3 deaths. Thomas Calloway Lea, the new mayor of El Paso at the time, promised to clean up the city, and that did not just mean getting rid of the ring of dirty and corrupt politicians led by Irish political boss Charles Kelly and his Mexican supporters on both sides of the border. Mayor Lea wanted to do something about the “dirty lousey destitute Mexicans” that he claimed were a scourge on his city. One of his first acts as mayor was to demolish hundreds of adobe homes in the Chihuahuita neighborhood of El Paso. Mayor Lea claimed that these domiciles were, “germ infested.” He accomplished the task of razing the homes with the help of the troops of US General John Pershing, the famous cross-border hunter of Pancho Villa. As an aside, Mayor Thomas Lea had his own Pancho Villa connection. After Villa’s March 9, 1916 raid on Columbus, New Mexico, Lea proclaimed that if Pancho Villa would ever enter El Paso, he would be immediately arrested and tried for his crimes. Pancho Villa’s response was to offer a bounty of a thousand pesos in gold for the head of Mayor Lea. This interesting Pancho Villa story aside, the El Paso mayor’s major concern in his cleanup campaign was preventing the spread of typhus. History records in interviews now stored at the Institute of Oral History at UTEP that Tom Lea even wore silk underwear because a doctor friend of his told him that typhus lice do not stick to silk. Mayor Lea sent cables to Washington DC for months in 1916 arguing for a full quarantine of all Mexicans at the border. He wanted the federal government to construct a special “quarantine camp” to detain all Mexican border crossers for up to 14 days to ensure they were typhus-free before letting them

What brought the young Mexican maid to that point? What was behind the whole undignified process at the US-Mexico border? The story begins with fears of a typhus epidemic spreading into the United States from Mexico. During the times of the Mexican Revolution in the 1910s, or “the teens,” with much unrest in Mexico there also came disease and rumors of disease. Typhus had spread from Mexico City to other parts of the country between 1915 and 1917. In the year 1916, over 20 cases of typhus were reported in El Paso, with 3 deaths. Thomas Calloway Lea, the new mayor of El Paso at the time, promised to clean up the city, and that did not just mean getting rid of the ring of dirty and corrupt politicians led by Irish political boss Charles Kelly and his Mexican supporters on both sides of the border. Mayor Lea wanted to do something about the “dirty lousey destitute Mexicans” that he claimed were a scourge on his city. One of his first acts as mayor was to demolish hundreds of adobe homes in the Chihuahuita neighborhood of El Paso. Mayor Lea claimed that these domiciles were, “germ infested.” He accomplished the task of razing the homes with the help of the troops of US General John Pershing, the famous cross-border hunter of Pancho Villa. As an aside, Mayor Thomas Lea had his own Pancho Villa connection. After Villa’s March 9, 1916 raid on Columbus, New Mexico, Lea proclaimed that if Pancho Villa would ever enter El Paso, he would be immediately arrested and tried for his crimes. Pancho Villa’s response was to offer a bounty of a thousand pesos in gold for the head of Mayor Lea. This interesting Pancho Villa story aside, the El Paso mayor’s major concern in his cleanup campaign was preventing the spread of typhus. History records in interviews now stored at the Institute of Oral History at UTEP that Tom Lea even wore silk underwear because a doctor friend of his told him that typhus lice do not stick to silk. Mayor Lea sent cables to Washington DC for months in 1916 arguing for a full quarantine of all Mexicans at the border. He wanted the federal government to construct a special “quarantine camp” to detain all Mexican border crossers for up to 14 days to ensure they were typhus-free before letting them  into the United States. Mayor Lea even wrote a letter to American President Woodrow Wilson for assistance with this supposed “epidemic.” Cooler heads in Washington believed the El Paso mayor to be overreacting. A boots-on-the ground public health service official stationed in El Paso, Dr. B.J. Lloyd gave this statement to the US Surgeon General at the time, Dr. Rupert Blue:

into the United States. Mayor Lea even wrote a letter to American President Woodrow Wilson for assistance with this supposed “epidemic.” Cooler heads in Washington believed the El Paso mayor to be overreacting. A boots-on-the ground public health service official stationed in El Paso, Dr. B.J. Lloyd gave this statement to the US Surgeon General at the time, Dr. Rupert Blue:

“Typhus fever is not now and probably never will be, a serious menace to our civilian population in the United States. We probably have typhus fever in many of our large cities now. I am opposed to the idea (of quarantine camps at the border) for the reason that the game is not worth the candle.”

Dr. Lloyd played a role as intermediary and somewhat diplomatically suggested setting up delousing facilities instead of quarantine camps. In a letter to his superiors, Dr. Lloyd stated that he was “cheerfully” willing to “bathe and disinfect all the dirty, lousy people who are coming into our country from Mexico.” The mayor of El Paso got less than he wanted, but the disinfecting stations at the border would have to do. He grew to accept them. Carmelita Torres did not.

The day of Carmelita’s refusal to get off the trolley – January 28, 1917 – would mark the beginning of drastic changes affecting the US-Mexico border. The principled young maid sat there on the bus and became angry and vocal. She convinced 30 other women, also housekeepers like her, to refuse the delousing/disease inspection process. Within an hour, more than 200 Mexican women joined Carmelita and blocked all traffic into El Paso from Mexico on the Santa Fe Bridge. By noon, the numbers of protestors swelled to an estimate of “several thousand” according to the Texas press. After shutting down the border for hours, the group marched to the disinfection buildings and tried to get other Mexicans to stop submitting themselves to the humiliating delousing process. US immigration and health officials tried to disburse the crowd, but the protestors became violent and hurled rocks and bottles at the Americans. Although some customs officials sustained minor injuries, the growing mob caused greater concern. The rioters not only worried government workers at the border but as word about the riot spread throughout the city, El Paso citizens demanded that more be done. General Bell, the commander of Fort Bliss, ordered his soldiers to confront the thousands of angry people. The soldiers were pelted with rocks and jeered  at. Carmelita Torres was in the center of the fray, as were the original women from the trolley. Newspapers referred to them as “The Amazons.” There was no indication that the thousands of protestors were going to back down. Some of the stories of what happened next are very detailed in press accounts. A group of rioters lay down on the trolley tracks while another group took over the trolleys themselves. A reporter on the scene noted that 3 Mexican maids threw out the trolley conductor and tried to cling to him to prevent him from escaping. One of the women gave him a black eye. Another trolley conductor fled across to the border, pursued by a small group of women, and hid out in a Chinese restaurant on Avenida Juárez until the coast was clear. The Mexican Consul General in El Paso, Andrés García, tried to meet with protestors in the middle of the bridge, but the mob surrounded his car and prevented it from moving. García quieted the rioters for a brief time, but by the end of the afternoon hundreds more joined in the struggle.

at. Carmelita Torres was in the center of the fray, as were the original women from the trolley. Newspapers referred to them as “The Amazons.” There was no indication that the thousands of protestors were going to back down. Some of the stories of what happened next are very detailed in press accounts. A group of rioters lay down on the trolley tracks while another group took over the trolleys themselves. A reporter on the scene noted that 3 Mexican maids threw out the trolley conductor and tried to cling to him to prevent him from escaping. One of the women gave him a black eye. Another trolley conductor fled across to the border, pursued by a small group of women, and hid out in a Chinese restaurant on Avenida Juárez until the coast was clear. The Mexican Consul General in El Paso, Andrés García, tried to meet with protestors in the middle of the bridge, but the mob surrounded his car and prevented it from moving. García quieted the rioters for a brief time, but by the end of the afternoon hundreds more joined in the struggle.

Rioting continued the next day, January 29th, and by then most of the demonstrators were men. Many joined the riots because they saw it as an opportunity to protest the regime of Mexican president Venustiano Carranza. The Mexican Revolution was still fresh in their minds, and many in the north of Mexico had supported Pancho Villa over Carranza. The Mexican authorities recognized the anti-Carranza elements in the protests as severe threats, and Ciudad Juárez’ Chief of Police, Maximo Torres, gave the order that all rioters were to be arrested. A Mexican general loyal to the Carranza regime named Francisco Murguía led his cavalry to try to quell the riot. General Murguía’s troops with their skull and crossbones insignia, were known as El Esquadrón de la Muerte, or “The Squadron of Death,” in English. The protestors refused to be intimidated, even with the Mexican cavalry brandishing their sabers, and continued to hurl rocks and insults at authority. The conflict intensified and rumors circulated that one of the female protestors had been shot. The Ciudad Juárez Chief of Police denied this. By this second day, business owners and households on the El Paso side began to feel the impact of the protests as they were lacking labor. They asked the El Paso Chamber of Commerce to resolve the issue. The protests had inspired others on the Mexican side not directly involved in the riots to stay home and not cross the border to come to work. El Paso was starting to feel the consequences of Mayor Lea’s need to “clean up the city.”

The riots continued on January 30 and that’s when formal arrests began. One woman and two men were taken into custody on the American side for attacking a customs official and a US army infantryman. Protests sprung up spontaneously in Ciudad Juárez, but the sentiments of the disgruntled Mexicans were divided among support for the women, support for Pancho Villa and a general condemnation of the US. Local police made arrests. The riots ended on both sides of the border when US officials waived some of the bath requirements, notably, by accepting certificates from Mexican doctors declaring border crossers free of typhus. It was ultimately up to the discretion of the American border agents to make the final determination on whether the person crossing was okay to be admitted to the US or if they needed a bath despite their Mexican paperwork.

The riots continued on January 30 and that’s when formal arrests began. One woman and two men were taken into custody on the American side for attacking a customs official and a US army infantryman. Protests sprung up spontaneously in Ciudad Juárez, but the sentiments of the disgruntled Mexicans were divided among support for the women, support for Pancho Villa and a general condemnation of the US. Local police made arrests. The riots ended on both sides of the border when US officials waived some of the bath requirements, notably, by accepting certificates from Mexican doctors declaring border crossers free of typhus. It was ultimately up to the discretion of the American border agents to make the final determination on whether the person crossing was okay to be admitted to the US or if they needed a bath despite their Mexican paperwork.

Some scholars who studied the 1917 Bath Riots claim that Carmelita Torres was the “Latina Rosa Parks.” Although heroic, this young maid’s actions at the border and the protests she inspired did little to change things. In fact, the entrance requirements became more severe and never went back to pre-Mayor-Lea days when entering the US was relatively easy. The Immigration Act of 1917 – passed just days after the riots – imposed taxes on people entering the US from Mexico and forced Mexican workers to take literacy tests. The new law also prohibited Mexicans from performing contract labor. Business owners throughout the American Southwest petitioned Congress to exempt Mexicans from paying the tax. This was eventually lifted after the US entered World War I and the need for Mexican labor was high. The forced baths and fumigation – which used DDT and Zyklon-B – lasted until the 1950s. What started with one man’s fear of a possible pandemic had long-lasting effects and helped forge later policies of increased governmental control at the southern US border. And whatever became of Carmelita Torres? This woman whom the newspapers once dubbed “the red-haired Amazon” seems to be lost to history.

REFERENCES

Dorado Romo, David. Ringside Seat to a Revolution. El Paso: Cinco Puntos Press, 2005. We are an Amazon affiliate. Get the book on Amazon here: https://amzn.to/2IRg301

“Mexican Rioters Attack US Troops: 200 Women Lead in Assault at Bridge.” El Paso Herald. 21 Jan 1917, p. 1.