Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

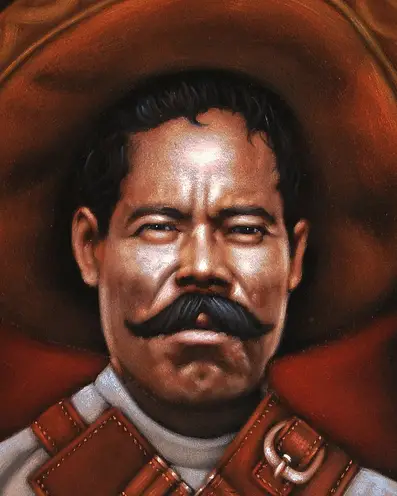

Pancho Villa, a towering figure of the Mexican Revolution, was as much a man of passion as he was a warrior. Born Doroteo Arango in 1878 in San Juan del Río, Durango, Villa transformed from a fugitive bandit into a revolutionary icon, leading the Division of the North with daring raids and charismatic defiance. His 1916 attack on Columbus, New Mexico, and his battles against Mexican elites made him a folk hero, celebrated in corridos and feared by enemies. Yet, Villa’s personal life was as chaotic as the revolution he championed, marked by a web of marriages, mistresses, and myths. Historical accounts suggest he had anywhere from 23 to 75 “wives,” though only one marriage was legally recognized by the Catholic Church and the Mexican government. These relationships, often strategic or fleeting, reflect the turbulence of his era, blending love, loyalty, and betrayal. This article explores Villa’s documented wives and notable mistresses, the dramatic “Battle of the Widows” after his 1923 assassination, and the enduring mystery of his romantic entanglements, offering a glimpse into the heart of a legend whose loves were as untamed as his revolution.

Pancho Villa, a towering figure of the Mexican Revolution, was as much a man of passion as he was a warrior. Born Doroteo Arango in 1878 in San Juan del Río, Durango, Villa transformed from a fugitive bandit into a revolutionary icon, leading the Division of the North with daring raids and charismatic defiance. His 1916 attack on Columbus, New Mexico, and his battles against Mexican elites made him a folk hero, celebrated in corridos and feared by enemies. Yet, Villa’s personal life was as chaotic as the revolution he championed, marked by a web of marriages, mistresses, and myths. Historical accounts suggest he had anywhere from 23 to 75 “wives,” though only one marriage was legally recognized by the Catholic Church and the Mexican government. These relationships, often strategic or fleeting, reflect the turbulence of his era, blending love, loyalty, and betrayal. This article explores Villa’s documented wives and notable mistresses, the dramatic “Battle of the Widows” after his 1923 assassination, and the enduring mystery of his romantic entanglements, offering a glimpse into the heart of a legend whose loves were as untamed as his revolution.

Villa’s life was a saga of reinvention. At 16, he fled his home after killing a man who assaulted his sister, embarking on a bandit career that honed his guerrilla tactics. By 1910, as the Mexican Revolution erupted against Porfirio Díaz’s regime, at age 32 Villa emerged as a leader, his cavalry raids striking fear into the hearts of oppressors. His charisma and audacity made him a symbol of resistance, but his personal life was equally bold. Historians estimate he married at least 23 women, most in informal ceremonies, though some claim the number reached 75. These unions, often undocumented, were partly strategic, securing alliances with families or loyalty among followers in a fractured nation. The lack of records, combined with Villa’s larger-than-life persona, has shrouded his romantic life in mystery, making it a compelling lens through which to explore his legacy.

Villa’s loves spanned devoted partners, transient companions, and a glamorous actress who famously rebuffed him. His legal wife, María Luz Corral, anchored his life, while others, like Soledad Seañez and Austreberta Rentería, clashed over his estate in the “Battle of the Widows.” Mistresses, such as María Conesa, added intrigue, and fictionalized figures like María Flores fueled Villa’s mythos. The uncertainty around his wives—23? 75?—and the contested legacy of his death amplify the enigma. This narrative, rich with drama, invites us to unravel the women who shaped Villa’s life and the revolution that framed their stories. Here are some of the main ones:

María Luz Corral 1872–1981

María Luz Corral 1872–1981

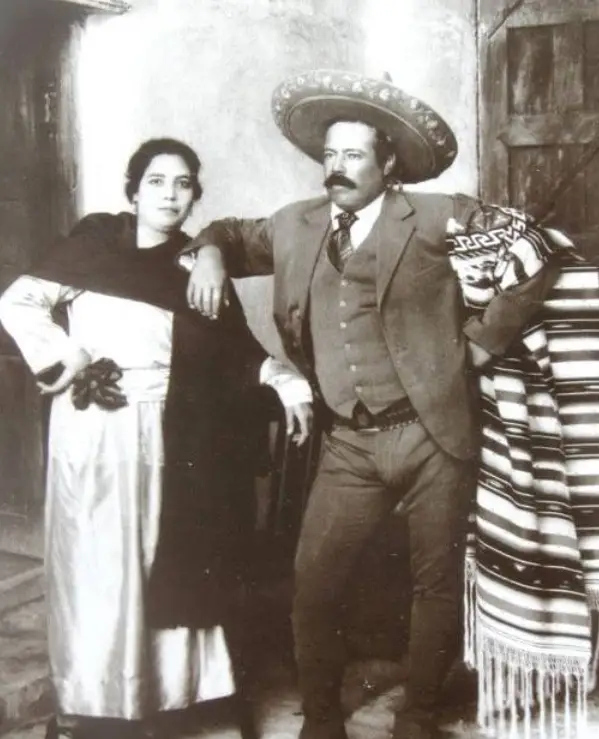

María Luz Corral, born in Chihuahua, was Villa’s only legally recognized wife, marrying him in a formal ceremony on May 29, 1911, at the height of the Mexican Revolution. A devout Catholic from a modest family, Luz was known for her resilience, managing Villa’s household and supporting his campaigns despite his frequent absences and infidelity. She bore no surviving children with Villa but raised his daughter from another relationship, cementing her role as a maternal figure. After Villa’s assassination in 1923, Luz dedicated her life to preserving his memory, transforming their Chihuahua home into a museum filled with his artifacts, including his bullet-riddled car. Her unwavering loyalty, despite Villa’s many loves, makes her a central figure in his saga, a woman who guarded his legacy through decades of solitude.

Juana Torres – Dates Unknown

Juana Torres, a shadowy figure from Villa’s pre-revolutionary days, is said to have married him in an informal ceremony during his bandit years in Durango. Likely from a rural community, Juana may have been a companion during his early flights from justice, sharing the hardships of his outlaw life. Little is documented about her, and her fate remains unknown, possibly lost to the chaos of Villa’s rising fame. Her obscurity highlights the transient nature of Villa’s early relationships, where women often faded into the background as his revolutionary star ascended, leaving only whispers of their bond.

Soledad Seañez – Dates Unknown

Soledad Seañez, born in northern Mexico, claimed to be Villa’s wife and emerged as a key figure in the “Battle of the Widows” after his 1923 assassination. Likely a partner during his revolutionary campaigns, Soledad may have been a camp follower or soldadera, women who traveled with armies, cooking and caring for soldiers. Her claim to Villa’s estate, including properties in Chihuahua, suggests a significant relationship, though she lacked any legal documentation. Soledad’s rivalry with Luz Corral and Austreberta Rentería was fierce, reflecting the emotional and financial stakes of Villa’s legacy. Her story underscores the contested nature of his loves, as she fought to secure her place in his history.

Austreberta Rentería – Dates Unknown

Austreberta Rentería – Dates Unknown

Austreberta Rentería, another claimant to Villa’s spousal title, was likely a partner from his later revolutionary years, possibly in Chihuahua or Durango. Born into a working-class family, Austreberta may have met Villa during one of his campaigns, forming a bond amid the upheaval of war. After his death, she joined the “Battle of the Widows,” seeking a share of his estate and later receiving a modest pension from the Mexican government, indicating official recognition of her claim. Her persistence, despite limited success, reveals the complex web of Villa’s relationships, where love and legitimacy were often blurred by the revolution’s chaos.

Paula Alamillo – Dates Unknown

Paula Alamillo, mentioned in some accounts as a wife during Villa’s revolutionary peak, likely hailed from a northern Mexican community tied to his campaigns. As a possible soldadera or local ally, Paula may have supported Villa’s troops, managing supplies or forging community ties. Her relationship with Villa, though poorly documented, suggests a partnership rooted in the revolution’s demands, where personal and political bonds intertwined. Her story reflects the unsung roles of women who sustained Villa’s efforts, their lives shaped by the transient camps and constant danger of his army.

Esther Cardona – Dates Unknown

Esther Cardona, another reported wife, remains an elusive figure, with minimal historical detail beyond her name and claimed connection to Villa. Likely a partner from his revolutionary years, Esther may have been a young woman from a rural town, drawn to Villa’s charisma or caught in the revolution’s orbit. The scarcity of records about her underscores the fleeting nature of many of Villa’s unions, where women entered and exited his life amid the whirlwind of war. Her presence in his story hints at countless untold tales, lost to history’s gaps.

María Barraza – Dates Unknown

María Barraza – Dates Unknown

María Barraza, cited as a wife during Villa’s revolutionary campaigns, was likely a woman from Chihuahua or a neighboring state, possibly a supporter of his cause. As a potential camp follower, María may have shared the nomadic life of Villa’s army, enduring the hardships of travel and battle. Her relationship with Villa, though undocumented in detail, reflects the transient bonds formed in revolutionary camps, where love was as fleeting as victory. Her story adds depth to the tapestry of Villa’s loves, a reminder of the women who lived in his shadow.

María Conesa – 1892–1978

María Conesa, born in Spain and raised in Mexico, was a celebrated actress and singer known as “La Gatita Blanca,” a star of Mexico City’s theater scene. In 1914, during a performance, she reportedly caught Villa’s eye, his revolutionary fame at its peak. Smitten, Villa offered her a night of passion, but Conesa, with sharp wit, retorted, “I’m not one of your soldaderas,” rebuffing him in a moment that became legendary. Her defiance, rooted in her independent spirit and artistic prominence, adds a glamorous chapter to Villa’s romantic saga, highlighting his allure and the women who resisted it.

María Flores – Fictionalized

María Flores was a cantina owner found in romanticized tales of Villa’s youth and in campfire songs sung about the future revolutionary and his many loves. María is likely a fictional figure, said to have inspired his revolutionary zeal after her tragic death at the hands of a wealthy local hacienda owner. In these stories and songs, she was a fiery, independent woman from Durango, whose love for Villa sparked his hatred of injustice. Though not historically verified, her tale reflects the myth-making around Villa’s loves, where fictional women became symbols of his revolutionary passion, adding a layer of folklore to his legacy.

Villa’s assassination on July 20, 1923, in Parral, Chihuahua, ended his revolutionary journey but sparked a new conflict: the “Battle of the Widows.” Luz Corral, Soledad Seañez, and Austreberta Rentería each claimed to be his rightful widow, competing for control of his estate, which included properties, valuables, pensions, and revolutionary honors. Luz, with her legal marriage, emerged as the primary guardian of Villa’s legacy, her museum a testament to her devotion. Soledad and Austreberta, though less successful, secured minor pensions from the Mexican government, their claims revealing the tangled nature of Villa’s relationships. This struggle, fraught with legal battles and personal rivalries, mirrors the revolution’s chaos, a fitting climax to Villa’s romantic saga.

Villa’s assassination on July 20, 1923, in Parral, Chihuahua, ended his revolutionary journey but sparked a new conflict: the “Battle of the Widows.” Luz Corral, Soledad Seañez, and Austreberta Rentería each claimed to be his rightful widow, competing for control of his estate, which included properties, valuables, pensions, and revolutionary honors. Luz, with her legal marriage, emerged as the primary guardian of Villa’s legacy, her museum a testament to her devotion. Soledad and Austreberta, though less successful, secured minor pensions from the Mexican government, their claims revealing the tangled nature of Villa’s relationships. This struggle, fraught with legal battles and personal rivalries, mirrors the revolution’s chaos, a fitting climax to Villa’s romantic saga.

The question of how many wives Villa had—23? 75?—remains a historical enigma. Mainstream historians usually agree to a conservative 23 unions, most informal, while sensationalized accounts inflate the number to around 75. The lack of documentation, coupled with the revolution’s fluid social norms, where legal marriage was often secondary to survival, fuels speculation. Many “wives” were likely mistresses or strategic partners, their bonds sealed by necessity rather than law. This uncertainty, a hallmark of Villa’s mythos, invites us to question whether his charisma drew dozens of women or if his enemies exaggerated his exploits to paint him as a reckless womanizer. The truth, buried in the revolution’s dust, remains elusive.

Pancho Villa’s many loves—documented, rumored, and mythologized—offer a window into a revolutionary whose heart was as bold as his battles. From Luz Corral’s steadfast devotion to María Conesa’s witty defiance, from the “Battle of the Widows” to the mystery of 23 or 75 wives, Villa’s romantic life is a tapestry of passion, strategy, and enigma. These women—wives, mistresses, and myths—shaped his legacy, their stories intertwined with the Mexican Revolution’s chaos. As we ponder the truth behind Villa’s loves, we’re reminded that some legends, like love itself, defy explanation, leaving us to marvel at a man whose heart burned as fiercely as his cause.

REFERENCES

McLynn, Frank. 2008. Villa and Zapata: A History of the Mexican Revolution. New York: Basic Books.

Minster, Christopher. 2023. “Facts About Mexican Leader Pancho Villa.” ThoughtCo, April 5, 2023.