Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

The year was 1537. It’s barely 16 years since Hernán Cortés toppled the Aztec Empire. Mexico City, once the glittering Tenochtitlán, is now a Spanish stronghold, its streets buzzing with European colonists, indigenous laborers, and a new group: enslaved Africans brought by the thousands to work mines and fields. Tensions simmer. The Spanish are brutal overlords, smallpox ravages the land, and whispers of rebellion stir. In the heart of this chaos, a group of Africans and indigenous allies—Aztecs and Tlaxcalans—plot a daring uprising to overthrow their colonizers and carve out a free life in the mountains. Their story, etched into the Codex Telleriano-Remensis, a stunning 16th-century manuscript drawn by indigenous artists, captures a moment when two oppressed groups joined forces against a common enemy. This isn’t just a footnote in history; it’s a tale of courage, betrayal, and defiance that echoes through Mexico’s soul. Many modern-day Mexicans have not even heard of this important event in the formative years of their history. Why did these rebels risk everything? What drove Africans, fresh from the horrors of the slave trade, to align with Aztecs still reeling from conquest? And how does a single page in a codex, delicately illustrated by native hands, tell their story?

The year was 1537. It’s barely 16 years since Hernán Cortés toppled the Aztec Empire. Mexico City, once the glittering Tenochtitlán, is now a Spanish stronghold, its streets buzzing with European colonists, indigenous laborers, and a new group: enslaved Africans brought by the thousands to work mines and fields. Tensions simmer. The Spanish are brutal overlords, smallpox ravages the land, and whispers of rebellion stir. In the heart of this chaos, a group of Africans and indigenous allies—Aztecs and Tlaxcalans—plot a daring uprising to overthrow their colonizers and carve out a free life in the mountains. Their story, etched into the Codex Telleriano-Remensis, a stunning 16th-century manuscript drawn by indigenous artists, captures a moment when two oppressed groups joined forces against a common enemy. This isn’t just a footnote in history; it’s a tale of courage, betrayal, and defiance that echoes through Mexico’s soul. Many modern-day Mexicans have not even heard of this important event in the formative years of their history. Why did these rebels risk everything? What drove Africans, fresh from the horrors of the slave trade, to align with Aztecs still reeling from conquest? And how does a single page in a codex, delicately illustrated by native hands, tell their story?

To understand the uprising, we need to step back into 1537 New Spain. The Aztec Empire fell in 1521, its civic-ceremonial center destroyed with its  grand temples razed, replaced by Spanish churches and administrative buildings of the new regime. Mexico City, built on Tenochtitlán’s ruins, was a colonial hub with dusty streets, wooden crosses, and Spanish haciendas sprawling over formerly indigenous lands. The Spanish enforced a brutal system: encomiendas forced indigenous people of various nations into labor, paying heavy tribute in maize and cloth. Smallpox, sweeping through in waves from the 1520s to the 1540s, killed up to 90% of the indigenous population, leaving survivors bitter and broken. “The air was thick with grief,” wrote an anonymous Aztec scribe in the Codex Telleriano-Remensis, a manuscript blending indigenous Mexican history with colonial realities.

grand temples razed, replaced by Spanish churches and administrative buildings of the new regime. Mexico City, built on Tenochtitlán’s ruins, was a colonial hub with dusty streets, wooden crosses, and Spanish haciendas sprawling over formerly indigenous lands. The Spanish enforced a brutal system: encomiendas forced indigenous people of various nations into labor, paying heavy tribute in maize and cloth. Smallpox, sweeping through in waves from the 1520s to the 1540s, killed up to 90% of the indigenous population, leaving survivors bitter and broken. “The air was thick with grief,” wrote an anonymous Aztec scribe in the Codex Telleriano-Remensis, a manuscript blending indigenous Mexican history with colonial realities.

Enter the Africans. By 1537, the Spanish had imported over 200,000 enslaved people from West Africa in what is now Senegal, Angola and the Congo, via Seville and their Caribbean colonies to work in mines, plantations, and homes. Unlike indigenous laborers, Africans faced lifelong bondage, branded and chained, their lives sometimes valued less than livestock. Yet they weren’t alone in their

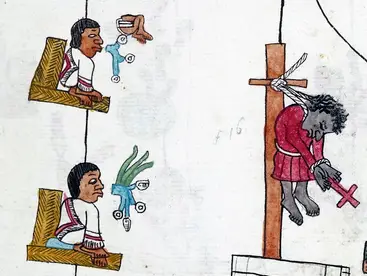

Enter the Africans. By 1537, the Spanish had imported over 200,000 enslaved people from West Africa in what is now Senegal, Angola and the Congo, via Seville and their Caribbean colonies to work in mines, plantations, and homes. Unlike indigenous laborers, Africans faced lifelong bondage, branded and chained, their lives sometimes valued less than livestock. Yet they weren’t alone in their  suffering. Tlaxcalans, once Aztec rivals who allied with Cortés, now faced Spanish taxes and abuse. Shared oppression sparked unlikely bonds: Africans and indigenous people swapped stories of freedom in markets, whispered escape plans in fields. “They understood each other’s chains,” a Spanish chronicler noted, hinting at alliances forming in the shadows. The Codex Telleriano-Remensis, created in the 1550s by Aztec scribes under the supervision of European friars, captures this world. Its 50 folios mix ancient Mesoamerican calendars with colonial events, painted in vibrant reds, blues, and blacks. Folio 45-V, our key to the uprising, shows Africans drawn with darkened skin and curly hair wielding spears alongside proud native warriors in feathered headdresses, facing armored Spaniards. The codex isn’t just art; it’s indigenous testimony, blending Mesoamerican glyphs with European script to record a fractured world. By 1537, New Spain was a tinderbox with disease, exploitation, and cultural clashes fueling rebellion.

suffering. Tlaxcalans, once Aztec rivals who allied with Cortés, now faced Spanish taxes and abuse. Shared oppression sparked unlikely bonds: Africans and indigenous people swapped stories of freedom in markets, whispered escape plans in fields. “They understood each other’s chains,” a Spanish chronicler noted, hinting at alliances forming in the shadows. The Codex Telleriano-Remensis, created in the 1550s by Aztec scribes under the supervision of European friars, captures this world. Its 50 folios mix ancient Mesoamerican calendars with colonial events, painted in vibrant reds, blues, and blacks. Folio 45-V, our key to the uprising, shows Africans drawn with darkened skin and curly hair wielding spears alongside proud native warriors in feathered headdresses, facing armored Spaniards. The codex isn’t just art; it’s indigenous testimony, blending Mesoamerican glyphs with European script to record a fractured world. By 1537, New Spain was a tinderbox with disease, exploitation, and cultural clashes fueling rebellion.

In October 1537, Mexico City’s relative calm was shattered. A group of 20 to 30 enslaved Africans, led by a man described as a “king” in Spanish accounts, hatched a bold plan. Joined by indigenous allies, likely Tlaxcalans and Aztecs, they aimed to kill their Spanish masters, burn haciendas, and flee to the rugged hills west of the city to build a free community. “They wanted a life beyond chains,” wrote Bernardino de Sahagún, a Spanish friar who chronicled life in Mexico in the decades immediately after the conquest. The rebels armed themselves with stolen knives, machetes, and makeshift spears, their resolve forged in shared suffering. The uprising began under cover of night. The rebels struck haciendas and small ranchos on the city’s outskirts, setting fires that lit up the sky. They killed several overseers—Spanish men who’d grown fat on forced labor—looting supplies and rallying others to join. The Codex Telleriano-Remensis paints the scene vividly: Africans with raised spears, their faces fierce, stand beside native warriors in traditional feathered gear, clashing with Spaniards on horseback. The codex’s indigenous artists, working under Spanish oversight, used black skin not as a slur but as a nod to Aztec reverence for dark hues, linked to gods like Tezcatlipoca and Tlaloc. The image in the codex captures chaos, showing flames, blood, and passionate defiance. The rebels’ plan was audacious: completely overthrow the Spanish government, seize Mexico City, and establish a mountain stronghold that would attract others and would grow over time. Africans brought tactics from their homelands, such as guerrilla raids seen in Angola’s wars, while Aztecs and Tlaxcalans knew the terrain, guiding escape routes through volcanic hills. For a moment, it all seemed possible. Spanish sentinels, caught off guard, scrambled to respond. “The city trembled,” Sahagún wrote, noting panic among European residents who feared a full-scale revolt. However, betrayal struck. An African slave, loyal to his Spanish master or coerced by fear, tipped off royal authorities. Spanish forces, armed with swords and attack dogs, hunted the rebels. The pursuit was brutal: dogs tore through the hills, and the captured rebels faced torture. The leaders, including the African “king” whose name has been lost to history, were hanged in Mexico City’s main plaza as a grim warning to others. The codex doesn’t show the mass executions but leaves modern viewers with a lone image of an African man clutching a cross hanging at the gallows. The codex’s stark lines and illustrations of spears broken and warriors fallen, hint at the high cost paid by rebels. The uprising failed, but its spark lingered, and a whisper of freedom spread quietly across the Spanish territories.

The 1537 uprising was crushed, but it wasn’t forgotten. Spanish authorities tightened control, banning Africans and indigenous people from gathering in markets, fearing more plots. Yet the rebellion planted seeds for later resistance. By 1609, a former African slave named Yanga founded a free African community in Veracruz, a maroon settlement that eventually won legal recognition from Spain. For more information about Gaspar Yanga’s slave revolt, please see Mexico Unexplained episode number 159. These early rebels showed that freedom wasn’t just a dream; it was a fight worth waging. The Codex Telleriano-Remensis, now housed in Paris’s Bibliothèque Nationale de France, remains a testament to this moment. Its folio 45-v, just 21 by 30 centimeters, captures a rare view: indigenous artists documenting African and native resistance, not just Spanish triumph. The codex blends Aztec glyphs – notably day signs and gods – with European ink, a hybrid cry in this newly blending world. It’s a reminder that the conquered wrote their own history, preserving stories the Spanish tried to erase. Today, many in Mexico’s Afro-Mexican communities, recognized in the 2021 census, trace their roots to these early rebels, but many so-called “mestizo” Mexicans unknowingly carry in themselves the blood of these revolutionaries as over the centuries the original African slave population became absorbed by the mainstream Mexican gene pool. The 1537 uprising, though small, showed Africans and indigenous people could unite against a common foe, setting the stage for centuries of resistance. In Mexico City’s streets, where haciendas once burned, their courage echoes across time.

The 1537 uprising was crushed, but it wasn’t forgotten. Spanish authorities tightened control, banning Africans and indigenous people from gathering in markets, fearing more plots. Yet the rebellion planted seeds for later resistance. By 1609, a former African slave named Yanga founded a free African community in Veracruz, a maroon settlement that eventually won legal recognition from Spain. For more information about Gaspar Yanga’s slave revolt, please see Mexico Unexplained episode number 159. These early rebels showed that freedom wasn’t just a dream; it was a fight worth waging. The Codex Telleriano-Remensis, now housed in Paris’s Bibliothèque Nationale de France, remains a testament to this moment. Its folio 45-v, just 21 by 30 centimeters, captures a rare view: indigenous artists documenting African and native resistance, not just Spanish triumph. The codex blends Aztec glyphs – notably day signs and gods – with European ink, a hybrid cry in this newly blending world. It’s a reminder that the conquered wrote their own history, preserving stories the Spanish tried to erase. Today, many in Mexico’s Afro-Mexican communities, recognized in the 2021 census, trace their roots to these early rebels, but many so-called “mestizo” Mexicans unknowingly carry in themselves the blood of these revolutionaries as over the centuries the original African slave population became absorbed by the mainstream Mexican gene pool. The 1537 uprising, though small, showed Africans and indigenous people could unite against a common foe, setting the stage for centuries of resistance. In Mexico City’s streets, where haciendas once burned, their courage echoes across time.

The 1537 uprising wasn’t just a failed revolt; it was a bold stand by Africans and indigenous peoples against impossible odds. In a world torn by conquest, injustice and disease, they dared to dream of freedom, wielding knives and spears under a moonlit sky. The Codex Telleriano-Remensis, with its vivid folio 45-v, freezes their defiance with its blackened figures and feathered warriors fighting side by side. This isn’t a ghost story or a dusty archive; it’s a living piece of Mexico’s soul, a reminder that resistance runs deep. The rebels lost, but their legacy endures in maroon communities, in the codex’s ink, in Mexico’s diverse heartbeat. As we uncover these forgotten stories, we ask: what other alliances shaped this land? Mexico has much hidden history that has yet to see the light of day.

REFERENCES