The date was June 16, 2015 and the place was New York City. Americans were glued to their television sets and were captivated when they saw a man familiar to everyone making an interesting proclamation:

The date was June 16, 2015 and the place was New York City. Americans were glued to their television sets and were captivated when they saw a man familiar to everyone making an interesting proclamation:

“I will build a great wall – and nobody builds walls better than me, believe me – and I build them very inexpensively. I will build a great, great wall on our southern border, and I will make Mexico pay for that wall. Mark my words.”

The person uttering those words was billionaire Donald J. Trump in his speech made to announce his candidacy for the office of President of the United States of America. The future president outlined the reasons for this “great, great wall,” and almost immediately Americans were divided about what they thought of Trump’s proposition. Those living outside the Southwestern United States and those who have never crossed the border into Mexico by land were unaware that a wall had already existed on parts of America’s southern border for many years in one form or another, and that construction of the first border wall began in 1918 after a bloody battle involving American and Mexican troops in what has been termed by historians as The Border Wars which lasted from 1910 to 1919.

Skirmishes and small raids coming from both sides of the border date back to the time the borders between the United States and Mexico were first drawn after the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848 which ceded most of what is now the American Southwest to the United States. With the crumbling of the Porfirio Díaz regime in Mexico in the early part of the 20th Century and revolutionary sentiment stirring in that country, by 1910 the US government saw the need to send Army troops to American border towns to help protect lives and property and to make sure fighting between Mexican government troops and rebel forces stayed on the southern side of the line. In October of 1910, from his safe haven in San Antonio, Texas, exiled political leader Francisco Madero issued the Plan of San Luís Potosí declaring the 1910 re-election of Porfirio Díaz null and void and calling all Mexicans to rise up against the Díaz government. In the plan Madero declared himself the legitimate president of Mexico. On November 20, 1910 Madero planned a raid across the Rio Grande to attack Ciudad Porfiro Díaz in the Mexican state of Coahuila, but because less than a dozen men showed up to accompany him, Madero retreated to New Orleans to formulate another plan of attack. After the failed raid, Mexican president Porfirio Díaz pressured the US government to extradite Madero and by February of 1911 he managed to elude American forces and slipped back into Mexico.

Skirmishes and small raids coming from both sides of the border date back to the time the borders between the United States and Mexico were first drawn after the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848 which ceded most of what is now the American Southwest to the United States. With the crumbling of the Porfirio Díaz regime in Mexico in the early part of the 20th Century and revolutionary sentiment stirring in that country, by 1910 the US government saw the need to send Army troops to American border towns to help protect lives and property and to make sure fighting between Mexican government troops and rebel forces stayed on the southern side of the line. In October of 1910, from his safe haven in San Antonio, Texas, exiled political leader Francisco Madero issued the Plan of San Luís Potosí declaring the 1910 re-election of Porfirio Díaz null and void and calling all Mexicans to rise up against the Díaz government. In the plan Madero declared himself the legitimate president of Mexico. On November 20, 1910 Madero planned a raid across the Rio Grande to attack Ciudad Porfiro Díaz in the Mexican state of Coahuila, but because less than a dozen men showed up to accompany him, Madero retreated to New Orleans to formulate another plan of attack. After the failed raid, Mexican president Porfirio Díaz pressured the US government to extradite Madero and by February of 1911 he managed to elude American forces and slipped back into Mexico.

Meanwhile, the magonistas – followers of the anarcho-communist school of thought proposed by Mexican dissident Ricardo Flores Magón – began campaigning in the border areas of Baja California, even capturing Mexicali on February 11, 1911. The magonistas marched to Tijuana, took over the federal garrison there and were eventually chased to the American side of the border at San Ysidro, California a few months later. In California the magonistas gathered arms and prepared for future incursions to fight with federal troops. While the magonistas were in control of Tijuana,  Francisco Madero led over 120 men to attack Mexican federal forces at Casas Grandes in northern Chihuahua. The Madero forces were defeated in the battle but the federales retreated south leaving Madero in control. Madero’s rebel army got frequent supplies of arms from those sympathetic to their cause north of the border. In their first engagement with American troops on US soil, the Madero group attacked Douglas, Arizona after defeating the federal troops on the Mexican side at Agua Prieta, Sonora. While the US forces pushed the rebels back across the border, the rebels still had control over Agua Prieta. There were also two major instances of fighting in and around Ciudad Juárez in the spring of 1911. The first instance involved the sabotage of the military barracks in March and the theft of the cannon from the middle of El Paso’s town square on the American side of the border. The second Battle of Ciudad Juárez happened from April 7th to May 10th 1911 and involved the American garrison at El Paso which exchanged fire with rebels led by Madero supporter Pancho Villa in his first major battle. The Americans suffered minor casualties. Later that year Porfirio Díaz went into exile in Europe, Madero assumed the presidency of Mexico and warfare briefly ceased along the border, that is, until fighting started among the rebel factions.

Francisco Madero led over 120 men to attack Mexican federal forces at Casas Grandes in northern Chihuahua. The Madero forces were defeated in the battle but the federales retreated south leaving Madero in control. Madero’s rebel army got frequent supplies of arms from those sympathetic to their cause north of the border. In their first engagement with American troops on US soil, the Madero group attacked Douglas, Arizona after defeating the federal troops on the Mexican side at Agua Prieta, Sonora. While the US forces pushed the rebels back across the border, the rebels still had control over Agua Prieta. There were also two major instances of fighting in and around Ciudad Juárez in the spring of 1911. The first instance involved the sabotage of the military barracks in March and the theft of the cannon from the middle of El Paso’s town square on the American side of the border. The second Battle of Ciudad Juárez happened from April 7th to May 10th 1911 and involved the American garrison at El Paso which exchanged fire with rebels led by Madero supporter Pancho Villa in his first major battle. The Americans suffered minor casualties. Later that year Porfirio Díaz went into exile in Europe, Madero assumed the presidency of Mexico and warfare briefly ceased along the border, that is, until fighting started among the rebel factions.

Although president of Mexico in 1912, Madero had a tenuous hold over the country. His former military leaders who helped him rebel against the government, notably Pancho Villa and Pasqual Orozco, turned against him and fomented unrest in the north. Madero decided to establish Fort Tijuana on the border with the United States just south of San Diego to retake the area from the anarcho-communist rebels. By 1913 the Mexican Revolution in the north began ramping up. A rebel army of 2,000 led by General Obregón attacked Nogales, Sonora, a border town with a sister city on the US side in Arizona. They defeated the federal forces in the town with some of the fighting spilling over into the American side. By mid-1913 the Americans began construction of 12 army forts to help protect Americans from this spillover of fighting from quarreling Mexican rebel groups and federales.

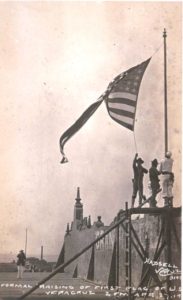

By early 1914 Mexican relations with the United States had almost reached the breaking point. In April of that year a group of US Navy sailors who were purchasing fuel in the Mexican port city of Tampico were detained by Mexican officials and the US government demanded an apology from the government of Victoriano Huerta, the man who overthrew Madero the year before. The Huerta government refused to comply with certain elements of the demanded apology, so President Woodrow Wilson asked for congressional approval for an armed intervention in Mexico. The port city of Veracruz was taken over by US troops as a result, and the Americans left in November of 1914 after a 7-month occupation. While the Americans occupied Veracruz, located on the Gulf of Mexico, the Border Wars intensified. The longest battle of the Mexican Revolution was fought at the border town of Naco, Sonora, a 119-day conflict between the forces of Pancho Villa and General Obregón. US Army Buffalo Soldiers stationed at the newly built Fort Naco on the American side came under fire from rebels shooting at them from the Mexican side. The Americans returned fire but didn’t cross into Mexico.

By 1915 the Border Wars took an interesting twist. Venustiano Carranza had assumed control over the Mexican government in the spring and some of his followers drafted what was called the Plan of San Diego which called for a race war inside the United States and a return of the American Southwest to Mexico. The followers of the plan launched raids into Texas, killing civilians and disrupting transportation and telecommunications, which garnered a response from the Texas Rangers and Anglo-American vigilante groups. In a promise of recognition by the United States of his new government, Carranza agreed to hunt down and bring to justice the Mexican rebels who followed the tenets of the plan. President Wilson recognized Carranza as the lawful president of Mexico and the raids ceased. There was a great deal of mistrust of Mexicans and Mexican-Americans among Anglo-American communities in south Texas as a result of the Plan of San Diego and some historians estimate that hundreds of Mexicans and people of Mexican descent were lynched as a result of the raids.

By 1915 the Border Wars took an interesting twist. Venustiano Carranza had assumed control over the Mexican government in the spring and some of his followers drafted what was called the Plan of San Diego which called for a race war inside the United States and a return of the American Southwest to Mexico. The followers of the plan launched raids into Texas, killing civilians and disrupting transportation and telecommunications, which garnered a response from the Texas Rangers and Anglo-American vigilante groups. In a promise of recognition by the United States of his new government, Carranza agreed to hunt down and bring to justice the Mexican rebels who followed the tenets of the plan. President Wilson recognized Carranza as the lawful president of Mexico and the raids ceased. There was a great deal of mistrust of Mexicans and Mexican-Americans among Anglo-American communities in south Texas as a result of the Plan of San Diego and some historians estimate that hundreds of Mexicans and people of Mexican descent were lynched as a result of the raids.

By 1916 the Border Wars intensified even further. In January of that year, a group of supporters of Pancho Villa stopped a train near the town of Santa Isabel, Chihuahua and shot 18 American passengers. Villa’s forces were in desperation mode as they raided towns and trains for supplies and valuables. In November of the previous year Villa had pillaged Hermosillo, Sonora, and in March of 1916 he decided to cross the border and do the same to the town of Columbus, New Mexico. Villa’s 500-man force was defeated by 300 Americans stationed at the fort outside of town. Over a dozen American troops and civilians were killed in the Columbus raid along with sixty to eighty of Pancho Villa’s riders. Villa’s forces would conduct two more cross-border raids in 1916: one in Glenn Springs, Texas and one in Boquillas, Texas. Three US troops were killed in these Texas raids along with one civilian, a young American boy who was caught in the crossfire. The Mexicans took two hostages and retreated across the border after stealing much-needed supplies. In response to Pancho Villa’s attacks, President Woodrow Wilson ordered General John J. Pershing to lead an expedition of 5,000 men into Mexican territory to capture Pancho Villa. The US president also ordered 117,000 members of the National Guard to reinforce the newly built army garrisons along the border. The US expeditionary force went as far south as Pancho Villa’s hometown of Parral, Chihuahua where they met with resistance from those loyal to the Carranza government. The most famous battle of the Border Wars occurred in June of 1916 when the Buffalo Soldiers of the 10th Cavalry were defeated at the Battle of Carrizal. As an interesting footnote to the hostilities in 1916: future general George S. Patton of the 8th Cavalry conducted the United States’ first military engagement using armored vehicles outside the town of San Miguelito in northern Sonora.

By 1917 Woodrow Wilson had ordered the Pancho Villa Expeditionary Force out of Mexico, citing the casualties suffered at the Battle of Carrizal. Wilson’s strategy was to beef up the border with the returning troops to ensure against further cross-border raids. The strife between Mexico and the US took a big international turn in early 1917 when the Zimmerman Telegram was intercepted by British Intelligence and decoded. In the communication the German government officially asked Mexico to join World War I on the side of the Central Powers and requested that Mexico attack the Southwestern United States. In return, Germany would guarantee a return of the American Southwest to Mexico after the war. As the US had not yet entered the war, when the telegram became public it infuriated the Americans and pushed the US closer to war with Germany. The telegram was not the only instance of German meddling in the already tense relationship between the US and Mexico. In 1918 Army Intelligence stationed at Fort Huachuca, Arizona discovered a German military presence in northern Sonora. To the Americans’ surprise, the Germans were scoping out routes for a possible land invasion of the southwestern US through Mexico.

By 1917 Woodrow Wilson had ordered the Pancho Villa Expeditionary Force out of Mexico, citing the casualties suffered at the Battle of Carrizal. Wilson’s strategy was to beef up the border with the returning troops to ensure against further cross-border raids. The strife between Mexico and the US took a big international turn in early 1917 when the Zimmerman Telegram was intercepted by British Intelligence and decoded. In the communication the German government officially asked Mexico to join World War I on the side of the Central Powers and requested that Mexico attack the Southwestern United States. In return, Germany would guarantee a return of the American Southwest to Mexico after the war. As the US had not yet entered the war, when the telegram became public it infuriated the Americans and pushed the US closer to war with Germany. The telegram was not the only instance of German meddling in the already tense relationship between the US and Mexico. In 1918 Army Intelligence stationed at Fort Huachuca, Arizona discovered a German military presence in northern Sonora. To the Americans’ surprise, the Germans were scoping out routes for a possible land invasion of the southwestern US through Mexico.

1918 saw two interesting developments in the Border Wars. A group of Yaqui Indians who were sympathetic to the Mexican Revolution gathered arms and established a small base in a place called Bear Valley, located in southeastern Arizona. They intended to set up a supply line to rebel forces in the northern part of the Mexican state of Sonora. The 10th Cavalry found out about the Yaqui encampment and attacked it. The Yaquis surrendered. The other major development in the Border Wars in 1918 involved Imperial Germany, once again. In August, US Army Lieutenant Colonel Frederick J. Hermann received intelligence from an anonymous Mexican rebel fighter that Mexican federal troops and German advisers were planning an attack on Nogales, Arizona. A pursuit of someone smuggling guns into Mexico from the Arizona side of the border escalated into what was later called the Battle of Ambos Nogales. When the dust settled, dozens of Mexicans, 2 Germans and seven Americans died in this battle which was considered the last major engagement of the Border Wars. The very last skirmish, however happened in June of the next year – 1919 – when American troops joined the Mexican army to hunt down the last remaining loyalists of Pancho Villa. That skirmish was called the Last Battle of Ciudad Juárez and was one for the history books as the last American military engagement on Mexican soil.

1918 saw two interesting developments in the Border Wars. A group of Yaqui Indians who were sympathetic to the Mexican Revolution gathered arms and established a small base in a place called Bear Valley, located in southeastern Arizona. They intended to set up a supply line to rebel forces in the northern part of the Mexican state of Sonora. The 10th Cavalry found out about the Yaqui encampment and attacked it. The Yaquis surrendered. The other major development in the Border Wars in 1918 involved Imperial Germany, once again. In August, US Army Lieutenant Colonel Frederick J. Hermann received intelligence from an anonymous Mexican rebel fighter that Mexican federal troops and German advisers were planning an attack on Nogales, Arizona. A pursuit of someone smuggling guns into Mexico from the Arizona side of the border escalated into what was later called the Battle of Ambos Nogales. When the dust settled, dozens of Mexicans, 2 Germans and seven Americans died in this battle which was considered the last major engagement of the Border Wars. The very last skirmish, however happened in June of the next year – 1919 – when American troops joined the Mexican army to hunt down the last remaining loyalists of Pancho Villa. That skirmish was called the Last Battle of Ciudad Juárez and was one for the history books as the last American military engagement on Mexican soil.

REFERENCES: Various online sources