Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

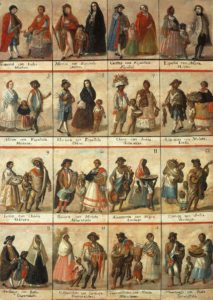

In colonial Mexico in the late 1600s, if a Spanish person had a child with an indigenous woman, the child would be considered mestizo. If that same Spanish man married a woman of African descent, their child would be called mulato. If the mestizo married an indigenous person, their ¾ indigenous child would be considered a coyote. However, if that same mestizo married a Europe an, their child of ¼ indigenous blood would be called a castizo. If that castizo then married a Spaniard, their child, with only 1/8 indigenous background, would be classified as Spanish. But, if that castizo married a half Spanish/Half native mestizo, their children would be called chamizos. That mulato mentioned earlier, well, if he decided to marry an indigenous woman, their offspring would be called a chino cambujo. That’s not to be confused with a lobo who has 3 indigenous grandparents and that one grandparent of African descent. And there were two types of Spaniards: Peninsulares who were born in Spain and Criollos who were born in the New World, which was an important distinction. Did you get all that? There will be a test at the end of this episode.

an, their child of ¼ indigenous blood would be called a castizo. If that castizo then married a Spaniard, their child, with only 1/8 indigenous background, would be classified as Spanish. But, if that castizo married a half Spanish/Half native mestizo, their children would be called chamizos. That mulato mentioned earlier, well, if he decided to marry an indigenous woman, their offspring would be called a chino cambujo. That’s not to be confused with a lobo who has 3 indigenous grandparents and that one grandparent of African descent. And there were two types of Spaniards: Peninsulares who were born in Spain and Criollos who were born in the New World, which was an important distinction. Did you get all that? There will be a test at the end of this episode.

The staggering number of racial classifications found in Mexico by the end of the 1600s did not always exist. In its newly conquered lands in the New World the Spanish Crown established two separate legal and social systems for Europeans and the indigenous. The “República de Indios” included all the laws and expectations made of indigenous people, which was incredibly lengthy and detailed. While newly conquered natives of the country that would later be called Mexico were forced to pay tribute to the Crown, they were considered “born innocent” and not subject to the rigors of the Holy Inquisition. This set of laws recognized indigenous titles of nobility and gave special privileges to certain native groups that helped in the conquest of the Aztec Empire. Tlaxcalans, for example, could ride horses and carry firearms, when most natives of colonial Mexico were forbidden to do so. Although not punishable in a legal sense, indigenous people were also prohibited from wearing certain articles of European clothing. The Spanish of New Spain and their descendants were subject to the laws under the counterpart of the República de Indios called the “República de Españoles.” Spaniards and their descendants had their separate laws and social rules. While the españoles were not required to pay tribute to the Crown, they were subject to the Inquisition. The two separate legal systems worked for a while, and with generations of intermarriage between Europeans, African descendants and the people of the various indigenous groups of Mexico, the racial classifications became more and more difficult to delineate. All non-indigenous regardless of race mixture became subject to the República de Españoles legal authority and were prohibited from living in towns designated as purely indigenous. These two different legal spheres existed until the Bourbon Reforms of the mid-1700s.

The term mestizo, which now means the current blend of races and cultures that formed the modern nation Mexico, had a ring of illegitimacy to it in the early days of Spanish colonial rule. Mestizo originally meant the offspring of one Spanish parent and one indigenous parent, and sometimes these unions were consecrated outside the authority of the Church. A separate racial or socio-economic class called “mestizo” only became recognized about 150 years or some 6 generations after the Conquest. By then – the late 1600s – there were numerous combinations of races and ethnicities, some of which were mentioned earlier. The term casta was often used to describe people belonging to the various mixtures of the races. The word, which sounds like the English, “caste,” originally meant “lineage” or “descent” in Spanish, Portuguese and other Iberian languages. Later the term “casta” would describe the system of classification for the untold number of Mexican racial blends.

belonging to the various mixtures of the races. The word, which sounds like the English, “caste,” originally meant “lineage” or “descent” in Spanish, Portuguese and other Iberian languages. Later the term “casta” would describe the system of classification for the untold number of Mexican racial blends.

Scholars debate where the multitude of terms came from. There were no laws passed or royal decrees issued to assign terms to and grant privileges to the people who belonged to the various labels. The different classifications – from mulato to morisca to torne atrás – may not have been given to these groups by the ruling elite. Some may look at the names from a 21st Century perspective and believe the labels to be demeaning and pejorative. For example, a person who was three quarters black and one quarter indigenous was called a lobo, or “wolf,” in English. If a mestizo man married an indigenous woman, their child would be a “coyote,” referencing the animal of the same name. If a castizo – a man with a Spanish father and mestiza mother – married a mestiza, their child, who would be 5/8 Spanish and 3/8 native would be called chamizo, which loosely translates to English as “burned piece of wood.” Those eager to cry “racism!” today might think it is obvious that such terms as “coyote” and “burned piece of wood” came from the whiter European elites and was used in a derogatory way, because who would ever want to call themselves such things? Perhaps this is not all as serious as some scholars and racial revisionists of today would have us think. Perhaps these terms bubbled up from the folk and were used proudly or jokingly to self-identify. We see similar things in the modern day. Can we draw conclusions from those examples? I will step out of the role of objective podcaster to give an example from my personal life. My own mother, who is a mix  of German, Delaware Indian, Scottish, French, English and Swedish often gets many questions from strangers about her ethnicity, which is a mystery to those who think it is important. I have been in her presence when people have used Spanish with her, have asked her about her racial background or even wondered what tribe she was from. Ever since I was a little kid my mom would always respond with this, “I’m a mutt.” So, she is self-describing as a mongrel dog. In a phone conversation with her on April 10, 2021, I asked my mom why she calls herself a mongrel dog when asked about her heritage. She said, “Oh, I don’t know,” and just chuckled. No formal power structure put that term in her head. There are others in America who are of mixed heritage or don’t know anything about their own ethnic background or who just don’t care, who say they are “Heinz 57.” So, are these people demeaning themselves and invoking patriarchal, colonialist, racially suppressive terms by identifying as bottles of ketchup? Are these terms “racism” at all or is it part of a lightly humorous take on something that might not be all that important to the person self-identifying with their respective label?

of German, Delaware Indian, Scottish, French, English and Swedish often gets many questions from strangers about her ethnicity, which is a mystery to those who think it is important. I have been in her presence when people have used Spanish with her, have asked her about her racial background or even wondered what tribe she was from. Ever since I was a little kid my mom would always respond with this, “I’m a mutt.” So, she is self-describing as a mongrel dog. In a phone conversation with her on April 10, 2021, I asked my mom why she calls herself a mongrel dog when asked about her heritage. She said, “Oh, I don’t know,” and just chuckled. No formal power structure put that term in her head. There are others in America who are of mixed heritage or don’t know anything about their own ethnic background or who just don’t care, who say they are “Heinz 57.” So, are these people demeaning themselves and invoking patriarchal, colonialist, racially suppressive terms by identifying as bottles of ketchup? Are these terms “racism” at all or is it part of a lightly humorous take on something that might not be all that important to the person self-identifying with their respective label?

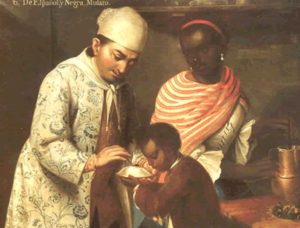

Back to New Spain, In the eyes of the colonials, Europeans were at the top of the socio-economic order, if in name only. The Spaniard who mixed with indigenous could have the indigenous “washed out” of his family in 3 generations if the descendants stuck to marrying European. Hence, we see in the paintings, the offspring of a Spaniard marrying a castiza called “español.” This was not the case with “Africanness” and no matter how many generations married into other races, the black was always there. 8 generations into their colonial project in the New World, the Spaniards had a hard time classifying the mixes they saw around them. Perhaps this is why some of these terms are so borderline humorous that they were most likely not taken seriously. Take for example, the mix of a European father and a mother whose parents were Spanish and albino of any race. That person was classified as “tente en el aire.” The closest English translation that makes sense of this old Iberian term is “hands in the air,” as in “who the heck knows?” If the tente en el aire married a mulata, the literal racial classification for their offspring was “no te entiendo,” or in English, “I don’t understand you.” Such classifications showed the futility of trying to make this system work. It got to the point where people were just unclassifiable, and some people were clearly having fun with this. By the time of Mexican Independence, some 12 generations after the Conquest, the only term from this system to survive was mestizo, and as mentioned before, that took on a new meaning to describe the blend of everyone in Mexico into a new ethnicity and culture.

We see the multitude of racial and ethnic terms of colonial Mexico in two distinct places: The first was in legal documents or other written accounts from the time. The second was in art, specifically in what is known today as the “Casta paintings.” The legal documents, like police reports of today, see the need to mention race as a descriptor but there never seems to have been anything important connected with these racial classifications. For example, nothing exists in the volumes of colonial legal proceedings that penalizes or sanctions anyone for doing something outside the bounds of their racial or ethnic designation. This was because there were no actual laws penalizing the crossing of these somewhat arbitrary boundaries going beyond the special treatment afforded to the indigenous in the early colonial period. The documents only mention in passing whether the person was albarazado, mestizo, china cambuja, or whatever. There was little written about all of this outside the legal realm which give scholars little to go on to determine just how important this classification system really was.

We see the multitude of racial and ethnic terms of colonial Mexico in two distinct places: The first was in legal documents or other written accounts from the time. The second was in art, specifically in what is known today as the “Casta paintings.” The legal documents, like police reports of today, see the need to mention race as a descriptor but there never seems to have been anything important connected with these racial classifications. For example, nothing exists in the volumes of colonial legal proceedings that penalizes or sanctions anyone for doing something outside the bounds of their racial or ethnic designation. This was because there were no actual laws penalizing the crossing of these somewhat arbitrary boundaries going beyond the special treatment afforded to the indigenous in the early colonial period. The documents only mention in passing whether the person was albarazado, mestizo, china cambuja, or whatever. There was little written about all of this outside the legal realm which give scholars little to go on to determine just how important this classification system really was.

The colonial era left modern people a treasure trove of illustrations of these racial designations in the form of the famous Casta paintings. These paintings began being made in Mexico in the late 1600s and early 1700s by Mexican artists. They showed scenes of family life, almost always a man and a woman, each of a different race, together with their offspring, and labels on the top or bottom of the canvas to denote the name of the racial blend. Most all art in the New World up to this time had been religious, and the style of these paintings, including postures and facial expressions, are reminiscent of Renaissance depictions of the Holy Family, saints or angels. The Casta paintings were done in sets, always with the españoles as the first in the series, followed by the mestizo. Later interpretations of these paintings see a rigidity in the racial classifications which cause some scholars to assume rigidity in real-life socio-economic hierarchy. That may be easy to assume and is perhaps a little lazy in an academic sense given the reality of Mexico in the 17th and 18th Centuries. A person experiencing poverty in Spain who arrived in colonial Mexico did not automatically receive magical privileges when he stepped off the boat in the New World. He most likely labored in a mine or worked a menial agricultural job and remained poor throughout his life. While he was legally allowed to carry a sword due to his race, he probably could not have afforded one. And while the indios were low on the racial totem pole, along with the people of African heritage, this newly-arrived poor person from Spain most likely marveled at the riches of the indigenous elite classes or felt a sense of envy upon seeing the prosperity of a successful African or mulato merchant. These categories as seen in the casta paintings apparently were very fluid and as discussed earlier, sometimes people were just not classifiable. By the time the paintings debuted plenty of racial blending had occurred.

By the mid-1700s the casta paintings became incredibly popular in Europe. Europeans were intensely curious about the New World, about the exotic flora, fauna and people in the newly discovered lands beyond the seas. Europe was coming into the Enlightenment and with it came a need to classify and catalog everything found in the world, including people. The casta paintings were collected by European elites and exhibited in what were called “cabinets of curiosity” in Spain, which were rooms in private upper-class residences featuring artifacts and other items of interest from the world beyond Europe. Pertinent to this discussion, to the European of the mid-18th Century, part of the fascination with Mexico was the very fact that the races blended there. To some the mixing of the races indicated a degenerate and haphazard society. Many could not imagine people of different ethnic and racial backgrounds living together as they did in New Spain because that was so outside the continental European experience. The casta paintings changed many minds of the Europeans who saw them. Instead of the chaos imagined, the beautifully executed paintings showed an abundant, civilized and organized life in colonial Mexico. The tender family scenes showed to the world that this complex and prosperous multi-racial society was all bound together by love.

REFERENCES

Katzew, Ilona. Casta Painting: Images of Race in Eighteenth-Century Mexico. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2005. We are Amazon affiliates. Buy the book on Amazon here: https://amzn.to/3t8nDsw

Martinez,Maria Elena. Genealogical Fictions: Limpieza de Sangre, Religion, and Gender in Colonial Mexico, Stanford: Stanford University Press 2008, p. 265.