Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

When the Spanish conquistadors arrived at the Mexican capital of Tenochtitlán in 1519 they were not met with hostility. The emperor knew Cortés was coming, and curious about the Spaniard’s intentions, he welcomed the visitor and his men as honored guests. Because of this cordial reception many first-hand European accounts exist of a living and breathing Aztec Empire. All of Cortés’ contingent was amazed at the city. The massive imperial palace complex drew much attention. There were swimming pools, lavish apartments for the emperor’s family and foreign dignitaries, lush gardens where thousands of flowers bloomed and the often-wrote-about legendary private zoo of Montezuma, explored in depth in Mexico Unexplained Episode number 43. https://mexicounexplained.com/montezumas-zoo/ Besides animals from throughout the vast Aztec realm, Montezuma’s Zoo had a section not seen in any modern zoo: an area for human curiosities. Dwarves and people with various deformities and disabilities who hailed from all parts of the empire were housed in the zoo, occupying a special place. As these people were separated from their families, the State compensated family members generously, taking care of them for life. It was seen as a blessing to have a relative chosen to live in the imperial palace’s human zoo. Dwarves and hunchbacks of diverse ethnicities – Mexica, Totonac, Zapotec, and so on – served as court jesters, musical performers and held other special roles at court. Nobility and other notables from client states within the Aztec Empire were especially attracted to the imperial human zoo, but unlike gawkers at carnival sideshows in America’s not-so-distant past, the curious visitors looked upon the human zoo’s inhabitants with subtle reverence. The Spanish found the roles of hunchbacks and dwarfs at the Aztec court familiar, as European monarchs had used these unique people for similar things, for entertainment and to play the fool or serve in a role of harlequin or clown.

When the Spanish conquistadors arrived at the Mexican capital of Tenochtitlán in 1519 they were not met with hostility. The emperor knew Cortés was coming, and curious about the Spaniard’s intentions, he welcomed the visitor and his men as honored guests. Because of this cordial reception many first-hand European accounts exist of a living and breathing Aztec Empire. All of Cortés’ contingent was amazed at the city. The massive imperial palace complex drew much attention. There were swimming pools, lavish apartments for the emperor’s family and foreign dignitaries, lush gardens where thousands of flowers bloomed and the often-wrote-about legendary private zoo of Montezuma, explored in depth in Mexico Unexplained Episode number 43. https://mexicounexplained.com/montezumas-zoo/ Besides animals from throughout the vast Aztec realm, Montezuma’s Zoo had a section not seen in any modern zoo: an area for human curiosities. Dwarves and people with various deformities and disabilities who hailed from all parts of the empire were housed in the zoo, occupying a special place. As these people were separated from their families, the State compensated family members generously, taking care of them for life. It was seen as a blessing to have a relative chosen to live in the imperial palace’s human zoo. Dwarves and hunchbacks of diverse ethnicities – Mexica, Totonac, Zapotec, and so on – served as court jesters, musical performers and held other special roles at court. Nobility and other notables from client states within the Aztec Empire were especially attracted to the imperial human zoo, but unlike gawkers at carnival sideshows in America’s not-so-distant past, the curious visitors looked upon the human zoo’s inhabitants with subtle reverence. The Spanish found the roles of hunchbacks and dwarfs at the Aztec court familiar, as European monarchs had used these unique people for similar things, for entertainment and to play the fool or serve in a role of harlequin or clown.

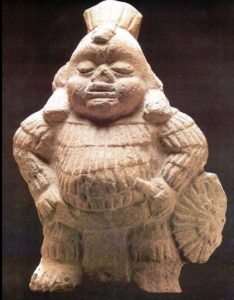

The special role of dwarfs and hunchbacks in ancient Mexican society predates the Aztecs by perhaps thousands of years and most of what we know about this subject can be found in art and inscriptions left behind by various civilizations. Some cultures, such as the Maya in particular, often depicted captives or enemy sacrificial victims as being smaller in scale in their art, and this is not to be confused with depictions of dwarfs. This also goes for the various artistic representations of children across civilizations. Archaeologists differentiate depictions of children and smaller adults in Mesoamerican art from those of dwarfs by looking at certain characteristics. The most common form of biological dwarfism, called achondroplasia, has the following physical attributes: abnormally short and fleshy limbs, a disproportionately large head with a prominent forehead, a protruding abdomen, a sunken face, and a somewhat drooping lower lip.

The Olmecs, whose culture flourished in the Gulf coastal region of Mexico from about 1200 BC to 400 AD, left behind many examples of dwarfs in the form of figurines. Many sculptures previously identified as babies are in fact depictions of dwarfs. In Olmec art we see also, but to a lesser degree, depictions of hunchbacks. As the Olmecs left behind no written language, it is impossible to tell what roles these types of people played in Olmec society.

The dwarf/hunchback motif seems a bit overabundant in classic ancient Maya art. Researchers are still trying to figure out why that is. It is probably not because dwarfism or other physical deformities were more prevalent in ancient Maya civilization, as not a single skeleton of a dwarf or hunchback has ever been found in a Maya excavation. Whatever their true numbers were in the ancient Maya world, the art and artifacts left behind indicate the special role of dwarfs and to a lesser degree, hunchbacks, in Maya society. The biggest cache of hunchback and dwarf figurines has been found on the island of Jaina in the Gulf of Mexico off the coast of the modern Mexican state of Campeche. Jaina is separated from the mainland by a small tidal inlet and in the local Maya dialect the name of the place means “Temple in the Water.” In the Classic Maya period the island served as an elite burial ground with some 20,000 graves now identified. Archaeologists have discovered hundreds of thousands of artifacts in the 1,000 or so graves excavated there and in the ruins of the town on that island. Among these artifacts are between 50 and 100 figurines or figurine fragments depicting dwarfs and hunchbacks. The earlier ceramic phase called Jaina One dates from 600 to 800 AD and is characterized by hand-formed figurines. It was during this phase when hunchbacks were more prevalent. During the next phase, called Jaina Two, dating from 800 to 1000 AD dwarfs were more common and they were made in molds instead of being completely hand-fashioned. Both hunchback and dwarf figurines at Jaina are often depicted wearing headdresses featuring animal heads skewed to one side. This lack of symmetry is unusual in Maya art. Some researchers theorize that the crooked headdresses form some sort of contrast to the straightened and proudly worn animal headdresses of the Maya nobility so often depicted in art. Again, archaeologists and art historians are at a loss to explain the reasons for all this. One thing is clear, though, dwarfs and hunchbacks must have had or represented special status in order to be found in so many elite graves at such an important regional Maya burial site. Some researchers theorize that there must have been a widespread belief among the ancient Maya that dwarfs and hunchbacks would make useful companions in the journey to the afterlife. There are other examples of this belief in at least one other part of ancient Mexico, Tlaxcala. As noted by native scribes at the time of the Conquest, when a high-ranking Tlaxcalan ruler died, his wives, his slaves and his hunchbacks and dwarfs were buried alive with him, to ensure a peaceful and smooth transition to the underworld. If we can extrapolate a little here, perhaps because of the sheer rarity of the existence of hunchbacks and dwarfs in real life, perhaps clay figurines were created because there were not enough real ones to fulfill these much-needed burial roles.

The dwarf/hunchback motif seems a bit overabundant in classic ancient Maya art. Researchers are still trying to figure out why that is. It is probably not because dwarfism or other physical deformities were more prevalent in ancient Maya civilization, as not a single skeleton of a dwarf or hunchback has ever been found in a Maya excavation. Whatever their true numbers were in the ancient Maya world, the art and artifacts left behind indicate the special role of dwarfs and to a lesser degree, hunchbacks, in Maya society. The biggest cache of hunchback and dwarf figurines has been found on the island of Jaina in the Gulf of Mexico off the coast of the modern Mexican state of Campeche. Jaina is separated from the mainland by a small tidal inlet and in the local Maya dialect the name of the place means “Temple in the Water.” In the Classic Maya period the island served as an elite burial ground with some 20,000 graves now identified. Archaeologists have discovered hundreds of thousands of artifacts in the 1,000 or so graves excavated there and in the ruins of the town on that island. Among these artifacts are between 50 and 100 figurines or figurine fragments depicting dwarfs and hunchbacks. The earlier ceramic phase called Jaina One dates from 600 to 800 AD and is characterized by hand-formed figurines. It was during this phase when hunchbacks were more prevalent. During the next phase, called Jaina Two, dating from 800 to 1000 AD dwarfs were more common and they were made in molds instead of being completely hand-fashioned. Both hunchback and dwarf figurines at Jaina are often depicted wearing headdresses featuring animal heads skewed to one side. This lack of symmetry is unusual in Maya art. Some researchers theorize that the crooked headdresses form some sort of contrast to the straightened and proudly worn animal headdresses of the Maya nobility so often depicted in art. Again, archaeologists and art historians are at a loss to explain the reasons for all this. One thing is clear, though, dwarfs and hunchbacks must have had or represented special status in order to be found in so many elite graves at such an important regional Maya burial site. Some researchers theorize that there must have been a widespread belief among the ancient Maya that dwarfs and hunchbacks would make useful companions in the journey to the afterlife. There are other examples of this belief in at least one other part of ancient Mexico, Tlaxcala. As noted by native scribes at the time of the Conquest, when a high-ranking Tlaxcalan ruler died, his wives, his slaves and his hunchbacks and dwarfs were buried alive with him, to ensure a peaceful and smooth transition to the underworld. If we can extrapolate a little here, perhaps because of the sheer rarity of the existence of hunchbacks and dwarfs in real life, perhaps clay figurines were created because there were not enough real ones to fulfill these much-needed burial roles.

Some researchers trace the Maya preoccupation with dwarfs and hunchbacks back to an earlier civilization that may have influenced the ancient Maya, the central Mexican powerhouse of Teotihuacán. Teotihuacán was on the decline while Maya civilization was on the rise and the two cultures had direct contact with each other even though they were separated by hundreds of miles of mountains and jungles. In 1930 an archaeologist named Beyer first identified what has since been known as “The Fat God” found in various artistic representations in Teotihuacán and the Gulf Coast. Since then, this god has been found in the northern Yucatán and is represented in the corpus of figurines found at Jaina. Some claim the Fat God is really a dwarf and through trade with the Maya the concept of dwarfs having special status or magical powers was introduced to the Maya world. As an interesting aside, the Classic Maya city of Uxmal has a fascinating creation story involving a dwarf and how he transformed the city into a regional dynamo. To learn more about the magical dwarf and the city of Uxmal please see Mexico Unexplained Episode 185: https://mexicounexplained.com/uxmal-lost-city-of-the-dwarf/

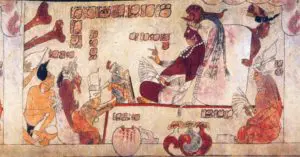

As seen in the later civilization of the Aztecs, the Maya also used dwarfs and hunchbacks at royal courts for entertainment purposes. The proof of this is found throughout Maya art from the Classic period, including murals, monumental architecture, figurines, and scenes on pottery vessels. On a carved Maya column of unknown origin now at the Campeche Museum, one can see a jovial court scene showing a fat dwarf dancing before a king who sits on a throne, amused. On the bottom of the column, two dwarfs play horns to round out the scene. There are many other examples. In Room 3 of Structure 1 at Bonampak, we see a courtly parade of sacrificial victims surrounded by dancers. A dwarf happily beats a drum to the music as he is carried on a litter by several hunchbacks and other deformed figures. In a private collection in Illinois, we find a beautifully painted vase showing a jovial court scene. The vase is probably from the site of Naranjo in northwestern Guatemala near its border with the Mexican state of Tabasco. Here the dwarfs dance, and according to researchers this vase is important because it shows three different types of dwarfs based on different physical characteristics, including a dwarf/hunchback blend. Some researchers theorize that the different dwarfs on the vase may indicate that different types of dwarfs played distinctly different roles within Maya society. Others go for a less complicated explanation and chalk it all up to mere artistic license. Perhaps the artist had never even seen a dwarf before and was using his imagination. Another possible explanation is that the variety of dwarfs or the specific dwarfs on this vase represent a particular myth or story. There is no way to tell.

As seen in the later civilization of the Aztecs, the Maya also used dwarfs and hunchbacks at royal courts for entertainment purposes. The proof of this is found throughout Maya art from the Classic period, including murals, monumental architecture, figurines, and scenes on pottery vessels. On a carved Maya column of unknown origin now at the Campeche Museum, one can see a jovial court scene showing a fat dwarf dancing before a king who sits on a throne, amused. On the bottom of the column, two dwarfs play horns to round out the scene. There are many other examples. In Room 3 of Structure 1 at Bonampak, we see a courtly parade of sacrificial victims surrounded by dancers. A dwarf happily beats a drum to the music as he is carried on a litter by several hunchbacks and other deformed figures. In a private collection in Illinois, we find a beautifully painted vase showing a jovial court scene. The vase is probably from the site of Naranjo in northwestern Guatemala near its border with the Mexican state of Tabasco. Here the dwarfs dance, and according to researchers this vase is important because it shows three different types of dwarfs based on different physical characteristics, including a dwarf/hunchback blend. Some researchers theorize that the different dwarfs on the vase may indicate that different types of dwarfs played distinctly different roles within Maya society. Others go for a less complicated explanation and chalk it all up to mere artistic license. Perhaps the artist had never even seen a dwarf before and was using his imagination. Another possible explanation is that the variety of dwarfs or the specific dwarfs on this vase represent a particular myth or story. There is no way to tell.

Some Maya sites put a greater emphasis on the importance of dwarfs and hunchbacks and at other sites they are seldom seen or nonexistent in art and artifacts. Sometimes this emphasis stretches across large periods of time. Art historian Virginia E. Miller in her 1980 article, “The Dwarf Motif in Classic Maya Art,” makes these comments:

“ The representation of dwarfs at some sites over a long period of time suggests two possibilities: Frist, dwarfism was prevalent either within the general population or in the ruling family, and each dwarf represented is a different individual. Second, only one dwarf was born at the site, but he assumed such importance that subsequent rulers wished to include his portrait on their monuments. Even if only one dwarf was born into the ruling line, such an unusual being could have added special status to the hereditary elite. It is even possible that dwarfs born outside the ruling family were adopted because of presumed magical powers or other qualities that may have been attributed to them. This is not a farfetched possibility, considering that the Mexica (Aztecs) supposedly deliberately deformed children for service in the emperor’s court, a practice also noted in antiquity and at even later periods in Europe.”

Another recent theory postulates that dwarfs served important roles in rituals as stand-ins for children. A fully adult dwarf with the maturity and expertise of any grown person could have performed rituals and ceremonies intended for children with less risk of mistakes. Perhaps the ancient Mexicans saw dwarfs as “superchildren” in this regard.

Another recent theory postulates that dwarfs served important roles in rituals as stand-ins for children. A fully adult dwarf with the maturity and expertise of any grown person could have performed rituals and ceremonies intended for children with less risk of mistakes. Perhaps the ancient Mexicans saw dwarfs as “superchildren” in this regard.

In modern Western society persons with disabilities have traditionally been marginalized and held up as objects of derision and scorn outside their immediate families. The ancient Mexicans of various cultures across the centuries did not feel the same. Although it is not fully understood exactly how hunchbacks and dwarfs fit into the societies of pre-Hispanic Mexico, it is clear that they were seen as special and unique people with important roles to play.

REFERENCES

Corson, Christopher. Maya Anthropomorphic Figures from Jaina Island, Campeche. Ramona, CA: Ballena Press, 1976.

Miller, Virginia E. “The Dwarf Motif in Classic Maya Art. In Fourth Palenque Round Table, 1980,” edited by E. Benson, pp. 141-153. Palenque Round Table Series Volume VI, edited by

M. Robertson. Pre-Columbian Art Research Institute, San Francisco.

Storniolo, Judith A. “Ancient Mythical Dwarfs in Modern Yucatan.” In, Expedition, vol. 51, no. 1, pp. 18-24.