Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

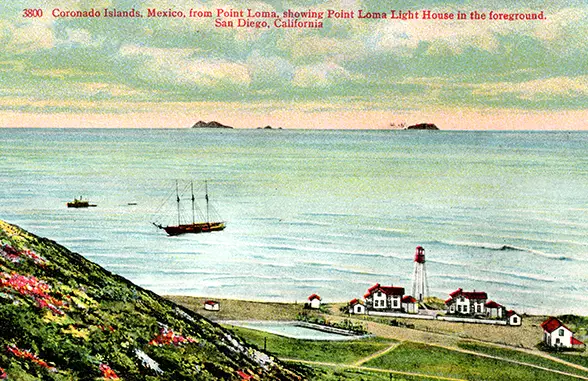

Looking southwest from the beaches of San Diego, California, you can see a small archipelago off the coast which represents the northernmost island territory belonging to Mexico. The Islas Coronado, or Coronado Islands, is a small Mexican island group located in the Pacific Ocean off the coast of Baja California about 20 miles from San Diego. Although small and seemingly insignificant, the Coronados is a place of captivating natural beauty, enigmatic history, and interesting tales that span centuries. The islands have connections to pirates, bootleggers, casino operators, sealers, fisherman, naturalists and Scientology. Not very many Americans know of this mysterious group of islands that are so close to their western shores.

Looking southwest from the beaches of San Diego, California, you can see a small archipelago off the coast which represents the northernmost island territory belonging to Mexico. The Islas Coronado, or Coronado Islands, is a small Mexican island group located in the Pacific Ocean off the coast of Baja California about 20 miles from San Diego. Although small and seemingly insignificant, the Coronados is a place of captivating natural beauty, enigmatic history, and interesting tales that span centuries. The islands have connections to pirates, bootleggers, casino operators, sealers, fisherman, naturalists and Scientology. Not very many Americans know of this mysterious group of islands that are so close to their western shores.

The story of the Islas Coronado begins with their geological origins. These islands – Coronado Norte, Coronado Sur, Coronado Centro, and the smallest, Pilón de Azúcar – are rocky outcrops with a unique geological history. They are the result of volcanic activity that took place millions of years ago. This volcanic origin gives the islands their distinctive rugged terrain and dramatic cliffs that plunge into the Pacific Ocean. The largest island is South Coronado which is two miles long and a half mile wide. The guano-washed Pilón de Azúcar is only 17 acres in area. The geological formation of the islands also contributes to their ecological diversity. The cliffs and caves on the islands provide nesting sites for various bird species, including cormorants, pelicans, and seagulls. The waters surrounding the islands are rich in marine life, with numerous fish species, sea lions, and seals calling the area home. These islands were designated as a protected nature reserve by the Mexican government, a testament to their ecological significance.

Before Europeans arrived, the Islas Coronado were visited by indigenous peoples, primarily the Kumeyaay. As there is no source of fresh water on any of the 4 islands, the Kumeyaay are believed to have visited and used the islands for fishing, trading, and potentially as spiritual or ceremonial sites. The Kumeyaay called the islands Mat hasil ewik kakap. The tribe just north of the Kumeyaay, in what is now modern San Diego County, the Luiseño people, also known as the Payómkawichum, called the Coronados Mexéelam. Archaeologists have discovered the remains of temporary pre-Hispanic native encampments on the north and south islands. Artifacts found at these sites include stone tools, trash middens and fragments of ceramics that appear to be Yuman in origin and may  have been used for cooking or for carrying fresh water to the islands. The first European to sight the Islas Coronado in 1542 was Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo, sailing for Spain. He named them Las Islas Desiertas, or in English, “The Desert Isles” for their stark and unwelcoming landscapes. The islands got their current name in 1602 when Father Antonio de la Ascención, a priest who was sailing with the Sebastián Vizcaino expedition, christened them Los Cuatro Coronados, in honor of the Four Crowned Martyrs who were early Christian saints. While the name “Islas Coronado” has stuck on Spanish and Mexican maps, the islands have had other names and nicknames over the years including, Sarcophagi Islands, Dead Man’s Island, Old Stone Face, the Pirate Islands, Corpus Christi and the Sentinels of San Diego Bay.

have been used for cooking or for carrying fresh water to the islands. The first European to sight the Islas Coronado in 1542 was Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo, sailing for Spain. He named them Las Islas Desiertas, or in English, “The Desert Isles” for their stark and unwelcoming landscapes. The islands got their current name in 1602 when Father Antonio de la Ascención, a priest who was sailing with the Sebastián Vizcaino expedition, christened them Los Cuatro Coronados, in honor of the Four Crowned Martyrs who were early Christian saints. While the name “Islas Coronado” has stuck on Spanish and Mexican maps, the islands have had other names and nicknames over the years including, Sarcophagi Islands, Dead Man’s Island, Old Stone Face, the Pirate Islands, Corpus Christi and the Sentinels of San Diego Bay.

One of the most intriguing aspects of the Islas Coronado’s history is their association with pirates. During the Golden Age of Piracy in the late 17th and early 18th centuries, these islands served as convenient hideouts and strategic locations for high seas adventurers of many nationalities. Legends tell of buried treasure hidden in caves, secret pirate rendezvous, and daring escapes from pursuing authorities. One of the most famous pirates rumored to have visited the Coronados was the notorious English pirate Thomas Cavendish, who wreaked havoc along the coasts of Mexico in the late 16th century. In one story, Cavendish preyed upon a galleon carrying 122,000 pesos in gold and 2,000,000 pesos in silver and found a secret hiding place for part of his newly acquired treasure somewhere in the Coronado Islands. Another famous pirate who stopped at this tiny archipelago was Hipólito Bouchard, a buccaneer from the newly independent country of Argentina, who sacked San Juan Capistrano in Spanish California in 1818 and supposedly stashed the loot from his plunder somewhere on Coronado Sur. Locals on the mainland tell stories of a Spanish pirate of the early 1800s named José Arvaez who used the southern island as a base, preying on ships from the island’s only bay now called Smuggler’s Cove or Pirate’s Cove. Arvaez allegedly took over a British ship called the Chelsea, but scholars have been unable to verify the existence of the ship or the existence of the pirate Arvaez. Although these stories are largely based on legend and anecdotal accounts, the mystique of buried treasure and swashbuckling adventurers continues to capture the imagination of treasure hunters and history enthusiasts alike.

The new nation of Mexico did nothing with the islands when they became part of the country’s territory at independence in 1821. During the first half of the 19th century, the Coronados were visited by Russian seal hunters, Japanese abalone fisherman and curious Yankees. When the Mexican War broke out, US forces occupied the islands during the naval blockade of San Diego, and the islands became a base of operations for both naval and land activities. At the war’s end with the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo in place, the Islas Coronado barely made it as part of Mexican territory and were thus now the northernmost islands of Mexico. In 1872 a quarry opened on the north island and lasted about 10 years. Starting in the 1870s the Mexican navy began patrolling the islands to shoo away trespassers and those who would engage in illegal activities. As regimes changed in Mexico City, so did priorities, and by the beginning of the 20th Century the neglected islands became a center for human smuggling, specifically for serving as a way station for Chinese immigrants entering the US. In 1911 10 Chinese nationals were stranded in the Coronados by San Diego smugglers who never returned to pick them up. Some fishermen spotted them and reported that they were emaciated and delirious. They were eventually picked up and returned to Ensenada.

The new nation of Mexico did nothing with the islands when they became part of the country’s territory at independence in 1821. During the first half of the 19th century, the Coronados were visited by Russian seal hunters, Japanese abalone fisherman and curious Yankees. When the Mexican War broke out, US forces occupied the islands during the naval blockade of San Diego, and the islands became a base of operations for both naval and land activities. At the war’s end with the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo in place, the Islas Coronado barely made it as part of Mexican territory and were thus now the northernmost islands of Mexico. In 1872 a quarry opened on the north island and lasted about 10 years. Starting in the 1870s the Mexican navy began patrolling the islands to shoo away trespassers and those who would engage in illegal activities. As regimes changed in Mexico City, so did priorities, and by the beginning of the 20th Century the neglected islands became a center for human smuggling, specifically for serving as a way station for Chinese immigrants entering the US. In 1911 10 Chinese nationals were stranded in the Coronados by San Diego smugglers who never returned to pick them up. Some fishermen spotted them and reported that they were emaciated and delirious. They were eventually picked up and returned to Ensenada.

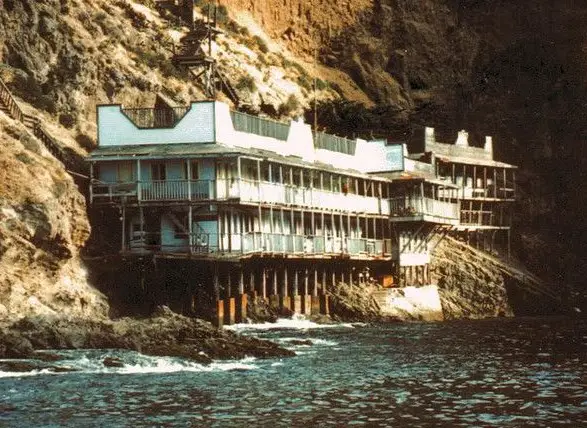

The 1920s and 1930s were a special era for the Islas Coronado. With Prohibition in full swing in the US, bars and casinos in Ensenada, Rosarito Beach and Tijuana were doing an incredible amount of business. In the early 1930s, the man who built Tijuana’s jai alai stadium, Mariano Escobedo, teamed up with San Diego lumber magnate Fred Hamilton, to build a high-end development on the rocky cliffs of Pirate’s Cove on South Island. At a cost of over $200,000, the Coronado Islands Yacht Club opened in 1933. This was an elaborate 2-story building that housed a 60-room hotel, a casino, a cabaret and a bar, and was flanked by private bungalows. A few months after its opening, the American government repealed prohibition and the next year the Mexican government banned casino gambling. In December of 1934 the Coronado Islands Yacht Club closed its doors for good. In ensuing years, the building would house the dozen or so members of the Mexican military stationed on the island. In the 1970s the building fell into serious disrepair. A violent storm in 1988 finished off the building, completely wrecking it, leaving only its stone foundation.

The 1940s saw the islands’ curious connection to Scientology. In May of 1943 in the middle of World War Two, the U. S. Navy’s USS PC-815 conducted unauthorized gunnery exercises and shelled the Coronado Islands with live ammunition. The American Lieutenant Commander in charge of these exercises was L. Ron Hubbard who would later become the founding father of Scientology. Lieutenant Commander Hubbard claimed he thought the Islas Coronado were uninhabited and belonged to the United States. The islands were occupied by the Mexican Coast Guard at the time and the Mexican government filed a formal grievance with the United States because of what happened. To prevent an international incident, Hubbard was relieved of command.

The 1940s saw the islands’ curious connection to Scientology. In May of 1943 in the middle of World War Two, the U. S. Navy’s USS PC-815 conducted unauthorized gunnery exercises and shelled the Coronado Islands with live ammunition. The American Lieutenant Commander in charge of these exercises was L. Ron Hubbard who would later become the founding father of Scientology. Lieutenant Commander Hubbard claimed he thought the Islas Coronado were uninhabited and belonged to the United States. The islands were occupied by the Mexican Coast Guard at the time and the Mexican government filed a formal grievance with the United States because of what happened. To prevent an international incident, Hubbard was relieved of command.

During the mid-20th Century, the Coronados saw many visitors and even a few people tried living there long-term. An eccentric American woman called “Crawfish Jake” ran a small eating establishment at Smugglers Cove, near the site of the old casino. She would catch, cook and serve seafood to boaters who went ashore. She accepted payment in the form of fresh water and other supplies. A Mexican hermit named Manuel Aguilar lived alone on North Coronado, catching lobsters for resale to restaurants in Tijuana and Ensenada. A regular boat from Ensenada would come to pick up the lobsters and bring Aguilar water and other necessities. Once the boat hadn’t shown up for two weeks, so Aguilar rowed his small boat all the way to San Diego some 20 miles away. He never returned to Coronado Norte.

Amid the beauty and rugged charm of the Islas Coronado, there exist eerie and enigmatic legends associated with the archipelago. Even back to the 1860s, the San Diego Union newspaper told tales of otherworldly mirages and glowing lights appearing over the fog-shrouded islands. Visitors to Coronado Norte, especially, have reported strange phenomena over the years, including mysterious lights, unusual sounds, and glowing apparitions. Some believe that the spirits of past inhabitants and visitors who met untimely ends on the island continue to haunt its shores. The haunting tales of Isla Norte serve as a stark contrast to its breathtaking natural beauty. Another legend tied to the southern island has to do with repeated sightings of a ghost of a Native American woman who weeps incessantly and seems to be lost and crying for help. Some believe that her essence is caught in some sort of time vortex, and she doesn’t know how to get back to her own time.

In contemporary times, the Islas Coronado continue to captivate adventurers, researchers, and nature enthusiasts. Despite their remote location and relative obscurity, the islands have become popular destinations for divers, birdwatchers, and nature lovers. As a wildlife refuge protected by the Mexican government, no humans are allowed onshore except for Mexican military personnel and scientists with proper permits. The unique flora and fauna of the islands, including the rare Coronado ironwood tree – Lyonothamnus floribundus – are significant attractions for researchers and others who appreciate the biodiversity and ecological importance of the small archipelago. The Mexican government is currently exploring ways to use the islands as an ecotourism destination and may develop a visitor’s center at Pirate’s Cove near the old casino at some point in the near future.

In contemporary times, the Islas Coronado continue to captivate adventurers, researchers, and nature enthusiasts. Despite their remote location and relative obscurity, the islands have become popular destinations for divers, birdwatchers, and nature lovers. As a wildlife refuge protected by the Mexican government, no humans are allowed onshore except for Mexican military personnel and scientists with proper permits. The unique flora and fauna of the islands, including the rare Coronado ironwood tree – Lyonothamnus floribundus – are significant attractions for researchers and others who appreciate the biodiversity and ecological importance of the small archipelago. The Mexican government is currently exploring ways to use the islands as an ecotourism destination and may develop a visitor’s center at Pirate’s Cove near the old casino at some point in the near future.

The Islas Coronado are not only natural treasures but also historical and cultural gems. They invite exploration, research, and the uncovering of the many secrets they hold. As ongoing discoveries are made, the islands reveal their hidden stories and continue to intrigue and inspire.