Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

The place is Tijuana, near Mexico’s border with the United States. The time is the present day. In the morning hours Virginia begins setting up her stand in front of Panteón Numero Uno. Also known as the old Puerta Blanca Cemetery because of the white arch at its entrance, the panteón is located on Avenida Venustiano Carranza in a residential neighborhood and receives hundreds of visitors per day. Besides the occasional breaks for family functions and holidays, for over 40 years Virginia has been a loyal sentinel manning her post: a small curio stand right outside the white arch of the graveyard. Besides the usual rosaries and standard religious icons, Virginia specializes in items featuring the image of a young man in a green shirt and green hat. Some of her most popular items are plaster-cast busts of this person, some of them painted with overarching eyebrows and pink lips, appearing almost comical. A keychain with this young man’s face will set a person back 18 pesos, about as much as a small bag of street churros available at a neighboring food vendor. The image found on many items in Virginia’s stand is that of Juan Soldado, who in life was known as Juan Castillo Morales. Virginia and other devotees often refer to him affectionately as “Juanito,” “Little Juan,” or “El Soldadito,” “the little soldier.” Panteón Numero Uno contains both the place of death and the grave of Juan Soldado, marked by two separate shrines. The cemetery is an unlikely site of devotion for tens of thousands of people dating back to the late 1930s. What draws people to this place and who was Juan Soldado?

The place is Tijuana, near Mexico’s border with the United States. The time is the present day. In the morning hours Virginia begins setting up her stand in front of Panteón Numero Uno. Also known as the old Puerta Blanca Cemetery because of the white arch at its entrance, the panteón is located on Avenida Venustiano Carranza in a residential neighborhood and receives hundreds of visitors per day. Besides the occasional breaks for family functions and holidays, for over 40 years Virginia has been a loyal sentinel manning her post: a small curio stand right outside the white arch of the graveyard. Besides the usual rosaries and standard religious icons, Virginia specializes in items featuring the image of a young man in a green shirt and green hat. Some of her most popular items are plaster-cast busts of this person, some of them painted with overarching eyebrows and pink lips, appearing almost comical. A keychain with this young man’s face will set a person back 18 pesos, about as much as a small bag of street churros available at a neighboring food vendor. The image found on many items in Virginia’s stand is that of Juan Soldado, who in life was known as Juan Castillo Morales. Virginia and other devotees often refer to him affectionately as “Juanito,” “Little Juan,” or “El Soldadito,” “the little soldier.” Panteón Numero Uno contains both the place of death and the grave of Juan Soldado, marked by two separate shrines. The cemetery is an unlikely site of devotion for tens of thousands of people dating back to the late 1930s. What draws people to this place and who was Juan Soldado?

Tijuana in the early 1900s was a much different place from what it is today. At the turn of the century, it was a sleepy border town with a population of only a few hundred people. The Mexican state of Baja California was still a territory then, and as it is now, Tijuana was more tied to the United States than it was to the central authority in faraway Mexico City. Tijuana started to boom in the 1920s with the enactment of the 18th Amendment to the US Constitution which prohibited the manufacture, transportation, and sale of alcoholic beverages. Americans crossed the border to drink and engage in other illicit activities and the town grew to accommodate the Americans’ vices. The crown jewel of the Tijuana gambling and bar scene was the opulent Agua Caliente Casino and Hotel which opened in 1928. It had a championship golf course, a racetrack, tennis courts, spas, various entertainment venues and even its own private airstrip to fly in Hollywood elites and European royalty. American actress Rita Hayworth was discovered at the Agua Caliente, performing in a stage show. The operation was so lavish and impressive that American mobster Bugsy Siegal used it as an inspiration for his own operation in Las Vegas and thus it served as the impetus for the development of the Las Vegas Strip. One of the partners in the resort was Abelardo Rodriguez, the Military Commander and Governor of the Baja California Territory and future president of Mexico. The Agua Caliente employed thousands of Mexicans until two things happened: 1. The Twenty-First Amendment to the US Constitution ended Prohibition in 1933, and 2. The President of Mexico, Lázaro Cárdenas, made gambling illegal in all Mexican states and territories in 1935. The casinos and card rooms and many of the bars closed by the late 1930s, including the Agua Caliente, causing labor unrest in Tijuana due to the resulting high unemployment. Once a destination for people from all over Mexico looking for work and new opportunities, the city fell on dark times with much civil strife because of the catastrophic changes to the economy. The Mexican president made sure that there was a strong military presence in Tijuana to quell any popular uprisings. Among the members of the army stationed at this unruly border town was a young private named Juan Castillo Morales, the future Juan Soldado, or Juan the Soldier.

Historians, folklorists and devotees know little about the early life of Juan Castillo Morales. Some believe that he was born in 1914 and some think he was 20 years old at the time of his death, making his birth year 1918. Most researchers agree that he was born in the state of Jalisco, in west-central Mexico. Castillo seemed to be nothing other than an ordinary soldier until the events of February 1938. On February 13th an 8-year-old girl named Olga Camacho Martínez disappeared on her way to the store. Her mother called the police to affect a search, but by sundown the police came up empty-handed. Accounts vary widely as to what happened next. Some say that the strangled and violated body of Olga Camacho was discovered near Tijuana’s military barracks. Juan Soldado’s superior officer, Jesse Cardoza, asked Juan to retrieve the body. People who witnessed Juan gather up the body accused him of being the little girl’s murderer. In some stories Cardoza is the one responsible to what happened to Olga. In other stories it was another high-ranking official. In whatever version, Juan Castillo Morales ends up being framed for a crime he didn’t commit. Whether innocent or guilty, the angry Tijuana citizenry, already in a state of stress due to the socio-economic situation in the town, focused their anger and frustrations on the young army private from Jalisco. The

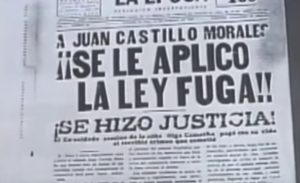

Historians, folklorists and devotees know little about the early life of Juan Castillo Morales. Some believe that he was born in 1914 and some think he was 20 years old at the time of his death, making his birth year 1918. Most researchers agree that he was born in the state of Jalisco, in west-central Mexico. Castillo seemed to be nothing other than an ordinary soldier until the events of February 1938. On February 13th an 8-year-old girl named Olga Camacho Martínez disappeared on her way to the store. Her mother called the police to affect a search, but by sundown the police came up empty-handed. Accounts vary widely as to what happened next. Some say that the strangled and violated body of Olga Camacho was discovered near Tijuana’s military barracks. Juan Soldado’s superior officer, Jesse Cardoza, asked Juan to retrieve the body. People who witnessed Juan gather up the body accused him of being the little girl’s murderer. In some stories Cardoza is the one responsible to what happened to Olga. In other stories it was another high-ranking official. In whatever version, Juan Castillo Morales ends up being framed for a crime he didn’t commit. Whether innocent or guilty, the angry Tijuana citizenry, already in a state of stress due to the socio-economic situation in the town, focused their anger and frustrations on the young army private from Jalisco. The  father of the murdered little girl belonged to one of the major labor unions in Tijuana and some thought that Olga’s murder was instigated by government forces which opposed the power of the local labor unions. A mob comprised of labor unionists, communists, anarchists and anyone else who took issue with the territorial government and the Mexican military gathered outside the police station where Juan Soldado was being held in temporary custody pending military trial. The mob grew over the course of two days and eventually set fire to the police station and Tijuana’s City Hall, and prevented firefighters from putting out the blazes. A state of anarchy existed in Tijuana and the local authorities transferred power over to the Mexican army. The military clamped down, jailed or shot some of the protestors, but had a tenuous hold over the town. The military leaders figured that the only way to placate the mobs was for them to sacrifice Juan Soldado, no matter if he was innocent or guilty. After a farcical military trial, Juan Castillo Morales was court-martialed and scheduled to be executed. To the angry mobs, this could not happen fast enough. While transporting their prisoner, some military officials encouraged Juan to flee, and he did. The whole point of this was for them to shoot Juan in the back as he ran away. Shooting him while he supposedly was trying to escape ended any sort of delay that arranging for a formal firing squad would have entailed. Instead of dragging the situation out for even one more day, the situation ended in an instant. With the death of Juan Castillo Morales, the mobs went home.

father of the murdered little girl belonged to one of the major labor unions in Tijuana and some thought that Olga’s murder was instigated by government forces which opposed the power of the local labor unions. A mob comprised of labor unionists, communists, anarchists and anyone else who took issue with the territorial government and the Mexican military gathered outside the police station where Juan Soldado was being held in temporary custody pending military trial. The mob grew over the course of two days and eventually set fire to the police station and Tijuana’s City Hall, and prevented firefighters from putting out the blazes. A state of anarchy existed in Tijuana and the local authorities transferred power over to the Mexican army. The military clamped down, jailed or shot some of the protestors, but had a tenuous hold over the town. The military leaders figured that the only way to placate the mobs was for them to sacrifice Juan Soldado, no matter if he was innocent or guilty. After a farcical military trial, Juan Castillo Morales was court-martialed and scheduled to be executed. To the angry mobs, this could not happen fast enough. While transporting their prisoner, some military officials encouraged Juan to flee, and he did. The whole point of this was for them to shoot Juan in the back as he ran away. Shooting him while he supposedly was trying to escape ended any sort of delay that arranging for a formal firing squad would have entailed. Instead of dragging the situation out for even one more day, the situation ended in an instant. With the death of Juan Castillo Morales, the mobs went home.

Many people saw through the miscarriage of justice and believed the whole time that someone either higher up in the military or in the territorial government killed the little girl and framed the young private. Out of respect for the young soldier, people started to pile rocks on the spot where Juan Castillo fell from his bullet wounds. The military, not wanting a martyr on their hands, cleaned away the stone pile and washed away any remaining blood that was still on the pavement. The day after they did this, according to many eyewitnesses, the blood returned to the pavement. The military scrubbed it down again, and the blood appeared the next day as before. As word spread throughout Tijuana of the returning blood, many people began to visit the site of the impromptu execution. The curious also began visiting the grave of Juan Castillo and claimed to experi ence many supernatural occurrences in the cemetery near the young soldier’s final resting place. Dozens of people claimed to see blood ooze from Juan’s crypt, while others claimed to hear ghostly proclamations of innocence and other assorted wailings. Several witnesses even claimed to see a ghostly honor guard marching in the cemetery. As stories spread throughout Tijuana of the otherworldly happenings surrounding this young man’s death and gravesite, popular opinion shifted, and many people started to believe that Juan Soldado had died an innocent man.

ence many supernatural occurrences in the cemetery near the young soldier’s final resting place. Dozens of people claimed to see blood ooze from Juan’s crypt, while others claimed to hear ghostly proclamations of innocence and other assorted wailings. Several witnesses even claimed to see a ghostly honor guard marching in the cemetery. As stories spread throughout Tijuana of the otherworldly happenings surrounding this young man’s death and gravesite, popular opinion shifted, and many people started to believe that Juan Soldado had died an innocent man.

To many believers, if a person is killed for a crime he did not commit, he will enjoy a position in heaven closer to God. Many people started to go to the Puerta Blanca Cemetery not just in hopes of experiencing something supernatural, but to ask the spirit of Juan Soldado to help them with desperate conditions and situations. As more and more people visited the panteón asking for assistance or begging for a miracle, it slowly transformed into a place of pilgrimage. Two small shrines spontaneously grew, one around Juan Soldado’s final resting place and one around the site of his execution. As is typical for shrines in Mexico, these are full of small offerings, candles, flowers and ex voto plaques from devotees. The ex votos are written testimonies for prayers answered sometimes accompanied by a descriptive picture. A small metal strongbox sits in the middle of the graveside shrine to accept small monetary donations for the upkeep of the two shrines. The shrine gets no financial assistance or help of any kind from the Catholic Church because the Church does not recognize Juan Soldado as a saint.

Why do people visit the shrines and what miracles do they ask from this reluctant folk saint? As with other folk saints throughout Mexico, like the Santa Muerte ( https://mexicounexplained.com//the-santa-muerte-death-respected/)or Jesus Malverde (https://mexicounexplained.com//jesus-malverde-rogue-or-saint/ ), people go to Juan Soldado when traditional Catholic saints no longer work for them. Many people petition Juanito when their situations are hopeless. Generally, though, people pray to him when a relative is incarcerated or for safe crossing into the United States for themselves or someone they know. In the more than seven decades of the Juan Soldado phenomenon El Soldadito has been credited with curing illnesses, resolving financial problems, interceding in matters of love and helping people with overcoming serious addiction. He even has a special feast day, just like a fully recognized Catholic saint, and that day is June 24th. While some people come to this small cemetery from all over Mexico, Juan Soldado is more of a regional saint, drawing most of his devotion from the people of northern Mexico and the US state of California. As long as the comfort and miracles continue, Juan Soldado will soldier on.

Why do people visit the shrines and what miracles do they ask from this reluctant folk saint? As with other folk saints throughout Mexico, like the Santa Muerte ( https://mexicounexplained.com//the-santa-muerte-death-respected/)or Jesus Malverde (https://mexicounexplained.com//jesus-malverde-rogue-or-saint/ ), people go to Juan Soldado when traditional Catholic saints no longer work for them. Many people petition Juanito when their situations are hopeless. Generally, though, people pray to him when a relative is incarcerated or for safe crossing into the United States for themselves or someone they know. In the more than seven decades of the Juan Soldado phenomenon El Soldadito has been credited with curing illnesses, resolving financial problems, interceding in matters of love and helping people with overcoming serious addiction. He even has a special feast day, just like a fully recognized Catholic saint, and that day is June 24th. While some people come to this small cemetery from all over Mexico, Juan Soldado is more of a regional saint, drawing most of his devotion from the people of northern Mexico and the US state of California. As long as the comfort and miracles continue, Juan Soldado will soldier on.

One thought on “Juan Soldado: Folk Saint of Migrants and the Wrongly Accused”

Huh?! What an interesting story, thank you for adding the historical context of the Tijuana. Now I am curious to see the shrine for myself