Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

Sonora, Mexico is a vast land of jagged canyons, whispering winds, and ancient secrets. Within this place lies a story that has tantalized explorers, historians, and pattern recognition specialists for nearly a century. It is the tale of the “Lost City of Giants,” a supposed subterranean metropolis unearthed in the 1930s by an intrepid American adventurer named Paxson C. Hayes. According to the story, Hayes stumbled upon a vast network of caves housing the mummified remains of a race of blond-haired behemoths, towering between 7 and 8 feet tall, alongside their diminutive pygmy counterparts. Accompanying these mummies were artifacts of breathtaking antiquity including stone tools dated to 94,000 years ago, intricately woven burial robes adorned with geometric patterns, and beehive-shaped stone dwellings. This discovery promised to rewrite the annals of human history.

Sonora, Mexico is a vast land of jagged canyons, whispering winds, and ancient secrets. Within this place lies a story that has tantalized explorers, historians, and pattern recognition specialists for nearly a century. It is the tale of the “Lost City of Giants,” a supposed subterranean metropolis unearthed in the 1930s by an intrepid American adventurer named Paxson C. Hayes. According to the story, Hayes stumbled upon a vast network of caves housing the mummified remains of a race of blond-haired behemoths, towering between 7 and 8 feet tall, alongside their diminutive pygmy counterparts. Accompanying these mummies were artifacts of breathtaking antiquity including stone tools dated to 94,000 years ago, intricately woven burial robes adorned with geometric patterns, and beehive-shaped stone dwellings. This discovery promised to rewrite the annals of human history.

Imagine this: The year was 1935, and the world was reeling from the Great Depression, with eyes fixed on economic woes and the gathering storm of World War II. Yet, for a brief, electrifying moment, Hayes’ claims dominated headlines from the New York Times to local news outlets in Arizona. The story evoked biblical echoes of Nephilim and Goliath, blending Native American folklore with the era’s fascination for lost civilizations. Yaqui Indian legends, passed down through generations, spoke of fair-skinned “giants” who once roamed the Copper Canyon region, clashing with indigenous tribes before vanishing into the earth. However, was this a genuine archaeological bombshell or a product of Depression-era sensationalism? In this episode of Mexico Unexplained we’ll balance the scales: examining the compelling eyewitness accounts and cultural lore that fuel belief in the giants, against the rigorous  scientific scrutiny that labels it folklore or outright hoax. Drawing from historical newspapers, modern analyses, and parallel discoveries across the Americas, we will examine why the Sonora saga endures—not just as a mystery, but as a mirror to our enduring hunger for the extraordinary and unexplained.

scientific scrutiny that labels it folklore or outright hoax. Drawing from historical newspapers, modern analyses, and parallel discoveries across the Americas, we will examine why the Sonora saga endures—not just as a mystery, but as a mirror to our enduring hunger for the extraordinary and unexplained.

Charles Paxson Hayes was no stranger to adventure. Born in 1892 in Omaha, Nebraska, to a prominent physician, Hayes cut his teeth on tales of the Wild West and exotic expeditions. By the 1920s, he had reinvented himself as an “ethnologist” and herpetologist—a snake expert—whose passions led him deep into Mexico’s untamed wilderness. His expeditions often blended legitimate fieldwork with showmanship; in 1930, newspapers buzzed about his narrow escape from a boa constrictor that cracked his ribs during a Mexican jaunt.

Hayes was a storyteller at heart, lecturing to Boy Scouts on reptiles and captivating audiences with yarns of ancient wonders. It was during one such snake-hunting foray into Yaqui territory, in the early 1930s, that Hayes first heard the whispers. The Yaqui, a resilient indigenous people of Sonora, guarded oral histories of the “Hawi” or “giants.” They described the Hawi as tall, light-haired warriors who descended from the north millennia ago, building stone cities before a cataclysmic flood or war drove them underground. These beings, the legends claimed, stood head and shoulders above ordinary men, wielding massive axes and trumpets carved from soapstone. Intrigued, Hayes mounted multiple expeditions, culminating in what he described as his “fifth” venture by 1937. The site was a blind canyon, approximately 450 miles inland from Hermosillo, near the awe-inspiring Copper Canyon, which is deeper than the Grand Canyon and riddled with uncharted caverns. Hayes and his partner, G.C. Barnes, navigated treacherous terrain, guided by Yaqui informants wary of outsiders. What they allegedly found defied comprehension: a cave complex rivaling New Mexico’s Carlsbad Caverns in scale but transformed into a subterranean pueblo. Beehive-shaped huts of volcanic rock dotted the chambers, connected by passages lined with petroglyphs depicting towering figures hunting mammoths. Deeper still lay burial niches, sealed with yucca-fiber mats and volcanic ash layers. “We dug down to volcanic ash,” Hayes recounted in a 1936 interview with the Spokane Daily Chronicle. “Below that were the burial baskets, made of mats woven from fiber and bound with twisted yucca rope.”

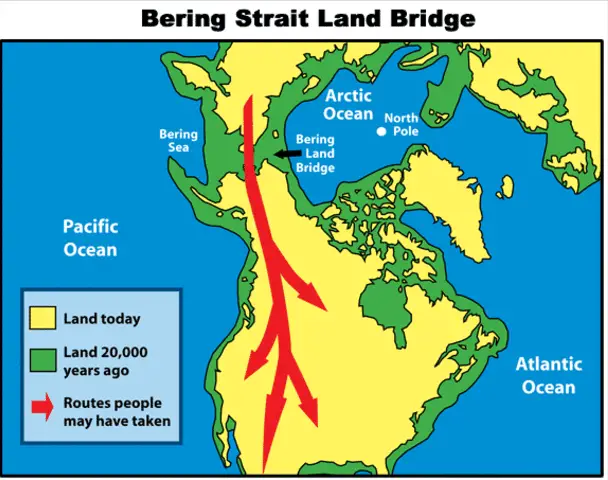

In those burial baskets were 34 mummified remains: nine intact mummies averaging 7 feet 6 inches, with one skeleton stretching a full 8 feet. Their hair, preserved by the arid conditions, was a startling Nordic blond which, of course, is uncharacteristic of traditional Mesoamerican peoples. Beside them huddled smaller figures, pygmies no taller than 3 feet, suggesting a symbiotic society of extremes. Artifacts abounded: bloody axes etched with pyramid motifs, carved mastodon bones, four-legged stools, and robes dyed in powder-blue hues with latch-hook designs hinting at trans-Pacific influences. Hayes’ narrative painted a vivid pre-Clovis civilization, predating known American settlements by tens of thousands of years. He speculated these “supermen” were ancient migrants, perhaps from the lost continent of Atlantis or ancient Eurasia, whose advanced tools, which were dated via crude stylistic analysis to 13,000–94,000 years old, challenged the Bering Strait  migration model. Returning to the U.S., Hayes paraded relics before Seri Indian chiefs on Tiburón Island, who recoiled in recognition, and even smuggled a Mexican boa constrictor as a trophy. By 1937, he and Barnes presented a burial robe and stool to the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., where officials reportedly expressed “amazement” at the 6-and-a-half-foot mummies from 18 scattered caves spanning 450 square miles.

migration model. Returning to the U.S., Hayes paraded relics before Seri Indian chiefs on Tiburón Island, who recoiled in recognition, and even smuggled a Mexican boa constrictor as a trophy. By 1937, he and Barnes presented a burial robe and stool to the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., where officials reportedly expressed “amazement” at the 6-and-a-half-foot mummies from 18 scattered caves spanning 450 square miles.

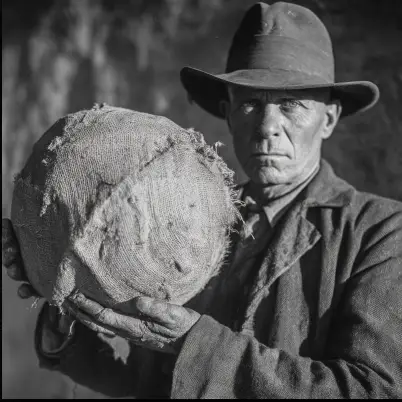

Grainy but evocative photographs from the era show Hayes cradling a massive, gourd-protected skull, its jaw disproportionately wide. Published in the San Jose News on December 31, 1935, the image bore the caption: “Paxson Hayes, explorer, studies the head of a giant mummy discovered by him in a deep cave hitherto unexplored regions of Sonora, Mexico.”

These visuals, coupled with Hayes’ charismatic lectures on “an ancient race of supermen,” ignited public fervor. For believers, it was vindication of suppressed truths; for skeptics, a prelude to disappointment.

To understand the allure of Hayes’ discovery, one must immerse themselves in the Yaqui worldview. The Yaqui people have inhabited Sonora for over 1,000 years, their cosmology weaving giants into the fabric of creation. Oral epics like the “Deer Dance” and “Pascola” rituals reference the Surem—dwarf-like ancestors—and their foes, the enormous “Hawia” or “giant people,” who wielded thunderous weapons and built cliffside fortresses. These beings, often depicted as fair-skinned invaders from the sea or stars, clashed with the Yaqui in primordial wars, their bones later interred in sacred caves to appease earth spirits. Anthropologists like Dane and Mary Coolidge, who lived among the Seri, who are neighbors to the Yaqui, in the 1930s, documented parallel tales on Tiburón Island about “white giants” discussed in Mexico Unexplained episode number 145 https://youtu.be/O-ozeWDGo2M .

The ancient stories of the indigenous should not be dismissed as mere fantasy. They could very well encode historical migrations, climatic upheavals, and encounters with taller groups, perhaps proto-Nahua or even Paleo-Siberian wanderers with lighter features from vitamin D deficiencies in northern latitudes. Proponents argue Hayes tapped into a genuine cultural memory. Richard J. Dewhurst, in his 2014 book The Ancient Giants Who Ruled America, cites Sonora as part of a continental pattern to include: red-haired Lovelock Cave mummies in Nevada, 9-foot skeletons in California’s Catalina Island burials, and 10-foot remains in West Virginia mounds. Dewhurst posits a “lost race” of elongated crania peoples, their remains suppressed to uphold Eurocentric timelines. Hayes’ blond giants, with double rows of teeth and pyramid-etched robes, align with these anomalies, suggesting diffusion from Old World megalith builders.

Modern media amplifies this perspective. A 2025 episode of Ancient Aliens dramatizes Hayes’ find as “mummified giants unearthed in Mexico,” linking it to Anunnaki lore and extraterrestrial engineering. Blogs like Greater Ancestors and Ghost Hunting Theories pore over yellowed clippings, decrying the Smithsonian’s “cover-up.” For these voices, the giants represent marginalized histories or indigenous knowledge dismissed by modern science, much like the Hopewell and Adena mound builders once derogated as “lost white races.” Yet, cultural relativism cuts both ways. Yaqui elders today, consulted by researchers, emphasize the metaphorical nature of giant tales: symbols of imbalance, where the giants’ vice of hubris leads to their downfall. No oral tradition mandates literal 8-foot skeletons; instead, they warn against exploiting sacred sites, a taboo Hayes may have breached.

Modern media amplifies this perspective. A 2025 episode of Ancient Aliens dramatizes Hayes’ find as “mummified giants unearthed in Mexico,” linking it to Anunnaki lore and extraterrestrial engineering. Blogs like Greater Ancestors and Ghost Hunting Theories pore over yellowed clippings, decrying the Smithsonian’s “cover-up.” For these voices, the giants represent marginalized histories or indigenous knowledge dismissed by modern science, much like the Hopewell and Adena mound builders once derogated as “lost white races.” Yet, cultural relativism cuts both ways. Yaqui elders today, consulted by researchers, emphasize the metaphorical nature of giant tales: symbols of imbalance, where the giants’ vice of hubris leads to their downfall. No oral tradition mandates literal 8-foot skeletons; instead, they warn against exploiting sacred sites, a taboo Hayes may have breached.

From the outset, Hayes’ claims raised red flags. No coordinates were provided for the cave. Hayes cited “protection from looters,” but critics saw evasion. Artifacts like the burial robe and stool, paraded at the Smithsonian in 1937, vanished into archives without cataloging or peer review. The institution’s annual report mentions Hayes donating snakes, not giants.

Aleš Hrdlička, Smithsonian curator of anthropology, debunked similar “giant” reports in 1934 as “the will to believe,” attributing them to misidentified megafauna bones or pathological tallness otherwise known as “gigantism” from pituitary disorders.

Hayes himself embodied the era’s pseudoscience. Photographs of the “giant skull” were most likely staged. The gourd helmet and disproportionate features suggest props, akin to the 1869 Cardiff Giant, a 10-foot gypsum statue buried and “discovered” for profit. Newspaper hype fueled the fire. For example, the Berkeley Daily Gazette in 1937 gushed about blond “supermen,” but follow-ups evaporated, a hallmark of yellow journalism during economic despair.

Broader patterns confirm skepticism. Across the Americas, “giant” discoveries follow a template of exaggeration. In Nevada’s Lovelock Cave, Paiute legends of red-haired Si-Te-Cah cannibals led to 1911 excavations yielding 6–7-foot skeletons which were taller than average but human, misidentified amid tourism hype.

Ohio’s Serpent Mound unearthed a 7-foot skeleton in the 1890s, but postcards exaggerated it; modern digs reveal average statures.

A 2016 study in Historical Biology traces this to prehistoric vertebrate misinterpretations: mammoth femurs as human thighs, elephant skulls as cyclopean heads.

These alleged finds follow a recurring pattern: initial buzz, no verifiable relics, and scientific consensus favoring mundane explanations. Anthropologist Sheilagh Brooks’ 1984 analysis of Nevada’s Reid Collection—touted as 9-and-a-half-foot giants—revealed standard sizes.

The equivalent of the Smithsonian is Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History or INAH. No publicly disclosed expedition by INAH has relocated Hayes’ cave, despite Copper Canyon being thoroughly mapped since the 1960s. Conspiracy claims of Smithsonian or INAH suppression, popularized by Dewhurst and Ancient Aliens, crumble under scrutiny. The Smithsonian’s “giant denial” stems from Hrdlička’s 1934 paper, not malice; records show thousands of Native skeletons cataloged and described, none anomalous.

A 2020 Columbus Dispatch column notes newspapers debunking hoaxes as early as 1905, with Ohio’s “giant” gravel pit skeleton measuring just 5 feet 8 inches tall.

In 2025 the giants refuse to stay buried. YouTube’s “Search for the Lost Giants” revisited Sonora in 2014, interviewing descendants who dismissed Hayes as a meddler, yet the series uncovered a 1930 Milwaukee Sentinel clip about “giant remains” in Sayopa, Sonora, echoing Hayes but unlinked.

In 2025 the giants refuse to stay buried. YouTube’s “Search for the Lost Giants” revisited Sonora in 2014, interviewing descendants who dismissed Hayes as a meddler, yet the series uncovered a 1930 Milwaukee Sentinel clip about “giant remains” in Sayopa, Sonora, echoing Hayes but unlinked.

Podcasts like “Sasquatch Chronicles” weave it all into Bigfoot lore, while TikTok virals mash it with AI-generated “giant cave footage.” Yet, balanced voices prevail. Jason Colavito’s blog critiques “Search for the Lost Giants” as pseudohistory, tracing Hayes to 19th-century frauds like P.T. Barnum. A 2024 NDTV report on a reexamination of Nevada’s Lovelock Cave notes ongoing digs yielding no giants, only Paiute artifacts.

Social media amplifies division. Pro-giant threads on Reddit decry “shrunk humans” post-1800s and Smithsonian plots, while skeptics cite osteological basics: square-cube law limits human height to about 9 feet without collapse. A 2016 psychology study links giant belief to anti-science attitudes and religiosity.

The Lost City of Giants endures not for lack of debunking, but for its poetic resonance. Hayes’ Sonora saga—whether embellished memoir or outright fabrication—captures humanity’s longing for origins grander than textbooks allow. Believers see silenced indigenous wisdom and elite cover-ups; scientists see a cautionary tale of confirmation bias and media mischief. In truth, it bridges both: a reminder that giants lurk in us all, in the stories we tell to make sense of the unknown.

The Lost City of Giants endures not for lack of debunking, but for its poetic resonance. Hayes’ Sonora saga—whether embellished memoir or outright fabrication—captures humanity’s longing for origins grander than textbooks allow. Believers see silenced indigenous wisdom and elite cover-ups; scientists see a cautionary tale of confirmation bias and media mischief. In truth, it bridges both: a reminder that giants lurk in us all, in the stories we tell to make sense of the unknown.

As Copper Canyon’s winds erode the canyons further, perhaps a real expedition will rediscover Hayes’ cave without blond mummies, but rich in Yaqui heritage. Until then, the giants of Sonora teach a humbling lesson: the greatest mysteries aren’t in the bones, but in why we crave them. In an age of deepfakes and echo chambers, may we approach such legends with the balance Hayes himself lacked with equal parts wonder and rigor.

REFERENCES

- “Finds Ancient City in Sonora, Mexico; P.C. Hayes Believes Community in Blind Canyon Dates Back 12,000 Years or More.” New York Times, January 27, 1935. https://www.nytimes.com/1935/01/27/archives/finds-ancient-city-in-sonora-mexico-pc-hayes-believes-community-in.html.

nytimes.com

- Coolidge, Dane, and Mary Roberts Coolidge. The Last of the Seris. New York: E. P. Dutton & Co., 1939.