Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

Martín Ocelotl, a Nahua priest and diviner born in 1496 in Chinantla, Puebla, stands as a pivotal yet obscure figure in Mexico’s early colonial history. His life, spanning the twilight of the Aztec Empire and the dawn of New Spain, embodies the cultural collision between indigenous traditions and Spanish conquest. Known for his alleged shapeshifting abilities, prophetic visions, and defiance of the Catholic Church, Ocelotl’s story—culminating in his 1536 trial by the nascent Mexican Inquisition—offers a window into the resilience and adaptation of Nahua spirituality under colonial rule. In this episode we will explore his origins, rise to influence, trial, and enigmatic disappearance, drawing on historical records to tell the story of a man who bridged two worlds while challenging the forces that sought to erase his own.

Martín Ocelotl, a Nahua priest and diviner born in 1496 in Chinantla, Puebla, stands as a pivotal yet obscure figure in Mexico’s early colonial history. His life, spanning the twilight of the Aztec Empire and the dawn of New Spain, embodies the cultural collision between indigenous traditions and Spanish conquest. Known for his alleged shapeshifting abilities, prophetic visions, and defiance of the Catholic Church, Ocelotl’s story—culminating in his 1536 trial by the nascent Mexican Inquisition—offers a window into the resilience and adaptation of Nahua spirituality under colonial rule. In this episode we will explore his origins, rise to influence, trial, and enigmatic disappearance, drawing on historical records to tell the story of a man who bridged two worlds while challenging the forces that sought to erase his own.

Ocelotl was born into a prominent family in Chinantla, a fertile region in the modern-day Mexican state of Puebla, during the height of the Aztec Empire. His name, meaning “jaguar” in Nahuatl, carried symbolic weight, evoking the fierce, elusive feline revered as a nahual, a spiritual alter-ego capable of shapeshifting in Nahua cosmology discussed in Mexico Unexplained episode number 36: https://youtu.be/sN5xDKhU4WY . His father, a pochtecatl, was a member of the elite merchant class, the pochteca, who traversed Mesoamerica’s trade routes, dealing in luxury goods like quetzal feathers, cacao, and obsidian. These merchants were not mere traders but also diplomats and informants, wielding significant social influence. For more information about the pochteca, please see Mexico Unexplained Episode number 102: https://youtu.be/0ChbTGatZDQ Ocelotl’s mother, a tlamacazqui or priestess, was a spiritual figure skilled in divination, healing, and rituals invoking deities like Tezcatlipoca, the god of providence and sorcery. Her role immersed young Ocelotl in the sacred practices of the Nahua, from reading the 260-day tonalpohualli calendar to performing bloodletting ceremonies. Raised in this environment, Ocelotl was groomed for a priestly role or for some other form of leadership. By his teens, he apprenticed under local priests and shamans, mastering the intricate rituals that sustained the Aztec cosmos. These priests were multifaceted and served as astronomers, healers, and keepers of sacred knowledge. They used tools like bark-paper codices and amulets to commune with gods. Ocelotl learned to interpret celestial omens, craft talismans, and perform rites for rain or fertility. Historical accounts suggest he was particularly adept as a tonalpouhqui, a diviner who could read the sacred calendar to predict events like eclipses or harvests. Rumors also swirled of his nahualism, the ability to transform into a jaguar or wild cat, a practice blending shamanic trance with cultural metaphor. Whether literal or symbolic, these tales marked him as a figure of spiritual potency in a society where the divine permeated daily life. Ocelotl’s rise would come only after a great “fall.”

The arrival of Hernán Cortés in 1519 upended Ocelotl’s world. At 23, he was summoned to Tenochtitlan, the Aztec capital, to advise Emperor Moctezuma II amid omens of bearded strangers from the east. The Aztec elite, steeped in prophecy, feared these signs heralded the end of the Fifth Sun, the current cosmic era in which they lived. In Moctezuma’s court, Ocelotl reportedly delivered a grim vision: Tenochtitlan would fall not in glory but in ruin, its pyramids toppled, and its people thoroughly subjugated. This prophecy, recorded in later Spanish chronicles, enraged Moctezuma, who saw it as treasonous. Ocelotl was imprisoned beneath the Templo Mayor, facing potential sacrifice. However, the chaos of the 1521 Spanish siege, marked by smallpox, betrayal, and cannon fire allowed his escape as the city crumbled. Fleeing to Texcoco, a cultural hub of the Triple Alliance, Ocelotl reinvented himself as a curandero, or healer. The fall of Tenochtitlan had shattered the Aztec political order, but the spiritual needs of the Nahua people persisted. Operating from a modest home, he offered divinations, herbal remedies, and rituals to address ailments from infertility to spiritual malaise. His success drew a following from farmers and widows to even local nobles who credited him with summoning rain or curing the sick. Ocelotl’s wealth grew, not from exploitation but from a communal ethos: he shared maize with the poor and gifted amulets to allies, building a network of loyalty that alarmed the Spanish authorities. In Texcoco, Ocelotl established a clandestine school, teaching young Nahuas the old ways including hymns in the Nahuatl language, calendar readings, and ancient Aztec rituals. At the same time, Ocelotl adapted to the new reality of his life under Spanish rule. This school was less a formal institution than a covert gathering, blending Aztec practices with emerging syncretism, or blending of the two worlds. Catholic saints began to merge with indigenous deities in his teachings, a pragmatic response to the evangelizing friars flooding New Spain. Ocelotl’s influence grew, positioning him as a leader of a quiet resistance, preserving ancient Nahua identity under the guise of adaptation.

The arrival of Hernán Cortés in 1519 upended Ocelotl’s world. At 23, he was summoned to Tenochtitlan, the Aztec capital, to advise Emperor Moctezuma II amid omens of bearded strangers from the east. The Aztec elite, steeped in prophecy, feared these signs heralded the end of the Fifth Sun, the current cosmic era in which they lived. In Moctezuma’s court, Ocelotl reportedly delivered a grim vision: Tenochtitlan would fall not in glory but in ruin, its pyramids toppled, and its people thoroughly subjugated. This prophecy, recorded in later Spanish chronicles, enraged Moctezuma, who saw it as treasonous. Ocelotl was imprisoned beneath the Templo Mayor, facing potential sacrifice. However, the chaos of the 1521 Spanish siege, marked by smallpox, betrayal, and cannon fire allowed his escape as the city crumbled. Fleeing to Texcoco, a cultural hub of the Triple Alliance, Ocelotl reinvented himself as a curandero, or healer. The fall of Tenochtitlan had shattered the Aztec political order, but the spiritual needs of the Nahua people persisted. Operating from a modest home, he offered divinations, herbal remedies, and rituals to address ailments from infertility to spiritual malaise. His success drew a following from farmers and widows to even local nobles who credited him with summoning rain or curing the sick. Ocelotl’s wealth grew, not from exploitation but from a communal ethos: he shared maize with the poor and gifted amulets to allies, building a network of loyalty that alarmed the Spanish authorities. In Texcoco, Ocelotl established a clandestine school, teaching young Nahuas the old ways including hymns in the Nahuatl language, calendar readings, and ancient Aztec rituals. At the same time, Ocelotl adapted to the new reality of his life under Spanish rule. This school was less a formal institution than a covert gathering, blending Aztec practices with emerging syncretism, or blending of the two worlds. Catholic saints began to merge with indigenous deities in his teachings, a pragmatic response to the evangelizing friars flooding New Spain. Ocelotl’s influence grew, positioning him as a leader of a quiet resistance, preserving ancient Nahua identity under the guise of adaptation.

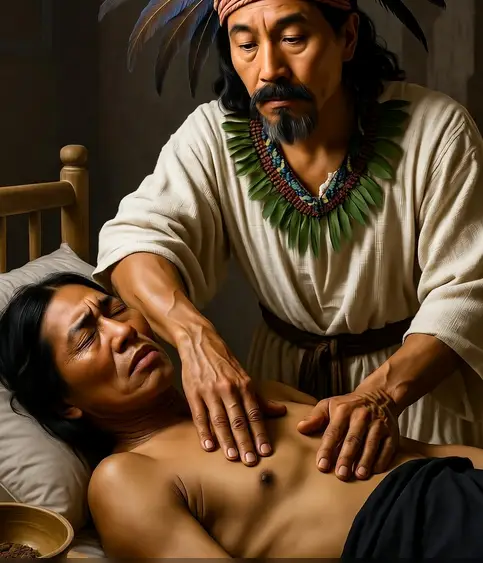

By 1525, the Spanish had consolidated control, renaming Tenochtitlan as Mexico City and imposing Catholicism through mass baptisms and friaries built on razed indigenous temples. Ocelotl, recognizing the futility of outright defiance, underwent baptism in Texcoco’s plaza, taking the Christian name Martín. This act was strategic; many Nahuas adopted Christian names while  maintaining private devotion to their gods. Martín attended Mass and learned basic Catholic doctrine, but his home remained a sanctuary for hybrid rituals. He paired prayers to Tlazolteotl, the Nahua goddess of purification, with confessions to Catholic saints, creating a spiritual blend that resonated with his followers. His growing influence drew scrutiny, however. Spanish friars, fresh from Europe’s witch-hunts, viewed indigenous healers with suspicion, equating their practices with devil worship and witchcraft. Martín’s wealth—amassed through offerings disguised as alms—and his charisma fueled envy among rivals, both indigenous and European. Informants began reporting his activities to the Franciscans, accusing him of mocking Christianity and practicing sorcery. A pivotal moment came in 1536 when Martín healed Don Pablo Xochiquentzin, the Spanish-installed cuauhtlatoani of Tenochtitlan. Pablo suffered from a spiritual and physical exhaustion, a condition Nahuas called tlalticpac tlahtocayotl. Martín’s treatment which consisted of herbal baths, chants, and an ancient ritual restored Pablo’s vigor, but the public nature of the cure drew the attention of Bishop Juan de Zumárraga, the Apostolic Inquisitor.

maintaining private devotion to their gods. Martín attended Mass and learned basic Catholic doctrine, but his home remained a sanctuary for hybrid rituals. He paired prayers to Tlazolteotl, the Nahua goddess of purification, with confessions to Catholic saints, creating a spiritual blend that resonated with his followers. His growing influence drew scrutiny, however. Spanish friars, fresh from Europe’s witch-hunts, viewed indigenous healers with suspicion, equating their practices with devil worship and witchcraft. Martín’s wealth—amassed through offerings disguised as alms—and his charisma fueled envy among rivals, both indigenous and European. Informants began reporting his activities to the Franciscans, accusing him of mocking Christianity and practicing sorcery. A pivotal moment came in 1536 when Martín healed Don Pablo Xochiquentzin, the Spanish-installed cuauhtlatoani of Tenochtitlan. Pablo suffered from a spiritual and physical exhaustion, a condition Nahuas called tlalticpac tlahtocayotl. Martín’s treatment which consisted of herbal baths, chants, and an ancient ritual restored Pablo’s vigor, but the public nature of the cure drew the attention of Bishop Juan de Zumárraga, the Apostolic Inquisitor.

Bishop Zumárraga, a Basque Franciscan appointed in 1528, was tasked with eradicating “idolatry” in New Spain. While the formal Mexican Inquisition wasn’t established until 1571, Zumárraga wielded proto-inquisitorial powers, targeting relapsed natives and suspected witches and sorcerers. In 1536, he had overseen the burning of a Nahua woman for witchcraft, setting a precedent for Martín Ocelotl’s case. That autumn, Martín was arrested, his home raided, and his ritual objects including jade amulets, gold disks, and codices were confiscated as evidence of heresy. The trial, held in a Mexico City monastery, was a spectacle of colonial anxieties. Over 20 witnesses testified, their accounts preserved in Mexico’s National Archives. A farmer claimed Martín predicted a drought’s end through dances that mocked Christian saints. A widow swore he transformed into a cat to spy on her. Rival healers accused him of having multiple wives and engaging in demonic pacts. The most damning testimony came from nobles, who linked him to Pablo’s healing, framing it as a  pagan rite. The seized artifacts, including a jade ocelot claw and eclipse-charged codices, were cataloged in pictographic inventories, by indigenous scribes, blending Nahua and European styles. Martín’s defense was shrewd. He affirmed his Catholic faith, framing his practices as visions or metaphors akin to biblical miracles. Shapeshifting, he argued, was a dream-state, not devilry; rain-calling was prayer to a universal creator. He challenged the Inquisition’s jurisdiction over natives, citing Spanish legal exemptions, and exposed inconsistencies in witness testimonies. Yet his boldest move was a cryptic prophecy: the cross would wane, and the eagle would rise, hinting at a coming indigenous resurgence. The trial stretched into the year 1537, with Martín Ocelotl enduring public floggings and extensive periods of confinement. Zumárraga, wary of sparking rebellion by executing a popular healer, consulted authorities in Spain. On February 10, 1537, Martín was found guilty of sorcery and idolatry but sentenced to perpetual imprisonment in Spain rather than death. Before his sentence, authorities paraded him around in a san benito robe, a garment made of black cloth covered with illustrations of devils and flames. Martín was then shipped across the Atlantic and he vanished from the historical record.

pagan rite. The seized artifacts, including a jade ocelot claw and eclipse-charged codices, were cataloged in pictographic inventories, by indigenous scribes, blending Nahua and European styles. Martín’s defense was shrewd. He affirmed his Catholic faith, framing his practices as visions or metaphors akin to biblical miracles. Shapeshifting, he argued, was a dream-state, not devilry; rain-calling was prayer to a universal creator. He challenged the Inquisition’s jurisdiction over natives, citing Spanish legal exemptions, and exposed inconsistencies in witness testimonies. Yet his boldest move was a cryptic prophecy: the cross would wane, and the eagle would rise, hinting at a coming indigenous resurgence. The trial stretched into the year 1537, with Martín Ocelotl enduring public floggings and extensive periods of confinement. Zumárraga, wary of sparking rebellion by executing a popular healer, consulted authorities in Spain. On February 10, 1537, Martín was found guilty of sorcery and idolatry but sentenced to perpetual imprisonment in Spain rather than death. Before his sentence, authorities paraded him around in a san benito robe, a garment made of black cloth covered with illustrations of devils and flames. Martín was then shipped across the Atlantic and he vanished from the historical record.

Martín Ocelotl’s fate remains uncertain. Ship logs offer no clarity on whether he reached Seville or perished at sea. In 1540, caches of his artifacts surfaced in Tlatelolco, suggesting loyalists preserved his legacy. Nahua codices from the period mention “Ocelotl’s Echo,” a messianic figure tied to cultural revival. Historians and other scholars argue his trial galvanized underground resistance while others saw it as a catalyst for harsher inquisitorial measures, like the 1539 burning of Don Carlos of Texcoco. Ocelotl’s life reflects the syncretic heart of modern Mexico, where Catholic and indigenous traditions intertwine in practices like Day of the Dead. His trial documents, rediscovered in the 20th century, reveal a cultural tug-of-war: Spanish rigidity versus Nahua adaptability, where healing was magic and prophecy was power. In Texcoco and Puebla, oral traditions persist, tying springs and hills to his name, while elders speak of jaguar spirits guarding the night. Martín Ocelotl—priest, healer, or nahual—remains a symbol of resistance, a jaguar stalking the margins of history, reminding us that some spirits cannot be caged.

REFERENCES