Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

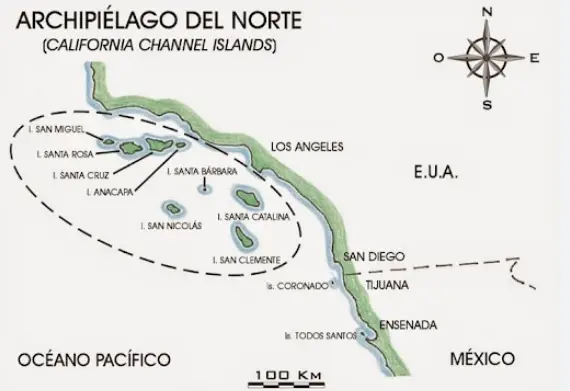

The California Channel Islands, an eight-island chain off the coast of Southern California, are a treasure of natural beauty and ecological significance. Known in Mexico as the Archipiélago del Norte, or the Archipelago of the North, these islands—San Miguel, Santa Rosa, Santa Cruz, Anacapa, Santa Barbara, San Nicolás, Santa Catalina, and San Clemente—are today part of the United States, with most forming the Channel Islands National Park and others under U.S. Navy control. Yet, a persistent rumor suggests that these islands were never properly ceded to the United States under the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which ended the Mexican War. Could these oil-rich islands, visible from California’s shores, still rightfully belong to Mexico? In this episode of Mexico Unexplained we will delve into the history of the Channel Islands, explore the treaty’s alleged ambiguity, indulge in speculative scenarios of what might have been, and ultimately resolve whether to affirm this archipelago’s status as rightful territory of the United States.

The California Channel Islands, an eight-island chain off the coast of Southern California, are a treasure of natural beauty and ecological significance. Known in Mexico as the Archipiélago del Norte, or the Archipelago of the North, these islands—San Miguel, Santa Rosa, Santa Cruz, Anacapa, Santa Barbara, San Nicolás, Santa Catalina, and San Clemente—are today part of the United States, with most forming the Channel Islands National Park and others under U.S. Navy control. Yet, a persistent rumor suggests that these islands were never properly ceded to the United States under the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which ended the Mexican War. Could these oil-rich islands, visible from California’s shores, still rightfully belong to Mexico? In this episode of Mexico Unexplained we will delve into the history of the Channel Islands, explore the treaty’s alleged ambiguity, indulge in speculative scenarios of what might have been, and ultimately resolve whether to affirm this archipelago’s status as rightful territory of the United States.

The story of the Channel Islands begins long before the ink dried on the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. For over 13,000 years, indigenous peoples called these islands home. The Chumash primarily lived in the northern islands of San Miguel, Santa Rosa, Santa Cruz, Anacapa and Tongva-related groups inhabited the southern islands of Santa Catalina and San Clemente. They navigated the Pacific in plank canoes, trading with mainland communities and thriving in a maritime culture. Spanish explorers first encountered the islands in 1542, when Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo sailed along the California coast, but colonization was minimal during the Spanish period from 1769 to 1821. During the 1600s and early 1700s the island group was a haven for British and Dutch buccaneers who preyed on the Spanish galleon trade, and stories of buried pirate treasure on the islands have lingered for centuries. The islands were considered part of Alta California, the northernmost province of Spain’s empire in the Americas, but their isolation and perceived economic worthlessness limited development.

When Mexico gained independence from Spain in 1821, the Channel Islands became part of the new nation’s Alta California territory. Mexican governance, however, faced similar challenges. The islands were sparsely populated, used mainly for fishing, sealing, and grazing. Governors issued land grants to encourage settlement: Mexican army captain Andrés Castillero received Santa Cruz in 1839, José and Carlos Carrillo got Santa Rosa in 1843, and an American named Thomas Robbins was granted Santa Catalina in 1846 on the eve of the Mexican War. These grants aimed to spark ranching operations, but logistical difficulties stymied progress.

One intriguing episode from this era was Mexico’s attempt to establish a penal colony on Santa Cruz Island in 1830. The Mexican government contracted a U.S. vessel, the Maria Ester, to transport 80 convicts from Acapulco to Alta California. When San Diego and Santa Barbara refused to accept them, 30 men were settled on Santa Cruz’s north shore, now known as Prisoners Harbor. Supplied with food and building materials, the convicts struggled against harsh conditions and a fire that destroyed their shelters. Desperate, they built rafts and fled to the mainland, miraculously surviving the perilous journey. This failed experiment, while a footnote in history, underscores Mexico’s administrative claim to the islands during its rule.

One intriguing episode from this era was Mexico’s attempt to establish a penal colony on Santa Cruz Island in 1830. The Mexican government contracted a U.S. vessel, the Maria Ester, to transport 80 convicts from Acapulco to Alta California. When San Diego and Santa Barbara refused to accept them, 30 men were settled on Santa Cruz’s north shore, now known as Prisoners Harbor. Supplied with food and building materials, the convicts struggled against harsh conditions and a fire that destroyed their shelters. Desperate, they built rafts and fled to the mainland, miraculously surviving the perilous journey. This failed experiment, while a footnote in history, underscores Mexico’s administrative claim to the islands during its rule.

By the 1840s, disease and colonial disruption had decimated the Chumash and Tongva populations, ending their millennia-long presence on the islands. When the Mexican War broke out in 1846, the Channel Islands, like the rest of Alta California, were caught in the crosshairs of a conflict that would reshape North America.

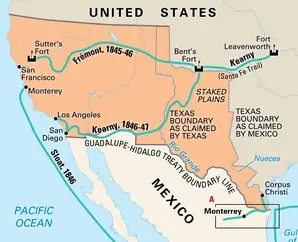

The Mexican War from 1846 to 1848 was a devastating chapter for the nation of Mexico, culminating in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, signed on February 2, 1848. The treaty ceded over 50% of Mexico’s territory to the United States, including modern-day California, Nevada, Utah, Arizona, New Mexico, and parts of other states, in exchange for $15 million and the assumption of $3.25 million in Mexican debts owed to American citizens. Article 5 of the treaty defined the new U.S.-Mexico border, tracing it from the Gulf of Mexico along the Rio Grande, across deserts, and to the Pacific Ocean, ending – quote – “at a point on the coast of the Pacific Ocean distant one marine league due south of the southernmost point of the Port of San Diego.” End quote.

This description, while precise for the mainland, has fueled speculation about the Channel Islands. The treaty does not explicitly mention the islands, leading some to argue they were overlooked in the cession. The 1847 Disturnell Map, referenced during treaty negotiations, depicted Alta California as including its coastal islands, suggesting the negotiators intended to transfer them to the U.S. However, the lack of a specific mention in Article 5 created a perceived loophole, sparking claims that the islands remained Mexican territory.

This description, while precise for the mainland, has fueled speculation about the Channel Islands. The treaty does not explicitly mention the islands, leading some to argue they were overlooked in the cession. The 1847 Disturnell Map, referenced during treaty negotiations, depicted Alta California as including its coastal islands, suggesting the negotiators intended to transfer them to the U.S. However, the lack of a specific mention in Article 5 created a perceived loophole, sparking claims that the islands remained Mexican territory.

In 1894, Mexican geographer Esteban Cházari seized on this ambiguity in a speech to the Mexican Society for Geography and Statistics, founded in 1833 as the first geographical society in the Americas. Cházari argued that the Channel Islands were – quote – “completely outside of the boundary line established by the United States” – end quote – and beyond U.S. territorial waters, which then extended only three miles from the coast. He pointed to Mexico’s land grants in the 1830s–1840s as evidence of active sovereignty, contrasting this with the U.S.’s lack of military occupation of the islands in the 1850s. Calling the treaty the result of “the most unjust of wars,” Cházari urged President Porfirio Díaz to reclaim the islands, which he believed were being “invaded by American squatters.” The Society supported his call, petitioning Díaz, but no action followed.

The ambiguity of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo inspired various groups to challenge the islands’ status. In the 1890s, Civil War veteran William Waters declared himself the “King of San Miguel Island,” resisting U.S. surveyors by citing the treaty’s vague wording. Decades later, rancher Herbert Lester echoed this defiance, proclaiming his own “kingdom” on San Miguel. Lester’s “reign” over  the island as self-appointed monarch was even featured in a 1930s photo feature in LIFE magazine. These eccentric claims by Americans were less about Mexican sovereignty and treaty interpretation and more about exploiting legal uncertainty for personal gain.

the island as self-appointed monarch was even featured in a 1930s photo feature in LIFE magazine. These eccentric claims by Americans were less about Mexican sovereignty and treaty interpretation and more about exploiting legal uncertainty for personal gain.

In the 1940s, Mexico briefly revisited the issue. President Manuel Ávila Camacho formed a commission of geographers, jurists, and historians to study potential claims to the Channel Islands. The 1944–1947 Ávila Camacho Commission produced a weighty 400-page report, delivered to President Miguel Alemán in 1947, concluding that Mexico lacked legal grounds to claim the islands. Fearing public backlash, the government classified the findings, a decision that fueled speculation and kept the rumor alive.

There were also challenges to US rule over the islands coming from Mexican-American and indigenous groups. In 1972, the Brown Berets, a Chicano activist group formed to combat anti-Mexican discrimination, occupied Santa Catalina Island for 24 days. Led by co-founder David Sánchez, the group raised the Mexican flag over the sleepy port city of Avalon, citing the treaty’s ambiguity to protest poor living conditions for Mexican-Americans. Though evicted by riot police, their action drew attention to the islands’ contested history.

There were also challenges to US rule over the islands coming from Mexican-American and indigenous groups. In 1972, the Brown Berets, a Chicano activist group formed to combat anti-Mexican discrimination, occupied Santa Catalina Island for 24 days. Led by co-founder David Sánchez, the group raised the Mexican flag over the sleepy port city of Avalon, citing the treaty’s ambiguity to protest poor living conditions for Mexican-Americans. Though evicted by riot police, their action drew attention to the islands’ contested history.

The Chumash, descendants of the islands’ original inhabitants, also invoked the vagueness of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in a 1986 legal case. Chumash plaintiff Chunie Frances Herrera argued that the islands were not formally ceded to the US and that the pre-colonial presence of the Chumash bolstered their claim. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit rejected this, affirming that – quote – “neither the United States nor Mexico has ever contested the inclusion of the islands as part of California.” – end quote.

What if the Channel Islands had remained Mexican territory? Imagine a maritime border running between California’s mainland and the islands, with Tijuana administering San Clemente and Santa Catalina. Mexico would control a strategic archipelago, rich in oil deposits that fueled a boom until the 1969 Santa Barbara Oil Spill. This could have shifted the U.S.-Mexico border northward, making the Channel Islands Latin America’s northernmost frontier. Oil production would likely be a Mexican priority, mirroring tensions seen in cross-border pollution issues, like those in Tijuana and San Diego. The islands’ proximity to Los Angeles and San Diego might have sparked diplomatic frictions, with fishing rights and maritime boundaries becoming flashpoints. Culturally, the islands could have developed as vibrant Mexican outposts, with Santa Catalina’s Avalon hosting festivals blending Chumash, Mexican, and tourist influences. The U.S. Navy’s control of San Clemente and San Nicolas would be absent, potentially altering military dynamics in the Pacific. Politically, Mexico’s retention of the islands might have emboldened nationalist movements, with the Archipiélago del Norte symbolizing resistance to the 1848 territorial losses. Chicano activists might have rallied around the islands as a reclaimed heritage, while Chumash communities could have partnered with Mexican authorities to preserve their cultural sites. However, Mexico’s logistical challenges in the 19th century—evident in the failed penal colony—suggest that developing the islands would have been difficult, potentially leaving them as sparsely populated outposts.

Despite the treaty’s ambiguity and the claims it inspired, the Channel Islands are unequivocally U.S. territory. Several factors confirm this. One is historical Intent: The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ceded all of Alta California, including its islands, as shown in the Disturnell Map. International law at the time included adjacent islands in territorial cessions unless explicitly excluded. Another factor is Mexican Inaction: Mexico never formally contested the islands’ transfer post-1848. The Ávila Camacho Commission’s 1947 report acknowledged Mexico’s weak legal position, and no  subsequent government pursued a claim. The third factor is U.S. Administration: The U.S. has governed the islands since 1848, integrating them into California. Santa Catalina became a tourist destination, San Clemente a naval base, and five islands form the Channel Islands National Park, established in 1980. The fourth factor is legal precedent: The 1986 Chunie v. Ringrose ruling affirmed U.S. sovereignty, noting no U.S.-Mexico dispute over the islands. The last factor confirming that the Channel Islands are part of the US is maritime treaty: The 1978 U.S.-Mexico Maritime Boundary Treaty explicitly placed the islands north of the maritime border, confirming U.S. jurisdiction.

subsequent government pursued a claim. The third factor is U.S. Administration: The U.S. has governed the islands since 1848, integrating them into California. Santa Catalina became a tourist destination, San Clemente a naval base, and five islands form the Channel Islands National Park, established in 1980. The fourth factor is legal precedent: The 1986 Chunie v. Ringrose ruling affirmed U.S. sovereignty, noting no U.S.-Mexico dispute over the islands. The last factor confirming that the Channel Islands are part of the US is maritime treaty: The 1978 U.S.-Mexico Maritime Boundary Treaty explicitly placed the islands north of the maritime border, confirming U.S. jurisdiction.

The rumor of Mexican ownership persists due to the treaty’s vague wording and the emotional weight of Mexico’s territorial losses. Nationalist sentiments coming from both sides of the border, amplified by figures like Cházari and the Brown Berets, keep the idea alive, as does the islands’ historical ties to Mexico’s Alta California. Yet, the legal, historical, and practical evidence is clear: the Channel Islands were ceded to the U.S. in 1848 and remain American soil. The Channel Islands’ story is one of intrigue, blending indigenous heritage, colonial ambition, and modern activism. The notion that they were overlooked in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo reflects the pain of Mexico’s 1848 defeat and the allure of reclaiming a “lost archipelago.” While speculative scenarios of Mexican control spark the imagination, the historical record—bolstered by maps, court rulings, and international agreements—confirms the islands as part of the United States. Today, as visitors hike Santa Cruz’s trails or ferry to Santa Catalina’s Avalon, they walk on land shaped by a complex past, where the echoes of Mexico’s claim linger as a fascinating footnote in the ever-evolving U.S.-Mexico border saga.

REFERENCES

- National Archives. “Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (1848).” Milestone Documents. Last modified February 8, 2022. https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/treaty-of-guadalupe-hidalgo.

- Parra, Carlos Francisco. “Mexico’s Claims to the California Channel Islands.” Nomadic Border, January 20, 2020, updated July 20, 2020. https://www.nomadicborder.com/post/mexico-s-claims-to-the-california-channel-islands.

- Vargas, Jorge A. “Mexico’s Legal Claims to the California Channel Islands: A Study of the Ávila Camacho Commission, 1944–1947.” Mexican Studies/ consumption Estudios Mexicanos 15, no. 2 (Summer 1999): 305–32