Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

This episode will examine the Mummies of Guanajuato in fact and fiction. Yes, Mexico has its mummies, but unlike mummies from Egypt and other parts of the world, these mummies are accidental and are of common people. They date from the post-Conquest era, specifically the 19th and early 20th Centuries. So, how did Mexico come to have mummies? What’s their story, and how have they captured the imagination of a country in its popular culture?

This episode will examine the Mummies of Guanajuato in fact and fiction. Yes, Mexico has its mummies, but unlike mummies from Egypt and other parts of the world, these mummies are accidental and are of common people. They date from the post-Conquest era, specifically the 19th and early 20th Centuries. So, how did Mexico come to have mummies? What’s their story, and how have they captured the imagination of a country in its popular culture?

The mummies discussed here come from the city of Guanajuato and its surroundings. Guanajuato was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site by the United Nations in 1988. The city is truly enchanting and deserves this designation. One can get lost marveling at its colonial architecture and wandering its numerous narrow side streets and alleys called callejones.

The name Guanajuato comes from the Tarascans or Purepecha and was originally called “Quanax huato,” which means “hilly place of frogs.” In pre-Hispanic times the Aztecs were here and called the area Paxtitlán, “the place of straw.” Before that, it was known as Mo-o-ti, which means “the place of minerals.” The Aztecs mined precious metals here, mostly for ornamental purposes, and to feed the market for elite items hand crafted out of metal. When the Spanish arrived in the early 1500s they heard of the Aztec mines and discovered gold for themselves in the 1540s. Soon a garrison was sent to protect the mines, a town was set up and the city became formalized as Santa Fé Real de Minas de Guanajuato in 1548. The largest mine in the area, La Valenciana, at one point was producing one third of the world’s silver and helped contribute to a bottoming out of the silver market and overall economic downturn in the 1600s. The vast wealth created by the mines helped fuel the artistic building frenzy in Guanajuato. Some of the finest examples of baroque architecture in all of Latin America can be found in the religious buildings of this place. The city also played an important role in the Mexican war of independence from Spain. The first battle of the war between the royalist forces and the insurgents led by Father Hidalgo occurred at a granary inside the city. Mining lessened in importance throughout most of the 1800s but became important again in the 1870s when Porfirio Diaz, the ruler of Mexico, encouraged foreign investment to develop more mines.

The name Guanajuato comes from the Tarascans or Purepecha and was originally called “Quanax huato,” which means “hilly place of frogs.” In pre-Hispanic times the Aztecs were here and called the area Paxtitlán, “the place of straw.” Before that, it was known as Mo-o-ti, which means “the place of minerals.” The Aztecs mined precious metals here, mostly for ornamental purposes, and to feed the market for elite items hand crafted out of metal. When the Spanish arrived in the early 1500s they heard of the Aztec mines and discovered gold for themselves in the 1540s. Soon a garrison was sent to protect the mines, a town was set up and the city became formalized as Santa Fé Real de Minas de Guanajuato in 1548. The largest mine in the area, La Valenciana, at one point was producing one third of the world’s silver and helped contribute to a bottoming out of the silver market and overall economic downturn in the 1600s. The vast wealth created by the mines helped fuel the artistic building frenzy in Guanajuato. Some of the finest examples of baroque architecture in all of Latin America can be found in the religious buildings of this place. The city also played an important role in the Mexican war of independence from Spain. The first battle of the war between the royalist forces and the insurgents led by Father Hidalgo occurred at a granary inside the city. Mining lessened in importance throughout most of the 1800s but became important again in the 1870s when Porfirio Diaz, the ruler of Mexico, encouraged foreign investment to develop more mines.

It was during this time when the government instituted a perpetual burial tax. If survivors of the buried person could not pay the tax, the body of the relative would be exhumed. It was during this time when the mummies were discovered, much to the surprise of the people responsible for enforcing the penalties of not paying the tax. The mineral-rich soils and the dryness of the climate are two conditions generally thought to have aided in the preservation of the bodies, but according to experts the soils have very little to do with this phenomenon, if anything. 100% of the bodies were recovered from above-ground crypts and only 1 in 10 have been found mummified. Although some mummies were previously embalmed, most of them, according to scientists, were preserved by the utter dryness of the air, which caused the bodies to mummify quickly. This phenomenon only occurs in one other place in Mexico, in a small region in the state of Jalisco to the west. The majority of the mummies came from exhumations done in the late 19th Century. The burial tax ended in 1958 and so no new mummies were unearthed after that time.

It was during this time when the government instituted a perpetual burial tax. If survivors of the buried person could not pay the tax, the body of the relative would be exhumed. It was during this time when the mummies were discovered, much to the surprise of the people responsible for enforcing the penalties of not paying the tax. The mineral-rich soils and the dryness of the climate are two conditions generally thought to have aided in the preservation of the bodies, but according to experts the soils have very little to do with this phenomenon, if anything. 100% of the bodies were recovered from above-ground crypts and only 1 in 10 have been found mummified. Although some mummies were previously embalmed, most of them, according to scientists, were preserved by the utter dryness of the air, which caused the bodies to mummify quickly. This phenomenon only occurs in one other place in Mexico, in a small region in the state of Jalisco to the west. The majority of the mummies came from exhumations done in the late 19th Century. The burial tax ended in 1958 and so no new mummies were unearthed after that time.

Soon after the discovery of the mummies, the naturally preserved bodies drew attention from the curious. In the late 1800s people began paying to see the mummies which were stored somewhat haphazardly in a building near the cemetery. Now considered to be the largest collection of mummies in the Western Hemisphere, the Guanajuato Mummy Museum opened in 1970 to showcase the remains behind glass for all the curiosity-seekers to see. The collection has 111 total mummies, many of them women and children. Most of the mummies have their original clothes. Many of the children are dressed up as angels or little saints for an easier entrance into the afterlife. The museum claims to have the smallest mummy in the world, that of a fetus. There are many legends surrounding why some of the mummies have contorted and twisted faces including a famous story that people were mistakenly buried alive and tried to escape their fate but died in the attempt. In 2007 a team led by a Texas State University at San Marcos professor, Jerry Melbye, examined 22 of the mummies in the Guanajuato Mummy Museum collection. The purpose of the study was to increase overall scientific and historical knowledge of the mummies. Dr. Melbye has studied mummies in Egypt’s Sahara desert, those in Mesa Verde National park in the Southwest US and specimens from Vancouver Island, British Columbia. The team’s examinations have revealed evidence of such diseases as rheumatoid arthritis, extreme anemia, and tuberculosis, sometimes severe enough to cause death. They have also found evidence of smoke inhalation, either from smoking tobacco or from working in the local mines. A number of babies in the mummy study died at a very early age, possibly from a common bacterial infection that infants in pre-industrial societies often contract when adults begin to feed them solid food that they have softened by chewing.

Soon after the discovery of the mummies, the naturally preserved bodies drew attention from the curious. In the late 1800s people began paying to see the mummies which were stored somewhat haphazardly in a building near the cemetery. Now considered to be the largest collection of mummies in the Western Hemisphere, the Guanajuato Mummy Museum opened in 1970 to showcase the remains behind glass for all the curiosity-seekers to see. The collection has 111 total mummies, many of them women and children. Most of the mummies have their original clothes. Many of the children are dressed up as angels or little saints for an easier entrance into the afterlife. The museum claims to have the smallest mummy in the world, that of a fetus. There are many legends surrounding why some of the mummies have contorted and twisted faces including a famous story that people were mistakenly buried alive and tried to escape their fate but died in the attempt. In 2007 a team led by a Texas State University at San Marcos professor, Jerry Melbye, examined 22 of the mummies in the Guanajuato Mummy Museum collection. The purpose of the study was to increase overall scientific and historical knowledge of the mummies. Dr. Melbye has studied mummies in Egypt’s Sahara desert, those in Mesa Verde National park in the Southwest US and specimens from Vancouver Island, British Columbia. The team’s examinations have revealed evidence of such diseases as rheumatoid arthritis, extreme anemia, and tuberculosis, sometimes severe enough to cause death. They have also found evidence of smoke inhalation, either from smoking tobacco or from working in the local mines. A number of babies in the mummy study died at a very early age, possibly from a common bacterial infection that infants in pre-industrial societies often contract when adults begin to feed them solid food that they have softened by chewing.

The mummy museum can engender mixed feelings. These are real people on display and the exhibit is not for the faint of heart. Many people consider the museum too morbid and skip it on their tour of the beautiful colonial city of Guanajuato. As is typical in Mexico at such tourist destinations, one can purchase most anything mummy-related outside the museum including key chains, mummy replicas, coffee mugs and barely edible mummy candy.

The mummy museum can engender mixed feelings. These are real people on display and the exhibit is not for the faint of heart. Many people consider the museum too morbid and skip it on their tour of the beautiful colonial city of Guanajuato. As is typical in Mexico at such tourist destinations, one can purchase most anything mummy-related outside the museum including key chains, mummy replicas, coffee mugs and barely edible mummy candy.

Beyond the museum the mummies of Guanajuato have entered the pop culture psyche of Mexico. The first person to write about the mummies, however, may have been the American author Ray Bradbury. Known for his science fiction writing, Bradbury published a book of short stories in 1947 written in the horror genre called The October Country. In that book is a story called “The Next in Line” about an American tourist couple visiting Guanajuato for Day of the Dead. The wife dies in the story and this very brief piece examines themes like the fear of death and the need to belong. Author Bradbury wrote the story to get the whole experience of the mummy museum out of his head, to release the demons that had haunted him after a brief visit to the attraction with his own wife. Below is a quote of a description of the mummies from Bradbury’s story:

“Jaws down, tongues out like jeering children, eyes pale brown-irised in upclenched sockets. Hairs, waxed and prickled by sunlight, each sharps as quills embedded on the lips, the cheeks, the eyelids, the brows. Little beards on chins and bosoms and loins. Flesh like drumheads and manuscripts and crisp bread dough. The women, huge ill-shaped tallow things, death-melted. The insane hair of them, like nests made and remade…”

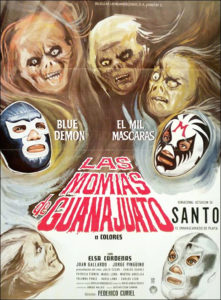

Mummy movies with an Egyptian twist were popular in the United States in the 1930s and 1940s. At the same time, during the “Golden Age” of Mexican cinema an Aztec mummy would pop up here and there but never the mummies of Guanajuato. The main movie that put the mummies we speak of on the map was the 1971 film called “Santo Contra las Momias de Guanajuato.” Translated into English, this means “Santo Against the Mummies of Guanajuato.” This was followed up a year later with a sequel, “The Theft of the Mummies of Guanajuato.” The star of the films, Santo, was a famous Mexican wrestler, of Lucha Libre fame, and in the 1960s and 1970s he and other wrestlers such as El Mil Máscaras and Blue Demon would battle monsters and evil superheroes, among them Dracula, the Spiders from Hell, the Vampire Women, the Wolf Man, and of course, the Mummies of Guanajuato. In the first film about the mummies, one of the mummies comes back to life to seek revenge against Santo because when he was alive he was a wrestler, too, and battled one of Santo’s ancestors. The now-reanimated former wrestler is the 7-foot-tall Satán and he gets the help of several of the other mummies from the museum to go after Santo, killing and terrorizing the townsfolk along the way. The mummies can’t be killed with bullets. Santo, however, knows how to kill them because of his family history.

Mummy movies with an Egyptian twist were popular in the United States in the 1930s and 1940s. At the same time, during the “Golden Age” of Mexican cinema an Aztec mummy would pop up here and there but never the mummies of Guanajuato. The main movie that put the mummies we speak of on the map was the 1971 film called “Santo Contra las Momias de Guanajuato.” Translated into English, this means “Santo Against the Mummies of Guanajuato.” This was followed up a year later with a sequel, “The Theft of the Mummies of Guanajuato.” The star of the films, Santo, was a famous Mexican wrestler, of Lucha Libre fame, and in the 1960s and 1970s he and other wrestlers such as El Mil Máscaras and Blue Demon would battle monsters and evil superheroes, among them Dracula, the Spiders from Hell, the Vampire Women, the Wolf Man, and of course, the Mummies of Guanajuato. In the first film about the mummies, one of the mummies comes back to life to seek revenge against Santo because when he was alive he was a wrestler, too, and battled one of Santo’s ancestors. The now-reanimated former wrestler is the 7-foot-tall Satán and he gets the help of several of the other mummies from the museum to go after Santo, killing and terrorizing the townsfolk along the way. The mummies can’t be killed with bullets. Santo, however, knows how to kill them because of his family history.

Since the early ‘70s there have been a few low-budget knock-offs of the wrestler movies but nothing really has been made about the Mummies of Guanajuato in the pop culture arena until fairly recently, possibly as a reaction to the popularity of zombie movies in the United States. In 2014 an animated film came out of Mexico called “La Leyenda de las Momias de Guanajuato,” starring children as the protagonists. As with the wrestler movies, in this movie the mummies come alive and cause havoc amongst the Guanajuato citizenry. A few years ago a children’s book came out on this side of the border written by James Luna called “A Mummy in Her Backpack” about a girl named Flor and how after visiting Mexico finds that a small mummy from the Guanajuato museum hitched a ride in her backpack and now she must deal with it in the United States. As zombie movies continue to be popular in the United States we can be sure that the Mexicans will answer to this with their own home-grown equivalent. The last of the fictionalization of the mummies of Guanajuato has yet to be seen.

Since the early ‘70s there have been a few low-budget knock-offs of the wrestler movies but nothing really has been made about the Mummies of Guanajuato in the pop culture arena until fairly recently, possibly as a reaction to the popularity of zombie movies in the United States. In 2014 an animated film came out of Mexico called “La Leyenda de las Momias de Guanajuato,” starring children as the protagonists. As with the wrestler movies, in this movie the mummies come alive and cause havoc amongst the Guanajuato citizenry. A few years ago a children’s book came out on this side of the border written by James Luna called “A Mummy in Her Backpack” about a girl named Flor and how after visiting Mexico finds that a small mummy from the Guanajuato museum hitched a ride in her backpack and now she must deal with it in the United States. As zombie movies continue to be popular in the United States we can be sure that the Mexicans will answer to this with their own home-grown equivalent. The last of the fictionalization of the mummies of Guanajuato has yet to be seen.

REFERENCES (Not a formal bibliography):

The official web site of the Mummy Museum of Guanajuato: http://www.momiasdeguanajuato.gob.mx/english/index.html

The Texas State University Guanajuato Mummy Project: http://www.txstate.edu/news/news_releases/news_archive/2007/08/mummies083007.html

The October Country by Ray Bradbury

Link to the 1971 wrestler-themed movie, “Santo Contra Las Momias de Guanajuato” (In Spanish, for as long as the link will last): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vw5wZ9h30k4