Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

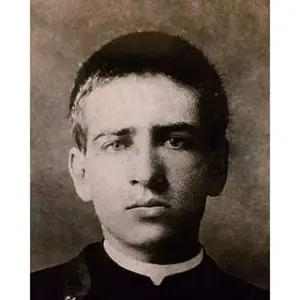

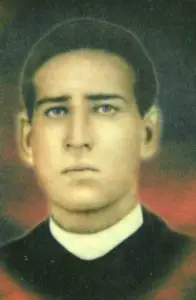

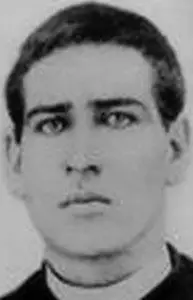

Santo Toribio Romo – in Latin, Saint Thuribius – was a humble parish priest born in the Mexican state of Jalisco who has become one of the most venerated saints among the Mexicans. Unlike the Santa Muerte and Jesus Malverde, profiled here on Mexico Unexplained in episodes 9 and 7 respectively, Saint Toribio was a real living person who is formally recognized by the Catholic Church and was canonized by then Pope John Paul the Second in the year 2000.

Santo Toribio Romo – in Latin, Saint Thuribius – was a humble parish priest born in the Mexican state of Jalisco who has become one of the most venerated saints among the Mexicans. Unlike the Santa Muerte and Jesus Malverde, profiled here on Mexico Unexplained in episodes 9 and 7 respectively, Saint Toribio was a real living person who is formally recognized by the Catholic Church and was canonized by then Pope John Paul the Second in the year 2000.

Our story begins in the deserts of the American Southwest in the early 1980s. We find a young man from Zacatecas stranded in the desert somewhere north of the US Mexico border near Mexicali. His name is Jesús Buendía Gaytán. A few days of wandering, lost, exhausted from the heat and with no water, a truck approached Jesús when he thought all hope was lost. Out of the truck emerged a blue-eyed Mexican man in his 20s, who offered Jesús water and food and told him of a place to get work. When Jesús asked the stranger what he wanted for payment, the young, man told him that when he had enough money to return to Mexico, to look for him at a small church in the town of Santa Ana de Guadalupe in Jalisco where he served as a parish priest. Years later, Jesús did just that and was amazed to see the portrait of his desert savior hanging over the altar of town’s church. The only problem here was that the Good Samaritan who had helped him had died some 50 years before that desert encounter. There are many other stories of a man who fits Toribio Romo’s description helping migrants in the desert. Sometimes he appears to offer tangible things like water or money. Sometimes he appears to console the travelers or encourage them to keep going. Sometimes he has even been known to encourage people to return to Mexico. Sometimes he appears fully frocked as a priest and sometimes wearing the simple clothes of a Mexican cowboy. In all cases, he is there to help with the journey.

No one knows how Toribio Romo became the de facto patron saint of border crossers or those undertaking perilous journeys. While the Catholic Church recognizes him as a saint, they do not recognize him as the patron saint of migrants, a role he has assumed seemingly spontaneously. The Vatican’s official saint for migrants, ironically, is the first American citizen to become a saint, Mother Frances Cabrini, an Italian nun who helped Italian immigrants in the US in the late 19th Century. As Mexicans have a hard time identifying with Mother Cabrini, Santo Toribio has filled the void and has been growing in popularity as the patron saint of Mexican migrants ever since his canonization.

No one knows how Toribio Romo became the de facto patron saint of border crossers or those undertaking perilous journeys. While the Catholic Church recognizes him as a saint, they do not recognize him as the patron saint of migrants, a role he has assumed seemingly spontaneously. The Vatican’s official saint for migrants, ironically, is the first American citizen to become a saint, Mother Frances Cabrini, an Italian nun who helped Italian immigrants in the US in the late 19th Century. As Mexicans have a hard time identifying with Mother Cabrini, Santo Toribio has filled the void and has been growing in popularity as the patron saint of Mexican migrants ever since his canonization.

So who was Toribio Romo, the man? He was born in the year 1900 in the small farming town of Santa Ana de Guadalupe in Jalisco a little ways off the main road leading from Guadalajara to San Juan de los Lagos. He was from a very poor family, but early on young Toribio stood out from the other children for his intelligent and contemplative nature. From an early age he wanted to go to seminary and become a priest but his family hesitated in sending him away. In 1912 Romo entered the Auxiliary Seminary about 25 miles away in San Juan de los Lagos. Ten years later he became a priest, one of the youngest to be ordained in Mexico which  required special permission from the Vatican.

required special permission from the Vatican.

Toribio Romo has been described as a deep thinker and scholar, constantly challenged by matters of faith and always examining his conscience. He was known for having a fine mind and gentle nature. He also loved writing. In an ironic twist, in 1920, while still in seminary, Toribio Romo published a play called “Let’s Go North!” a comedy about the perils of crossing the border to find work in the United States and what would happen to a man after spending too much time on the other side of the border. Like many Catholic priests of the time, Romo discouraged people from leaving their small towns to seek work in the United States. His one-act play consists of two characters, the Americanized Mexican Don Rogaciano who returns to his town with money and fancy clothes, and an attitude of superiority and worldliness, and Sancho, a smart-mouthed local who never left Mexico. Don Rogaciano tries to impress the townsfolk with his command of English and his city ways, and denounces village priests as “money-grubbing retrograde obscurantists.” In the end Sancho gets the best of Rogaciano by beating him with a cane, but Toribio Romo’s main message of the play can be found in some of the final words of the Sancho character when he says this: “Take a good look at what becomes of the Mexican who goes north. He ends up a man without religion, without a country or home… a coward, a feminized man who is incapable of feeling shame for having abandoned his responsibilities to his family. Despite this, the roads are packed with Mexicans headed toward the United States in search of bitter bread. Everywhere you hear the rallying cry: ‘Let’s go north!’”

To understand the saint’s life and death, we have to examine the times in which he was alive. Toribio Romo lived during a dark and often unexamined period in Mexican history. As a young priest Father Romo found himself in the middle of the Cristero War also known as the Cristero Rebellion or La Cristiada, a brutal internal conflict that lasted between 1926 and 1929 and pitted rural Catholic lay people and clergymen against the forces of the anti-Catholic, anti-clerical central government in Mexico City headed by President Plutarco Calles. Calles sought to enforce the anti-clerical articles of the new Constitution of 1917 produced by the Mexican Revolution and enacted legislation to reduce the power of the Church. This so-called Calles Law was seen as a continuation of the long struggle of Church versus State that dated back to La Reforma of the mid-19th Century. Under this law restrictions were placed on the Catholic clergy and the power of the Church was further limited. Popular religious celebrations were suppressed in local communities along with the number of priests allowed to serve in Mexico as a whole. A few uprisings happened in 1926 and full-scale violence ensued by 1927, most notably in the countryside of the states of Zacatecas, Jalisco and Michoacan. By 1927 all priests were prohibited from celebrating the mass and ordered confined to their residences or to relocate to urban areas. Most clergy did not take part in violence, although many, like Father Toribio, defied the authorities and continued performing Catholic rites. The Church hierarchy in Mexico tacitly supported the grassroots rebellion and the authorities in Rome condemned the Mexican government. Curiously, two groups from the United States involved themselves in this war. The Knights of Columbus, a service arm of the Catholic Church, donated money to the Cristero movement. When the first donation of the Knights was announced, another group of Americans calling themselves knights – the Ku Klux Klan – offered President Calles $10,000 to fight against the Cristeros. By 1928, Dwight Whitney Morrow, the US Ambassador to Mexico at the time became involved and eventually helped broker a truce between government forces and the Cristeros. In the end, approximately a quarter million people died in the fighting, and Toribio Romo was among them. On Friday, February 24, 1928, just a year before the end of the war, soldiers broke into the bedroom of Father Romo who had been taking an afternoon nap. A few tense moments and two bullets later, the humble priest, who never took up arms or antagonized any uprising against the authorities, was dead. He was 27 years old.

To understand the saint’s life and death, we have to examine the times in which he was alive. Toribio Romo lived during a dark and often unexamined period in Mexican history. As a young priest Father Romo found himself in the middle of the Cristero War also known as the Cristero Rebellion or La Cristiada, a brutal internal conflict that lasted between 1926 and 1929 and pitted rural Catholic lay people and clergymen against the forces of the anti-Catholic, anti-clerical central government in Mexico City headed by President Plutarco Calles. Calles sought to enforce the anti-clerical articles of the new Constitution of 1917 produced by the Mexican Revolution and enacted legislation to reduce the power of the Church. This so-called Calles Law was seen as a continuation of the long struggle of Church versus State that dated back to La Reforma of the mid-19th Century. Under this law restrictions were placed on the Catholic clergy and the power of the Church was further limited. Popular religious celebrations were suppressed in local communities along with the number of priests allowed to serve in Mexico as a whole. A few uprisings happened in 1926 and full-scale violence ensued by 1927, most notably in the countryside of the states of Zacatecas, Jalisco and Michoacan. By 1927 all priests were prohibited from celebrating the mass and ordered confined to their residences or to relocate to urban areas. Most clergy did not take part in violence, although many, like Father Toribio, defied the authorities and continued performing Catholic rites. The Church hierarchy in Mexico tacitly supported the grassroots rebellion and the authorities in Rome condemned the Mexican government. Curiously, two groups from the United States involved themselves in this war. The Knights of Columbus, a service arm of the Catholic Church, donated money to the Cristero movement. When the first donation of the Knights was announced, another group of Americans calling themselves knights – the Ku Klux Klan – offered President Calles $10,000 to fight against the Cristeros. By 1928, Dwight Whitney Morrow, the US Ambassador to Mexico at the time became involved and eventually helped broker a truce between government forces and the Cristeros. In the end, approximately a quarter million people died in the fighting, and Toribio Romo was among them. On Friday, February 24, 1928, just a year before the end of the war, soldiers broke into the bedroom of Father Romo who had been taking an afternoon nap. A few tense moments and two bullets later, the humble priest, who never took up arms or antagonized any uprising against the authorities, was dead. He was 27 years old.

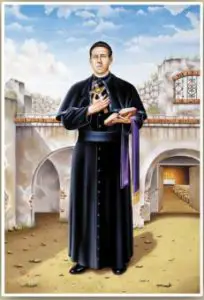

Father Toribio Romo later became one of the 25 Mexican Martyrs of the Cristero War honored by the Catholic Church. He was later beatified and then canonized. Since his canonization in the year 2000 great interest has developed in the saint and thousands of people flock to the tiny town of Santa Ana de Guadalupe to visit his shrine and to see where he spent his youth. As with many shrines in Mexico, supporting businesses have grown up alongside the attraction to serve the multitudes of pilgrims who come each year. Where there were no restaurants in Santa Ana, there are now 3, along with an ice cream shop and many other stores to cater to tourists. It was said by one of the locals that Santo Toribio managed to accomplish in death what he couldn’t in life: the local population is more permanent now. The people of Santa Ana are not forced to go to the United States looking for work, rather, they now live off the steady income that the tourist trade provides.

Father Toribio Romo later became one of the 25 Mexican Martyrs of the Cristero War honored by the Catholic Church. He was later beatified and then canonized. Since his canonization in the year 2000 great interest has developed in the saint and thousands of people flock to the tiny town of Santa Ana de Guadalupe to visit his shrine and to see where he spent his youth. As with many shrines in Mexico, supporting businesses have grown up alongside the attraction to serve the multitudes of pilgrims who come each year. Where there were no restaurants in Santa Ana, there are now 3, along with an ice cream shop and many other stores to cater to tourists. It was said by one of the locals that Santo Toribio managed to accomplish in death what he couldn’t in life: the local population is more permanent now. The people of Santa Ana are not forced to go to the United States looking for work, rather, they now live off the steady income that the tourist trade provides.

The official saint statue of Toribio Romo went on tour to various Mexican-American parishes in California in 2013. The statue includes a relic of the saint, a piece of Romo’s ankle bone, encased in glass affixed to the torso of the statue. People flocked to Indio, Hawthorn, Reseda and other cities to catch a glimpse of the saint, to thank him or to ask for a miracle. The traveling saint proved more popular than the Church could have imagined with thousands of pilgrims showing up at events.

Returning to the migrants in the desert, alone, beaten by the sun, dehydrated, running from the authorities and threatened by rattlesnakes. Who comes to them in the middle of the wasteland when all hope is nearly lost? Is this angelic coyote a mere hallucination or a product of wishful thinking, or is this mysterious blue-eyed man sent by the divine to help those unfortunate people along to live a life on earth that for him was cut short? You decide.

REFERENCES

No book references were used in this episode, only online research. A recommended movie to see, in Spanish only, about Santo Toribio Romo is “Santo Toribio Romo: Del Sueño a la Gloria.”

7 thoughts on “Saint Toribio Romo: Mexican Martyr and Angel to Migrants”

Peace in Christ,

I’m serafin parcon from the Philippines. I humbly ask a favor if you have extra 3rd class relic card of

Saint Toribio Romo, May i have one? May God bless you.

In Christ,

serafin parcon

I’m sorry Serafin, I have none.

Serafin parcon.. do you have facebook?

Paint your own!

Suggested in love.

Hello I have something A necklace of Toribio Romo it was made in the year 2000 so when he was canonized I’m 14 about to be 15 but yeah

Roberto: Where are you getting the quotes from Romo’s play, Let’s Go North? I’m trying to get a copy of the play.

Hi David, I did this show a long time ago. If I remember correctly, I found it online in Spanish by following links of links. In Spanish the play is called “Vamos al Norte.” I am sure you can find it, but not in English. Let me know if you have any other questions.