Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

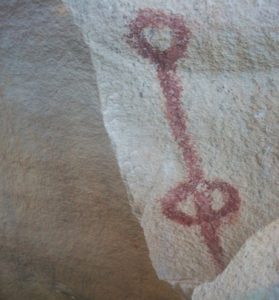

The date was May 21, 2013. Archaeologist Martha García Sánchez was giving a presentation at the Second Colloquium on Historical Archeology at Mexico’s National History Museum in Chapultepec Castle located in the heart of Mexico City. García Sánchez, who had recently graduated from the Autonomous University of Zacatecas, was supported at the podium by Gustavo Ramírez a fellow archaeologist from the Tamaulipas office of the Mexican National Institute of Anthropology and History. The two were presenting finds from the Sierra de San Carlos in the northeastern Mexican state of Tamaulipas, which were part of García Sánchez’ doctoral dissertation. Sometime in the early 2000s a small group of hikers entered a remote ravine in the mountains. The hikers discovered thousands of rock paintings throughout a series of small canyons and caves. Human figures, animals and intricate scenes were painted on the walls in yellow, red, white and black, with some of the paintings looking as if they were made just decades ago. To anyone’s knowledge, no one in modern times had ever seen these magnificent drawings and paintings, not even the locals, who had no cause to go into that remote part of the Sierras. By the year 2006 the National Institute of Anthropology and History out of Mexico City became interested in this previously unknown rock art site. They coordinated with their Tamaulipas field office in Ciudad Victoria, the state capital, about 60 miles south of the site which is in the municipio or Municipality of Burgos. In Mexico, a municipio, or municipality, is much like a county in the English-speaking world. The Institute sent teams of researchers to the municipio deep into the San Carlos Mountains and spent two years photographing, drawing and otherwise documenting the 4,926 images painted and etched onto the walls of caves and small canyons. Although the huge gallery of prehistoric art was discovered by ordinary citizen hikers, the area is now strictly off limits to the public. When an important archaeological or other historical find is made within Mexico’s borders, the National Institute of Anthropology and History wastes no time in putting a lid on the discovery.

The date was May 21, 2013. Archaeologist Martha García Sánchez was giving a presentation at the Second Colloquium on Historical Archeology at Mexico’s National History Museum in Chapultepec Castle located in the heart of Mexico City. García Sánchez, who had recently graduated from the Autonomous University of Zacatecas, was supported at the podium by Gustavo Ramírez a fellow archaeologist from the Tamaulipas office of the Mexican National Institute of Anthropology and History. The two were presenting finds from the Sierra de San Carlos in the northeastern Mexican state of Tamaulipas, which were part of García Sánchez’ doctoral dissertation. Sometime in the early 2000s a small group of hikers entered a remote ravine in the mountains. The hikers discovered thousands of rock paintings throughout a series of small canyons and caves. Human figures, animals and intricate scenes were painted on the walls in yellow, red, white and black, with some of the paintings looking as if they were made just decades ago. To anyone’s knowledge, no one in modern times had ever seen these magnificent drawings and paintings, not even the locals, who had no cause to go into that remote part of the Sierras. By the year 2006 the National Institute of Anthropology and History out of Mexico City became interested in this previously unknown rock art site. They coordinated with their Tamaulipas field office in Ciudad Victoria, the state capital, about 60 miles south of the site which is in the municipio or Municipality of Burgos. In Mexico, a municipio, or municipality, is much like a county in the English-speaking world. The Institute sent teams of researchers to the municipio deep into the San Carlos Mountains and spent two years photographing, drawing and otherwise documenting the 4,926 images painted and etched onto the walls of caves and small canyons. Although the huge gallery of prehistoric art was discovered by ordinary citizen hikers, the area is now strictly off limits to the public. When an important archaeological or other historical find is made within Mexico’s borders, the National Institute of Anthropology and History wastes no time in putting a lid on the discovery.

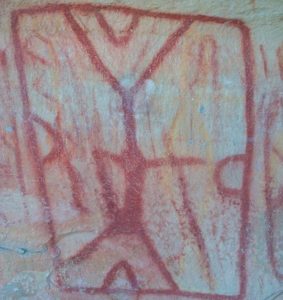

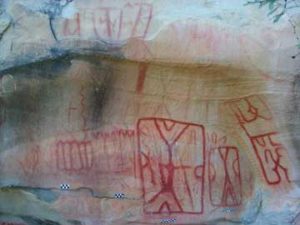

In her presentation at Chapultepec Castle, archaeologist Martha García Sánchez thanked Mexico’s National Fund for Culture and the Arts for their support of this important ongoing research, and started a slideshow depicting the thousands of images she had been researching along with Gustavo Ramírez and the Tamaulipas team. García Sánchez commented that eleven sites in the Sierra de San Carlos have been visited, such as Cueva de los Caballos, within the Cañon El Bronce; La Noria and Las Colmenas, within the Cañon La Noria; and El Carrizo in the Cañada de Las Pozas, among others. The images, she added, suggest that the activities of the nomadic people who created them focused on hunting, fishing and gathering. By looking at the styles, materials used and wear to the paintings and drawings, the researchers theorized that three distinct groups may have been responsible for the art. The archaeologists classified the images into four categories: anthropomorphic, zoomorphic, astronomical and abstract. Some images mix categories to create elaborate scenes that seem to tell complex stories. García Sánchez said this to a captivated audience about the significance of this find in northeastern Mexico:

“Their importance lies in the fact that based on them we have been able to document the presence of pre-Hispanic groups in Burgos (Municipality), where it was previously said that there was nothing. In the Cueva de los Caballos we recorded more than 1,550 images; but we still need to analyze the cultural component of the paintings because a mitote is represented there. In the Cueva del Indio we find representations of an atlatl, which had not been found in any other rock art of Tamaulipas, either. ”

“Their importance lies in the fact that based on them we have been able to document the presence of pre-Hispanic groups in Burgos (Municipality), where it was previously said that there was nothing. In the Cueva de los Caballos we recorded more than 1,550 images; but we still need to analyze the cultural component of the paintings because a mitote is represented there. In the Cueva del Indio we find representations of an atlatl, which had not been found in any other rock art of Tamaulipas, either. ”

A mitote is a circular dance of ancient Mexico performed by the Aztecs and many other civilizations before them. Participants join hands in a circle and the circle moves in a clockwise or counterclockwise motion around a central focal point. In the modern arts and crafts of Mexico, this is represented in the common so-called “circle of friends” clay tabletop sculpture popular in the late 1990s and early 2000s and found in many American homes with Mexican décor. Archaeologists believe the mitote dance originated some 2,500 years ago in what is now western Mexico in the modern-day state of Jalisco and is associated with the Chupícuaro Culture. The scene of a mitote “Circle of Friends” dance is out of place and unique in this region of Mexico. García Sánchez also mentioned the depiction of an atlatl at the site, which is a prehistoric throwing spear. These weapons were used by many different groups throughout prehistoric Mexico all the way up through the Aztec era and into the time of Spanish colonization. The northern tribes collectively known as Chicimeca were adeptly skilled in the use of the atlatl in hunting and in warfare. Nowhere else in Tamaulipas, though, is there an atlatl depicted in ancient rock art.

It was difficult for the archaeological team researching the Burgos rock art site to pin down just who created these images. These are paintings and drawings, not like the chipped out petroglyphs found at various sites throughout northern Mexico. The style of the art looks remarkably like the rock art in Baja California some 700 miles away, as the crow flies. The images and colors used seem very similar. For more information about the rock art of Baja, please see Mexico Unexplained episode number 116: https://mexicounexplained.com//mysterious-rock-paintings-baja/ The researchers noted the depiction of teepees in the art, which indicated a mobile, nomadic population. The fact that a dance that originated in western Mexico – the mitote – is illustrated here may indicate some connection to the western part of the country, but it is hard to determine what kind of connection. Did someone from the Burgos area visit western Mexico in ancient times and witness this dance on his travels? Did settlers from central or western Mexico make it through hostile Chichimeca territory and settle in the vicinity? There were no artifacts found in any of the caves or canyons where this art graces the walls, no remains of firepits or other organic material for dating. It’s almost as if the site was used as either a pilgrimage place or it was a place where people left their marks in a detailed way when they were passing through. No one lived there, most likely. In addition, the hematite used in the red paint found overwhelmingly throughout the art, is not sourced locally. The closest place where the hematite can be obtained is well over 100 miles away in Querétero, indicating trade or some sort of travel back and forth. Martha García Sánchez and Gustavo Ramírez consulted archival sources to try to figure out what group or groups were responsible for this magnificent art in this remote area. They went to the local archives in Burgos, both church and municipal. They then went to the state libraries and archives of Nuevo Leon and Tamaulipas. They finished their search with colonial archives in Mexico City. They came up with practically no information about the mountain people of Tamaulipas who lived there before the conquest. There may have been some Aztec incursion in the area, but most of this northern territory was off limits as it was controlled by various diverse groups that the Aztecs painted with a broad brush and just called “Chichimeca.” For more information about the Chichimecs, please see Mexico Unexplained episode number 142: https://mexicounexplained.com//chichimeca-warriors-of-the-north/ Early Spanish and French explorers arrived in the area in the 1500s and made little note of the people they found there. Only 200 years after the Spanish Conquest of the Aztecs did Europeans first settle in the area, first with missions. García Sánchez noted in her presentation that at the time of the evangelization of the Burgos area, many indigenous people, “fled to the Sierra de San Carlos where they had water, plants and animals to feed. On the other hand, the Spaniards did not go into the mountains and its ravines.” The fact that natives escaped to the mountains during the mid-1700s does not indicate that the art was created at that time or by those who fled to the remote wilderness of the sierras.

It was difficult for the archaeological team researching the Burgos rock art site to pin down just who created these images. These are paintings and drawings, not like the chipped out petroglyphs found at various sites throughout northern Mexico. The style of the art looks remarkably like the rock art in Baja California some 700 miles away, as the crow flies. The images and colors used seem very similar. For more information about the rock art of Baja, please see Mexico Unexplained episode number 116: https://mexicounexplained.com//mysterious-rock-paintings-baja/ The researchers noted the depiction of teepees in the art, which indicated a mobile, nomadic population. The fact that a dance that originated in western Mexico – the mitote – is illustrated here may indicate some connection to the western part of the country, but it is hard to determine what kind of connection. Did someone from the Burgos area visit western Mexico in ancient times and witness this dance on his travels? Did settlers from central or western Mexico make it through hostile Chichimeca territory and settle in the vicinity? There were no artifacts found in any of the caves or canyons where this art graces the walls, no remains of firepits or other organic material for dating. It’s almost as if the site was used as either a pilgrimage place or it was a place where people left their marks in a detailed way when they were passing through. No one lived there, most likely. In addition, the hematite used in the red paint found overwhelmingly throughout the art, is not sourced locally. The closest place where the hematite can be obtained is well over 100 miles away in Querétero, indicating trade or some sort of travel back and forth. Martha García Sánchez and Gustavo Ramírez consulted archival sources to try to figure out what group or groups were responsible for this magnificent art in this remote area. They went to the local archives in Burgos, both church and municipal. They then went to the state libraries and archives of Nuevo Leon and Tamaulipas. They finished their search with colonial archives in Mexico City. They came up with practically no information about the mountain people of Tamaulipas who lived there before the conquest. There may have been some Aztec incursion in the area, but most of this northern territory was off limits as it was controlled by various diverse groups that the Aztecs painted with a broad brush and just called “Chichimeca.” For more information about the Chichimecs, please see Mexico Unexplained episode number 142: https://mexicounexplained.com//chichimeca-warriors-of-the-north/ Early Spanish and French explorers arrived in the area in the 1500s and made little note of the people they found there. Only 200 years after the Spanish Conquest of the Aztecs did Europeans first settle in the area, first with missions. García Sánchez noted in her presentation that at the time of the evangelization of the Burgos area, many indigenous people, “fled to the Sierra de San Carlos where they had water, plants and animals to feed. On the other hand, the Spaniards did not go into the mountains and its ravines.” The fact that natives escaped to the mountains during the mid-1700s does not indicate that the art was created at that time or by those who fled to the remote wilderness of the sierras.

An independent research group may have come up with the answers as to when these paintings and drawings were made, but they have not yet identified the “who.” Two years after the initial presentation at the Second Colloquium on Historical Archaeology in Mexico City, Andis Kaulins posted an article on the Burgos cave art in his Ancient World blog. It was the 14th post in a series titled “The Great Mound, Petroglyph and Painted Rock Art Journey of Native America.” Kaulins examined a tableau from the Cueva del Indio at Burgos and read it as an astronomical chart. Kaulins says:

“As seen there, some familiar star clusters are clearly marked, as is the Milky Way.

“As seen there, some familiar star clusters are clearly marked, as is the Milky Way.

The hour-glass figure of Orion is unmistakable, and the rest follow logically after that. Cancer, Gemini, and Auriga are clearly marked above the Milky Way, Perseus in turn is marked in the Milky Way, and Canis Major, Orion and Taurus (the latter found in an unusual representation as two halves) together with the Hyades are marked below the Milky Way.

The locational mesh of star clusters and Milky Way (properly placed above, in or below that Milky Way) serves as very strong probative evidence for the correctness of our identification of the prominent star groups.

The “underworld” of the ocean below the Milky Way then shows Canis Major (with Sirius), Puppis (as a squid?), Carina as an electric (?) eel (with “shock” symbols ?, and with the major star Canopus as the eel’s eye), and Columba as a turtle. Stars between Orion and Canis Major are seen as a fence.”

From the positioning of the stars on this Cueva del Indio panel, Kaulins concluded that the painting was made in either 2,500 BC or 5,000 BC, but for some reason is more inclined to believe that the 2,500 BC date is most likely the correct one. Art of a similar style in northern Mexico found in Baja referenced earlier has been dated to 7,500 BC, so an earlier date for Burgos may not be out of the question.

Something else very curious in the region bears mentioning here. South of the town of Burgos and visible from the Sierra de San Carlos is the Cerro de Burgos which stands alone a few hundred feet above the surrounding area. From faraway it looks like a pyramid because of its perfect triangular outline. The locals brag that no matter from what direction one looks at the gigantic hill, it looks the same. It is perfectly round and perfectly proportioned. Is this a massive artificial mound, indicating an older civilization present in the area where there was once no thought of one? If so, is the Cerro de Burgos somehow connected with the rock art?

Something else very curious in the region bears mentioning here. South of the town of Burgos and visible from the Sierra de San Carlos is the Cerro de Burgos which stands alone a few hundred feet above the surrounding area. From faraway it looks like a pyramid because of its perfect triangular outline. The locals brag that no matter from what direction one looks at the gigantic hill, it looks the same. It is perfectly round and perfectly proportioned. Is this a massive artificial mound, indicating an older civilization present in the area where there was once no thought of one? If so, is the Cerro de Burgos somehow connected with the rock art?

Archaeological work at the caves and the surrounding areas of western Tamaulipas has been hindered in recent years due to drug cartel activity in the region. The National Institute of Anthropology and History out of Mexico City claims that the area is too dangerous to open it up to the public for tourism. The cave art of Burgos and the possible other archaeological anomalies in the surrounding area will have to wait for some future researchers to unravel their many mysteries.

REFERENCES

Ancient World Blog by Andis Kaulins

Web site of the National Museum of Anthropology and History – INAH (in Spanish