Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

The Texan Santa Fe Expedition of 1841 stands as one of the most audacious yet disastrous episodes in the short-lived history of the Republic of Texas. Launched under the ambitious presidency of Mirabeau B. Lamar, the venture aimed to seize control of lucrative trade routes and assert territorial claims over eastern New Mexico, then a province of Mexico. What began as a blend of commercial optimism and military bravado unraveled into a tale of hardship, betrayal, and captivity, ultimately hastening Texas’s annexation to the United States. This ill-fated journey not only exposed the fragility of the young republic but also intensified border tensions that would contribute to the Mexican War. In this episode of Mexico Unexplained, we will explore the background, the underlying land dispute, the expedition’s execution, and its far-reaching aftermath.

The Texan Santa Fe Expedition of 1841 stands as one of the most audacious yet disastrous episodes in the short-lived history of the Republic of Texas. Launched under the ambitious presidency of Mirabeau B. Lamar, the venture aimed to seize control of lucrative trade routes and assert territorial claims over eastern New Mexico, then a province of Mexico. What began as a blend of commercial optimism and military bravado unraveled into a tale of hardship, betrayal, and captivity, ultimately hastening Texas’s annexation to the United States. This ill-fated journey not only exposed the fragility of the young republic but also intensified border tensions that would contribute to the Mexican War. In this episode of Mexico Unexplained, we will explore the background, the underlying land dispute, the expedition’s execution, and its far-reaching aftermath.

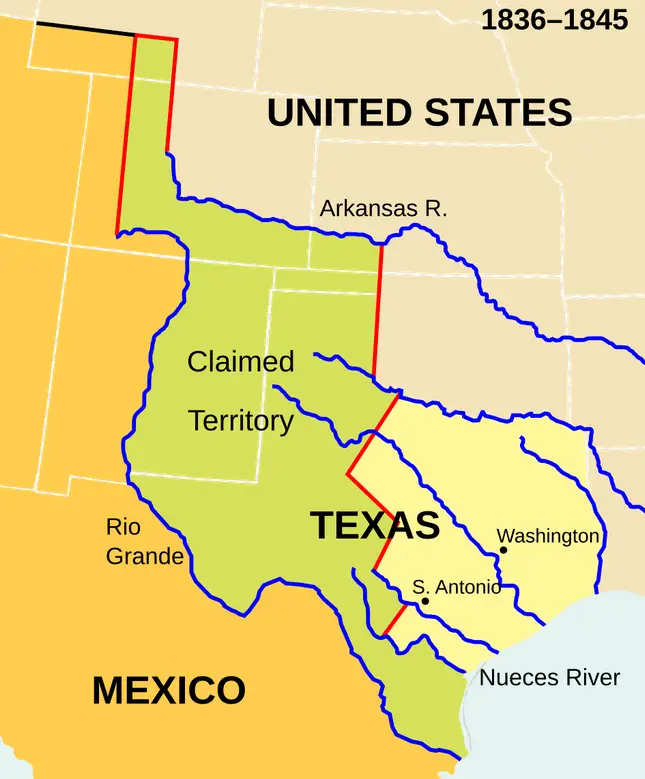

The roots of the Texan Santa Fe Expedition trace back to the turbulent birth of the Republic of Texas. In 1836, Texas declared independence from Mexico following the Texas Revolution, a conflict sparked by cultural clashes, economic grievances, and the centralization of power under Mexican President Antonio López de Santa Anna. Key battles, such as the Alamo and San Jacinto, culminated in Santa Anna’s capture and the signing of the Treaties of Velasco. These agreements, signed on May 14, 1836, recognized Texas’s independence and set its southern boundary at the Rio Grande, a claim that extended Texas’s territory far beyond what Mexico acknowledged. The Republic of Texas, formally established in 1836, faced immediate challenges: a massive debt from the war, threats from Native American tribes, and ongoing disputes with Mexico, which refused to recognize its independence. Sam Houston, the first president, pursued a policy of diplomacy and sought annexation to the United States to bolster security and economy. However, his successor, Mirabeau B. Lamar, elected in 1838, envisioned a grander future. A poet, journalist, and fervent expansionist from Georgia, Lamar dreamed of transforming Texas into a continental empire stretching to the Pacific Ocean. He relocated the capital to Austin, invested in education by endowing lands for universities, and adopted aggressive policies toward Native Americans, ordering their expulsion from eastern Texas to open lands for settlement. Lamar’s administration inherited an economy in shambles, with depreciating currency and reliance on cotton exports. The Santa Fe Trail, a vital overland  trade route connecting Missouri to Santa Fe, New Mexico, represented untapped potential. Established in the 1820s, the trail funneled millions in goods—textiles, hardware, and luxuries—from the United States to Mexico, with returns in silver, furs, and mules. St. Louis monopolized this trade, but Lamar believed Texas’s ports, like Galveston, could divert it southward, injecting much-needed revenue into the republic. Moreover, controlling Santa Fe would affirm Texas’s western claims and potentially inspire New Mexicans, disillusioned with Mexican governance, to join the republic. In 1840, Lamar dispatched commissioner William G. Dryden to Santa Fe with overtures of alliance, but the response was lukewarm, setting the stage for a more direct approach. Lamar’s ambitions soon clashed with political realities. Houston, now in the Texas Congress, opposed expansionist schemes, viewing them as financially reckless. Despite congressional rejection of funding bills in early 1841, Lamar proceeded unilaterally, framing the expedition as a “commercial” venture to skirt legal hurdles. This decision reflected the republic’s precarious sovereignty: without a standing army – which was disbanded due to costs – it relied on volunteers and merchants. The expedition thus embodied the era’s Manifest Destiny ethos, where Anglo-American expansion was seen as inevitable and righteous, even if it meant encroaching on Mexican and Native lands.

trade route connecting Missouri to Santa Fe, New Mexico, represented untapped potential. Established in the 1820s, the trail funneled millions in goods—textiles, hardware, and luxuries—from the United States to Mexico, with returns in silver, furs, and mules. St. Louis monopolized this trade, but Lamar believed Texas’s ports, like Galveston, could divert it southward, injecting much-needed revenue into the republic. Moreover, controlling Santa Fe would affirm Texas’s western claims and potentially inspire New Mexicans, disillusioned with Mexican governance, to join the republic. In 1840, Lamar dispatched commissioner William G. Dryden to Santa Fe with overtures of alliance, but the response was lukewarm, setting the stage for a more direct approach. Lamar’s ambitions soon clashed with political realities. Houston, now in the Texas Congress, opposed expansionist schemes, viewing them as financially reckless. Despite congressional rejection of funding bills in early 1841, Lamar proceeded unilaterally, framing the expedition as a “commercial” venture to skirt legal hurdles. This decision reflected the republic’s precarious sovereignty: without a standing army – which was disbanded due to costs – it relied on volunteers and merchants. The expedition thus embodied the era’s Manifest Destiny ethos, where Anglo-American expansion was seen as inevitable and righteous, even if it meant encroaching on Mexican and Native lands.

At the heart of the Texan Santa Fe Expedition lay a profound territorial dispute between the Republic of Texas and Mexico. The Treaties of Velasco stipulated that Texas’s boundary followed the Rio Grande from its mouth to its source, then northward along the meridian to the Arkansas River, encompassing Santa Fe and much of eastern New Mexico. This claim originated from an 1836 act of the Texas Congress, which boldly asserted jurisdiction over lands east of the Rio Grande, including parts of present-day New Mexico, Oklahoma, Kansas, Colorado, and even Wyoming. Texans justified this by arguing that Santa Anna’s defeat at San Jacinto legitimized the treaties, and that New Mexico’s residents, burdened by high tariffs and distant rule from Mexico City, would welcome liberation. Mexico, however, vehemently rejected these claims. Santa Anna, upon release, repudiated the treaties as coerced under duress, and the Mexican Congress never ratified them. From Mexico’s perspective, Texas remained a rebellious province, with its legitimate southern boundary at the Nueces River, some 150 miles north of the Rio Grande. The vast region between the Nueces and Rio Grande was disputed, but Santa Fe—founded in 1610 as the capital of New Mexico—was unequivocally Mexican territory. Governor Manuel Armijo, a shrewd and authoritarian figure, governed with an iron fist, suppressing revolts like the 1837 Chimayó Rebellion and maintaining loyalty through patronage and force.

The dispute was exacerbated by cultural and economic factors. New Mexico’s population, primarily Hispanos and Pueblo Indians, had little affinity for Anglo-Texans. Trade with the United States via the Santa Fe Trail had enriched merchants, but political allegiance remained with Mexico. Lamar’s rhetoric of “extending the blessings of liberty” masked economic imperialism: Texas sought to monopolize the trail’s profits, estimated at four million dollars annually in the late 1830s. If successful, the expedition could redirect commerce through Texas ports, bypassing St. Louis and invigorating the republic’s economy. Geographically, the claims were ambitious but impractical. The area between settled Texas and Santa Fe was a forbidding wilderness: prairies, canyons, and the Llano Estacado (Staked Plains), inhabited by nomadic tribes like the Comanche and Kiowa, who raided settlements and caravans. Texas lacked accurate maps, underestimating the distance at 500 miles when it was closer to 1,000. This ignorance, combined with Mexico’s military presence in New Mexico – bolstered by warnings from spies – set the stage for failure. The dispute highlighted broader North American tensions: the United States, eyeing westward expansion, watched closely, as Texas’s claims could entangle it in conflict with Mexico.

The dispute was exacerbated by cultural and economic factors. New Mexico’s population, primarily Hispanos and Pueblo Indians, had little affinity for Anglo-Texans. Trade with the United States via the Santa Fe Trail had enriched merchants, but political allegiance remained with Mexico. Lamar’s rhetoric of “extending the blessings of liberty” masked economic imperialism: Texas sought to monopolize the trail’s profits, estimated at four million dollars annually in the late 1830s. If successful, the expedition could redirect commerce through Texas ports, bypassing St. Louis and invigorating the republic’s economy. Geographically, the claims were ambitious but impractical. The area between settled Texas and Santa Fe was a forbidding wilderness: prairies, canyons, and the Llano Estacado (Staked Plains), inhabited by nomadic tribes like the Comanche and Kiowa, who raided settlements and caravans. Texas lacked accurate maps, underestimating the distance at 500 miles when it was closer to 1,000. This ignorance, combined with Mexico’s military presence in New Mexico – bolstered by warnings from spies – set the stage for failure. The dispute highlighted broader North American tensions: the United States, eyeing westward expansion, watched closely, as Texas’s claims could entangle it in conflict with Mexico.

Undeterred by congressional opposition, Lamar orchestrated the expedition in the spring of 1841. He issued a proclamation calling for volunteers, promising military protection for merchants and framing the mission as peaceful trade outreach. The group, dubbed the “Santa Fe Pioneers,” assembled at Kenney’s Fort on Brushy Creek, about 20 miles north of Austin. It comprised 321 men: a military contingent of around 270 under Brigadier General Hugh McLeod, a West Point graduate and Texas veteran; merchants with 21 ox-drawn wagons laden with $200,000 in goods such as textiles, tobacco, and hardware; and civilian commissioners to negotiate with New Mexicans.

Preparation was haphazard. Supplies were insufficient: limited flour, coffee, and salt for months; no accurate maps or experienced guides beyond a Mexican hired early on. A 6-pounder brass cannon and a herd of beef cattle accompanied them, but the wagons were ill-suited for rough terrain. Lamar’s open letter, printed in English and Spanish, invited New Mexicans to join Texas or allow peaceful trade, emphasizing shared “glory of establishing a new and happy and free nation.” The ulterior motive—annexation if welcomed, or force if necessary—was thinly veiled. Departure on June 19, 1841, amid fanfare, marked the start of what Lamar hoped would cement his legacy.

The expedition’s early days were optimistic, crossing fertile prairies and feasting on bison. They forded the Brazos River on July 8 and entered the Cross Timbers by July 21, a dense woodland in present-day Parker County. Here, troubles began: rough terrain slowed wagons, forcing hand-cleared paths. By August, they mistook the Wichita River for the Red River, veering off course into arid  valleys. The Mexican guide deserted, leaving them disoriented. Water scarcity and food shortages intensified. Rations dwindled to a pound of beef daily, including bones; men ate tortoises, snakes, and hides. “I’ve seen the elephant—I’ve had enough!” became a refrain for deserters. On August 13, a prairie fire destroyed wagons and supplies. Kiowa attacks peaked on August 30, killing five scouts in a brutal ambush, with bodies mutilated and one heart excised. Indian harassment continued, stampeding cattle and limiting hunting. McLeod’s illness compounded issues; he enforced drills, sparking mutiny threats. At Quitaque Creek in Motley County, unable to ascend the Caprock Escarpment, McLeod split the force: an advance party of about 100 under Cooke sought settlements, while the main group waited. The vanguard crossed canyons, enduring thirst and starvation. On September 12, they met Mexican traders who promised aid but alerted authorities. The main party, crossing the Llano Estacado, faced similar woes: no water for days, men collapsing from exhaustion. By mid-September, the expedition was fragmented, starved, and lost, far from the anticipated welcome.

valleys. The Mexican guide deserted, leaving them disoriented. Water scarcity and food shortages intensified. Rations dwindled to a pound of beef daily, including bones; men ate tortoises, snakes, and hides. “I’ve seen the elephant—I’ve had enough!” became a refrain for deserters. On August 13, a prairie fire destroyed wagons and supplies. Kiowa attacks peaked on August 30, killing five scouts in a brutal ambush, with bodies mutilated and one heart excised. Indian harassment continued, stampeding cattle and limiting hunting. McLeod’s illness compounded issues; he enforced drills, sparking mutiny threats. At Quitaque Creek in Motley County, unable to ascend the Caprock Escarpment, McLeod split the force: an advance party of about 100 under Cooke sought settlements, while the main group waited. The vanguard crossed canyons, enduring thirst and starvation. On September 12, they met Mexican traders who promised aid but alerted authorities. The main party, crossing the Llano Estacado, faced similar woes: no water for days, men collapsing from exhaustion. By mid-September, the expedition was fragmented, starved, and lost, far from the anticipated welcome.

The advance party’s scouts reached New Mexico on September 17, only to encounter Mexican troops under Captain Damasio Salazar. Two were executed fleeing; Captain Lewis, posing as interpreter, betrayed his comrades, exaggerating Armijo’s forces and swearing on his Masonic oath for safe passage if they disarmed. Cooke surrendered, expecting trade. The main force, arriving at Laguna Colorada near Tucumcari on October 5, yielded to Colonel Juan Andrés Archuleta without resistance, outnumbered and depleted. Armijo, informed by spies, arrived and demanded execution; a council vote spared them by one. Stripped of possessions, the Texans—now prisoners—were bound and marched 2,000 miles south along the Camino Real to Mexico City. Under Salazar, treatment was savage: 30-mile forced marches on blistered feet, minimal rations, beatings, and killings. In the Jornada del Muerto desert, men died of thirst; ears were severed as proof. Women in pueblos offered secret aid. Reaching El Paso on November 4, they rested briefly before continuing to Veracruz’s Perote Prison, arriving in February 1842. About 60 perished from disease, fatigue, or violence; survivors endured harsh confinement, some as forced laborers.

U.S. diplomacy, fueled by outrage over prisoner mistreatment, secured releases starting in April 1842, with the last on June 13. Survivors like journalist George Wilkins Kendall returned to New Orleans, their accounts sparking sympathy. The failure devastated Lamar: the Texas Congress considered impeachment, criticizing his unauthorized actions as reckless. It exposed Texas’s inability to hold western lands, draining resources and morale. Politically, it bolstered Houston’s annexation push; Texas joined the U.S. in 1845, shifting disputes to the federal level. Prisoner tales heightened anti-Mexican sentiment, contributing to the 1846 Mexican War.

U.S. diplomacy, fueled by outrage over prisoner mistreatment, secured releases starting in April 1842, with the last on June 13. Survivors like journalist George Wilkins Kendall returned to New Orleans, their accounts sparking sympathy. The failure devastated Lamar: the Texas Congress considered impeachment, criticizing his unauthorized actions as reckless. It exposed Texas’s inability to hold western lands, draining resources and morale. Politically, it bolstered Houston’s annexation push; Texas joined the U.S. in 1845, shifting disputes to the federal level. Prisoner tales heightened anti-Mexican sentiment, contributing to the 1846 Mexican War.

Post-war, the 1850 Compromise saw Texas cede northwestern claims, including Santa Fe, for $10 million in debt relief, forming New Mexico Territory. The expedition’s legacy endures in literature: Kendall’s 1844 Narrative influenced public opinion; it inspired novels like Larry McMurtry’s Dead Man’s Walk. Historically, it marked the end of Texas’s imperial dreams, paving the way for U.S. expansion. As historian David Lavender quipped, it was “one of the most cockeyed ventures in American history,” a cautionary tale of ambition outpacing reality.

REFERENCES