Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

Driving through the evergreen forests of the highlands of the Mexican state of Michocán the traveler will find on the map a curious place called Villa Escalante. Villa Escalante is the modern-day formal name for a town historically known as Santa Clara del Cobre. If you take the short bus ride from Morelia or Pátzcuaro to this place you will be greeted by the sounds of hammers on copper, the *ting* *ting* *ting* of craftsmen shaping newly forged pieces of red-orange metal into beautiful and functional works of folk art. Famous for their big copper cazos or cauldrons, the town is also known for a wide variety of things made from this ubiquitous metal, from jewelry to candleholders to fancy tableware and other utilitarian items. It seems like the whole town is engaged in some sort of copper craft production. When I first visited Santa Clara del Cobre as a student based in Morelia back in 1989, I was told that other towns in this part of Michoacán – the traditional homeland of the Tarascan Indians – specialized in certain crafts, too: In Paracho it was guitars, in Tzintzuntzan it was a certain type of pottery, and so on. As a curious student, I had more questions as to why certain towns focused on certain crafts and then I stumbled upon the history of Vasco de Quiroga, a man who worked tirelessly well into his 90s to try right the wrongs of the people who came before him. Here is his story.

Driving through the evergreen forests of the highlands of the Mexican state of Michocán the traveler will find on the map a curious place called Villa Escalante. Villa Escalante is the modern-day formal name for a town historically known as Santa Clara del Cobre. If you take the short bus ride from Morelia or Pátzcuaro to this place you will be greeted by the sounds of hammers on copper, the *ting* *ting* *ting* of craftsmen shaping newly forged pieces of red-orange metal into beautiful and functional works of folk art. Famous for their big copper cazos or cauldrons, the town is also known for a wide variety of things made from this ubiquitous metal, from jewelry to candleholders to fancy tableware and other utilitarian items. It seems like the whole town is engaged in some sort of copper craft production. When I first visited Santa Clara del Cobre as a student based in Morelia back in 1989, I was told that other towns in this part of Michoacán – the traditional homeland of the Tarascan Indians – specialized in certain crafts, too: In Paracho it was guitars, in Tzintzuntzan it was a certain type of pottery, and so on. As a curious student, I had more questions as to why certain towns focused on certain crafts and then I stumbled upon the history of Vasco de Quiroga, a man who worked tirelessly well into his 90s to try right the wrongs of the people who came before him. Here is his story.

Vasco de Quiroga hailed from a minor noble family from the Kingdom of Castile, one of the Iberian kingdoms that eventually became the modern nation of Spain. He was born in the province of Avila, in the village of Madrigal de las Altas Torres, the same place where Queen Isabella of Christopher Columbus fame was also born. There is some dispute as to what year Quiroga was born. At the time of his death in 1565 it was noted that he was 95 years old, so that would put his birth year as 1470. However, in 1538, in his own hand, Quiroga wrote that he was 60 years old. That would put his birth year as 1478. In any case, he was born into a society that was rapidly changing. As a teenager or young adult, Quiroga lived through the expulsion of the Muslims from Spain, the discoveries of Christopher Columbus and the formation of the Spanish Empire. Although Quiroga later became a bishop, his primary focus of study as a young man was law and he had no aspirations to become a priest or to serve in any sort of ecclesiastical capacity. Early on, Quiroga distinguished himself as a well-read and brilliant young man. After spending time working in the records office for the legal courts in the town of Badajoz near Spain’s border with Portugal, Quiroga eventually became a judge in southern Spain only a few years after Islamic rule had ended in the area. By the early 1500s Spain had expanded into North Africa, capturing several Arabic towns on the coast. One of these was Oran, located in modern-day Algeria. Vasco de Quiroga served as a judge in Spanish-occupied Oran from 1520 to 1526. By 1528 he found himself back in Spain at the royal court where he moved among powerful and influential people. There he befriended the Cardinal of Toledo and also Juan Bernal Díaz who was a member of the Council of the Indies which oversaw Spain’s overseas possessions. It was through his connections at court during this time that Vasco de Quiroga came to serve the Spanish king in the New World. By this time he was already approaching 60 years old.

Vasco de Quiroga hailed from a minor noble family from the Kingdom of Castile, one of the Iberian kingdoms that eventually became the modern nation of Spain. He was born in the province of Avila, in the village of Madrigal de las Altas Torres, the same place where Queen Isabella of Christopher Columbus fame was also born. There is some dispute as to what year Quiroga was born. At the time of his death in 1565 it was noted that he was 95 years old, so that would put his birth year as 1470. However, in 1538, in his own hand, Quiroga wrote that he was 60 years old. That would put his birth year as 1478. In any case, he was born into a society that was rapidly changing. As a teenager or young adult, Quiroga lived through the expulsion of the Muslims from Spain, the discoveries of Christopher Columbus and the formation of the Spanish Empire. Although Quiroga later became a bishop, his primary focus of study as a young man was law and he had no aspirations to become a priest or to serve in any sort of ecclesiastical capacity. Early on, Quiroga distinguished himself as a well-read and brilliant young man. After spending time working in the records office for the legal courts in the town of Badajoz near Spain’s border with Portugal, Quiroga eventually became a judge in southern Spain only a few years after Islamic rule had ended in the area. By the early 1500s Spain had expanded into North Africa, capturing several Arabic towns on the coast. One of these was Oran, located in modern-day Algeria. Vasco de Quiroga served as a judge in Spanish-occupied Oran from 1520 to 1526. By 1528 he found himself back in Spain at the royal court where he moved among powerful and influential people. There he befriended the Cardinal of Toledo and also Juan Bernal Díaz who was a member of the Council of the Indies which oversaw Spain’s overseas possessions. It was through his connections at court during this time that Vasco de Quiroga came to serve the Spanish king in the New World. By this time he was already approaching 60 years old.

The Spanish colonies in Mexico, then called New Spain, had serious issues regarding governance at the time of Quiroga’s dispatch to the New World. Before the viceroy system was set up, the Spanish overseas territories were governed by audencias. An audencia in Spain in its most traditional sense was strictly a court of justice. In the New World, audencias were established not only so that legal disputes did not have to be sent all the way back to Spain to be heard, but they also performed legislative and executive functions. Audencias consisted of a president and four judges called oidores. The first audencia in the New World was established at Santo Domingo on the island of Hispaniola in 1511. The first one to be established in New Spain, called the Real Audencia de México, was formed in 1528 and was headed by man named Nuño de Guzmán. Guzmán was a former bodyguard of King Charles the Fifth of Spain and founded the Mexican city of Guadalajara during this audencia. Guzmán was also known for his heavy-handed leadership style and ruled over New Spain with absolute authority. To cite an example of his brutality, Guzmán once had a Tarascan Indian king dragged behind a horse and burned at the stake in a quest for information about a gold treasure. To solidify his power, during the time of his presidency of the audencia Guzmán prohibited any direct written communication between Mexico and Spain. Horrified at what had been taking place under Guzmán’s watch, the first Bishop of Mexico, Juan de Zumárraga, wrote a letter to the King of Spain that was encased in wax and put in a wooden cask that was smuggled on a ship headed for the mother country. When the Spanish king heard of Guzmán’s atrocities, he was removed as the head of the audencia and a completely new audencia was formed in 1531. Vasco de Quiroga was part of the second audencia, serving as a judge.

The Spanish colonies in Mexico, then called New Spain, had serious issues regarding governance at the time of Quiroga’s dispatch to the New World. Before the viceroy system was set up, the Spanish overseas territories were governed by audencias. An audencia in Spain in its most traditional sense was strictly a court of justice. In the New World, audencias were established not only so that legal disputes did not have to be sent all the way back to Spain to be heard, but they also performed legislative and executive functions. Audencias consisted of a president and four judges called oidores. The first audencia in the New World was established at Santo Domingo on the island of Hispaniola in 1511. The first one to be established in New Spain, called the Real Audencia de México, was formed in 1528 and was headed by man named Nuño de Guzmán. Guzmán was a former bodyguard of King Charles the Fifth of Spain and founded the Mexican city of Guadalajara during this audencia. Guzmán was also known for his heavy-handed leadership style and ruled over New Spain with absolute authority. To cite an example of his brutality, Guzmán once had a Tarascan Indian king dragged behind a horse and burned at the stake in a quest for information about a gold treasure. To solidify his power, during the time of his presidency of the audencia Guzmán prohibited any direct written communication between Mexico and Spain. Horrified at what had been taking place under Guzmán’s watch, the first Bishop of Mexico, Juan de Zumárraga, wrote a letter to the King of Spain that was encased in wax and put in a wooden cask that was smuggled on a ship headed for the mother country. When the Spanish king heard of Guzmán’s atrocities, he was removed as the head of the audencia and a completely new audencia was formed in 1531. Vasco de Quiroga was part of the second audencia, serving as a judge.

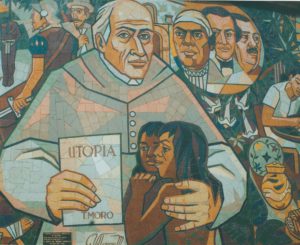

One of the first things that Quiroga did when he arrived in New Spain was to establish a hospital with his own money located in the modern-day Santa Fé area of Mexico City. He called it a “hospital-pueblo” which not only provided medical care but offered food to the hungry, shelter to the homeless and work to those who wanted it. It also served as a church center where indigenous people converted to Christianity. The Hospital-Pueblo of Santa Fé was Quiroga’s first attempt to put to practical use some of the principles of the European Enlightenment. Quiroga was very much influenced by the works of Sir Thomas More, the Lord Chancellor under England’s King Henry the Eighth, and read Bishop Zumárraga’s copy of More’s 1516 book Utopia about a fictional perfect society existing on an island off the coast of South America. In More’s Utopia, the government of the fictional island was a welfare state where private property was abolished and there existed community warehouses to supply goods. Everyone worked, but only 6 hours a day, and women had equal legal status with men. Hospitals were free and freedom of religion existed throughout Utopia, with most people either being monotheists or worshippers of the moon, the sun, the planets or ancestors. Slavery existed, but only as a form of punishment or a way to deal with foreigners. Quiroga was so taken by More’s Utopia that he translated it into Spanish. A few years later he would apply some of More’s philosophy on a larger scale when the political situation in New Spain changed again.

One of the first things that Quiroga did when he arrived in New Spain was to establish a hospital with his own money located in the modern-day Santa Fé area of Mexico City. He called it a “hospital-pueblo” which not only provided medical care but offered food to the hungry, shelter to the homeless and work to those who wanted it. It also served as a church center where indigenous people converted to Christianity. The Hospital-Pueblo of Santa Fé was Quiroga’s first attempt to put to practical use some of the principles of the European Enlightenment. Quiroga was very much influenced by the works of Sir Thomas More, the Lord Chancellor under England’s King Henry the Eighth, and read Bishop Zumárraga’s copy of More’s 1516 book Utopia about a fictional perfect society existing on an island off the coast of South America. In More’s Utopia, the government of the fictional island was a welfare state where private property was abolished and there existed community warehouses to supply goods. Everyone worked, but only 6 hours a day, and women had equal legal status with men. Hospitals were free and freedom of religion existed throughout Utopia, with most people either being monotheists or worshippers of the moon, the sun, the planets or ancestors. Slavery existed, but only as a form of punishment or a way to deal with foreigners. Quiroga was so taken by More’s Utopia that he translated it into Spanish. A few years later he would apply some of More’s philosophy on a larger scale when the political situation in New Spain changed again.

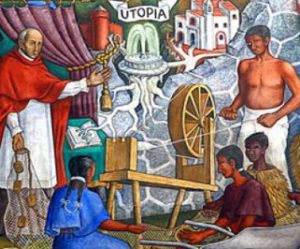

Vasco de Quiroga, who is celebrated today throughout the Mexican state of Michoacán, first arrived in that area in 1533 as a royal inspector right after the Chichimec Indians revolted. Quiroga was overcome with grief at what he had witnessed in Michoacán in the wake of the First Audencia under Nuño de Guzmán. After over a year of inspection, Quiroga was recalled to Mexico City and resumed his role as a judge under the Second Audencia. In 1535 Quiroga wrote a lengthy legal treatise arguing against the Spanish Crown’s limited reversal of a 1530 law abolishing Indian slavery. This writing, called “Información en Derecho,” also was the first written account of Quiroga’s different approach for dealing with the Indians. He made the case that the rights of the indigenous should be respected and that instead of being so heavy handed with the Indians that they should be gathered together in towns to work in specific crafts and industries. In these controlled communities, the Indians could be better governed and guided. The way these towns would function would loosely be based on Thomas More’s Utopia. The basic unit would be the family. 30 families would be grouped and overseen by someone holding the office of jurado, which corresponded to More’s office of Syphogrant. Groups of 10 jurados would be governed by a regidor, which was equal to the Utopian office of Philarch. Above the regidores would be two alcaldes menores and one alcalde mayor, which corresponded to the idea of a Utopian prince in More’s work. Quiroga added an extra layer to the Englishman’s hierarchy, though; while all the aforementioned offices were to be held by the indigenous Tarascan Indians, on top of it all was a corregidor, a Spanish mayor of the town who answered to royal authority. Quiroga already had a literal and figurative “ear of the emperor” back in Spain and his plans were met with enthusiasm.

Vasco de Quiroga, who is celebrated today throughout the Mexican state of Michoacán, first arrived in that area in 1533 as a royal inspector right after the Chichimec Indians revolted. Quiroga was overcome with grief at what he had witnessed in Michoacán in the wake of the First Audencia under Nuño de Guzmán. After over a year of inspection, Quiroga was recalled to Mexico City and resumed his role as a judge under the Second Audencia. In 1535 Quiroga wrote a lengthy legal treatise arguing against the Spanish Crown’s limited reversal of a 1530 law abolishing Indian slavery. This writing, called “Información en Derecho,” also was the first written account of Quiroga’s different approach for dealing with the Indians. He made the case that the rights of the indigenous should be respected and that instead of being so heavy handed with the Indians that they should be gathered together in towns to work in specific crafts and industries. In these controlled communities, the Indians could be better governed and guided. The way these towns would function would loosely be based on Thomas More’s Utopia. The basic unit would be the family. 30 families would be grouped and overseen by someone holding the office of jurado, which corresponded to More’s office of Syphogrant. Groups of 10 jurados would be governed by a regidor, which was equal to the Utopian office of Philarch. Above the regidores would be two alcaldes menores and one alcalde mayor, which corresponded to the idea of a Utopian prince in More’s work. Quiroga added an extra layer to the Englishman’s hierarchy, though; while all the aforementioned offices were to be held by the indigenous Tarascan Indians, on top of it all was a corregidor, a Spanish mayor of the town who answered to royal authority. Quiroga already had a literal and figurative “ear of the emperor” back in Spain and his plans were met with enthusiasm.

As mentioned earlier, Vasco de Quiroga was not a priest. In 1538, however, he was “fast tracked” by the king of Spain and the pope himself, and made Bishop of Michoacán, a newly established position. As bishop, Quiroga thus set out to implement Utopia. He set up the industry-specific towns, taught the Tarascans limited self-government and converted the remaining non-believing Indians to Christianity. Quiroga was also known as a “man of the people” in that he spent much time visiting the small towns and villages throughout his bishopric employing a gentle hands-on approach, even well into his 90s. The brutal days of Spanish rule under Nuño de Guzmán had been replaced by a peace and prosperity that was only a dream under the First Audencia. Quiroga went on to found another hospital-pueblo in Michoacán and the Colegio de San Nicolás, which today is one of the oldest institutions of higher learning in the Americas. On his death, he bequeathed over 600 books from his personal collection to San Nicolás. The college and the fact that the Tarascan villages to this day still produce some of the most beautiful crafts in all of Mexico testify to Quiroga’s effectiveness. To this day, the descendants of his flock endearingly refer

As mentioned earlier, Vasco de Quiroga was not a priest. In 1538, however, he was “fast tracked” by the king of Spain and the pope himself, and made Bishop of Michoacán, a newly established position. As bishop, Quiroga thus set out to implement Utopia. He set up the industry-specific towns, taught the Tarascans limited self-government and converted the remaining non-believing Indians to Christianity. Quiroga was also known as a “man of the people” in that he spent much time visiting the small towns and villages throughout his bishopric employing a gentle hands-on approach, even well into his 90s. The brutal days of Spanish rule under Nuño de Guzmán had been replaced by a peace and prosperity that was only a dream under the First Audencia. Quiroga went on to found another hospital-pueblo in Michoacán and the Colegio de San Nicolás, which today is one of the oldest institutions of higher learning in the Americas. On his death, he bequeathed over 600 books from his personal collection to San Nicolás. The college and the fact that the Tarascan villages to this day still produce some of the most beautiful crafts in all of Mexico testify to Quiroga’s effectiveness. To this day, the descendants of his flock endearingly refer  to Quiroga as Tata Vasco or Father Vasco. Some people, though, look past the nearly mythical elements of the Quiroga story and have recently examined the kind octogenarian bishop more closely. Indigenous activists scorn the Tata Vasco legend and see the man as a tool of the Spanish Conquest and an instrument in the eradication of native cultures and languages. As a supposed follower of the Enlightenment, Quiroga did not guarantee freedom of religion in his newly formed communities. While he may have ended the bloodshed and the physical brutality inflicted on the Indians, Quiroga was part of a larger cultural genocide, critics will argue. Those who counter this critical view see a wise, older man faced with the dire situations of his times endeavoring to do the best with what he was given to deal with. Quiroga did not create the Conquest, only worked within the system to right some of the wrongs of the past and move forward with new tools into a new age. Whichever side one may be on, the contributions of Tata Vasco to the modern nation of Mexico are indisputable and enduring. Over 400 years later he still remains a beloved figure and a champion of the common people of Mexico.

to Quiroga as Tata Vasco or Father Vasco. Some people, though, look past the nearly mythical elements of the Quiroga story and have recently examined the kind octogenarian bishop more closely. Indigenous activists scorn the Tata Vasco legend and see the man as a tool of the Spanish Conquest and an instrument in the eradication of native cultures and languages. As a supposed follower of the Enlightenment, Quiroga did not guarantee freedom of religion in his newly formed communities. While he may have ended the bloodshed and the physical brutality inflicted on the Indians, Quiroga was part of a larger cultural genocide, critics will argue. Those who counter this critical view see a wise, older man faced with the dire situations of his times endeavoring to do the best with what he was given to deal with. Quiroga did not create the Conquest, only worked within the system to right some of the wrongs of the past and move forward with new tools into a new age. Whichever side one may be on, the contributions of Tata Vasco to the modern nation of Mexico are indisputable and enduring. Over 400 years later he still remains a beloved figure and a champion of the common people of Mexico.

REFERENCES (This is not a formal bibliography)

Tata Vasco: Un Gran Reformador del Siglo XVI by Paul L. Callens (in Spanish)

Don Vasco de Quiroga Obispo de Utopía by Benjamín Jarnés (in Spanish)

Sir Thomas More in New Spain: A Utopian Adventure of the Renaissance by Zilvio Zavala