Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

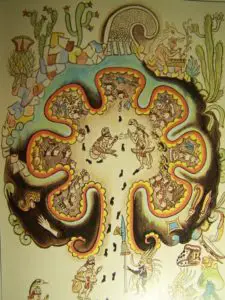

Imagine this scene: Tens of thousands of people on the move, a caravan over 12 miles long. They are headed out of the northern deserts of Mexico and into the more temperate and fertile highlands in search of a new home. At the front of the caravan are priests, warriors and nobles, and as if part of a grand procession at the head of it all is a feathered and cloaked effigy of a god. The priests claim that the god has spoken to them in dreams or has whispered directions to them. There is no doubt among the people that this supernatural being has guided them and protected them on their long and danger-filled journey. The god is Huitzilopochtli. The people are the Aztecs. The time is the early part of the 1300s, about two centuries before the Spanish conquistadors arrived on Mexican shores.

Imagine this scene: Tens of thousands of people on the move, a caravan over 12 miles long. They are headed out of the northern deserts of Mexico and into the more temperate and fertile highlands in search of a new home. At the front of the caravan are priests, warriors and nobles, and as if part of a grand procession at the head of it all is a feathered and cloaked effigy of a god. The priests claim that the god has spoken to them in dreams or has whispered directions to them. There is no doubt among the people that this supernatural being has guided them and protected them on their long and danger-filled journey. The god is Huitzilopochtli. The people are the Aztecs. The time is the early part of the 1300s, about two centuries before the Spanish conquistadors arrived on Mexican shores.

The scene describes the Aztec myth of their own origins. The Aztecs were once a fierce and nomadic people who lived in a place called Aztlán, located somewhere north of central Mexico before they migrated south to what the Spanish would come to know as the homeland of the Aztec Empire. Please see Mexico Unexplained Episode #18 to learn more about the stories about the land of Aztlán. How much of this origin myth is real or made up for political or propaganda purposes is still unknown, but linguistically, the Aztecs are connected to the peoples of the American Southwest. The migration was probably a real one, but embellished later, as most epic stories like this are. Central to the migration myth is the god Huitzilopochtli, who was once a minor god but grew more important to the Aztecs over time. By the time of the Spanish Conquest much of the Aztec Empire’s activities were centered around this god, who was credited with helping and protecting the Aztecs, but demanded a great deal in return.

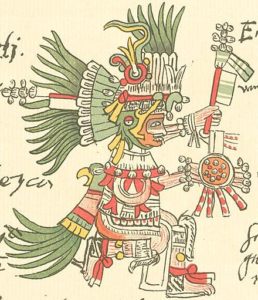

It’s often difficult for people who practice western religions such as Christianity, Islam and Judaism, to imagine a religious system without definitive creation stories or fixed roles played by the major characters in their religion. For example, in the Christian Bible, there is one and only one version of the creation of the Universe. In Islam, there is one great prophet and his role in that religion is concrete and not open to interpretation. The religions of ancient Mexico, between cultures and sometimes within a culture itself, had a great degree of variability. In one religious tradition, for example, there may be several creation stories and the principals within those stories may take on different roles or have different attributes ascribed to them. So it was with the religious beliefs of the Nahua peoples of central Mexico in pre-Hispanic times. Among different subgroups of the Aztecs, there were different often conflicting stories about one of their main gods, Huitzilopochtli. In a very early myth, Huitzilopochtli was the son of the androgynous god Ometeotl, who, in primordial times, split into male and female aspects to give birth to the war god. The second most popular story about Huitzilopochtli was that he was the smallest of 4 children of the creator gods, Tonacatecutli and Tonacacihuatl. The creator gods wanted order on the earth, so they charged Huitzilopochtli and his brother, Quetzalcoatl, with creating everything from fire to human beings. In another widely accepted story, perhaps the most popular at the time, Huitzilopochtli was the son of Coatlicue, the great snake-skirted goddess who lived on Mount Coatepec near the ancient Toltec city of Tula. When Coatlicue was sweeping and cleaning the top of the mountain, a ball of hummingbird feathers fell from the sky and impregnated her. The result of the pregnancy was the god Huitzilopochtli who was born armed and ready for battle. As an aside, the very name Huitzilopochtli, comes from two words meaning “hummingbird,” huitzilin, and “south,” or “left-hand side,” opochtli. There were several other stories about this god, too, and as the Aztec Empire grew and as subjugated peoples converted to the new religion of their Aztec overlords, there was a push for more standardization of the Aztec belief system. The emperor who recognized the need for more standardization for everything throughout the

It’s often difficult for people who practice western religions such as Christianity, Islam and Judaism, to imagine a religious system without definitive creation stories or fixed roles played by the major characters in their religion. For example, in the Christian Bible, there is one and only one version of the creation of the Universe. In Islam, there is one great prophet and his role in that religion is concrete and not open to interpretation. The religions of ancient Mexico, between cultures and sometimes within a culture itself, had a great degree of variability. In one religious tradition, for example, there may be several creation stories and the principals within those stories may take on different roles or have different attributes ascribed to them. So it was with the religious beliefs of the Nahua peoples of central Mexico in pre-Hispanic times. Among different subgroups of the Aztecs, there were different often conflicting stories about one of their main gods, Huitzilopochtli. In a very early myth, Huitzilopochtli was the son of the androgynous god Ometeotl, who, in primordial times, split into male and female aspects to give birth to the war god. The second most popular story about Huitzilopochtli was that he was the smallest of 4 children of the creator gods, Tonacatecutli and Tonacacihuatl. The creator gods wanted order on the earth, so they charged Huitzilopochtli and his brother, Quetzalcoatl, with creating everything from fire to human beings. In another widely accepted story, perhaps the most popular at the time, Huitzilopochtli was the son of Coatlicue, the great snake-skirted goddess who lived on Mount Coatepec near the ancient Toltec city of Tula. When Coatlicue was sweeping and cleaning the top of the mountain, a ball of hummingbird feathers fell from the sky and impregnated her. The result of the pregnancy was the god Huitzilopochtli who was born armed and ready for battle. As an aside, the very name Huitzilopochtli, comes from two words meaning “hummingbird,” huitzilin, and “south,” or “left-hand side,” opochtli. There were several other stories about this god, too, and as the Aztec Empire grew and as subjugated peoples converted to the new religion of their Aztec overlords, there was a push for more standardization of the Aztec belief system. The emperor who recognized the need for more standardization for everything throughout the  empire was Tlacaelel, a man who lived almost 90 years and ruled for decades. Under the rule of this emperor, the Aztec Triple Alliance was formed and the Aztecs became more expansionistic and militaristic. In Tlacaelel’s religious reforms, the emperor elevated Huitzilopochtli to supreme war god and on par with the three chief gods of the Aztecs at the time: Tezcatlipoca, Tlaloc and Quetzalcoatl. Huitzilopochtli was also made the god of the sun, thus replacing the old solar god of ancient central Mexico, Nanahuatzin. Huitzilopochtli could also shape-shift into his spirit animal, an eagle, and could come to earth at will in this form. The eagle imagery of the god also fit in well with other Aztec myths. The god was also associated with gold, warriors and rulers. Under Emperor Tlacaelel, researchers believe, the Aztec origin stories were also fleshed out and further elaborated. It was during his long reign when the Aztecs started seeing themselves as “the chosen people,” and those who had the special protection of the gods, especially their newly empowered war god Huitzilopochtli, who had been with them all along and who needed to be worshipped and credited for the great successes of the Aztecs on the battlefield. Huitzilopochtli became the official protector of the Aztec people and the patron of the capital city of Tenochtitlan at this time. Under Tlacaelel, “cleaning up” the religion, solidifying the myths and standardizing other aspects of the empire allowed the Aztec imperium to grow and dominate Mexico for years and years to come. The belief in Huitzilopochtli played one of the most important roles in all of this.

empire was Tlacaelel, a man who lived almost 90 years and ruled for decades. Under the rule of this emperor, the Aztec Triple Alliance was formed and the Aztecs became more expansionistic and militaristic. In Tlacaelel’s religious reforms, the emperor elevated Huitzilopochtli to supreme war god and on par with the three chief gods of the Aztecs at the time: Tezcatlipoca, Tlaloc and Quetzalcoatl. Huitzilopochtli was also made the god of the sun, thus replacing the old solar god of ancient central Mexico, Nanahuatzin. Huitzilopochtli could also shape-shift into his spirit animal, an eagle, and could come to earth at will in this form. The eagle imagery of the god also fit in well with other Aztec myths. The god was also associated with gold, warriors and rulers. Under Emperor Tlacaelel, researchers believe, the Aztec origin stories were also fleshed out and further elaborated. It was during his long reign when the Aztecs started seeing themselves as “the chosen people,” and those who had the special protection of the gods, especially their newly empowered war god Huitzilopochtli, who had been with them all along and who needed to be worshipped and credited for the great successes of the Aztecs on the battlefield. Huitzilopochtli became the official protector of the Aztec people and the patron of the capital city of Tenochtitlan at this time. Under Tlacaelel, “cleaning up” the religion, solidifying the myths and standardizing other aspects of the empire allowed the Aztec imperium to grow and dominate Mexico for years and years to come. The belief in Huitzilopochtli played one of the most important roles in all of this.

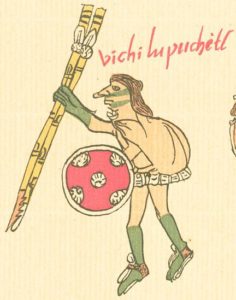

As the god of the sun, Huitzilopochtli was ever-present overhead and a constant visual reminder of the myths the Aztec rulers thought important. He chased his sister, the moon goddess Coyolxauhqui across the sky, and his daily journey to the underworld was usually not alone; according to the official story, he took warriors who died in battle with him in his daily journeys as part of his celestial entourage. After 4 years accompanying Huitzilopochtli across the sky, it was believed, the warriors would return to earth in the form of hummingbirds. Going back to his conception story, with the ball of hummingbird feathers impregnating his mother, Coatlicue, there is a great deal of hummingbird imagery associated with Huitzilopochtli. He is often depicted with a multi-colored head, like a hummingbird, and together with his warrior regalia – a rounded shield, a spear in the form of a serpent and other weapons – he is always adorned with hummingbird feathers. Sometimes Huitzilopochtli is depicted in his spirit animal form, a majestic eagle. In the Aztec codices, or bark paper books, Huitzilopochtli is always very recognizable.

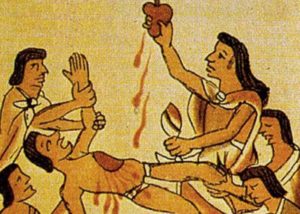

As god of the sun and god of war, Huitzilopochtli demanded blood. Without human sacrifice, the sun would not make its daily journey across the sky and the Aztecs would start to lose on the battlefield. By anyone’s reckoning, if the Aztecs, as the chosen people, and the “children of the sun,” did not provide the god with his human nourishment, the world would end. Also, every 52 years, the Aztecs believed, the world had the possibility of being destroyed in a great cataclysm if the gods were displeased. So, the Aztecs had to maintain the status quo by doing what was asked of them. Most sacrifices were conducted on the top of the Templo Mayor, the great pyramid in the center of the capital city’s civic-ceremonial complex. The top of the temple was divided into two parts, one for Huitzilopochtli, and the other for Tlaloc, the god of rain and fertility. Each god had a wooden carving representing him at the top of the pyramid. Most victims of the sacrifices were war captives, some were slaves. On the stone slabs at the top of the temple, hearts were torn out of living victims with an obsidian knife. While the body of the victim was dismembered and tossed down the steps of the pyramid, the victim’s heart was placed in a special jar called a quauhxicalli, or “eagle’s vase,” and burned. Sometimes pieces of the flesh of the victims were saved for nobles and priests to eat.

As god of the sun and god of war, Huitzilopochtli demanded blood. Without human sacrifice, the sun would not make its daily journey across the sky and the Aztecs would start to lose on the battlefield. By anyone’s reckoning, if the Aztecs, as the chosen people, and the “children of the sun,” did not provide the god with his human nourishment, the world would end. Also, every 52 years, the Aztecs believed, the world had the possibility of being destroyed in a great cataclysm if the gods were displeased. So, the Aztecs had to maintain the status quo by doing what was asked of them. Most sacrifices were conducted on the top of the Templo Mayor, the great pyramid in the center of the capital city’s civic-ceremonial complex. The top of the temple was divided into two parts, one for Huitzilopochtli, and the other for Tlaloc, the god of rain and fertility. Each god had a wooden carving representing him at the top of the pyramid. Most victims of the sacrifices were war captives, some were slaves. On the stone slabs at the top of the temple, hearts were torn out of living victims with an obsidian knife. While the body of the victim was dismembered and tossed down the steps of the pyramid, the victim’s heart was placed in a special jar called a quauhxicalli, or “eagle’s vase,” and burned. Sometimes pieces of the flesh of the victims were saved for nobles and priests to eat.

In addition to the daily sacrifices, which were few in number, the Aztecs had an annual festival to celebrate Huitzilopochtli’s birth every December. “The Feast of the Precious Feathers,” or Panquetzaliztli was held in the 15th month of the ceremonial calendar and could last days or weeks. The ceremonies were led by Huitzolopochtli’s high priest called, in the Nahuatl language of the Aztecs, Quetzalcóatl Totec Tlamacazqui, or in English, “The Feathered Serpent Priest of Our Lord.” This head priest wielded a great deal of power in the Aztec world and only answered to the Aztec emperor or immediate members of the royal family. The celebrations for the war/sun god during the Panquetzaliztli included days of feasting and dancing and other celebratory events happening around Huitzilopochtli’s temple. Commoners offered flowers and quail eggs to the god, and paper banners and garlands decorated the buildings of the Aztec capital city, along with various images of the god. Priests would burn elaborately made, gigantic paper-bark serpents to symbolize Huitzilopochtli’s turquoise serpent spear, the xiuh cóatl. The god required 60 human sacrifices for this annual celebration. As the sacrificial victims for this festival were seen as more special, captives and slaves who were to be offered up to the god were first taken to the sacred springs at Huitzolopochco – in the modern-day Mexico City neighborhood of Churubusco – to be cleansed and purified. To end the celebrations, a huge sculpture of Huitzilopochtli was fashioned out of a paste made of amaranth, honey and maize. The image was adorned, and paraded around the streets of Tenochtitlan in a procession, much like a Catholic saint in a modern-day Mexican fiesta. At the end of the procession, in front of the sacrificial temple, the sculpture would be torn apart and pieces of Huitzilopochtli were given to priests, nobles and up-and-coming warriors to eat. Anyone eating from the sculpture pledged to serve the god for one full year.

In addition to the daily sacrifices, which were few in number, the Aztecs had an annual festival to celebrate Huitzilopochtli’s birth every December. “The Feast of the Precious Feathers,” or Panquetzaliztli was held in the 15th month of the ceremonial calendar and could last days or weeks. The ceremonies were led by Huitzolopochtli’s high priest called, in the Nahuatl language of the Aztecs, Quetzalcóatl Totec Tlamacazqui, or in English, “The Feathered Serpent Priest of Our Lord.” This head priest wielded a great deal of power in the Aztec world and only answered to the Aztec emperor or immediate members of the royal family. The celebrations for the war/sun god during the Panquetzaliztli included days of feasting and dancing and other celebratory events happening around Huitzilopochtli’s temple. Commoners offered flowers and quail eggs to the god, and paper banners and garlands decorated the buildings of the Aztec capital city, along with various images of the god. Priests would burn elaborately made, gigantic paper-bark serpents to symbolize Huitzilopochtli’s turquoise serpent spear, the xiuh cóatl. The god required 60 human sacrifices for this annual celebration. As the sacrificial victims for this festival were seen as more special, captives and slaves who were to be offered up to the god were first taken to the sacred springs at Huitzolopochco – in the modern-day Mexico City neighborhood of Churubusco – to be cleansed and purified. To end the celebrations, a huge sculpture of Huitzilopochtli was fashioned out of a paste made of amaranth, honey and maize. The image was adorned, and paraded around the streets of Tenochtitlan in a procession, much like a Catholic saint in a modern-day Mexican fiesta. At the end of the procession, in front of the sacrificial temple, the sculpture would be torn apart and pieces of Huitzilopochtli were given to priests, nobles and up-and-coming warriors to eat. Anyone eating from the sculpture pledged to serve the god for one full year.

Modern-day researchers see Huitzilopochtli as part of a wider system of control to maintain order and to instill a sense of fear among the common Aztecs and their subjugated peoples. The god inspired terror, awe, reverence and obedience. Huitzilopochtli’s primary association with human sacrifice was perhaps its most troubling aspect in the eyes of the newly arrived Spanish conquerors. The Spanish did what the Spanish did best, and in a few short decades, all evidence of the once mighty Huitzilopochtli was completely erased from the Mexican memory. The god’s replacement, an entirely new system of beliefs and controls, continues to serve and/or subjugate the Mexicans to the present day.

Modern-day researchers see Huitzilopochtli as part of a wider system of control to maintain order and to instill a sense of fear among the common Aztecs and their subjugated peoples. The god inspired terror, awe, reverence and obedience. Huitzilopochtli’s primary association with human sacrifice was perhaps its most troubling aspect in the eyes of the newly arrived Spanish conquerors. The Spanish did what the Spanish did best, and in a few short decades, all evidence of the once mighty Huitzilopochtli was completely erased from the Mexican memory. The god’s replacement, an entirely new system of beliefs and controls, continues to serve and/or subjugate the Mexicans to the present day.

REFERENCES USED (This is not a formal bibliography)

The Mighty Aztecs by Gene S. Stuart

The World of the Aztecs by William H. Prescott

The Aztecs of Mexico by George C. Vaillant