Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

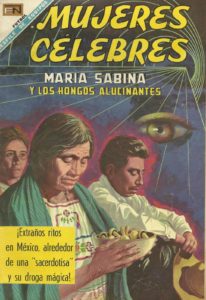

The date was May 13, 1957. The latest edition of Life magazine had just hit the newsstands in America. In the current issue, as part of its “Great Adventures” series, an article written by R. Gordon Wasson appeared titled, “Seeking the Magic Mushroom.” Wasson first traveled to the Mexican state of Oaxaca in June of 1955 where he met a woman named María Sabina who lived in the small town of Huautla de Jiménez, an indigenous Mazatec village about a mile up in the mountainous region of the northeast part of the state. Traveling with a companion, fashion photographer Allan Richardson, Wasson spent weeks in Oaxaca learning about the healing ceremonies called veladas conducted by Sabina and other shamanic healers. The ceremonies all involved a certain type of mushroom that only grew in the summer months called the “landslide mushroom” whose scientific name is Psilocybe mazatecorum. María called these her “saint children.” While there were many shamans using the mushrooms in the veladas, María Sabina, who was almost 60 at the time of Wasson’s visit, had the most refined rituals and the most extensive chants and melodies that accompanied her healing sessions. María referred to this as “The Language.” Gordon Wasson, who was the first non-indigenous person to take part in the ceremonies, would write several more articles in the late 1950s and early 1960s. María Sabina attracted attention of Timothy Leary and other famous people such as Bob Dylan, John Lennon, Mick Jagger and Pete Townshend who traveled to Huautla to see María and have “magic trips” with her. As many people saw Wasson’s article as the first to explore the topic of “magic mushrooms,” this diminutive woman from a remote Oaxacan village has often been credited as being the spark that set off the whole psychedelic movement in the 1960s.

The date was May 13, 1957. The latest edition of Life magazine had just hit the newsstands in America. In the current issue, as part of its “Great Adventures” series, an article written by R. Gordon Wasson appeared titled, “Seeking the Magic Mushroom.” Wasson first traveled to the Mexican state of Oaxaca in June of 1955 where he met a woman named María Sabina who lived in the small town of Huautla de Jiménez, an indigenous Mazatec village about a mile up in the mountainous region of the northeast part of the state. Traveling with a companion, fashion photographer Allan Richardson, Wasson spent weeks in Oaxaca learning about the healing ceremonies called veladas conducted by Sabina and other shamanic healers. The ceremonies all involved a certain type of mushroom that only grew in the summer months called the “landslide mushroom” whose scientific name is Psilocybe mazatecorum. María called these her “saint children.” While there were many shamans using the mushrooms in the veladas, María Sabina, who was almost 60 at the time of Wasson’s visit, had the most refined rituals and the most extensive chants and melodies that accompanied her healing sessions. María referred to this as “The Language.” Gordon Wasson, who was the first non-indigenous person to take part in the ceremonies, would write several more articles in the late 1950s and early 1960s. María Sabina attracted attention of Timothy Leary and other famous people such as Bob Dylan, John Lennon, Mick Jagger and Pete Townshend who traveled to Huautla to see María and have “magic trips” with her. As many people saw Wasson’s article as the first to explore the topic of “magic mushrooms,” this diminutive woman from a remote Oaxacan village has often been credited as being the spark that set off the whole psychedelic movement in the 1960s.

María Sabina was born outside the town of Huautla, Oaxaca sometime in the mid-1890s. Records created later by church officials put her birthdate as July 22, 1894. María and her sister were exposed to shamanism at a young age. The girls’ grandfather and great grandfather were both shamans. At night, she and her sister would hear the chants and ceremonies of the shamans as they went to sleep. Before reaching her teenage years, María began taking mushrooms on her own to go into her own altered states of consciousness and slowly refined her craft as she entered adulthood. Perhaps to discourage others from taking up a craft she held so close to her, María would explain in an interview later in her life where she thought her abilities really came from. She spoke of a time a Catholic bishop visited her:

“The Bishop advised me to initiate my children into the Wisdom. I have. I told him that the color of the skin or the eyes can be inherited, including the manner of crying or of smiling, but the same can’t be done with wisdom. Wisdom can’t be inherited. Wisdom is brought with one from birth. My wisdom can’t be taught; that’s why I say that nobody taught me the Language, because it is the Language the saint children speak upon entering my body. Whoever isn’t born to be wise can’t attain the Language although they do many vigils. Who could teach Language like that? My daughter Apolonia just helps me to pray or to repeat my Language during the vigils. She speaks and says what I ask her to, but she isn’t a wise woman; she wasn’t born with that destiny.” “Apolonia and Victoria, my two daughters, will never be Wise Women.” “Not everyone can be wise. I make that clear to people.”

“The Bishop advised me to initiate my children into the Wisdom. I have. I told him that the color of the skin or the eyes can be inherited, including the manner of crying or of smiling, but the same can’t be done with wisdom. Wisdom can’t be inherited. Wisdom is brought with one from birth. My wisdom can’t be taught; that’s why I say that nobody taught me the Language, because it is the Language the saint children speak upon entering my body. Whoever isn’t born to be wise can’t attain the Language although they do many vigils. Who could teach Language like that? My daughter Apolonia just helps me to pray or to repeat my Language during the vigils. She speaks and says what I ask her to, but she isn’t a wise woman; she wasn’t born with that destiny.” “Apolonia and Victoria, my two daughters, will never be Wise Women.” “Not everyone can be wise. I make that clear to people.”

During her practice, María would become a certain aspect of her “saint children” and each aspect would have chants or songs – her “Language” – to go along with it. Independent scholar and writer Henry Munn went to Huautla in 1965 and identified the many aspects which appeared in María’s ceremonies. The long list includes Eagle Woman, Clock Woman, Opossum Woman, Hummingbird Woman, Whirling Woman of Colors, Shooting Star Woman, The Ocean, The Woman of the Flowing Water, Root Woman, Clown Woman, Warrior Woman or Book Woman. Each served a specific function or appeared through the shaman to conduct specific healings. María often emphasized that she did not practice what is termed as “sorcery.” She used her mushrooms in conjunction with various aspects of the Catholic religion, including icons, traditional prayers and used of candles. In an interview from the early 1970s, María stated:

“For me sorcery and curanderismo (folk medicine) are inferior tasks. The sorcerers and curanderos have their own language as well, but it is different from mine. They ask favors from Chicon Nindó. I ask them of God the Christ, from Saint Peter, from Mary Magdalene and from Guadalupe. The mushrooms have power because they are the flesh of God. And those that believe are healed. Those that do not believe are not healed.”

The typical repertoire of a Mazatec sorcerer or curandero includes things such as macaw feathers, cacao beans, incense made of the sap of the copal tree, tobacco and turkey eggs, because they are more powerful than hen’s eggs. María only used the mushrooms she endearingly called “the little saints” and candles she made herself. The formal church authorities in the area did not condemn the practice.

The typical repertoire of a Mazatec sorcerer or curandero includes things such as macaw feathers, cacao beans, incense made of the sap of the copal tree, tobacco and turkey eggs, because they are more powerful than hen’s eggs. María only used the mushrooms she endearingly called “the little saints” and candles she made herself. The formal church authorities in the area did not condemn the practice.

María Sabina’s chants are well documented, mostly due to the work of a man named Alvaro Estrada who visited Huautla de Jiménez between 1955 and 1970 and compiled dozens of recordings he made of María’s veladas. Her chants were translated into Spanish and then into English and released in a book titled María Sabina, Her Life and Chants. Each line always ends with a word that translates to “says” or “he/she said.” Here is a sample chant, translated into English:

“I am a clean woman, says

I am a well-prepared woman, says

I am a woman who looks into the insides of things, says

I am a woman who looks into the insides of things, says

I am a woman who looks into the insides of things, says

I am a woman who looks into the insides of things, says

I am the woman of light, says

I am the woman of light, says

I am the woman of light, says

I am the woman of the day, says

Ah, Jesus Christ, says

I am a morning star woman, says

I am a morning star woman, says

I am the God Star Woman, says

I am the Cross Star Woman, says

I am the Moon Woman, says

I am a woman laborer, says

Father Jesus Christ, says

I am a woman of heaven, says

I am a woman of heaven, says

Ah, Jesus Christ, says

I am the woman of the great expanse of the waters, says

I am the woman of the expanse of the divine sea, says

Because I can go up to heaven, says

Because I can go over the great expanse of the waters, says

Because I can go over the expanse of the divine sea, says

Calmly, says

Without mishap, says

With sap, says

With dew, says.”

After visits by famous musicians and those prominent members of the ‘60s counterculture, the small town of Huautla became inundated with people who were seeking the higher level of consciousness supposedly attained through María Sabina’s mushroom ceremonies. Again, in her own words, María states:

“For a time there came young people of one and the other sex, long-haired, with strange clothes. They wore shirts of many colors and used necklaces. A lot came. Some of these young people sought me out for me to stay up with the ‘Little One Who Springs Forth.’ ‘We come in search of God,’ they said. It was difficult for me to explain to them that the vigils weren’t done from the simple desire to find God, but were done with the sole purpose of curing the sicknesses that our people suffer from. Later I found out that the young people with long hair didn’t need me to eat the ‘little things.’ Fellow Mazatecs weren’t lacking who, to get a few centavos for food, sold the saint children to the young people. In their turn, the young people ate them wherever they liked: it was the same to them if they chewed them up seated in the shade of a coffee tree or on a cliff along some trail in the woods.”

“For a time there came young people of one and the other sex, long-haired, with strange clothes. They wore shirts of many colors and used necklaces. A lot came. Some of these young people sought me out for me to stay up with the ‘Little One Who Springs Forth.’ ‘We come in search of God,’ they said. It was difficult for me to explain to them that the vigils weren’t done from the simple desire to find God, but were done with the sole purpose of curing the sicknesses that our people suffer from. Later I found out that the young people with long hair didn’t need me to eat the ‘little things.’ Fellow Mazatecs weren’t lacking who, to get a few centavos for food, sold the saint children to the young people. In their turn, the young people ate them wherever they liked: it was the same to them if they chewed them up seated in the shade of a coffee tree or on a cliff along some trail in the woods.”

Later in life María had regrets about opening up her ceremonies to foreigners. She didn’t think anything bad would come of it, but in addition to the overwhelming attention she received and a sort of disrespect of the “old ways” she experienced, María felt that her “little ones”, the mushrooms themselves, had lost their power with their widespread use and misuse. In an interview María conducted when she was well into her 70s, she stated:

“Before Wasson, I felt that the saint children elevated me. I don’t feel like that anymore. The force has diminished. If the foreigners had not come, the ‘saint children’ would have kept their power. Many years ago when I was a child, they grew everywhere. They grew around the house; those weren’t used in the vigils, because if human eyes see them they invalidate their purity and strength. One had to go to distant places to search for them, where they were out of reach of human sight.”

“Before Wasson, I felt that the saint children elevated me. I don’t feel like that anymore. The force has diminished. If the foreigners had not come, the ‘saint children’ would have kept their power. Many years ago when I was a child, they grew everywhere. They grew around the house; those weren’t used in the vigils, because if human eyes see them they invalidate their purity and strength. One had to go to distant places to search for them, where they were out of reach of human sight.”

As María’s world changed around her because of her notoriety, she started to attract the attention of local authorities. What exactly was she doing in these ceremonies? Was she simply a peddler of illegal drugs? She had to appear before government officials several times to explain herself, sometimes far away. The local townsfolk did not like all the attention that their village received from both the government and the foreigners who had been arriving in Huautla in increasing numbers. The attention María was attracting disrupted life in the small town and completely altered the social dynamics in Huautla. María’s time in her native town ended with the villagers tearing down her house and running her off. After spending time away, María was eventually allowed to return to Huautla where she died in 1985 at the age of 91.