Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

In a dark and damp mountainside cave in central Mexico, a young Italian Augustinian friar named Sebastián de Tolentino covered his nose with the fringe of his cloak. His companion, Brother Nicolás Perea did the same. The stench of blood from human sacrifices was too much for the two men to bear. They had both been sent by their order to evangelize this region of New Spain and had heard about the pilgrimages the local people had made to these caves, the caves dedicated to an aspect of the Aztec god Tezcatlipoca, also called “The Smoking Mirror.” The year was 1537 and the place was near the modern village of Chalma in the state of Mexico. The friars approached a mysterious figure at the end of one of the main caves, it was a large, black cylindrical monolith, a carved likeness of Tezcatlipoca about the size of a man. The two Europeans felt somewhat afraid, as if they were making first contact with an alien or demonic presence. The brothers left the cave and returned to their monastery nearby to regroup and formulate a plan. The two friars reasoned that the key to claiming the surrounding country for Christendom would depend on the destruction of that idol in the cave. They vowed to return to the cave three days later with implements to smash the idol, to literally and figuratively break the power it had over the local people. The monks spent a few days in prayer and contemplation before embarking on their trek. By the time they had reached the base of the small mountain in which the caves were located they had realized that something important had happened as there was a great commotion among the pilgrims who had come to visit the monolith statue. From their limited knowledge of the local language, Brothers Sebastián and Nicolás had understood that something happened to the statue, so they ascended the rocky crags to the cave to have a look for themselves. The two fell to their knees when they saw the sight: in the place of the pagan black monolith was a crucifix. On the crucifix was a black rendition of Jesus. Nothing remained of the life-size idol, except for fine shards and rubble around the large crucifix. The Augustinian brothers believed they had witnessed a miracle and now had their powerful tool to convert the Indians.

In a dark and damp mountainside cave in central Mexico, a young Italian Augustinian friar named Sebastián de Tolentino covered his nose with the fringe of his cloak. His companion, Brother Nicolás Perea did the same. The stench of blood from human sacrifices was too much for the two men to bear. They had both been sent by their order to evangelize this region of New Spain and had heard about the pilgrimages the local people had made to these caves, the caves dedicated to an aspect of the Aztec god Tezcatlipoca, also called “The Smoking Mirror.” The year was 1537 and the place was near the modern village of Chalma in the state of Mexico. The friars approached a mysterious figure at the end of one of the main caves, it was a large, black cylindrical monolith, a carved likeness of Tezcatlipoca about the size of a man. The two Europeans felt somewhat afraid, as if they were making first contact with an alien or demonic presence. The brothers left the cave and returned to their monastery nearby to regroup and formulate a plan. The two friars reasoned that the key to claiming the surrounding country for Christendom would depend on the destruction of that idol in the cave. They vowed to return to the cave three days later with implements to smash the idol, to literally and figuratively break the power it had over the local people. The monks spent a few days in prayer and contemplation before embarking on their trek. By the time they had reached the base of the small mountain in which the caves were located they had realized that something important had happened as there was a great commotion among the pilgrims who had come to visit the monolith statue. From their limited knowledge of the local language, Brothers Sebastián and Nicolás had understood that something happened to the statue, so they ascended the rocky crags to the cave to have a look for themselves. The two fell to their knees when they saw the sight: in the place of the pagan black monolith was a crucifix. On the crucifix was a black rendition of Jesus. Nothing remained of the life-size idol, except for fine shards and rubble around the large crucifix. The Augustinian brothers believed they had witnessed a miracle and now had their powerful tool to convert the Indians.

Whether you choose believe in what happened in that cave in the remote area of New Spain, the Black Christ of Chalma – in Spanish El Señor de Chalma – still exists today and the shrine dedicated to Him is the second most popular religious destination in Mexico, right behind the Basilica of the Virgin of Guadalupe. The modern day town of Chalma is a small community in the Mexican state of Mexico about 40 miles from the state capital of Toluca and about 60 miles from Mexico City. Many Mexican Catholics believe that three visits to Chalma are necessary to have one’s specific prayers answered and the small town becomes inundated with the faithful around Easter when hundreds of thousands of people, mostly on foot from neighboring states walk to the shrine in hopes of being on the receiving end of a miracle.

Whether you choose believe in what happened in that cave in the remote area of New Spain, the Black Christ of Chalma – in Spanish El Señor de Chalma – still exists today and the shrine dedicated to Him is the second most popular religious destination in Mexico, right behind the Basilica of the Virgin of Guadalupe. The modern day town of Chalma is a small community in the Mexican state of Mexico about 40 miles from the state capital of Toluca and about 60 miles from Mexico City. Many Mexican Catholics believe that three visits to Chalma are necessary to have one’s specific prayers answered and the small town becomes inundated with the faithful around Easter when hundreds of thousands of people, mostly on foot from neighboring states walk to the shrine in hopes of being on the receiving end of a miracle.

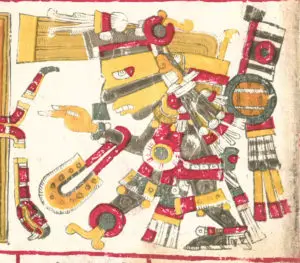

Anthropologists and historians believe that the cave in which the Black Christ appeared was dedicated to an aspect or form of the Aztec “smoking mirror” god Tezcatlipoca called Oxtoteotl which has been associated with a wide range of concepts including discord, temptations, war, evil sorcery, jaguars, the night winds, the night sky, the earth, hurricanes and volcanic glass, also called obsidian. The “Smoking Mirror” nickname of the god comes the Aztec term for the volcanic glass polished to a high sheen used in divination. The earliest known formal Spanish description of the caves of Chalma came from the Jesuit priest Francisco de Florencia who called the place the Cave of Ostoc Teotl, which translates to “The Dark Lord of the Cave.” Prior to the Conquest the caves around Chalma had deep spiritual significance and attracted pilgrims from throughout the Aztec Empire. Many of the rituals and celebrations surrounding the pilgrimage to the caves still survive in some form of another today. The Jesuit Florencia described people arriving to the area wearing flowers and carrying incense, and bathing in the local springs and streams as part of a cleansing ritual. Tezcatlipoca devotees would also drink a type of purified holy water before entering the caves. Human sacrifice was not uncommon here, but, of course, it did not survive the Spanish takeover. No one knows who carved the large black monolith which was venerated in the cave, how it got there or how old it was. As it was allegedly destroyed we will probably never know anything more about it.

Anthropologists and historians believe that the cave in which the Black Christ appeared was dedicated to an aspect or form of the Aztec “smoking mirror” god Tezcatlipoca called Oxtoteotl which has been associated with a wide range of concepts including discord, temptations, war, evil sorcery, jaguars, the night winds, the night sky, the earth, hurricanes and volcanic glass, also called obsidian. The “Smoking Mirror” nickname of the god comes the Aztec term for the volcanic glass polished to a high sheen used in divination. The earliest known formal Spanish description of the caves of Chalma came from the Jesuit priest Francisco de Florencia who called the place the Cave of Ostoc Teotl, which translates to “The Dark Lord of the Cave.” Prior to the Conquest the caves around Chalma had deep spiritual significance and attracted pilgrims from throughout the Aztec Empire. Many of the rituals and celebrations surrounding the pilgrimage to the caves still survive in some form of another today. The Jesuit Florencia described people arriving to the area wearing flowers and carrying incense, and bathing in the local springs and streams as part of a cleansing ritual. Tezcatlipoca devotees would also drink a type of purified holy water before entering the caves. Human sacrifice was not uncommon here, but, of course, it did not survive the Spanish takeover. No one knows who carved the large black monolith which was venerated in the cave, how it got there or how old it was. As it was allegedly destroyed we will probably never know anything more about it.

When the Black Jesus appeared in the cave to the Augustinian friars, a mass conversion occurred, and thousands of people in the surrounding area converted to Christianity almost instantaneously. Visits to the shrine in the cave continued almost uninterrupted, but the people began coming to see a new god and to receive favors from a new divine entity. According to the popular story, when Tezcatlipoca left, so did the jaguars with which he was associated, as well as other predatory animals, thus making the journey to Chalma safer for the pilgrims. Sometime in the 17th Century the entrance to main cave was enlarged and a small shrine to Saint Michael was installed. Almost 150 years after the Christ appeared, two other Augustinian brothers – Bartolomé de Jesús María and Juan de San José – founded a monastery near the cave site which attended to the many pilgrims visiting the caves. Later, a church was built near the monastery and the image of the Black Christ was moved out of the cave and to the church. The sanctuary complex has been modified over the years with various remodels and expansions. Sometime in the 1700s the shrine complex suffered a massive fire and the original Christ figure was damaged in that fire. A new figure was created in what remained of the old and that newly modified Black Christ can be seen in the church of Chalma today. In 1783, King Charles the Third of Spain, who took great interest in Chalma, put the shrine directly under his protection. With patronage from the king came many more improvements to the shrine, including a new

When the Black Jesus appeared in the cave to the Augustinian friars, a mass conversion occurred, and thousands of people in the surrounding area converted to Christianity almost instantaneously. Visits to the shrine in the cave continued almost uninterrupted, but the people began coming to see a new god and to receive favors from a new divine entity. According to the popular story, when Tezcatlipoca left, so did the jaguars with which he was associated, as well as other predatory animals, thus making the journey to Chalma safer for the pilgrims. Sometime in the 17th Century the entrance to main cave was enlarged and a small shrine to Saint Michael was installed. Almost 150 years after the Christ appeared, two other Augustinian brothers – Bartolomé de Jesús María and Juan de San José – founded a monastery near the cave site which attended to the many pilgrims visiting the caves. Later, a church was built near the monastery and the image of the Black Christ was moved out of the cave and to the church. The sanctuary complex has been modified over the years with various remodels and expansions. Sometime in the 1700s the shrine complex suffered a massive fire and the original Christ figure was damaged in that fire. A new figure was created in what remained of the old and that newly modified Black Christ can be seen in the church of Chalma today. In 1783, King Charles the Third of Spain, who took great interest in Chalma, put the shrine directly under his protection. With patronage from the king came many more improvements to the shrine, including a new  elaborately carved altar, beautiful works of art depicting the Virgin of Guadalupe and Saint Michael, and a new neoclassical façade for the church. King Charles proclaimed that the shrine was to be called El Convento Real y Sanctuario de Nuestro Señor Jesucristo y San Miguel de las Cuevas de Chalma, which in English translates to The Royal Monastery and Sanctuary of Our Lord Jesus Christ and Saint Michael of the Caves of Chalma. While the shrine complex is located on the canyon floor, the cliffs and caves overlooking the complex are still considered holy. There are large crosses on the cliffs overlooking the town which are taken down during various times of the year to be rededicated in the Chalma church, a custom that dates back to at least the time of the King Charles patronage.

elaborately carved altar, beautiful works of art depicting the Virgin of Guadalupe and Saint Michael, and a new neoclassical façade for the church. King Charles proclaimed that the shrine was to be called El Convento Real y Sanctuario de Nuestro Señor Jesucristo y San Miguel de las Cuevas de Chalma, which in English translates to The Royal Monastery and Sanctuary of Our Lord Jesus Christ and Saint Michael of the Caves of Chalma. While the shrine complex is located on the canyon floor, the cliffs and caves overlooking the complex are still considered holy. There are large crosses on the cliffs overlooking the town which are taken down during various times of the year to be rededicated in the Chalma church, a custom that dates back to at least the time of the King Charles patronage.

As the second most visited religious site in Mexico, Chalma receives over 2 million visitors per year. Chalma is your typical Mexican pilgrimage site. Outside the sanctuary complex we find almost a carnival atmosphere with vendors hawking religious trinkets, and food of all kinds being sold, from fast food and snacks to elaborate sit-down meals. There is a place on the path to the river outside the church where people can leave folk art paintings called retablos detailing in graphic form thanks for miracles received. Alongside the retablos are other typical offerings of thanks: locks of hair, photos, and so on. This wall has to be cleaned periodically as it gets crowded with devotional items from the thousands and thousands of miracles and prayers granted which are attributed to the Black Christ of Chalma.

Pilgrimages to Chalma are often a group effort. Villages or towns may sponsor a small contingent from their municipality to make the trek to Chalma. Although there is now a paved road leading through the winding canyons and rugged terrain to get to the sanctuary, many pilgrims prefer to make the journey on foot as they have done for hundreds of years. When they get to Chalma pilgrims participate in a number of ritual activities. Many wear flowers, much as the Aztecs did. Many also dance at the shrine, which is another ritualistic behavior traced back to the pre-Hispanic times. Just as the Aztecs had done, visitors to Chalma purify themselves in the springs and small streams surrounding the caves and rocky outcrops. After bathing, it is said, one is spiritually clean and can wear a crown of flowers to dance at the shrine. Of special note is a spring that comes directly out of a centuries-old cypress tree. Many women believe that the water from the spring will help with fertility and they splash it all over their bodies. During festival days, primarily around Easter, artists in the town of Chalma construct intricate panels comprised of flowers and seeds. The townsfolk also make arches contructed of colorful tissue paper or papier-mache. During festival days all the streets of Chalma are filled with people and vehicles are prohibited. The whole town explodes in celebration.

Pilgrimages to Chalma are often a group effort. Villages or towns may sponsor a small contingent from their municipality to make the trek to Chalma. Although there is now a paved road leading through the winding canyons and rugged terrain to get to the sanctuary, many pilgrims prefer to make the journey on foot as they have done for hundreds of years. When they get to Chalma pilgrims participate in a number of ritual activities. Many wear flowers, much as the Aztecs did. Many also dance at the shrine, which is another ritualistic behavior traced back to the pre-Hispanic times. Just as the Aztecs had done, visitors to Chalma purify themselves in the springs and small streams surrounding the caves and rocky outcrops. After bathing, it is said, one is spiritually clean and can wear a crown of flowers to dance at the shrine. Of special note is a spring that comes directly out of a centuries-old cypress tree. Many women believe that the water from the spring will help with fertility and they splash it all over their bodies. During festival days, primarily around Easter, artists in the town of Chalma construct intricate panels comprised of flowers and seeds. The townsfolk also make arches contructed of colorful tissue paper or papier-mache. During festival days all the streets of Chalma are filled with people and vehicles are prohibited. The whole town explodes in celebration.

No one knows how long people have been visiting the area of Chalma seeking guidance and grace from the divine. We know that it goes back at least to the 13th Century with the coming of the Aztec Empire but may even go back before then. Whether one believes the story of how the Black Christ came to be, there is no denying the power and the comfort that the image generates. The origin and original meaning of the venerated black monolith in the cave that preceded it is still unknown. At Chalma we have a miracle, magic and mystery all wrapped into one.

No one knows how long people have been visiting the area of Chalma seeking guidance and grace from the divine. We know that it goes back at least to the 13th Century with the coming of the Aztec Empire but may even go back before then. Whether one believes the story of how the Black Christ came to be, there is no denying the power and the comfort that the image generates. The origin and original meaning of the venerated black monolith in the cave that preceded it is still unknown. At Chalma we have a miracle, magic and mystery all wrapped into one.

REFERENCES (This is not a formal bibliography)

Descripción Histórica, y Moral del yermo de San Miguel, de las cuevas en el Reyno de la Nueva-España, y invención de la milagrosa Imagen de Cristo nuestro Señor Crucificado, que fe venera en ellas by Francisco de Florencia (in Spanish)

El Estado de México by the State of Mexico Department of Tourism (in Spanish)

The Aztecs, the Maya and their Predecessors by Muriel Porter Weaver.

6 thoughts on “The Black Christ of Chalma”

This is extremely interesting ! And is this podcast available in Spanish ? If not, am I permitted to use small parts of it in the course of writing to Facebook friends ?

Hi John, You are more than welcome to use this in any way you want. Sorry that this podcast is not available in Spanish (and sorry it has taken so long for me to get back to you). Cheers.

Wow. VERY interesting.

Indeed. Thanks for listening!

This is a more inclusive history than some of the others I have read, several of which simply copy the material from another site. I was in Chalma in 2012 at Pentecost and witnessed hundreds of danzantes Aztecas dancing in front of, below, and behind the cathedral. Religious groups also refurbished many crosses during that week and re”planted” them on the mountain before Sunday. Pilgrims also came from long distances, many walking, many carrying shrines on their backs, some on their knees.

Thank you very much for sharing that.