Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

The early part of the 21st Century has seen the rise of the home-based DNA testing kit. People who are curious about their ancestors can take a swab from inside their mouths and send off the swab to a lab for analysis. Commercials on television and the internet for the big companies offering DNA-based race/ethnic discovery services emphasize the “wow” or “surprise” factor of getting tested. A red-haired woman, for example, shows her shock at being 15% East Asian. An African-American man is equally surprised when his DNA results show that he is 8% Scandinavian. On YouTube, there are many videos of people revealing their ancestry results to their viewers “live.” A curious amount of Mexican-Americans in this space express a universal surprise that part of their DNA indicates sub-Saharan African origins. For many years the idea of what it meant to be “Mexican” has rested on the idea of mestizaje, or the blend of blood and culture of the Spanish conquerors with the indigenous or Native American population. La Raza Cósmica or simply, La Raza, a term used by many Mexicans and Mexican-Americans alike is usually used to describe the blending of Spanish and Indian to create a new ethnicity entirely, a separate and distinct identity. What is often left out of this “blend” are cultural and genetic influences from Africa, and hence the surprise expressed in the YouTube videos from DNA test result recipients. Not many people are aware that on average, Mexicans have 4% African blood in them, and less is known about African contributions to Mexican culture and history. When the topic of African influence in Mexico comes up, it is often mentioned that any sort of blackness has been “washed out” or has “blended in” to the national culture and gene pool, and historically, little attention has been given to it. As individuals and communities of people with predominately African heritage in Mexico make themselves more widely known to others, there has been a growing awareness of Africa’s continuing contribution to the nation of Mexico and the idea of “Mexicanness.”

The early part of the 21st Century has seen the rise of the home-based DNA testing kit. People who are curious about their ancestors can take a swab from inside their mouths and send off the swab to a lab for analysis. Commercials on television and the internet for the big companies offering DNA-based race/ethnic discovery services emphasize the “wow” or “surprise” factor of getting tested. A red-haired woman, for example, shows her shock at being 15% East Asian. An African-American man is equally surprised when his DNA results show that he is 8% Scandinavian. On YouTube, there are many videos of people revealing their ancestry results to their viewers “live.” A curious amount of Mexican-Americans in this space express a universal surprise that part of their DNA indicates sub-Saharan African origins. For many years the idea of what it meant to be “Mexican” has rested on the idea of mestizaje, or the blend of blood and culture of the Spanish conquerors with the indigenous or Native American population. La Raza Cósmica or simply, La Raza, a term used by many Mexicans and Mexican-Americans alike is usually used to describe the blending of Spanish and Indian to create a new ethnicity entirely, a separate and distinct identity. What is often left out of this “blend” are cultural and genetic influences from Africa, and hence the surprise expressed in the YouTube videos from DNA test result recipients. Not many people are aware that on average, Mexicans have 4% African blood in them, and less is known about African contributions to Mexican culture and history. When the topic of African influence in Mexico comes up, it is often mentioned that any sort of blackness has been “washed out” or has “blended in” to the national culture and gene pool, and historically, little attention has been given to it. As individuals and communities of people with predominately African heritage in Mexico make themselves more widely known to others, there has been a growing awareness of Africa’s continuing contribution to the nation of Mexico and the idea of “Mexicanness.”

There are three distinct infusions of “Africanness” into Mexico across the nation’s 500-year modern history. These infusions include the arrival of the first Africans as slaves during the colonial times, the arrival of African-Americans from the United States to the northern part of Mexico in the mid-19th Century, and African and Afro-Caribbean migration to Mexico in the age of globalism.

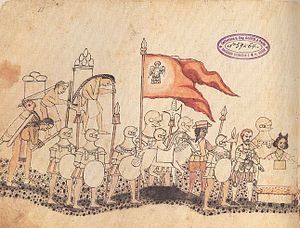

The first people of African origin in Mexico were those black slaves and freemen who accompanied and fought alongside the first Spanish conquistadors in the New World. It is estimated that 6 blacks took part in the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire. Notable among them was a freeman named Juan Garrido who was born in the Kongo Kingdom, traveled to Portugal as a boy and ended up in Santo Domingo in 1502 as one of the first colonists there. He joined Cortés on the march to the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlán and later joined conquistador Nuño de Guzmán on Spanish expeditions to what is now the Mexican states of Jalisco and Michoacán. Garrido is pictured in the Aztec book of history, the Codex Azcatitlan, as standing alongside Doña Marina, also known as the Malinche, the famous native translator and mistress of Cortés. Garrido later settled down in New Spain and married an Aztec woman and was listed in the colonial documents as a farmer of wheat. One of the first people to explore the northern modern-day Mexican state of Chihuahua and what is now known as the American Southwest was a man named Estevanico, who was part of the earlier Narváez expedition of Florida and the North American gulf coast. Estevanico was a slave and because of his prior experience with the natives of the northern part of Mexico, he was part of the Marcos de Niza expedition which left Mexico City to head north in 1539. As Estevanico was part of the scouting team traveling about a day ahead of de Niza, he was the first non-native American to visit Chihuahua and what is now the US states of New Mexico and Arizona. The first community of freed blacks in the Americas was founded in Mexico in 1608. In 1537 there was a small slave rebellion led by a man named Gaspar Yanga also called Nyanga in what is now the Mexican state of Veracruz. 40 years after the revolt, Spanish authorities recognized the former slaves’ right to exist as free men and the community of San Lorenzo de los Negros, today called Yanga, was given limited autonomy by the Spanish Crown.

The first people of African origin in Mexico were those black slaves and freemen who accompanied and fought alongside the first Spanish conquistadors in the New World. It is estimated that 6 blacks took part in the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire. Notable among them was a freeman named Juan Garrido who was born in the Kongo Kingdom, traveled to Portugal as a boy and ended up in Santo Domingo in 1502 as one of the first colonists there. He joined Cortés on the march to the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlán and later joined conquistador Nuño de Guzmán on Spanish expeditions to what is now the Mexican states of Jalisco and Michoacán. Garrido is pictured in the Aztec book of history, the Codex Azcatitlan, as standing alongside Doña Marina, also known as the Malinche, the famous native translator and mistress of Cortés. Garrido later settled down in New Spain and married an Aztec woman and was listed in the colonial documents as a farmer of wheat. One of the first people to explore the northern modern-day Mexican state of Chihuahua and what is now known as the American Southwest was a man named Estevanico, who was part of the earlier Narváez expedition of Florida and the North American gulf coast. Estevanico was a slave and because of his prior experience with the natives of the northern part of Mexico, he was part of the Marcos de Niza expedition which left Mexico City to head north in 1539. As Estevanico was part of the scouting team traveling about a day ahead of de Niza, he was the first non-native American to visit Chihuahua and what is now the US states of New Mexico and Arizona. The first community of freed blacks in the Americas was founded in Mexico in 1608. In 1537 there was a small slave rebellion led by a man named Gaspar Yanga also called Nyanga in what is now the Mexican state of Veracruz. 40 years after the revolt, Spanish authorities recognized the former slaves’ right to exist as free men and the community of San Lorenzo de los Negros, today called Yanga, was given limited autonomy by the Spanish Crown.

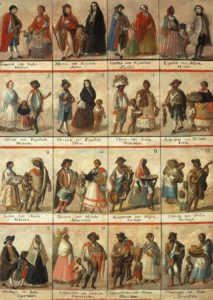

Famous examples aside, Africans began arriving in Mexico in great numbers as slaves in the early 1500s only a few decades after the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire. The native slave labor pool began to dwindle because of disease and by the fact that the indigenous were not used to the harsh working conditions imposed upon them by the Spanish. As the captive labor force diminished, King Charles the Fifth of Spain allowed slaves to be imported into the Spanish territories in the New World. Portugal had controlled the African slave trade in throughout most of the 16th Century and most slaves came from West Africa. Initially, African labor was brought to the plantations of the West Indies. Black slaves began arriving in greater numbers in Mexico starting in the 1580s, mostly to work the plantations in Mexico’s tropical areas, to work in the ever-growing silver mines and to be put to use in the textile industry. Sometimes slaves came directly from Africa, but also many came from the Caribbean territories. There were two main types of classifications for African slaves in colonial Mexico: Retintos and amulatados. The first group were swarthier and had a physical build for hard labor. The second group were of slighter build and sometimes with lighter skin and were generally used as house servants or to perform various menial tasks. In the 1500s and 1600s a slave usually cost around 400 pesos. Mexico never developed into a slave-based plantation society as the US South did, and by the 1640s the importation of African slaves had ceased. Mining had declined by this time and cheaper textiles began to be imported from England. Many Spanish slave owners in colonial Mexico had children with female slaves and those children became a new class of people collectively called mulato. In the colonial caste system, those with one black and one indigenous parent were called zambos. In general, black people were seen as “the other” in this period of Mexican history, something exotic and alien. In the records of the Spanish Inquisition in Mexico City there is an overrepresentation of people of African birth and African descent being tried for sexual dereliction and witchcraft. As many black people in this time period held on to vestiges of their African religious beliefs, there were quite a few people who were accused of being sorcerers and witches. There is even a famous legend of a woman known as La Mulata de Córdoba, which exists in Mexico to this day. A black woman who was jailed for practicing witchcraft in Veracruz asked her jailer for a piece of charcoal so she could pass the time drawing pictures in her jail cell. According to the legend, she drew a picture of a ship, recited a magical incantation and then jumped into the picture, thus escaping jail. During the colonial period it is unknown how many Africans and Afro-Caribbean people were imported to Mexico as slaves, but estimates reach as high as 200,000. As mentioned earlier, this importation pretty much ceased by the mid-1600s and the practice of slavery in Mexico, which was seen as somewhat anachronistic by the late 1700s was abolished by the new nation of Mexico in 1829.

Famous examples aside, Africans began arriving in Mexico in great numbers as slaves in the early 1500s only a few decades after the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire. The native slave labor pool began to dwindle because of disease and by the fact that the indigenous were not used to the harsh working conditions imposed upon them by the Spanish. As the captive labor force diminished, King Charles the Fifth of Spain allowed slaves to be imported into the Spanish territories in the New World. Portugal had controlled the African slave trade in throughout most of the 16th Century and most slaves came from West Africa. Initially, African labor was brought to the plantations of the West Indies. Black slaves began arriving in greater numbers in Mexico starting in the 1580s, mostly to work the plantations in Mexico’s tropical areas, to work in the ever-growing silver mines and to be put to use in the textile industry. Sometimes slaves came directly from Africa, but also many came from the Caribbean territories. There were two main types of classifications for African slaves in colonial Mexico: Retintos and amulatados. The first group were swarthier and had a physical build for hard labor. The second group were of slighter build and sometimes with lighter skin and were generally used as house servants or to perform various menial tasks. In the 1500s and 1600s a slave usually cost around 400 pesos. Mexico never developed into a slave-based plantation society as the US South did, and by the 1640s the importation of African slaves had ceased. Mining had declined by this time and cheaper textiles began to be imported from England. Many Spanish slave owners in colonial Mexico had children with female slaves and those children became a new class of people collectively called mulato. In the colonial caste system, those with one black and one indigenous parent were called zambos. In general, black people were seen as “the other” in this period of Mexican history, something exotic and alien. In the records of the Spanish Inquisition in Mexico City there is an overrepresentation of people of African birth and African descent being tried for sexual dereliction and witchcraft. As many black people in this time period held on to vestiges of their African religious beliefs, there were quite a few people who were accused of being sorcerers and witches. There is even a famous legend of a woman known as La Mulata de Córdoba, which exists in Mexico to this day. A black woman who was jailed for practicing witchcraft in Veracruz asked her jailer for a piece of charcoal so she could pass the time drawing pictures in her jail cell. According to the legend, she drew a picture of a ship, recited a magical incantation and then jumped into the picture, thus escaping jail. During the colonial period it is unknown how many Africans and Afro-Caribbean people were imported to Mexico as slaves, but estimates reach as high as 200,000. As mentioned earlier, this importation pretty much ceased by the mid-1600s and the practice of slavery in Mexico, which was seen as somewhat anachronistic by the late 1700s was abolished by the new nation of Mexico in 1829.

A second migration to Mexico of people of African descent began almost immediately after the country achieved its independence. As Mexico outlawed slavery in 1829, escaping to Mexico became an objective of many enslaved African-Americans wishing to flee “the peculiar institution.” The trickle across the Rio Grande grew larger with time. Many Americans are unaware that a branch of the Underground Railroad went south instead of north, thus funneling hundreds of escaped slaves into the northern part of Mexico. A famous group of blacks called the Mascogos, comprised of escaped slaves and freemen, numbering into the hundreds, left the plantations of Florida and made the dangerous overland journey crossing several southern states, eventually making it to northern Mexico, settling in the town of El Nacimiento in the state of Coahuila. Their descendants live in that town to this day. Besides the Mascogos group, runaway slaves tended not to arrive to Mexico in groups or even in family units. As a result of this, many American blacks just intermarried and silently “blended in” to mainstream Mexican culture retaining little of what they left behind in the United States, especially after a few generations.

The third wave of African people and people of African descent coming to Mexico has occurred in the age of globalization over the past 50 years. This is primarily because of the ease of migration. Many people of African descent fled Caribbean island nations and territories since the 1960s to escape communism, poverty or natural disasters, and many ended up in Mexico. Although not a country known for taking in mass numbers of African refugees, Mexico has harbored some people escaping brutal conditions in Africa. With ease of travel in the modern age African and African-descendants from outside the mother continent have ended up in Mexico for a variety of reasons. A notable Afro-Mexican from the “age of globalization” group is the only Mexican woman ever to have won an Academy Award. Lupita Nyong’o won an Oscar for best supporting actress for her role in the movie “Twelve Years a Slave.” Named for the Virgin of Guadalupe, Nyong’o was born of Kenyan parents in Mexico City in 1983. She moved to Kenya as a small child but returned to Mexico at the age of 16, living in Taxco, Guerrero. She retains dual Mexican and Kenyan citizenship and is fluent in Spanish, English, the language of her Kenyan family called Luo and the East African lingua franca, Swahili. As the people from this third wave have not arrived in large groups, there are no neighborhoods or specific areas of the country in which Africans have congregated. There is no expat African barrio in Mexico City, for example. It is often assumed even by the Mexicans themselves when a black person is spotted in a major city that the person is a recent arrival or guest worker from Africa, the US or the Caribbean.

The third wave of African people and people of African descent coming to Mexico has occurred in the age of globalization over the past 50 years. This is primarily because of the ease of migration. Many people of African descent fled Caribbean island nations and territories since the 1960s to escape communism, poverty or natural disasters, and many ended up in Mexico. Although not a country known for taking in mass numbers of African refugees, Mexico has harbored some people escaping brutal conditions in Africa. With ease of travel in the modern age African and African-descendants from outside the mother continent have ended up in Mexico for a variety of reasons. A notable Afro-Mexican from the “age of globalization” group is the only Mexican woman ever to have won an Academy Award. Lupita Nyong’o won an Oscar for best supporting actress for her role in the movie “Twelve Years a Slave.” Named for the Virgin of Guadalupe, Nyong’o was born of Kenyan parents in Mexico City in 1983. She moved to Kenya as a small child but returned to Mexico at the age of 16, living in Taxco, Guerrero. She retains dual Mexican and Kenyan citizenship and is fluent in Spanish, English, the language of her Kenyan family called Luo and the East African lingua franca, Swahili. As the people from this third wave have not arrived in large groups, there are no neighborhoods or specific areas of the country in which Africans have congregated. There is no expat African barrio in Mexico City, for example. It is often assumed even by the Mexicans themselves when a black person is spotted in a major city that the person is a recent arrival or guest worker from Africa, the US or the Caribbean.

Unknown to many modern-day Mexicans, many descendants from the first colonial wave of Africans continue to live in intact black communities in parts of the former plantation areas of Veracruz and in the Pacific coastal areas of Guerrero and Oaxaca. The latter Pacific area is known as the Costa Chica, or “Small Coast” in English. There has been no mass migration out of these areas to major Mexican cities. While African DNA is evident in the people inhabiting the small towns of these locations, the old African culture has been preserved only in small pieces in things like food, music, dance and clothing.

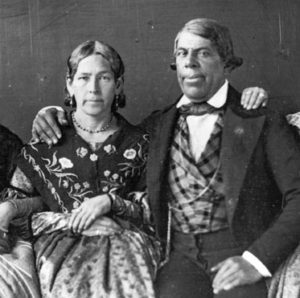

Outside these mostly remote areas where people of high percentage of African heritage currently live, what influence has historic “Africanness” had on Mexican national culture? One of Mexico’s iconic dishes and one found on the menu in many Mexican restaurants in the United States, mole poblano, has its origins in African cooking, as do many other peanut-based dishes from Veracruz. Various recipes involving plantains also come from Mexico’s African heritage. When non-Mexicans ask Mexicans about the origins of the popular song, “La Bamba,” the average Mexican will be unable to explain that the title of the song, the rhythm and the dancing that goes along with it has deep African roots. Other bits of popular culture with black influence include the character from the Mexican bingo game Lotería called “El Negrito” and a series of comic books dating back to the 1940s about a mischievous black boy named Memín Pinguín. Some historical figures with mixed mestizo and African heritage in Mexico include Mexican president Vicente Guerrero, Mexican War of Independence hero José María Morelos and the last governor of California under Mexican rule, Pio Pico.

Outside these mostly remote areas where people of high percentage of African heritage currently live, what influence has historic “Africanness” had on Mexican national culture? One of Mexico’s iconic dishes and one found on the menu in many Mexican restaurants in the United States, mole poblano, has its origins in African cooking, as do many other peanut-based dishes from Veracruz. Various recipes involving plantains also come from Mexico’s African heritage. When non-Mexicans ask Mexicans about the origins of the popular song, “La Bamba,” the average Mexican will be unable to explain that the title of the song, the rhythm and the dancing that goes along with it has deep African roots. Other bits of popular culture with black influence include the character from the Mexican bingo game Lotería called “El Negrito” and a series of comic books dating back to the 1940s about a mischievous black boy named Memín Pinguín. Some historical figures with mixed mestizo and African heritage in Mexico include Mexican president Vicente Guerrero, Mexican War of Independence hero José María Morelos and the last governor of California under Mexican rule, Pio Pico.

In an attempt to recognize and quantify modern-day people of African identity in Mexico, in 2015 the Mexican government conducted what was called an “intercensal survey” of its people to identify those citizens who considered themselves to be Afro-Mexicans. There were 1,381,853 people who identified as belonging to this group, which makes up 1.2% of the country’s population. Lauded by civil rights groups and social activists, this was the first time in Mexican history that the government formally reached out to acknowledge Mexicans of African descent. In the 2020 census, the term “Afro-Mexican” will be a formal racial and ethnic category. A full 500 years after the Spanish Conquest of Mexico, the descendants of Mexico’s first African settlers will finally get the formal recognition they have long deserved.

REFERENCES

Arce, Christine. México’s Nobodies: The Cultural Legacy of the Soldadera and Afro-Mexican Women. Albany: SUNY Press, 2016.

Archibold, Ronald C. “Negro? Prieto? Moreno? A question of Identity for Black Mexicans.” New York Times, 25 Oct. 2014.

4 thoughts on “Afro-Mexicans, a Hidden Heritage”

My name is Michael Orlando Zaragoza Gutierrez. I am the son of an Unknown, Bronze Star Recipient for Bravery and Selfless actions in the face of the Enemy. My Father, Cpl. Marcos G. Zaragoza, US Army, Decorated American Hero of WWII, Battle of Guadalcanal. Corporal Zaragoza was amongst the forces of the US Army, tasked with extricating the embattled US Marines. Yes Army in Guadalcanal, not Marine, not too many people know this. The US Army was tasked to relieve the embattled US Marine forces off of The Fetid Island of Death called Guadalcanal! The brave US Marines had been engaged in constant battle for almost 6 six months, against The Indomitable and up to then undefeated Army of Imperial Japan. I am the last survivor and privileged retainer of this knowledge and if You would like to know more about this please contact me. I am 68 years old and when I am gone this wonderful Mexican Story/ History will be gone with me. I\’ve been trying to tell my father\’s story for a long time to no avail, no one seems to care about our Own Mexican American Mestizo Heroes! It\’s my heritage, it is YOUR Heritage!

I am a second generation Natural Born, United States of America Citizen. I had the privilege of being born in Los Angeles, California and from the age of 6 six months until I was 14 years old, I lived in a self sustaining rural Farm/Ranch in what is now the bustling city of Tijuana, Baja California, Mexico. While I was growing up and going to school in Mexico, I was never referred to as a Mexican American, no, there in Mexico I was just another Mexican. Yet as soon as I started going to High School in California, I was classified as a Mexican American or Chicano or wet back!

Mexico should be known as The Melting Pot of the Americas and not the United States. The US of A, is the melting pot for European people and not as it is touted, as the melting pot of the world, Not so, the famous \”Melting Pot\”, does it not translate into \”Mestizaje\”, the mixture of bloods? In Mexico, people of African descent are not persecuted as in the US of A, why? because they\’re Mexican! Not African Mexicans, just Mexicans! Thank God my Mexican People are intimately inclusive of All other Races. I did my DNA test and was I ever \”not really surprised\”, my father and uncles always seemed Moroccan, Libyan, Arabic to me. I am 41 %, European, Iberian Peninsula, Aragon and Castilla (La Mancha), 34%, North American Native, Purepecha/Tarasco, Michoacan, Mexico and 21%, West African, Fulani, Mandinka and Bantu. 3% Asian/Pacific Islander, 1% other.

Michaelrowcliff Glenn

Mexicans Irish German native Americans Aztec Americans

Comanche Cheyenne Navajo Chippewa chickenlsaw Shawnee’s

this is the information i was looking for. thanks foe a well written article.

Thank you for stopping by!