Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

The year was 1848. Maya rebel leader Jose Maria Barrera, who had been driven from his ancestral village by refreshed Mexican army forces, led a small group of revolutionaries to a small cenote in a dense and uninhabited jungle area in the southeastern part of the Yucatán. The cenote, which is a type of natural well sacred to the Maya, was named Lom Ha, which means, in English, “cleft spring.” At the base of a large mahogany tree near an entrance to a cave near the cenote, Barrera found a curious object: a wooden cross that appeared to emanate sounds. The cross looked somewhat like a Christian cross and also somewhat like the ancient Maya tree of life, a sacred symbol going back thousands of years. To the Maya people with Barrera the cross was a very special find. Not only did it seem to talk like so many inanimate objects connected with the spirit world in times past, it was also found near two sacred places: the sacred well, the cenote; and a cave, the symbolic entrance to the underworld. Word soon spread throughout the area of this miraculous find and a within a few months a small shrine was built near the cenote to house this mysterious object. As more and more people began to hear of this cross and believe in it, a new religion was born.

The year was 1848. Maya rebel leader Jose Maria Barrera, who had been driven from his ancestral village by refreshed Mexican army forces, led a small group of revolutionaries to a small cenote in a dense and uninhabited jungle area in the southeastern part of the Yucatán. The cenote, which is a type of natural well sacred to the Maya, was named Lom Ha, which means, in English, “cleft spring.” At the base of a large mahogany tree near an entrance to a cave near the cenote, Barrera found a curious object: a wooden cross that appeared to emanate sounds. The cross looked somewhat like a Christian cross and also somewhat like the ancient Maya tree of life, a sacred symbol going back thousands of years. To the Maya people with Barrera the cross was a very special find. Not only did it seem to talk like so many inanimate objects connected with the spirit world in times past, it was also found near two sacred places: the sacred well, the cenote; and a cave, the symbolic entrance to the underworld. Word soon spread throughout the area of this miraculous find and a within a few months a small shrine was built near the cenote to house this mysterious object. As more and more people began to hear of this cross and believe in it, a new religion was born.

So who were these rebels and why were they in the middle of the jungle? What set the stage for the appearance of this talking cross? The Yucatán Peninsula was always difficult to govern from the central seat of authority in Mexico City. From the times of colonial New Spain, the people of the Yucatán were left pretty much undisturbed by the political machinations coming from the capital city. Society in the Yucatán evolved on its own and became highly stratified over time. The native Maya were left alone, for the most part, living traditional lives on communal lands. The Maya interaction with mainstream Hispanic-Mexican society in the late colonial period and in the early days of the independent nation of Mexico was somewhat limited. In the 1830s the relation between the Maya and the non-Maya in the Yucatán began to change. The 1830s saw the rise of the demand for henequen, a fiber used in the making of rope and twine, which is derived from a type of agave plant. Henequen plantations popped up all over the Yucatán, and encroachment onto Mayan communal lands were common. The local Maya worked almost as slaves on the plantations, had very little rights and no way to redress their grievances. The elite plantation class became very wealthy and powerful and by the early 1840s they saw very little need for the central authority in Mexico City which provided little help with the minor uprisings and local skirmishes instigated by the  disgruntled Maya. By 1841, after seeing the success of another breakaway Mexican province now called the Republic of Texas, the people in charge of everyday affairs in the Yucatán decided to go their own way and declare their independence from Mexico as the Republic of Yucatán. Even though the constitution of this new nation was praised for its progressivism, the young republic was off to a rocky start and internal turmoil flared up as soon as the new red, green and white flag was hoisted over the capital city of Mérida. The new Republic of Yucatán had a hard time pacifying the Maya rebels who were growing in number and becoming more organized. By the end of the 1840s the Republic of Yucatán could not handle what was amounting to an all-out internal civil war. The nation’s president, Santiago Méndez, became increasingly desperate as the Maya rebels’ attacks grew more frequent and more severe. He appealed to the nations of Spain, Great Britain and the United States for help, even promising to cede the Yucatán’s complete sovereignty and become a colony or possession of a foreign power in exchange for military assistance. The Yucatán delegation in Washington DC got serious consideration from American president James K. Polk and the US House of Representatives actually passed what was called “The Yucatán Bill” to green-light American annexation of the peninsula. The bill was shot down in the US Senate because that legislative body had deemed that the Mexican War, which had not yet ended, was already too costly. With the Spanish, British and Americans rejecting him, President Méndez made a final appeal to Mexico City. In August of 1848, 6 months after Mexico’s war with the United States had ended, the Yucatán was brought back into the fold of Mexico. The Mexican government then sent troops and arms to help the Hispanic Yucatecos put down the fragmented Maya rebellion, which would later be called The Caste War. The Maya had been pushed into the densely forested area of the southeast Yucatán where no significant towns or villages existed. It was only months after the federal government sent in its military resources to quash the rebellion that the “talking cross” appeared to José María Barrera and his weary band of fighters in the jungle.

disgruntled Maya. By 1841, after seeing the success of another breakaway Mexican province now called the Republic of Texas, the people in charge of everyday affairs in the Yucatán decided to go their own way and declare their independence from Mexico as the Republic of Yucatán. Even though the constitution of this new nation was praised for its progressivism, the young republic was off to a rocky start and internal turmoil flared up as soon as the new red, green and white flag was hoisted over the capital city of Mérida. The new Republic of Yucatán had a hard time pacifying the Maya rebels who were growing in number and becoming more organized. By the end of the 1840s the Republic of Yucatán could not handle what was amounting to an all-out internal civil war. The nation’s president, Santiago Méndez, became increasingly desperate as the Maya rebels’ attacks grew more frequent and more severe. He appealed to the nations of Spain, Great Britain and the United States for help, even promising to cede the Yucatán’s complete sovereignty and become a colony or possession of a foreign power in exchange for military assistance. The Yucatán delegation in Washington DC got serious consideration from American president James K. Polk and the US House of Representatives actually passed what was called “The Yucatán Bill” to green-light American annexation of the peninsula. The bill was shot down in the US Senate because that legislative body had deemed that the Mexican War, which had not yet ended, was already too costly. With the Spanish, British and Americans rejecting him, President Méndez made a final appeal to Mexico City. In August of 1848, 6 months after Mexico’s war with the United States had ended, the Yucatán was brought back into the fold of Mexico. The Mexican government then sent troops and arms to help the Hispanic Yucatecos put down the fragmented Maya rebellion, which would later be called The Caste War. The Maya had been pushed into the densely forested area of the southeast Yucatán where no significant towns or villages existed. It was only months after the federal government sent in its military resources to quash the rebellion that the “talking cross” appeared to José María Barrera and his weary band of fighters in the jungle.

By 1850 the cross had garnered a massive following and served to unite the rebelling Maya under a new religion and political system which blended Christianity with the old Maya beliefs which had been suppressed for 350 years. The holy place of pilgrimage where the cross appeared was called Chan Santa Cruz, which meant, in a combination of Maya and Spanish, “Little Holy Cross.” Chan Santa Cruz eventually became the de facto name of the Maya political entity that grew out of the Maya-occupied lands of the Yucatán Peninsula which included about 80% of the modern-day Mexican state of Quintana Roo, small areas of the modern-day Mexican states of Yucatán and Campeche, and a small part of the modern-day nation of Belize. By the end of 1850, a larger shrine had been built to the Talking Cross and a larger cross was installed in it. The shrine was located at a place called X-Balam-Nah, which means, in English, “The Little House of the Jaguar.” Followers became known as cruzobs and the new religion is often referred to the Cruzob faith.

By 1850 the cross had garnered a massive following and served to unite the rebelling Maya under a new religion and political system which blended Christianity with the old Maya beliefs which had been suppressed for 350 years. The holy place of pilgrimage where the cross appeared was called Chan Santa Cruz, which meant, in a combination of Maya and Spanish, “Little Holy Cross.” Chan Santa Cruz eventually became the de facto name of the Maya political entity that grew out of the Maya-occupied lands of the Yucatán Peninsula which included about 80% of the modern-day Mexican state of Quintana Roo, small areas of the modern-day Mexican states of Yucatán and Campeche, and a small part of the modern-day nation of Belize. By the end of 1850, a larger shrine had been built to the Talking Cross and a larger cross was installed in it. The shrine was located at a place called X-Balam-Nah, which means, in English, “The Little House of the Jaguar.” Followers became known as cruzobs and the new religion is often referred to the Cruzob faith.

From the time of its discovery, the cross, and its designated replacement, had literally talked. People in its presence heard one voice and one message, spoken in the local Maya dialect. The message of the cross usually had two themes: God’s love and resistance. The messages were transcribed and circulated throughout both the Mexican-controlled and Maya-controlled parts of the Yucatán Peninsula, always ending with the signature “Juan de la Cruz” which was a pseudonym for the talking cross religion’s first priest. Scholars suspect that Juan de la Cruz could have been Atanasio Puc, one of the leaders of the Maya rebel movement under the command of José María Barrera, others believe that it could have been a man known as Manuel Nahuat, a close associate of the rebel commanders. Historians have also accused Nahuat of being a ventriloquist and the one responsible for the cross to have a “voice.” Whether the cross did give divine messages and prophesy or if it was an elaborate hoax is of little importance in light of what the cross did for the movement of Maya resistance. The appearance of the cross was responsible for a renaissance of Maya culture, it was the impetus for socio-political unification and it served as a symbol of hope for the Maya people.

The belief in the talking cross was so powerful that even in the face of “bad prophesy,” the Maya soldiered on, continued to believe and continued to fight. For example, one of the cross’ spoken mandates was for the Maya to attack the Mexican army base at Kampocolché. The attack took place on January 4, 1851. Many of the Maya believed that the Talking Cross would make them impervious to enemy bullets. The Maya attack force was badly defeated. The Mexican army then heard about the shrine, took away the cross and killed the alleged ventriloquist, Manuel Nahuat. A new cross appeared and other similar crosses popped up in other parts of the Maya-occupied territory. The faith in the new religion only grew stronger with time.

The belief in the talking cross was so powerful that even in the face of “bad prophesy,” the Maya soldiered on, continued to believe and continued to fight. For example, one of the cross’ spoken mandates was for the Maya to attack the Mexican army base at Kampocolché. The attack took place on January 4, 1851. Many of the Maya believed that the Talking Cross would make them impervious to enemy bullets. The Maya attack force was badly defeated. The Mexican army then heard about the shrine, took away the cross and killed the alleged ventriloquist, Manuel Nahuat. A new cross appeared and other similar crosses popped up in other parts of the Maya-occupied territory. The faith in the new religion only grew stronger with time.

In spite of the attack on the Talking Cross shrine, not only did the faith in the new religion increase, the sense of unity did too, and many Maya from all over the Yucatán Peninsula and from places as far away as Guatemala and Honduras came to the rebel heartland to participate in the new society that grew up alongside the religion. Because the new Maya state bordered on the colony of British Honduras to the south, the British government entered into treaties and trade agreements with the new Maya nation of Chan Santa Cruz, thus recognizing it as a sovereign state. This happened in the late 1850s. As part of the trade with the British, the Maya nation received much needed modern armaments with which to fight the Mexican national forces which were desperate to retake all of the Maya land to incorporate it back into Mexico.

Historians may argue that the religion that the Talking Cross inspired was more powerful than any modern weaponry the British could supply. What was nicknamed “The Maya Church” grew strong and formalized its clergy and belief systems. Infusing Christianity with ancient Maya beliefs, central to the new faith was the Talking Cross itself, which was seen as a direct connection with God who had several native names including K’u, Hunab K’u and Hahab K’u. Below God were the angels, referred to as Chakoob. In the Cruzob pantheon were also lesser gods or elemental spirits. Among them was Kiichpam Kolel, or the “beautiful grandmother” who was associated with the earth and all in the universe that was feminine, and was represented by the image of Our Lady of Guadalupe, the Mexican apparition of the Virgin Mary. The Yumsiloob were a collection of ancestral spirits that could be petitioned by the living for help. The Talking Cross pantheon also included a collection of Ik’oob, a group of autonomous spirits that could be prayed to for a variety of reasons and loosely corresponded to Catholic saints. The spirits known for evil, which must be cleared out of an area before a sacred ritual can be performed, were called K’asal Ik’oob. A small representation of the Talking Cross in the home was called an Ix Ceel and was usually incorporated into a family shrine. The new religion had two annual festivals that directly corresponded to the annual festivals of the ancient Maya. One was called the The Day of the Cross and the other The Day of the Grandmother. The new religion had a pope, a supreme infallible religious leader, called an Ahau Kan, which translates to English as “Lord Wisdom.” The first Ahau Kan of this new religion was Manuel Nahuat who served until his capture and death in 1851. With the Maya pope came a whole religious hierarchy including cardinals, archbishops, bishops and priests, all with corresponding Maya names. The clergy was responsible for all church matters from marriages to exorcisms. As an interesting footnote, not all of the people holding title of Ahau Kan, or Maya pope were men. In 1871, for example, the head of the church and main interpreter of the messages of the Talking Cross was a woman named María Uicab.

Historians may argue that the religion that the Talking Cross inspired was more powerful than any modern weaponry the British could supply. What was nicknamed “The Maya Church” grew strong and formalized its clergy and belief systems. Infusing Christianity with ancient Maya beliefs, central to the new faith was the Talking Cross itself, which was seen as a direct connection with God who had several native names including K’u, Hunab K’u and Hahab K’u. Below God were the angels, referred to as Chakoob. In the Cruzob pantheon were also lesser gods or elemental spirits. Among them was Kiichpam Kolel, or the “beautiful grandmother” who was associated with the earth and all in the universe that was feminine, and was represented by the image of Our Lady of Guadalupe, the Mexican apparition of the Virgin Mary. The Yumsiloob were a collection of ancestral spirits that could be petitioned by the living for help. The Talking Cross pantheon also included a collection of Ik’oob, a group of autonomous spirits that could be prayed to for a variety of reasons and loosely corresponded to Catholic saints. The spirits known for evil, which must be cleared out of an area before a sacred ritual can be performed, were called K’asal Ik’oob. A small representation of the Talking Cross in the home was called an Ix Ceel and was usually incorporated into a family shrine. The new religion had two annual festivals that directly corresponded to the annual festivals of the ancient Maya. One was called the The Day of the Cross and the other The Day of the Grandmother. The new religion had a pope, a supreme infallible religious leader, called an Ahau Kan, which translates to English as “Lord Wisdom.” The first Ahau Kan of this new religion was Manuel Nahuat who served until his capture and death in 1851. With the Maya pope came a whole religious hierarchy including cardinals, archbishops, bishops and priests, all with corresponding Maya names. The clergy was responsible for all church matters from marriages to exorcisms. As an interesting footnote, not all of the people holding title of Ahau Kan, or Maya pope were men. In 1871, for example, the head of the church and main interpreter of the messages of the Talking Cross was a woman named María Uicab.

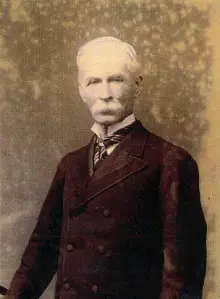

As with many indigenous resistance movements and attempts at sovereign states, the independent Maya state of Chan Santa Cruz could not last. It had a good run for almost 50 years – the span of 2 generations – but pressures from the outside eventually sealed the fate of the new Maya nation. The British, who had long had treaties and trade agreements with the Maya state of Chan Santa Cruz, were under increasing pressure to support and trade with the Mexican government headed by Porfirio Diaz who had brought stability to Mexico during his 30-year reign. The British Empire had long had an uneasy relationship with the nation of Mexico, from the early days of Mexico’s independence and British designs on the province of California, through the times of the French occupation of Mexico. The Porfirio Diaz regime, which was becoming friendly to British business interests, had much to offer in trade and potential commerce. For the British to have full friendly relations with Mexico, they knew they had to give up their treaties with the small Maya state in the Yucatán. In 1893, London sent Sir Spenser Buckingham St. John to Mexico City to disentangle Her Majesty’s Government from the Maya state and help Mexico regain complete control of the Yucatán once and for all. The 68-year-old Sir Spenser, a Knight Grand Cross of the Order of St. Michael and St. George, who had spent his whole life in service of the British Empire, drafted and served up the Spenser-Mariscal Treaty. This treaty ended British support and recognition of the Maya state and helped the Mexicans regain territory that had been the sovereign domain of a stable indigenous nation for almost half a century. Within a few years, all Maya-occupied territories in the Yucatán were overtaken by Mexican forces.

As with many indigenous resistance movements and attempts at sovereign states, the independent Maya state of Chan Santa Cruz could not last. It had a good run for almost 50 years – the span of 2 generations – but pressures from the outside eventually sealed the fate of the new Maya nation. The British, who had long had treaties and trade agreements with the Maya state of Chan Santa Cruz, were under increasing pressure to support and trade with the Mexican government headed by Porfirio Diaz who had brought stability to Mexico during his 30-year reign. The British Empire had long had an uneasy relationship with the nation of Mexico, from the early days of Mexico’s independence and British designs on the province of California, through the times of the French occupation of Mexico. The Porfirio Diaz regime, which was becoming friendly to British business interests, had much to offer in trade and potential commerce. For the British to have full friendly relations with Mexico, they knew they had to give up their treaties with the small Maya state in the Yucatán. In 1893, London sent Sir Spenser Buckingham St. John to Mexico City to disentangle Her Majesty’s Government from the Maya state and help Mexico regain complete control of the Yucatán once and for all. The 68-year-old Sir Spenser, a Knight Grand Cross of the Order of St. Michael and St. George, who had spent his whole life in service of the British Empire, drafted and served up the Spenser-Mariscal Treaty. This treaty ended British support and recognition of the Maya state and helped the Mexicans regain territory that had been the sovereign domain of a stable indigenous nation for almost half a century. Within a few years, all Maya-occupied territories in the Yucatán were overtaken by Mexican forces.

And with the end of the Maya state, the great Talking Cross withered and died.

REFERENCES (This is not a formal bibliography)

The Caste War of Yucatan by Nelson Reed

Various online sources