Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

The East Germans and the Italians dominated the opening round of rowing in the men’s coxed pairs at the 1968 Mexico City Olympics. The East Germans had promise, but in the finals the Italians crossed the finish line almost 2 full seconds ahead of their closest rivals, the team from the Netherlands that would earn the silver medal for this event. The East Germans lost to the team from Denmark which beat them by a mere fifteen hundredths of a second to earn the bronze medal. These Olympic rowing events took place between October 13 and October 19, 1968 at the Virgilio Uribe Olympic Course in the Canal de Cuemanco. The canal is located in the remnants of Lake Xochimilco in the southern part of Mexico’s Federal District and part of the greater Mexico City metropolitan area. While most of the nation of Mexico was overjoyed to be hosting the Olympic Games in 1968, many of the residents of Xochimilco were not. To create the Olympic Rowing Course in the canals of Xochimilco, the Mexican government first had to destroy several square acres of chinampas, or what has been termed “floating gardens.” Some anthropologists believe that the Xochimilco locals have been tending these chinampas for several hundred years with individual family histories involving chinampa farming going back too many generations to count. So, while most of the nation of Mexico cheered, the chinampa farmers of Xochimilco wept. The acquatic course is still in use today by canoers, kayakers, and rowers. The destroyed floating gardens were never restored.

The East Germans and the Italians dominated the opening round of rowing in the men’s coxed pairs at the 1968 Mexico City Olympics. The East Germans had promise, but in the finals the Italians crossed the finish line almost 2 full seconds ahead of their closest rivals, the team from the Netherlands that would earn the silver medal for this event. The East Germans lost to the team from Denmark which beat them by a mere fifteen hundredths of a second to earn the bronze medal. These Olympic rowing events took place between October 13 and October 19, 1968 at the Virgilio Uribe Olympic Course in the Canal de Cuemanco. The canal is located in the remnants of Lake Xochimilco in the southern part of Mexico’s Federal District and part of the greater Mexico City metropolitan area. While most of the nation of Mexico was overjoyed to be hosting the Olympic Games in 1968, many of the residents of Xochimilco were not. To create the Olympic Rowing Course in the canals of Xochimilco, the Mexican government first had to destroy several square acres of chinampas, or what has been termed “floating gardens.” Some anthropologists believe that the Xochimilco locals have been tending these chinampas for several hundred years with individual family histories involving chinampa farming going back too many generations to count. So, while most of the nation of Mexico cheered, the chinampa farmers of Xochimilco wept. The acquatic course is still in use today by canoers, kayakers, and rowers. The destroyed floating gardens were never restored.

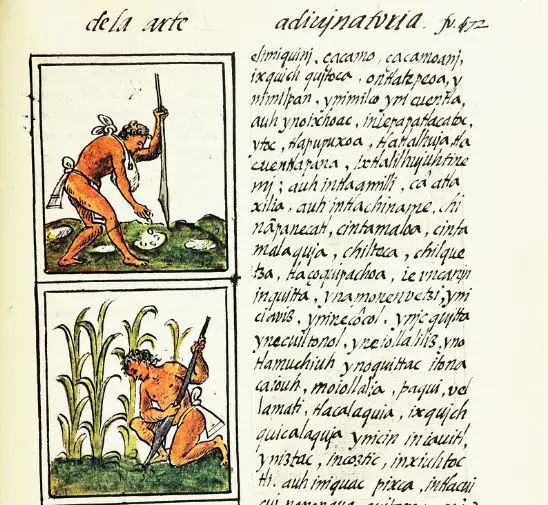

The term “floating garden” is somewhat fanciful and romantic and doesn’t really describe what a chinampa actually is. Chinampas don’t float, rather, they are raised square or rectangular plots of land used for farming in shallow lakes. A chinampa field is essentially a series of artificial islands connected by a series of canals. How are these created? The chinampa farmer builds up the chinampa by first making a small fence-like structure and attaching it to a series of stakes placed in a square or rectangular formation in the lake bottom. This underwater fenced-in area is filled by dredging the bottom of the lake. Eventually, an island forms above the water level of the lake as the farmer piles more and more mud and debris into the center of the fenced-in area. Sometimes farmers plant types of cypress or willow trees in each of the 4 corners of the chinampa to secure the underwater fence. Because the sediment and decaying vegetation at the bottom of the lake is rich in nutrients, the chinampa becomes a very fertile place for growing crops. Periodically, chinampa farmers clear sediment and debris out the canals and pile it on top of the chinampa thus ensuring successive productive growing seasons by introducing fresh nutrient-rich materials. The Aztecs called chinampas chinamitl which means, “square made of sticks.” Chinampas were measured in mati, with one mati equaling 1.667 meters. Using Aztec codexes and some colonial documents as guides, archaeologists and other researchers theorize that most Aztec chinampas measured roughly 100 feet by 10 feet. Sometimes they had small ditches running down the middle of them to ensure that all the plants in the chinampa had access to water, especially during times of low rainfall or drought. Generally, a chinampa farmer could take in seven harvests per year and grow a variety of crops on these fertile artificial islands.

Bernal Díaz del Castillo, a conquistador under the command of Hernán Cortés during the conquest of the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlán, was the first European to describe chinampas. As the Spaniards were the invited guests of Aztec Emperor Montezuma and lived among the Aztecs for months before things went sour, Bernal Díaz had ample time to observe and write. His diaries and notes eventually became his great work, Historia de la verdadera conquista de la Nueva España, or in English, The True History of the Conquest of New Spain. Bernal Díaz describes the chinampas the Spanish first encountered in Xochimilco, which in the Nahuatl language of the Aztecs appropriately means, “Fields of Flowers.” Ironically, Bernal Díaz was describing the exact same location used for the 1968 Olympic rowing events. Here are his words:

Bernal Díaz del Castillo, a conquistador under the command of Hernán Cortés during the conquest of the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlán, was the first European to describe chinampas. As the Spaniards were the invited guests of Aztec Emperor Montezuma and lived among the Aztecs for months before things went sour, Bernal Díaz had ample time to observe and write. His diaries and notes eventually became his great work, Historia de la verdadera conquista de la Nueva España, or in English, The True History of the Conquest of New Spain. Bernal Díaz describes the chinampas the Spanish first encountered in Xochimilco, which in the Nahuatl language of the Aztecs appropriately means, “Fields of Flowers.” Ironically, Bernal Díaz was describing the exact same location used for the 1968 Olympic rowing events. Here are his words:

“The chinampas were formed by heaping up the soft mud from the lake onto the woven reeds in order to form seed beds for flowers and vegetables, and these floating gardens gradually increased in size and became more compact from the growth of the interlacing roots of the willows and other water-loving plants until they may have supported a small hut for the owner and his family, and the lengthening roots eventually anchored then on the shallow margin of the lake.

These gardens are divided into long narrow strips with canals running between just wide enough for the passage of a dugout canoe. The Indian cultivator poles his canoe along the narrow channels and scoops up the soft mud from the bottom to spread it over the land and splashes the water over the growing plants with his paddle. It was probably this method of cultivation which gave the mainly rectangular arrangement of the streets of the city of Tenochtitlán, the more unsymmetrical canals showing the original waterways between the mudbanks, while the aggregation of chinampas may have left an irregular margin of outlying houses and gardens.”

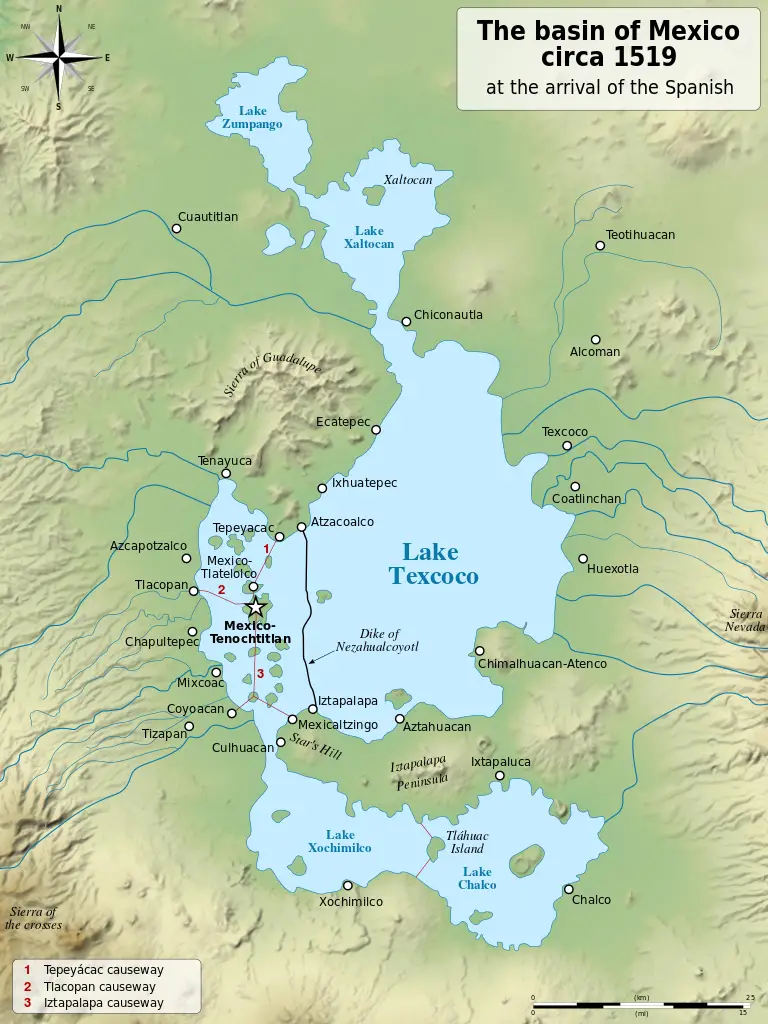

Bernal Díaz further described how the Aztecs divided the lake for the benefit of chinampa farming. There were 5 lakes in one, essentially, with Lake Texcoco having what could be considered bays that were deemed to be separate lakes. Lake Zumpango and Lake Xaltocan were the northern arms of Lake Texcoco while Lake Chalco and Lake Xochimilco were the southern arms. The Aztecs built their capital on an island in the southeastern part of Lake Texcoco near where Lake Chalco and Lake Xochimilco blended in with the larger body of the lake. The waters of Lakes Chalco and Xochimilco were fresher than most of the rest of the Lake Texcoco system, so Aztec engineers built a dyke crossing the middle of the southwestern part of Lake Texcoco to keep most of the farming-friendly fresh water in a more concentrated form in the southern zone of the lake system. This left a large part Lake Texcoco not suitable for chinampa-based farming. The wealthy Kingdom of Texcoco on the eastern shores of the lake with the same name had no chinampas owing to the brackish and swampy nature of their portion of the lake. The small kingdom that would later be incorporated into the Aztec Empire often worked with the Tenochtitlán Aztecs on shared water issues including cooperating during times of flood. For more information on the Kingdom of Texcoco please see Mexico Unexplained episode number 133: https://mexicounexplained.com//the-tragic-history-of-the-house-of-texcoco/. At the time of the Spanish arrival the island city of Xaltocan in the northern section of the Lake Texcoco system had chinampas surrounding it because the water there was a little less salty than the waters immediately to the south, but the bulk of the chinampas were in that cordoned off southwest part of the lake system. The Spanish noted that the island city of Tenochtitlán had probably grown over the years because of chinampa farming ringing the island. The canals of the older chinampas closer to the island’s shores were gradually filled in thus giving the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlán more room to expand. The bulk of the chinampas in the lake area existed in Xochimilco and Chalco where people grew corn, squash, beans, amaranth, tomatoes, peppers, flowers, and herbs. The chinampas around Tenochtitlán grew these traditional crops as well, but also grew fruits and vegetables from other parts of the empire. The Spanish marveled at the variety of the plants growing in the chinampas surrounding the imperial capital. The Spanish also wrote that chinampas were passed down through families in wills and many families had been tending to the same group of chinampas for 6 or 7 generations.

Bernal Díaz further described how the Aztecs divided the lake for the benefit of chinampa farming. There were 5 lakes in one, essentially, with Lake Texcoco having what could be considered bays that were deemed to be separate lakes. Lake Zumpango and Lake Xaltocan were the northern arms of Lake Texcoco while Lake Chalco and Lake Xochimilco were the southern arms. The Aztecs built their capital on an island in the southeastern part of Lake Texcoco near where Lake Chalco and Lake Xochimilco blended in with the larger body of the lake. The waters of Lakes Chalco and Xochimilco were fresher than most of the rest of the Lake Texcoco system, so Aztec engineers built a dyke crossing the middle of the southwestern part of Lake Texcoco to keep most of the farming-friendly fresh water in a more concentrated form in the southern zone of the lake system. This left a large part Lake Texcoco not suitable for chinampa-based farming. The wealthy Kingdom of Texcoco on the eastern shores of the lake with the same name had no chinampas owing to the brackish and swampy nature of their portion of the lake. The small kingdom that would later be incorporated into the Aztec Empire often worked with the Tenochtitlán Aztecs on shared water issues including cooperating during times of flood. For more information on the Kingdom of Texcoco please see Mexico Unexplained episode number 133: https://mexicounexplained.com//the-tragic-history-of-the-house-of-texcoco/. At the time of the Spanish arrival the island city of Xaltocan in the northern section of the Lake Texcoco system had chinampas surrounding it because the water there was a little less salty than the waters immediately to the south, but the bulk of the chinampas were in that cordoned off southwest part of the lake system. The Spanish noted that the island city of Tenochtitlán had probably grown over the years because of chinampa farming ringing the island. The canals of the older chinampas closer to the island’s shores were gradually filled in thus giving the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlán more room to expand. The bulk of the chinampas in the lake area existed in Xochimilco and Chalco where people grew corn, squash, beans, amaranth, tomatoes, peppers, flowers, and herbs. The chinampas around Tenochtitlán grew these traditional crops as well, but also grew fruits and vegetables from other parts of the empire. The Spanish marveled at the variety of the plants growing in the chinampas surrounding the imperial capital. The Spanish also wrote that chinampas were passed down through families in wills and many families had been tending to the same group of chinampas for 6 or 7 generations.

While chinampas are often seen as an Aztec invention dating back less than a thousand years, there is evidence showing that other cultures used the chinampas farming method in other parts of ancient Mexico. At Laguna de Magdalena in the Mexican state of Jalisco about 35 northwest of Guadalajara, archaeologists have discovered ancient chinampas dating back to between 400 and 700 AD. This would pre-date the Aztecs by several centuries. The archaeology of western Mexico is not as thoroughly documented as central Mexico or the Maya area, so researchers have a hard time assigning a culture to the builders of the chinampas at Lake Magdalena. Most agree that they belonged to the little-understood Teuchitlán tradition, a mysterious culture known for their shaft tombs, circular buildings, and whimsical clay figurines. No one knows if the chinampa farming method originated in western Mexico and spread to the central lake region or the other way around.

Do chinampas exist in the modern world? The 1968 Mexico City Olympics did not completely destroy the chinampa culture. The famous “Floating Gardens of Xochimilco” had been an attraction drawing foreign tourists long before the Olympics and for some decades after. Besides the all-but faded out tourist industry in the remaining canals, there are relics of the once great chinampa fields that survive into the present century. Many plots of land farmed by families since before the Spanish Conquest are still in use in the towns of Tlahuac, San Gregorio, San Luis and Mixquic, all around Xochimilco. These chinampas exist in canals and lagoons in the parts of Lake Xochimilco that haven’t been either purposefully drained or have just dried up. As Mexico City grows and its thirst for water increases, the chinampas farmers find it more difficult to maintain the canals in the face of uncertain water levels. The centuries old chinampas face threats from urban sprawl, the presence of pesticides and other toxins in the water, and a fading interest in this unique form of agriculture among the younger generations. While there have been some chinampa revitalization efforts in the first few years of the 21st Century, many do not expect this way of life to last for more than 25 years into the future in Mexico.

Do chinampas exist in the modern world? The 1968 Mexico City Olympics did not completely destroy the chinampa culture. The famous “Floating Gardens of Xochimilco” had been an attraction drawing foreign tourists long before the Olympics and for some decades after. Besides the all-but faded out tourist industry in the remaining canals, there are relics of the once great chinampa fields that survive into the present century. Many plots of land farmed by families since before the Spanish Conquest are still in use in the towns of Tlahuac, San Gregorio, San Luis and Mixquic, all around Xochimilco. These chinampas exist in canals and lagoons in the parts of Lake Xochimilco that haven’t been either purposefully drained or have just dried up. As Mexico City grows and its thirst for water increases, the chinampas farmers find it more difficult to maintain the canals in the face of uncertain water levels. The centuries old chinampas face threats from urban sprawl, the presence of pesticides and other toxins in the water, and a fading interest in this unique form of agriculture among the younger generations. While there have been some chinampa revitalization efforts in the first few years of the 21st Century, many do not expect this way of life to last for more than 25 years into the future in Mexico.

While the unbroken link to the pre-Hispanic Aztecs might be severed in the coming decades, many permaculture groups in various parts of the world have been experimenting with chinampa agriculture in their local areas. Perhaps people in China, the Netherlands or even the United States may carry the torch and breathe new life into this fascinating and important part of ancient Mexican culture.

REFERENCES

Calnek, Edward E., “Settlement Pattern and Chinampa Agriculture,” American Antiquity 1972, 37(104-15)

Popper, Virginia. “Investigating Chinampa Farming,” Backdirt, Cotsen Institute of Archaeology – UCLA, Fall/Winter 2000.

Williams, Eduardo. “Prehispanic West Mexico: A Mesoamerican Cultural Area.” Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies, Inc.