Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

While collecting firewood to supplement income for his family, teenager Juan Quezada Celado stopped in a small cave to take a break. The year was 1954. He had been to this part of the Sierras in northern Chihuahua many times to gather wood for his family’s use and to sell to others. Young Juan had quit school to help out his family, struggling like so many others in the small town of Mata Ortiz. While taking a break in the cave, the teenage boy discovered a perfectly intact pot with intricately painted designs, along with pieces of pottery strewn about the floor of the cave. Later Quezada would discover that the pottery belonged to a long-forgotten culture called the Mogollon, also known as the Casas Grandes or Paquimé, named for a major archaeological site nearby. For a brief overview of this ancient civilization, please see Mexico Unexplained episode number 66: https://mexicounexplained.com//lost-city-paquime-casas-grandes-culture/ It was difficult for Quezada to carry the pot back home to the dusty town of Mata Ortiz along with his firewood, but the pot made it intact and the teenage boy added it to his growing collection of ancient pots and pottery fragments. The young Quezada knew one day that he would do something with this expanding collection, he just didn’t know what.

While collecting firewood to supplement income for his family, teenager Juan Quezada Celado stopped in a small cave to take a break. The year was 1954. He had been to this part of the Sierras in northern Chihuahua many times to gather wood for his family’s use and to sell to others. Young Juan had quit school to help out his family, struggling like so many others in the small town of Mata Ortiz. While taking a break in the cave, the teenage boy discovered a perfectly intact pot with intricately painted designs, along with pieces of pottery strewn about the floor of the cave. Later Quezada would discover that the pottery belonged to a long-forgotten culture called the Mogollon, also known as the Casas Grandes or Paquimé, named for a major archaeological site nearby. For a brief overview of this ancient civilization, please see Mexico Unexplained episode number 66: https://mexicounexplained.com//lost-city-paquime-casas-grandes-culture/ It was difficult for Quezada to carry the pot back home to the dusty town of Mata Ortiz along with his firewood, but the pot made it intact and the teenage boy added it to his growing collection of ancient pots and pottery fragments. The young Quezada knew one day that he would do something with this expanding collection, he just didn’t know what.

Although the ceramic fragments the young Juan Quezada had been finding in the vicinity of his town had dated back 700 to possibly over a thousand years old, the town of Mata Ortiz is relatively new. The town was established in 1909 and was first called Pearson, named after American entrepreneur Frederick Stark Pearson. Pearson’s massive international business empire included the Mexican North West Railway and the Mexican Tramway Company. The railway company not only connected many points in the Mexican states of Chihuahua and Sonora, it also acquired the logging rights to three million acres of timber in the Sierra Madre Occidental, the long mountain range running along the western side of Mexico. The future town of Mata Ortiz became the site of the largest timber mill in the entire world, where newly felled trees were processed before they were loaded on the rail cars and shipped to the United States. Later Pearson established a rail repair  yard just outside of town. The enterprising American established his namesake town with a small colony of Canadians, but because of the ample work available, many Mexicans from the surrounding small towns and ranchos established themselves in the fledgling settlement of Pearson and in a few years it turned into a bustling town. Pearson’s days were numbered, though, as the Mexican Revolution severely impacted Frederick Pearson’s business model. By 1915, he had lost everything when future Mexican president Venustiano Carranza nationalized many foreign-owned companies while he was Head of the Preconstitutional Government. The government-run timber mill Pearson had established shut down in 1921. The closure of the mill was a big blow to the local economy. In 1924, the Mexican government renamed the town Mata Ortiz in honor of Juan Mata Ortiz, a local man who made a name for himself in the Apache Wars of the previous century. Juan Quezada, born in 1940, moved to the town of Mata Ortiz as an infant. By the time he became a young adult the local economy had suffered what seemed to be its final blow when the railroad repair yard that Frederick Pearson built decades earlier was shut down and moved north to the more populated town of Nuevo Casas Grandes. The few hundred people left in Mata Ortiz barely hung on by making meager livings from seasonal agriculture, gathering firewood in the mountains and harvesting wild maguey plants.

yard just outside of town. The enterprising American established his namesake town with a small colony of Canadians, but because of the ample work available, many Mexicans from the surrounding small towns and ranchos established themselves in the fledgling settlement of Pearson and in a few years it turned into a bustling town. Pearson’s days were numbered, though, as the Mexican Revolution severely impacted Frederick Pearson’s business model. By 1915, he had lost everything when future Mexican president Venustiano Carranza nationalized many foreign-owned companies while he was Head of the Preconstitutional Government. The government-run timber mill Pearson had established shut down in 1921. The closure of the mill was a big blow to the local economy. In 1924, the Mexican government renamed the town Mata Ortiz in honor of Juan Mata Ortiz, a local man who made a name for himself in the Apache Wars of the previous century. Juan Quezada, born in 1940, moved to the town of Mata Ortiz as an infant. By the time he became a young adult the local economy had suffered what seemed to be its final blow when the railroad repair yard that Frederick Pearson built decades earlier was shut down and moved north to the more populated town of Nuevo Casas Grandes. The few hundred people left in Mata Ortiz barely hung on by making meager livings from seasonal agriculture, gathering firewood in the mountains and harvesting wild maguey plants.

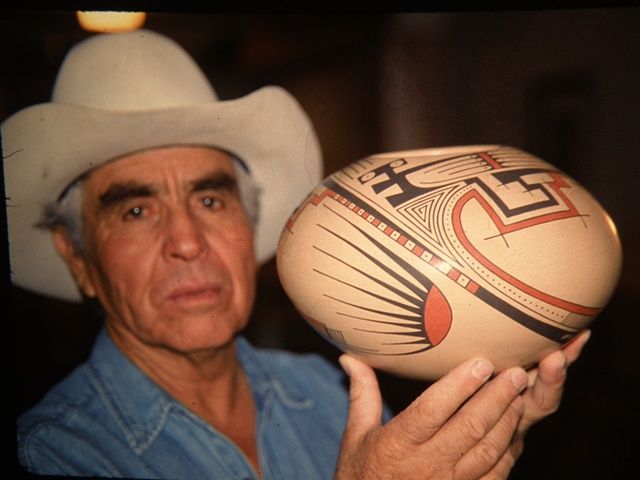

The economic situation in the region unexpectedly changed in the 1960s. Using his collection of ancient pots and pottery fragments as an inspiration, Juan Quezada endeavored to revive the local ceramic traditions dating back thousands of years. Quezada was no potter, but he figured that since he found an overabundance of artifacts, there must be an unlimited supply of the materials that went into making the pottery to be found locally. He studied the pieces in his collection and went searching for the clay first, which was easy to find as the town of Mata Ortiz is in the fertile river valley of the Rio Palanganas. From studying the broken pieces, Quezada discovered that the ancients used sand and other coarse materials to serve the function of what ceramicists call a  “temper.” Potters add a temper to clay to prevent cracking and shrinkage during the drying and firing processes. Quezada did not use a potter’s wheel but rather employed the single coil method to build up the pots from a flat tortilla-shaped piece of clay that served as the bottom of the piece. After the pot was fully formed, the coils were smoothed out with a hacksaw blade before Quezada let the piece dry. The drying process finished, Quezada would smooth out the outside of the pots using deer bones or stones. Before firing, Quezada painted the intricate designs on the surfaces of the vessels, with the ancient pots and pottery fragments in his collection serving as models and inspirations for drawings and geometric patterns. He made paintbrushes using sticks and children’s hair. The paints were made from local minerals as the ancients had done many centuries before. As with the clay, Quezada knew the minerals must have been sourced nearby, so he found their various sources. After the surface designs dried, the pots needed to be fired. Quezada had heard that the pueblo potters of New Mexico were using cow dung to fire their clay vessels, so he tried that. By the early 1970s Juan Quezada had perfected his technique without any formal instruction and brought back to life successfully the crafts of the Mimbres and Mogollon peoples of old. At first, Quezada gave away most of his pots to family and friends as gifts. By the mid-1970s, he started selling his wares to people passing through town for the equivalent of several dollars apiece, which was more than what he could get for a week’s worth of gathering firewood. It was not long before the outside world started to notice the wonderful work coming out of this unknown corner of the state of Chihuahua.

“temper.” Potters add a temper to clay to prevent cracking and shrinkage during the drying and firing processes. Quezada did not use a potter’s wheel but rather employed the single coil method to build up the pots from a flat tortilla-shaped piece of clay that served as the bottom of the piece. After the pot was fully formed, the coils were smoothed out with a hacksaw blade before Quezada let the piece dry. The drying process finished, Quezada would smooth out the outside of the pots using deer bones or stones. Before firing, Quezada painted the intricate designs on the surfaces of the vessels, with the ancient pots and pottery fragments in his collection serving as models and inspirations for drawings and geometric patterns. He made paintbrushes using sticks and children’s hair. The paints were made from local minerals as the ancients had done many centuries before. As with the clay, Quezada knew the minerals must have been sourced nearby, so he found their various sources. After the surface designs dried, the pots needed to be fired. Quezada had heard that the pueblo potters of New Mexico were using cow dung to fire their clay vessels, so he tried that. By the early 1970s Juan Quezada had perfected his technique without any formal instruction and brought back to life successfully the crafts of the Mimbres and Mogollon peoples of old. At first, Quezada gave away most of his pots to family and friends as gifts. By the mid-1970s, he started selling his wares to people passing through town for the equivalent of several dollars apiece, which was more than what he could get for a week’s worth of gathering firewood. It was not long before the outside world started to notice the wonderful work coming out of this unknown corner of the state of Chihuahua.

The few outside traders who first got their hands on these pots passed off Quezada’s works as ancient, until Juan Quezada started signing his pieces. Quezada received a big boost in an unsuspecting way when an American anthropologist named Spencer MacCallum stumbled upon some of Quezada’s pots at a store called Bob’s Swap Shop located in Deming in southern New Mexico. The pots dazzled the American anthropologist and MacCallum started asking questions. The owner of the store told him that the pots were brought in by a Mexican family that had traded them for some used clothing. The pots were priced at $18.00 each, which was considered expensive in the 1970s, but MacCallum bought all of them. Armed only with the knowledge that these wonderful creations came from someplace immediately south of the border, he decided to try to find the source of the pots and crossed the border into Mexico with photographs. Two hours into Mexico, he made it to Nuevo Casas Grandes and he showed the photos around and asked questions. People directed MacCullum to the town of Mata Ortiz, immediately south of Nuevo Casas Grandes. When he pulled into town, a young boy riding a burro led him to the Quezada workshops. MacCallum saw great potential in this style of pottery which seemed to complement similar types coming out of the Southwestern pueblos. With “Santa Fe Style” coming out of New Mexico and spreading across the US in the late 1970s, MacCallum saw a greater marketing potential. Gallery owners, curio vendors and museums agreed: The dazzling geometric and stylized animal patterns on Quezada’s pieces were reminiscent of the art of the pueblos. Galleries and other venues throughout the American Southwest and California began carrying Quezada’s ceramics. For eight years Spencer MacCallum would serve as Juan Quezada’s agent and helped him promote the Mata Ortiz pottery style far and wide.

As the demand grew throughout the late 1970s, Quezada recognized the need to teach family members his pottery style so that they could meet this demand head-on. Juan’s sister Lydia took to the craft quickly and became an expert potter who would later gain worldwide acclaim. Family members taught other family members and friends, and before long a good percentage of the town was engaged in making clay handcrafts. The two main “hubs” of pottery making in Mata Ortiz throughout the 1980s were centered around the Quezada property, with workshops in adjacent homes of immediate family and in the El Porvenir neighborhood with workshops under the supervision of Félix Ortiz. Purists at the time saw the pots from the Félix Ortiz workshops to be of lesser quality, but they still sold, as the demand for this style increased almost exponentially. By the end of the decade many other people in the town of Mata Ortiz started making pots on their own without the help or guidance of Juan Quezada or Félix Ortiz using prehistoric pottery fragments found locally as inspiration. The star of the town and the outward face of Mata Ortiz pottery, though, was always Juan Quezada. He toured parts of the US with an exhibit called “Juan Quezada and the New Tradition” that caused increased interest in Mata Ortiz crafts among American collectors and Quezada made various museum and gallery appearances throughout the ‘80s and ‘90s. The “New Traditions” exhibit eventually ended up as part of the permanent collection of the Museum of Us, formerly known as the San Diego Museum of Man, located in the museum promenade in Balboa Park, in the heart of San Diego, California. Arguably, Mata Ortiz pottery reached its peak popularity in the United States in the 1990s as interest in Southwestern-themed handcrafts and “Santa Fe Style” had waned by the end of the decade. With all this attention for many years north of the border and in other foreign markets such as Germany, there was very little interest coming out of Mexico itself until the very end of the 1990s.

As the demand grew throughout the late 1970s, Quezada recognized the need to teach family members his pottery style so that they could meet this demand head-on. Juan’s sister Lydia took to the craft quickly and became an expert potter who would later gain worldwide acclaim. Family members taught other family members and friends, and before long a good percentage of the town was engaged in making clay handcrafts. The two main “hubs” of pottery making in Mata Ortiz throughout the 1980s were centered around the Quezada property, with workshops in adjacent homes of immediate family and in the El Porvenir neighborhood with workshops under the supervision of Félix Ortiz. Purists at the time saw the pots from the Félix Ortiz workshops to be of lesser quality, but they still sold, as the demand for this style increased almost exponentially. By the end of the decade many other people in the town of Mata Ortiz started making pots on their own without the help or guidance of Juan Quezada or Félix Ortiz using prehistoric pottery fragments found locally as inspiration. The star of the town and the outward face of Mata Ortiz pottery, though, was always Juan Quezada. He toured parts of the US with an exhibit called “Juan Quezada and the New Tradition” that caused increased interest in Mata Ortiz crafts among American collectors and Quezada made various museum and gallery appearances throughout the ‘80s and ‘90s. The “New Traditions” exhibit eventually ended up as part of the permanent collection of the Museum of Us, formerly known as the San Diego Museum of Man, located in the museum promenade in Balboa Park, in the heart of San Diego, California. Arguably, Mata Ortiz pottery reached its peak popularity in the United States in the 1990s as interest in Southwestern-themed handcrafts and “Santa Fe Style” had waned by the end of the decade. With all this attention for many years north of the border and in other foreign markets such as Germany, there was very little interest coming out of Mexico itself until the very end of the 1990s.

In 1999 Quezada had his first major Mexican exhibit at the Franz Mayer Museum in Mexico City, the home of Latin America’s largest collection of decorative arts. That same year, Mexican president Ernesto Zedillo presented to Juan Quezada the National Prize for Arts and Sciences. Quezada won the prize in the handcrafts and folk-art category and returned to the town of Mata Ortiz with a gold medal and 520,000 pesos. Quezada then bought a small rancho on a rocky riverbank of the Palanganas River overlooking the town. He christened his ranch Rancho Barro Blanco, or “The White Clay Ranch,” in English. He currently maintains his original house in the town itself where he still has his workshop. His eight children and many grandchildren still carry on the tradition he helped reestablish many decades ago. With hundreds of people now engaged in the creation of these wonderful pieces of folk art, Mata Ortiz pottery will certainly continue for many years to come.

In 1999 Quezada had his first major Mexican exhibit at the Franz Mayer Museum in Mexico City, the home of Latin America’s largest collection of decorative arts. That same year, Mexican president Ernesto Zedillo presented to Juan Quezada the National Prize for Arts and Sciences. Quezada won the prize in the handcrafts and folk-art category and returned to the town of Mata Ortiz with a gold medal and 520,000 pesos. Quezada then bought a small rancho on a rocky riverbank of the Palanganas River overlooking the town. He christened his ranch Rancho Barro Blanco, or “The White Clay Ranch,” in English. He currently maintains his original house in the town itself where he still has his workshop. His eight children and many grandchildren still carry on the tradition he helped reestablish many decades ago. With hundreds of people now engaged in the creation of these wonderful pieces of folk art, Mata Ortiz pottery will certainly continue for many years to come.

To buy Mata Ortiz pots directly from author Robert Bitto’s store, click here: https://www.ebay.com/str/suenosimports/Mata-Ortiz-Pottery/_i.html?_storecat=31106425010

REFERENCES

Banamex. Grandes Maestros del Arte Popular Mexicano.Mexico City: Collección Fomento Cultural Banamex. 2001. pp. 57–58 We are Amazon affiliates. To get the book on Amazon, click here: https://amzn.to/3jXXpUR

PBS. Frontline World. “Mexico – The Ballad of Juan Quezada.” May, 2005.

2 thoughts on “Juan Quezada and the Story of Mata Ortiz”

Robert Bitto Mi Nombre Es Juan (soy Cubano) Vivo en Los Estados Unidos Recibi Un Spam De Apoyo a Un “SHOW” Tengo la direccion De El cajon en MESA California,cuando Este Disponible te enviare y te pedire mas acerca de que show y quien eres para conocerte (NO SOY CHOTA) Soy Renegado Y Tambien tengo desde hace decadas un “SHOW” en mi mente A lo mejor Podriamos comenzar una muy buena amistad como asociados loque tengo en mente (LOHAGO) noi importa cuanto trabajo se me haga pasar Soy Decidido…. Y aunque Muchos no lo imaginan mi abuelo Era Mexicano soy Nieto de Hector rodriguez trillos Un Pelotero (jugador de beisball) Famoso se caso Dos Veces LE GUSTABAN LAS MULATAS IGUAL QUE AMI LAS INDIGENAS.. Te Enviare Cuando Este disponible La donacion ..Estoy en movidas Tanbien tengo Shows Por Ejecutar

Lo siento Juan, pero solo puedo entender la mitad de lo que escribiste. ¿Podría aclarar algunas cosas?