Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

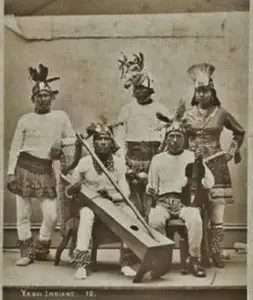

Texas Tech professor William Curry Holden spent Christmas of 1933 in Mexico City. He was there to get permission from the Mexican government to undertake an expedition into the heart of the territory of the Yaqui people. The Yaqui, also known as the Yoeme, had had an uneasy relationship with the outside world that spanned almost 400 years. Most of what was known about the Yaqui to outsiders had to do with warfare and other forms of violent resistance. The Texas anthropologist and historian wanted to learn more about the history, folklore and overall culture of these people to get a sense of who they were beyond the “hostile Indian” label that had been assigned to them for centuries. Authorities in Mexico City welcomed the idea of Dr. Holden’s expedition as the Mexican government sought to repair some of the damage it had done to these people, especially during the previous few decades. The professor was particularly fascinated by accounts of Yaquis still holding out in the high sierras of Sonora and Chihuahua living a traditional and autonomous existence away from Mexican governmental control and the rest of civilization. Hundreds of people known as Mountain Yaquis eluded authority and continued their own special kind of defiance. In the 1930s, their leader was Jesus Munguia. Once a chief in the Yaqui villages in the 1920s, after the last battles in the so-called Yaqui Wars, Munguia joined the Yaquis living in the sierras. While on his 1934 expedition, William Curry Holden hoped to meet with this renegade indigenous leader. The professor wrote this in his diary at the time:

Texas Tech professor William Curry Holden spent Christmas of 1933 in Mexico City. He was there to get permission from the Mexican government to undertake an expedition into the heart of the territory of the Yaqui people. The Yaqui, also known as the Yoeme, had had an uneasy relationship with the outside world that spanned almost 400 years. Most of what was known about the Yaqui to outsiders had to do with warfare and other forms of violent resistance. The Texas anthropologist and historian wanted to learn more about the history, folklore and overall culture of these people to get a sense of who they were beyond the “hostile Indian” label that had been assigned to them for centuries. Authorities in Mexico City welcomed the idea of Dr. Holden’s expedition as the Mexican government sought to repair some of the damage it had done to these people, especially during the previous few decades. The professor was particularly fascinated by accounts of Yaquis still holding out in the high sierras of Sonora and Chihuahua living a traditional and autonomous existence away from Mexican governmental control and the rest of civilization. Hundreds of people known as Mountain Yaquis eluded authority and continued their own special kind of defiance. In the 1930s, their leader was Jesus Munguia. Once a chief in the Yaqui villages in the 1920s, after the last battles in the so-called Yaqui Wars, Munguia joined the Yaquis living in the sierras. While on his 1934 expedition, William Curry Holden hoped to meet with this renegade indigenous leader. The professor wrote this in his diary at the time:

“We were not able to make contact with Jesus Munguia. He refused to comply with the last treaty between the Yaquis and the Mexican government. For the past five years he has been the chief of the Mountain Yaquis. As we were under the constant surveillance of the Mexican Army, we had no opportunity to arrange a meeting with Munguia. The Mountain Yaquis are regarded by the Mexican government as outlaws and are shot on sight. The army guards the lower ends of the passes in an effort to prevent communication between the Mountain Yaquis and those in the river villages. We ascertained, however, that the two groups have an understanding between them, and that the river Yaquis help support the mountain people.”

Holden’s assumptions were correct. The renegade mountain people never lost communication with their brothers and sisters living a more settled and guarded existence in the villages along the Rio Yaqui. The mountain people had a distinct history, though, which earned them the special designation of “Mountain Yaqui.” How did this breakaway group form and why the continued aggressive resistance from them well into the 20th Century?

For thousands of years the Yaquis – also known as the Yoeme – and their ancestors occupied parts of the American Southwest and parts of the Mexican states of Sinaloa, and Durango, but their core homeland has always been the Yaqui River valley of Sonora. Most of the Yaqui people lived in villages and cultivated corn, beans and squash. The first documented encounter between Yaquis and Europeans was in 1533 when a small expedition led by Diego de Guzmán entered Yaqui territory. In the early 1500s the Yaquis numbered about 30,000 living in almost 80 villages which were mostly located near the Yaqui River. When the first group of Yaquis met the Spanish face to face, a tribal elder literally made a line in the sand for the Spanish not to cross and told Guzmán to leave the area, refusing him food, water and shelter. A battle ensued and the Spanish retreated. Thirty years later an attempt to set up a Spanish colony in Yaqui territory failed and the settlers were driven back to central Mexico. In 1608 the Spanish and the Yaquis clashed once again, resulting in two disastrous defeats for the Spanish. A peace agreement was reached in 1610 and the Jesuits arrived seven years later to set up missions in Yaqui territory. The 150-year relationship the Yaquis had with the Jesuits was mutually beneficial and for the most part peaceful. The Jesuits ministered to the natives and set up small industry, the Indians got to keep most of their culture, their lands and social structure. The discovery of silver in Yaqui territory in 1684 caused some tensions between natives and Europeans once again but this did not cause the Yaquis to revolt. The next big uprising would be in 1740 when 5,000 Yaquis and 1,000 Spaniards were killed. The central government in Mexico City then decided to tighten control over these people. The Jesuits, long-time advocates for the Yaqui, had been losing power in the region by the mid-1700s and by the 1760s they were completely expelled from Mexico. With the departure of the Jesuits and the closing down of some of the missions, the Yaquis and the Spanish maintained an uneasy peace until the Mexican War of Independence began in 1810 and the Yaquis faced new challenges from a new group of people who now attempted to rule them from faraway Mexico City. During the Mexican fight for independence, while the government of Sonora and the Spanish elites of the area sided with the Spanish Crown, the Yaquis remained neutral and refused to participate in the conflict. To the new authorities in Mexico City, this indicated that the Yaquis considered themselves not to be subject to outside rule. The newly formed Mexican government, seeking to integrate all the territories of former New Spain into the new political unit called Mexico, sent tax collectors to Yaqui lands proclaiming that the Yaquis were citizens of a new nation which needed money in its treasury. Given the Yaqui history of resistance to outside intervention, the tax collecting project did not go well. A revolt in 1825 beat back the new central Mexican government, but it returned intent on controlling every inch of Sonora. Thus began a series of minor revolts, skirmishes and guerilla attacks for the next 50 years until the Yaquis under the leadership of Cajemé proclaimed the new Yaqui republic in 1876. For more information on the Yaqui Indian Republic, please see Mexico Unexplained Episode number 35. https://mexicounexplained.com/cajeme-yaqui-indian-republic/

For thousands of years the Yaquis – also known as the Yoeme – and their ancestors occupied parts of the American Southwest and parts of the Mexican states of Sinaloa, and Durango, but their core homeland has always been the Yaqui River valley of Sonora. Most of the Yaqui people lived in villages and cultivated corn, beans and squash. The first documented encounter between Yaquis and Europeans was in 1533 when a small expedition led by Diego de Guzmán entered Yaqui territory. In the early 1500s the Yaquis numbered about 30,000 living in almost 80 villages which were mostly located near the Yaqui River. When the first group of Yaquis met the Spanish face to face, a tribal elder literally made a line in the sand for the Spanish not to cross and told Guzmán to leave the area, refusing him food, water and shelter. A battle ensued and the Spanish retreated. Thirty years later an attempt to set up a Spanish colony in Yaqui territory failed and the settlers were driven back to central Mexico. In 1608 the Spanish and the Yaquis clashed once again, resulting in two disastrous defeats for the Spanish. A peace agreement was reached in 1610 and the Jesuits arrived seven years later to set up missions in Yaqui territory. The 150-year relationship the Yaquis had with the Jesuits was mutually beneficial and for the most part peaceful. The Jesuits ministered to the natives and set up small industry, the Indians got to keep most of their culture, their lands and social structure. The discovery of silver in Yaqui territory in 1684 caused some tensions between natives and Europeans once again but this did not cause the Yaquis to revolt. The next big uprising would be in 1740 when 5,000 Yaquis and 1,000 Spaniards were killed. The central government in Mexico City then decided to tighten control over these people. The Jesuits, long-time advocates for the Yaqui, had been losing power in the region by the mid-1700s and by the 1760s they were completely expelled from Mexico. With the departure of the Jesuits and the closing down of some of the missions, the Yaquis and the Spanish maintained an uneasy peace until the Mexican War of Independence began in 1810 and the Yaquis faced new challenges from a new group of people who now attempted to rule them from faraway Mexico City. During the Mexican fight for independence, while the government of Sonora and the Spanish elites of the area sided with the Spanish Crown, the Yaquis remained neutral and refused to participate in the conflict. To the new authorities in Mexico City, this indicated that the Yaquis considered themselves not to be subject to outside rule. The newly formed Mexican government, seeking to integrate all the territories of former New Spain into the new political unit called Mexico, sent tax collectors to Yaqui lands proclaiming that the Yaquis were citizens of a new nation which needed money in its treasury. Given the Yaqui history of resistance to outside intervention, the tax collecting project did not go well. A revolt in 1825 beat back the new central Mexican government, but it returned intent on controlling every inch of Sonora. Thus began a series of minor revolts, skirmishes and guerilla attacks for the next 50 years until the Yaquis under the leadership of Cajemé proclaimed the new Yaqui republic in 1876. For more information on the Yaqui Indian Republic, please see Mexico Unexplained Episode number 35. https://mexicounexplained.com/cajeme-yaqui-indian-republic/

After the failure of one of the only attempts to set up a fully independent indigenous nation in the Western Hemisphere, the Yaquis were beaten down again. By the late 1800s under the dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz, many Yaqui people already lived a nomadic existence in the mountains of Sonora and Chihuahua, sometimes raiding Mexican and American settlements much as the Comanche and Apaches had done before them. The Mountain Yaquis often battled raiders from the other indigenous groups, only feeling loyal to themselves and to their fellow Yaquis they left behind in the villages of their ancestral homeland which were now heavily guarded by the Mexican government. Government officials sometimes provoked the Yaquis living in the river valley in order to confiscate land or to make an excuse to dismantle villages and deport people. In the late 1800s Yaquis were often sold into slavery at 60 pesos per head and shipped to Oaxaca to work on the sugar and tobaccos plantations or sent farther afield to the Yucatán where they worked cultivating henequen under the brutal direction of wealthy hacienda owners. Most Yaquis did not survive these harsh and alien conditions and after a few decades of these slaving practices, many Yaquis decided to flee the homeland instead of being deported. Some went north or to the larger cities of central Mexico and others joined their brothers and sisters in the mountains. During the time of Yaqui enslavement, the Mountain Yaqui often came to the assistance of the villagers by waging small guerrilla-warfare-style battles from their mountain retreats. Whenever the Mexican military or civil authorities tried to battle the Mountain Yaqui on their own turf, they found mountain passes impassible or the mountain people just too elusive for capture. The Mountain Yaqui adopted the coyote as their totemic spirit animal because the coyote was swift, cunning and could easily evade those who pursued him. They even had a special nighttime coyote dance to call upon the spirit of the animal that is still practiced by their descendants.

In order to communicate with other Yaquis living in the traditional villages and scattered throughout the north of Mexico and the Southwestern US, the Mountain Yaquis established a series of secret trails spanning many hundreds of miles through the sierras. These trails also served as vital supply lines and stretched from the central mountains of Sonora clear to the borders of Texas, New Mexico, Arizona and deep into southern Chihuahua. A trail leading through northern Chihuahua to the “bootheel” of New Mexico and into the Chiricahua Mountains of southeastern Arizona became the chief byway through which the Mountain Yaquis received guns and munitions. Yaquis working on the American side of the border would buy weapons in the US and pass them to fellow Mountain Yaquis through this hundreds-mile-long supply line. A well-armed contingent of Mountain Yaquis together with dozens of Pima or O’odham people raided the customs house at Nogales on August 12, 1896. This group was riled up by promises of local Mexicans that their actions would eventually lead to the overthrow of the government of Porfirio Díaz, which as mentioned previously, was not kind to the Yaqui people. This border raid conducted by the Mountain Yaqui is known in history as the “Yaqui Uprising” and included skirmishes on both sides of the international border. Battling against the Yaquis was a combined force of Mexican army, American militia, US Buffalo Soldiers and local police from the Mexican and American sides. Very few Yaquis were captured and those who weren’t retreated into the mountains using their famous trail network to “disappear.” A large contingent of Mexican troops in hot pursuit failed to catch even one of the Mountain Yaqui rebels. Two companies of the US Army’s 24th infantry crossed the border into Mexican territory to conduct their own operation but returned to the American side after a few weeks with nothing to show for their efforts.

In order to communicate with other Yaquis living in the traditional villages and scattered throughout the north of Mexico and the Southwestern US, the Mountain Yaquis established a series of secret trails spanning many hundreds of miles through the sierras. These trails also served as vital supply lines and stretched from the central mountains of Sonora clear to the borders of Texas, New Mexico, Arizona and deep into southern Chihuahua. A trail leading through northern Chihuahua to the “bootheel” of New Mexico and into the Chiricahua Mountains of southeastern Arizona became the chief byway through which the Mountain Yaquis received guns and munitions. Yaquis working on the American side of the border would buy weapons in the US and pass them to fellow Mountain Yaquis through this hundreds-mile-long supply line. A well-armed contingent of Mountain Yaquis together with dozens of Pima or O’odham people raided the customs house at Nogales on August 12, 1896. This group was riled up by promises of local Mexicans that their actions would eventually lead to the overthrow of the government of Porfirio Díaz, which as mentioned previously, was not kind to the Yaqui people. This border raid conducted by the Mountain Yaqui is known in history as the “Yaqui Uprising” and included skirmishes on both sides of the international border. Battling against the Yaquis was a combined force of Mexican army, American militia, US Buffalo Soldiers and local police from the Mexican and American sides. Very few Yaquis were captured and those who weren’t retreated into the mountains using their famous trail network to “disappear.” A large contingent of Mexican troops in hot pursuit failed to catch even one of the Mountain Yaqui rebels. Two companies of the US Army’s 24th infantry crossed the border into Mexican territory to conduct their own operation but returned to the American side after a few weeks with nothing to show for their efforts.

After the Yaqui Uprising of 1896, the Mountain Yaquis continued their cat-and-mouse game with the Mexican authorities, raiding and occasionally skirmishing with the Mexican military. By 1903, the government of Porfirio Díaz came up with a plan to deport all Yaquis in northern Mexico to Oaxaca or the Yucatán. Despite clashes with armed resistors from the mountains, tens of thousands of Yaquis were transported far away to the tropics to work the plantations. This practice only ended with the start of the Mexican Revolution in 1910, but the story of the Mountain Yaqui does not end there. During the Mexican Revolution they continued their resistance often joining various Mexican rebel factions seeking to upend the status quo. In a curious historical  footnote, in January of 1918 a group of 30 armed Mountain Yaquis were intercepted by Buffalo Soldiers of the 10th Cavalry just across the border at Arivaca, Arizona. The battle that followed – in which the Yaqui commander was killed and half of his men captured – is considered the final conflict that the US Army had against any indigenous group on American soil, thus ending the long chapter in US military history known as “The Indian Wars.” The resistance in Sonora and Chihuahua continued into the late 1920s with another uprising of the Mountain Yaqui called by historians, “The Yaqui Revolt of 1926-1928.” This time the Mexican military took to the remote and inaccessible sierras and fought the Mountain Yaqui on their home territory. They used everything at their disposal to fight them, including airplanes, machine guns and poison gas that had been deployed in World War One. The last conflict in this uprising is known as the Battle of Cerro del Gallo and that occurred in April of 1927. Hundreds of Mountain Yaquis were taken prisoner after this battle and the rest of the “Revolt” consisted of minor skirmishes. The newly formed Mexican Air Force also bombed hidden mountain encampments by air. By the time of the expedition of Texas Tech professor William Curry Holden in 1934, the Mountain Yaquis were reduced to a few bands of a few dozen each, holding out in the isolated parts of the sierras and relying on outside assistance for their near total survival. By the 1940s the remaining Yaquis left the mountains and either rejoined the Yaquis of the river valley villages or integrated into the larger mestizo Mexican society. As an interesting aside, a state-recognized Native American tribe headquartered in Lubbock, Texas called the Texas Band of Yaqui Indians traces their immediate ancestry to a group of about 80 Mountain Yaquis who fled across the US border under the leadership of a man named Lino. This Texas group has been at the forefront of uniting the descendants of the Mountain Yaqui who scattered during the many decades of Mexican oppression. With a new dedication to preserve the traditional Mountain Yaqui culture and history, this resolute indigenous group will survive the 21st Century and beyond, and will continue their struggle far into the future.

footnote, in January of 1918 a group of 30 armed Mountain Yaquis were intercepted by Buffalo Soldiers of the 10th Cavalry just across the border at Arivaca, Arizona. The battle that followed – in which the Yaqui commander was killed and half of his men captured – is considered the final conflict that the US Army had against any indigenous group on American soil, thus ending the long chapter in US military history known as “The Indian Wars.” The resistance in Sonora and Chihuahua continued into the late 1920s with another uprising of the Mountain Yaqui called by historians, “The Yaqui Revolt of 1926-1928.” This time the Mexican military took to the remote and inaccessible sierras and fought the Mountain Yaqui on their home territory. They used everything at their disposal to fight them, including airplanes, machine guns and poison gas that had been deployed in World War One. The last conflict in this uprising is known as the Battle of Cerro del Gallo and that occurred in April of 1927. Hundreds of Mountain Yaquis were taken prisoner after this battle and the rest of the “Revolt” consisted of minor skirmishes. The newly formed Mexican Air Force also bombed hidden mountain encampments by air. By the time of the expedition of Texas Tech professor William Curry Holden in 1934, the Mountain Yaquis were reduced to a few bands of a few dozen each, holding out in the isolated parts of the sierras and relying on outside assistance for their near total survival. By the 1940s the remaining Yaquis left the mountains and either rejoined the Yaquis of the river valley villages or integrated into the larger mestizo Mexican society. As an interesting aside, a state-recognized Native American tribe headquartered in Lubbock, Texas called the Texas Band of Yaqui Indians traces their immediate ancestry to a group of about 80 Mountain Yaquis who fled across the US border under the leadership of a man named Lino. This Texas group has been at the forefront of uniting the descendants of the Mountain Yaqui who scattered during the many decades of Mexican oppression. With a new dedication to preserve the traditional Mountain Yaqui culture and history, this resolute indigenous group will survive the 21st Century and beyond, and will continue their struggle far into the future.

REFERENCES

(Not a formal bibliography)

“Biografía de José María Leyva Cajeme” In Obras históricas: Reseña histórica del Estado de Sonora by Ramón Corral (in Spanish)

Las razas indígenas de Sonora y la guerra del yaqui by Fortunato Hernández (in Spanish)

Yaqui Resistance and Survival: The Struggle for Land and Autonomy, 1821-1910 by Evelyn Hu-DeHart

Yaqui Myths and Legends by Ruth Warner Giddings

4 thoughts on “Mountain Yaqui, Indigenous Resistance into the 20th Century”

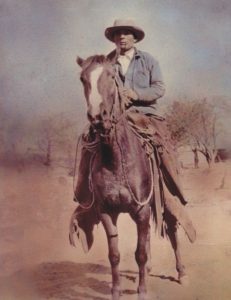

I am curious in your article Mountain Yaqui, Indigenous Resistance into the 20th Century POSTED MAY 9, 2021. It has a photo of a Yaqui man on a horse. Do you happen to have any detail on this person? A family sent it to me telling me it was my Grate Grandfather Ysmael Valenzuela. But I understand that it’s a very common name and I am curious if you could share details to verify if it was him or not? Thanks

Sorry, that photo came from an internet archive of old Yaqui photos and I don’t know anything more about it. Best of luck in your quest!

Hi! Thank you for that. Do you mind sharing the link of the archive with me?

Hello!

Thank you for that. Would you mind sharing a link to this archive or maybe contact information to someone that could share it?