Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

The date was January 9, 1866. US Secretary of State William H. Seward and his delegation sailed into the harbor at Charlotte Amalie on the island of Saint Thomas in the Danish West Indies. Part of a Caribbean cruise Secretary Seward would meet with the Danish governor of the islands and local elites during his brief stay. While on St. Thomas Seward called on a curious local resident, Antonio López de Santa Anna, the 11-time president of Mexico who had been living in this Danish tropical outpost – which would later become the US Virgin Islands – since 1858. Santa Anna left Mexico with millions of pesos and a sizeable entourage and was living a life of a nobleman in a large estate near the Danish governor’s mansion. He received Seward cordially in his library and although their meeting lasted less than an hour, Santa Anna got the mistaken impression that the United States was sympathetic to his return to Mexico and would support him in his quest to become Mexico’s president for the 12th time. Santa Anna closed down his estate and sold off his holdings in the Danish West Indies and moved to New York to plead his case to American politicians and to raise money from wealthy backers who believed in his cause. While living in Staten Island, an American was assigned to the former president of Mexico to be his personal secretary. This man’s name was Thomas Adams. Adams was somewhat of an amateur inventor and was fascinated with something that Santa Anna brought with him to New York. It was a rubbery substance and came from the sap of a tropical tree called the sapodilla. Santa Anna called it chicle. The former Mexican president, originally from Veracruz, had a habit of chewing chicle, but that is not why Santa Anna brought such a large amount of it to the United States. He hoped to find a way to vulcanize the chicle much like Goodyear had done to the sap of the rubber tree. Santa Anna’s idea was to import raw chicle to the US, make it into tires for buggies and thus raise money for his triumphant return to Mexico. Adams and some assistants could not make a viable industrial product out of the elastic tropical sap, but the young inventor did not feel all was lost. Santa Anna got discouraged and returned to Mexico anyway, without American support or the funds he wanted, and left his chicle behind. Thomas Adams could not forget Santa Anna’s chewing gum habit and decided to pursue the manufacture of a new type of chewy gum candy out of what was then Americanized into the word “chicle.” Soon he founded Adams Sons and Company and marketed his Adams New York Gum sold at a penny apiece. He could not keep up with the demand. Adams’ gum would later be called Chicklets.

The date was January 9, 1866. US Secretary of State William H. Seward and his delegation sailed into the harbor at Charlotte Amalie on the island of Saint Thomas in the Danish West Indies. Part of a Caribbean cruise Secretary Seward would meet with the Danish governor of the islands and local elites during his brief stay. While on St. Thomas Seward called on a curious local resident, Antonio López de Santa Anna, the 11-time president of Mexico who had been living in this Danish tropical outpost – which would later become the US Virgin Islands – since 1858. Santa Anna left Mexico with millions of pesos and a sizeable entourage and was living a life of a nobleman in a large estate near the Danish governor’s mansion. He received Seward cordially in his library and although their meeting lasted less than an hour, Santa Anna got the mistaken impression that the United States was sympathetic to his return to Mexico and would support him in his quest to become Mexico’s president for the 12th time. Santa Anna closed down his estate and sold off his holdings in the Danish West Indies and moved to New York to plead his case to American politicians and to raise money from wealthy backers who believed in his cause. While living in Staten Island, an American was assigned to the former president of Mexico to be his personal secretary. This man’s name was Thomas Adams. Adams was somewhat of an amateur inventor and was fascinated with something that Santa Anna brought with him to New York. It was a rubbery substance and came from the sap of a tropical tree called the sapodilla. Santa Anna called it chicle. The former Mexican president, originally from Veracruz, had a habit of chewing chicle, but that is not why Santa Anna brought such a large amount of it to the United States. He hoped to find a way to vulcanize the chicle much like Goodyear had done to the sap of the rubber tree. Santa Anna’s idea was to import raw chicle to the US, make it into tires for buggies and thus raise money for his triumphant return to Mexico. Adams and some assistants could not make a viable industrial product out of the elastic tropical sap, but the young inventor did not feel all was lost. Santa Anna got discouraged and returned to Mexico anyway, without American support or the funds he wanted, and left his chicle behind. Thomas Adams could not forget Santa Anna’s chewing gum habit and decided to pursue the manufacture of a new type of chewy gum candy out of what was then Americanized into the word “chicle.” Soon he founded Adams Sons and Company and marketed his Adams New York Gum sold at a penny apiece. He could not keep up with the demand. Adams’ gum would later be called Chicklets.

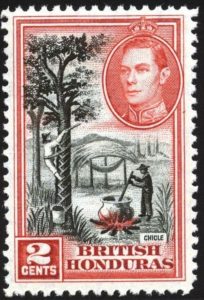

Chicle has been chewed as a gum for thousands of years in Mexico. The ancient Maya called it tzicté yá which loosely translates to “wounded noble tree.” For millennia, chicleros, or those who harvest chicle, have been making zig-zag cuts in the bark of the sapodilla or chicozapote tree, from top to bottom, in the tropical forests of Mexico and Central America. After the chiclero makes the cuts, the tree oozes out a milky latex that is harvested much like maple syrup from a maple tree. The ancient maya chewed the rubbery resin of the tree to quench thirst, to stave off hunger and for ritualistic purposes. Sometimes they would mix chicle with copal resin to make incense. It was believed that the added ingredient of chicle would make the incense burn longer. The Maya traded the chicle with their neighbors and this unique forest product became widely used throughout ancient Mexico. By the time the Spanish arrived in Mexico and encountered the Aztec Empire, European chroniclers noted the use of what the Aztecs called tzictli, a chewing gum made from chicle often combined with other ingredients. They would take the chicle from the forests, usually acquired through trade with other peoples, and mix it with what they called chapapote, black bitumen that washed up on the shores of the Gulf of Mexico. They sometime added to the mix a yellowish oily substance called axin, which was an extract obtained by boiling a small fly-like insect. The phenomenon of chicle use among the Aztecs was documented by Father Bernardino de Sahagun in the Florentine Codex. To the Spanish it was a strange custom and Sahagun remarked “it tires one’s head; it gives one a headache.” In his notes on New Spain, Father Bernardino further elaborates:

Chicle has been chewed as a gum for thousands of years in Mexico. The ancient Maya called it tzicté yá which loosely translates to “wounded noble tree.” For millennia, chicleros, or those who harvest chicle, have been making zig-zag cuts in the bark of the sapodilla or chicozapote tree, from top to bottom, in the tropical forests of Mexico and Central America. After the chiclero makes the cuts, the tree oozes out a milky latex that is harvested much like maple syrup from a maple tree. The ancient maya chewed the rubbery resin of the tree to quench thirst, to stave off hunger and for ritualistic purposes. Sometimes they would mix chicle with copal resin to make incense. It was believed that the added ingredient of chicle would make the incense burn longer. The Maya traded the chicle with their neighbors and this unique forest product became widely used throughout ancient Mexico. By the time the Spanish arrived in Mexico and encountered the Aztec Empire, European chroniclers noted the use of what the Aztecs called tzictli, a chewing gum made from chicle often combined with other ingredients. They would take the chicle from the forests, usually acquired through trade with other peoples, and mix it with what they called chapapote, black bitumen that washed up on the shores of the Gulf of Mexico. They sometime added to the mix a yellowish oily substance called axin, which was an extract obtained by boiling a small fly-like insect. The phenomenon of chicle use among the Aztecs was documented by Father Bernardino de Sahagun in the Florentine Codex. To the Spanish it was a strange custom and Sahagun remarked “it tires one’s head; it gives one a headache.” In his notes on New Spain, Father Bernardino further elaborates:

“And the chewing of chicle is the preference, the privilege of little girls, the small girls, the young women. Also, the mature women, the unmarried women use it; and all the women who are unmarried chew chicle in public. One’s wife also chews chicle, but not in public. Also the widowed and the old women do not, in public chew it. For this reason, the women chew chicle: because thereby they cause their saliva to flow and thereby the mouths are scented; the mouth is given a pleasing taste. With it they dispel the bad odor of their mouths, or the bad smell of their teeth. Thus, they chew chicle in order not to be detested.”

While the ancient Maya had no known taboos surrounding the gum, there was an Aztec social stigma around men chewing chicle in public. Men could chew chicle, but only in private where no one could see them. Chicle was traded openly in the vast markets throughout the Aztec Empire, and some Spanish chroniclers noted that in some areas it was as valuable as cacao beans. Chicle is associated with the goddess Tlazolteotl, a deity from Veracruz who was incorporated into the Aztec pantheon when the Aztecs conquered the Huastecs. The goddess was also associated with childbirth, lust, adultery and the confession of sins. She is often depicted with the bitumen used in the chicle mixture smeared over her mouth.

While the ancient Maya had no known taboos surrounding the gum, there was an Aztec social stigma around men chewing chicle in public. Men could chew chicle, but only in private where no one could see them. Chicle was traded openly in the vast markets throughout the Aztec Empire, and some Spanish chroniclers noted that in some areas it was as valuable as cacao beans. Chicle is associated with the goddess Tlazolteotl, a deity from Veracruz who was incorporated into the Aztec pantheon when the Aztecs conquered the Huastecs. The goddess was also associated with childbirth, lust, adultery and the confession of sins. She is often depicted with the bitumen used in the chicle mixture smeared over her mouth.

During Spanish colonial times and through Mexican independence, chicle was used mostly by people who lived in the areas where the sap of the chicozapote tree was harvested. When Thomas Adams formulated the first chewing gum in the US from chicle in the late 1860s, that is when the demand for this tropical forest product soared. The latter part of the 1800s saw many challenges to meeting the demand.

Most of the trees from which chicle was extracted in Mexico were found in the Yucatán. For the second half of the 1800s the peninsula was in the throes of the Caste War and Maya dissidents fighting the Mexican government managed to control territory with some prime sapodilla forests. Some chicle from the Maya-controlled zones did manage to get out of this area through a backdoor across Mexico’s hazy border with British Honduras. The Maya would trade wood and other forest products to the British for guns until the governments of Porfirio Díaz and Queen Victoria signed the Mariscal-Spencer Treaty of 1889. This treaty not only defined the border between the British colony and Mexico, it prohibited all trade with the rebel Maya and anyone in British territory. The great companies that were emerging in the US to meet the demand of chewing gum had to get what they could from the government-controlled areas of Mexico or suffer the sporadic shipments of inferior-grade chicle coming out of Guatemala and British Honduras. By the turn of the century with the rebel situation in the Yucatán neutralized, Mexican president Porfirio Díaz encouraged foreign investment in the region. Within a few years, most of the Mexican chicle was controlled by three large US corporations: William Wrigley Jr. Company, Beech-Nut Packing Company, and American Chicle Company. These companies, and smaller ones as well, started plantations in Central America and South America with eyes on the long game, knowing that growing the trees to produce chicle would take years to mature.

As a historical aside, William Wrigley Jr. was responsible for most of the promotion of the use of chewing gum in the US in the late 1800s and early 1900s. He once mailed a pack of chewing gum to every household listed in the US phone book. In a heavy lobbying campaign, the Wrigley company convinced the US Army during World War II to include chewing gum in the rations of US soldiers. The soldiers then spread the habit of chewing gum around the world.

As a historical aside, William Wrigley Jr. was responsible for most of the promotion of the use of chewing gum in the US in the late 1800s and early 1900s. He once mailed a pack of chewing gum to every household listed in the US phone book. In a heavy lobbying campaign, the Wrigley company convinced the US Army during World War II to include chewing gum in the rations of US soldiers. The soldiers then spread the habit of chewing gum around the world.

The early 1900s saw many mishaps for the chicle industry. Bad weather struck southern Mexico and Central America in 1904 which resulted in a chicle shortage. There was not enough chicle even in the inferior grades to meet demand and the newly established chicle plantations in other parts of Latin America had not yet begun to produce. In the early Teens they did produce but their quality was not even close to the sap from the wild Mexican trees. By the year 1915 the Mexican Revolution was in full swing, and it came to the Yucatán. Many of the chicleros left the area fleeing the violence or to dodge being conscripted into the Mexican Army, so production suffered. The following year, 1916, across the border in Guatemala rebels opposed to the tyrannical government of President Manuel Estrada Cabrera sabotaged and demolished the main logging and chicle-producing company operating in that country, called Arthes and Sons. American companies became frustrated with political instability, labor issues, low-quality product and questions of sustainability. Many of the older trees became over-tapped and not given enough time for their bark to heal. This left the trees open to attacks by insects, fungus and bacteria, and killed off an estimated 25% of the high-quality trees. Since the chicleros were paid by the pound, many chicle harvesters did not extract the chicle sap with long-term effects in mind and tapped the same trees too frequently. Because of the soaring demand for chewing gum in the US and elsewhere, the gum companies looked for other tropical plants to supply the natural latex for their products. Yields of other species were consistently lower than the sapodilla tree and did not produce the expected quality. Four million kilos of chicle were extracted just from the Yucatán Peninsula in 1942. Botanists and others involved in chicle research gave the forests 25 to 40 years before they faced total depletion.

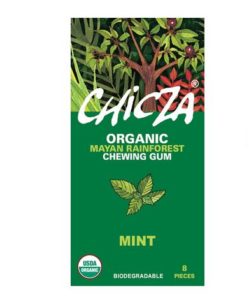

The American chewing gum companies were beginning to see the handwriting on the wall by the late 1930s and early 1940s. Prices of the raw material began to soar at this time, too. During the presidency of Lázaro Cárdenas the Mexican government began regulating the production of chicle through the use of cooperatives. The Agricultural Ministry stepped in an began regulating the nearly 20,000 chicleros who worked mostly independently in the forests. Fed up with the various uncontrollable variables connected to their supply of raw chicle, scientists at these companies started to come up with synthetic alternatives to the chicle harvested from the sapodilla tree. By 1950 almost no chicle could by found in American-made chewing gums. The natural forest ingredient was replaced by mixtures of petroleum-based products along with wax, polyethylene, glycerin, xylitol, styrene-butadiene rubber, polyvinyl acetate and various acids and chemical flavorings. The trees eventually healed, and the forests returned to normal with chicleros going back to producing only for local consumption. In the year 2009 a Mexican company named Chicza began producing 100% natural chicle-based chewing gum intended for mass distribution, the first such enterprise to do so in 70 years. The company is practicing sustainable harvesting and advertises with pride its profit-sharing program with the chicleros. Chicza has seen its sales increase steadily over the years and now exports its chewing gum varieties all over the world. It’s safe to say with the growing interest in organic, fair trade products that the ancient Mexican tradition of chicle will likely continue for many years to come.

The American chewing gum companies were beginning to see the handwriting on the wall by the late 1930s and early 1940s. Prices of the raw material began to soar at this time, too. During the presidency of Lázaro Cárdenas the Mexican government began regulating the production of chicle through the use of cooperatives. The Agricultural Ministry stepped in an began regulating the nearly 20,000 chicleros who worked mostly independently in the forests. Fed up with the various uncontrollable variables connected to their supply of raw chicle, scientists at these companies started to come up with synthetic alternatives to the chicle harvested from the sapodilla tree. By 1950 almost no chicle could by found in American-made chewing gums. The natural forest ingredient was replaced by mixtures of petroleum-based products along with wax, polyethylene, glycerin, xylitol, styrene-butadiene rubber, polyvinyl acetate and various acids and chemical flavorings. The trees eventually healed, and the forests returned to normal with chicleros going back to producing only for local consumption. In the year 2009 a Mexican company named Chicza began producing 100% natural chicle-based chewing gum intended for mass distribution, the first such enterprise to do so in 70 years. The company is practicing sustainable harvesting and advertises with pride its profit-sharing program with the chicleros. Chicza has seen its sales increase steadily over the years and now exports its chewing gum varieties all over the world. It’s safe to say with the growing interest in organic, fair trade products that the ancient Mexican tradition of chicle will likely continue for many years to come.

REFERENCES

MexicoLore web site, Gastro Obscura web site

Matthews, Jennifer P. Chicle: The Chewing Gum of the Americas, From the Ancient Maya to William Wrigley. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2009. We are Amazon affiliates. To buy the book on Amazon please click here: https://amzn.to/2TbtsJ2

TO BUY THE SUSTAINABLE CHICLE GUM FROM MEXICO GO HERE: https://www.amazon.com/gp/product/B08WJ4HQPX/ref=as_li_tl?ie=UTF8&camp=1789&creative=9325&creativeASIN=B08WJ4HQPX&linkCode=as2&tag=mexicounexpla-20&linkId=4a6358c5dce45f3dca3e8af77223c7fc

One thought on “The Story of Chicle”

Love your work.

Can you please do a podcast on the Chihuahua – chichi dog?