Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

The year was 1993. In the Valley of Huitzilapa near the Tequila Volcano in the Mexican state of Jalisco a construction crew suddenly stopped work on a massive building project, the Guadalajara-Tepic Freeway. Workers uncovered stone structures that made up the civic-ceremonial center of a previously unknown pre-Columbian city. Archaeologists from the Jalisco field office of Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History secured the site and began digging. What they uncovered in the central core of the site shocked them: it was the first intact burial ever discovered done in the shaft tomb style. Some were hailing it as the find of the century for Western Mexico. When the dust literally settled, archaeologists had on their hands the remains of 6 individuals and tens of thousands of artifacts in two large burial chambers. All but one of the individuals had the same spinal defects indicating possible familial ties among the deceased. The one who didn’t have that distinct defect was an older woman and most likely married into the family of the 5 others. The incredible amount of artifacts and their high quality indicated elite status. The tomb was also located in the heart of the most important part of the city which also reinforces this conclusion. The artifacts included intact ceramic figures, inlaid jewelry made of shells, jadeite ornaments, greenstone figurines and decorated pottery. Perhaps the most important find in the tomb was amate bark paper. Some of this paper was found near the cranium of one of the individuals, mostly intact. Scientific dating indicated that the paper was made sometime between 70 and 75 AD thus making it the oldest known example of paper ever found in Mesoamerica. The discovery of this tomb caused scholars to re-think their theories of status and social hierarchy in west Mexico two thousand years ago. Such an enormous cache of luxury goods found in a ceremonial burial of related individuals indicate that a royal family, or lineage of elites controlled distinct territories in the region in the early centuries AD and possibly before. Work continued at the Huitzilapa site for years with the Guadalajara-Tepic Freeway eventually re-routed away from the ruins. Archaeologists are still learning from the site, and it is not open to tourists.

The year was 1993. In the Valley of Huitzilapa near the Tequila Volcano in the Mexican state of Jalisco a construction crew suddenly stopped work on a massive building project, the Guadalajara-Tepic Freeway. Workers uncovered stone structures that made up the civic-ceremonial center of a previously unknown pre-Columbian city. Archaeologists from the Jalisco field office of Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History secured the site and began digging. What they uncovered in the central core of the site shocked them: it was the first intact burial ever discovered done in the shaft tomb style. Some were hailing it as the find of the century for Western Mexico. When the dust literally settled, archaeologists had on their hands the remains of 6 individuals and tens of thousands of artifacts in two large burial chambers. All but one of the individuals had the same spinal defects indicating possible familial ties among the deceased. The one who didn’t have that distinct defect was an older woman and most likely married into the family of the 5 others. The incredible amount of artifacts and their high quality indicated elite status. The tomb was also located in the heart of the most important part of the city which also reinforces this conclusion. The artifacts included intact ceramic figures, inlaid jewelry made of shells, jadeite ornaments, greenstone figurines and decorated pottery. Perhaps the most important find in the tomb was amate bark paper. Some of this paper was found near the cranium of one of the individuals, mostly intact. Scientific dating indicated that the paper was made sometime between 70 and 75 AD thus making it the oldest known example of paper ever found in Mesoamerica. The discovery of this tomb caused scholars to re-think their theories of status and social hierarchy in west Mexico two thousand years ago. Such an enormous cache of luxury goods found in a ceremonial burial of related individuals indicate that a royal family, or lineage of elites controlled distinct territories in the region in the early centuries AD and possibly before. Work continued at the Huitzilapa site for years with the Guadalajara-Tepic Freeway eventually re-routed away from the ruins. Archaeologists are still learning from the site, and it is not open to tourists.

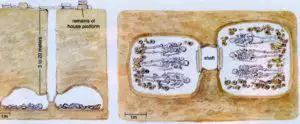

So, what is a shaft tomb? Picture a water well dug into the ground ranging from 8 to 60 feet deep and at the bottom of the well one or more chambers about the size of bedrooms in a modern house. Inside the chambers are the burials of individuals of higher social status accompanied by funerary offerings and luxury goods. Shaft tombs are usually found under or alongside important buildings. In Mexico, shaft tombs were used primarily in the western part of the country in ancient times, and they are found in the modern Mexican states of Nayarit, Jalisco and Colima. The tombs, labeled generically by researchers as being part of “The Western Mexico Shaft Tomb Tradition” cross cultural and geographical boundaries and date from about 300 BC to about 300 AD. There is little agreement on the beginning and end dates of this tradition. As some shaft tombs exist in west-central Mexico, for many years the tradition of making shaft tombs was ascribed to the Purépecha or Tarascan people. This is not the case as the practice of making shaft tombs occurs much earlier than the Tarascan civilization. There are a few other parts of the world where shaft tombs were also made, notably, in pre-Roman northern Italy under the Etruscans, in ancient Egypt and in northern South America. Some researchers have tried to make a link between the Western Mexico Shaft Tomb Tradition and the similar practice found in the archaeological records of modern-day Colombia. Most researchers in mainstream archaeology seem to believe that there was no contact between this area and Mexico, even though it has been proven that metallurgy came to Mexico from northwestern South America. Researchers note that the tombs found in South American were made centuries after the height of shaft-tomb making in Mexico, and would indicate that some sort of contact occurred going back from Mexico to South America after metallurgy was introduced to Mexico. Some scholars claim there is no evidence for back-and-forth contact between the two places. As there is a lot to untangle with the Western Mexico Shaft Tomb Tradition, there is a lot of disagreement among researchers.

So, what is a shaft tomb? Picture a water well dug into the ground ranging from 8 to 60 feet deep and at the bottom of the well one or more chambers about the size of bedrooms in a modern house. Inside the chambers are the burials of individuals of higher social status accompanied by funerary offerings and luxury goods. Shaft tombs are usually found under or alongside important buildings. In Mexico, shaft tombs were used primarily in the western part of the country in ancient times, and they are found in the modern Mexican states of Nayarit, Jalisco and Colima. The tombs, labeled generically by researchers as being part of “The Western Mexico Shaft Tomb Tradition” cross cultural and geographical boundaries and date from about 300 BC to about 300 AD. There is little agreement on the beginning and end dates of this tradition. As some shaft tombs exist in west-central Mexico, for many years the tradition of making shaft tombs was ascribed to the Purépecha or Tarascan people. This is not the case as the practice of making shaft tombs occurs much earlier than the Tarascan civilization. There are a few other parts of the world where shaft tombs were also made, notably, in pre-Roman northern Italy under the Etruscans, in ancient Egypt and in northern South America. Some researchers have tried to make a link between the Western Mexico Shaft Tomb Tradition and the similar practice found in the archaeological records of modern-day Colombia. Most researchers in mainstream archaeology seem to believe that there was no contact between this area and Mexico, even though it has been proven that metallurgy came to Mexico from northwestern South America. Researchers note that the tombs found in South American were made centuries after the height of shaft-tomb making in Mexico, and would indicate that some sort of contact occurred going back from Mexico to South America after metallurgy was introduced to Mexico. Some scholars claim there is no evidence for back-and-forth contact between the two places. As there is a lot to untangle with the Western Mexico Shaft Tomb Tradition, there is a lot of disagreement among researchers.

Since the Western Mexico Shaft Tomb Tradition seems to cross cultural, geographical and temporal boundaries, researchers categorize grave goods found in the tombs by style rather than by culture. Most of the tombs were looted in the early part of the 20th Century to supply the demand of collectors, both in Mexico and abroad. Famous Mexican artists Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo were avid collectors of clay shaft tomb figurines and are often pictured among pieces of their vast collections stored at their two Mexico City homes. Many researchers blame the famous artists for making the collecting of these pieces more popular among an international crowd and thus indirectly fueling the relentless looting and destruction of archaeological sites to meet the demands of these collectors. The thousands of looted shaft tomb figures are an archaeological treasure trove, but because they were stolen they cannot be tied to specific sites or time periods. The ceramics and other goods found in the tombs are not for ordinary everyday use and are found nowhere else, which indicates that the artists producing them produced them exclusively for the elites to be used in burials.

Since the Western Mexico Shaft Tomb Tradition seems to cross cultural, geographical and temporal boundaries, researchers categorize grave goods found in the tombs by style rather than by culture. Most of the tombs were looted in the early part of the 20th Century to supply the demand of collectors, both in Mexico and abroad. Famous Mexican artists Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo were avid collectors of clay shaft tomb figurines and are often pictured among pieces of their vast collections stored at their two Mexico City homes. Many researchers blame the famous artists for making the collecting of these pieces more popular among an international crowd and thus indirectly fueling the relentless looting and destruction of archaeological sites to meet the demands of these collectors. The thousands of looted shaft tomb figures are an archaeological treasure trove, but because they were stolen they cannot be tied to specific sites or time periods. The ceramics and other goods found in the tombs are not for ordinary everyday use and are found nowhere else, which indicates that the artists producing them produced them exclusively for the elites to be used in burials.

The clay figurines found in the tombs are delightful to collectors and folk art aficionados and usually come in several forms: Singular human figures, married couples, groups of humans engaging in various activities – art appreciation types call these “tableaus” – and a variety of animals, specifically domestic dogs. Researchers have identified some seven styles of figurines found in the shaft tombs and as with everything to do with this tradition there is little agreement on what constitutes which style and what each style ultimately means. Some figurines are not classifiable. The El Arenal, San Sebastián, and Zacatecas styles seem problematic to define as different sources say different things about each style. The four styles that have greater agreement among art historians and archaeologists are the Chinesco, Ixtlan del Rio, Colima and Ameca styles. The Chinesco or Chinesca style was so named by art dealers because of their human figurines supposed East Asian appearance. The Chinesco style is further divided into subgroups by those who want to confuse novices even more. The figurines of this style look very Olmec. Human representations usually have the reclining postures, slanted eyes and chubby thighs that hint of an influence a few hundred miles to the east. As the Western Mexico Shaft Tomb Tradition developed immediately after the decline of the Olmecs, there could be some influence from the Gulf Coast here. The Ixtlan del Rio style is characterized by human figurines having squared off bodies, skinny limbs and  grimacing faces. This style is seen by collectors as more comical. Human heads are often covered in piercings to an exaggerated degree. The Ixtlan del Rio style is so called after an archaeological site of the same name in southern Nayarit where most of these figurines were suspected to have been made. The Colima style of shaft tomb figurines are characterized by smooth and rounded surfaces and a red-slip method of ceramic production. The Colima style is known for its animal figurines, especially dogs, that are chubby and have happy expressions. Some researchers believe that in this aspect of the tomb tradition the dogs were used as symbolic guides to help the deceased cross over into the afterlife. The human figures in the Colima style are characterized by a toned-down and calmer style. Although rounded and somewhat bulbous, the human figurines are considered less “comical” or “whimsical” by art historians and collectors. The Colima style is the most common style coming out of the shaft tomb tradition that is duplicated by modern-day arts and crafts makers. The typical Colima “chubby dog” knock-off can be found in curio shops in tourist areas from Tijuana to Playa del Carmen. The final style, the Ameca, has within it some interesting human representations. Eyes are bulging and have curious rims around them. Mouths are wide but the noses are thin and aquiline, almost European-looking. Human figurines done in the Ameca style often wear strange headgear that look like anything from turbans to dunce caps. These figurines almost always have fingernails, which is a detail not found in the other styles. The Ameca tradition is generally attributed to Jalisco, but this is an educated guess based on fragments of figurines found in already looted tombs and anecdotal evidence from early collectors and some of the grave robbers themselves. There are many curious figurines found across styles. These include male figures with horns on their foreheads thought to be shamans and small representations of houses or household scenes. Some researchers theorize that the clay house scenes were placed in the tombs to give the dead comfort by reminding those who have passed of their earthly homes. Also across styles are the clay “circles of friends,” the human figures either standing or dancing with arms around each other. Like the Colima dogs, these human circles are often reproduced by modern Mexican crafters.

grimacing faces. This style is seen by collectors as more comical. Human heads are often covered in piercings to an exaggerated degree. The Ixtlan del Rio style is so called after an archaeological site of the same name in southern Nayarit where most of these figurines were suspected to have been made. The Colima style of shaft tomb figurines are characterized by smooth and rounded surfaces and a red-slip method of ceramic production. The Colima style is known for its animal figurines, especially dogs, that are chubby and have happy expressions. Some researchers believe that in this aspect of the tomb tradition the dogs were used as symbolic guides to help the deceased cross over into the afterlife. The human figures in the Colima style are characterized by a toned-down and calmer style. Although rounded and somewhat bulbous, the human figurines are considered less “comical” or “whimsical” by art historians and collectors. The Colima style is the most common style coming out of the shaft tomb tradition that is duplicated by modern-day arts and crafts makers. The typical Colima “chubby dog” knock-off can be found in curio shops in tourist areas from Tijuana to Playa del Carmen. The final style, the Ameca, has within it some interesting human representations. Eyes are bulging and have curious rims around them. Mouths are wide but the noses are thin and aquiline, almost European-looking. Human figurines done in the Ameca style often wear strange headgear that look like anything from turbans to dunce caps. These figurines almost always have fingernails, which is a detail not found in the other styles. The Ameca tradition is generally attributed to Jalisco, but this is an educated guess based on fragments of figurines found in already looted tombs and anecdotal evidence from early collectors and some of the grave robbers themselves. There are many curious figurines found across styles. These include male figures with horns on their foreheads thought to be shamans and small representations of houses or household scenes. Some researchers theorize that the clay house scenes were placed in the tombs to give the dead comfort by reminding those who have passed of their earthly homes. Also across styles are the clay “circles of friends,” the human figures either standing or dancing with arms around each other. Like the Colima dogs, these human circles are often reproduced by modern Mexican crafters.

With the massive looting of the tombs complicating further research, archaeologist are hopeful that there are still intact shaft tombs in western Mexico waiting to be found. Besides the 1993 discovery in Huitzilapa, Jalisco with the building of the freeway, there has been one other discovery of an undisturbed burial of the Western Mexican Shaft Tomb Tradition. This one was discovered in the state of Colima near the Colima Volcano at a place called Mina de Peña in the year 2014. The tomb was sealed off by 3 stone corn-grinding stones called metates, which is an important detail that would not have been known from a looted tomb. The site, which is still kept secret, provided a great wealth of figurines done in the Colima tradition along with the remains of several individuals, including two infants. DNA tests later confirmed that everyone buried in that shaft tomb was related to each other. The tomb yielded hundreds of pieces of pottery, figurines and other artifacts. Perhaps the most curious among the pieces found at this tomb was an intact 2-foot-tall figure of either a shaman or warrior holding a spear and with a serious expression on his face. He was surrounded by the characteristic dog figures. As this figure was found near the tomb’s entrance, some researchers theorize that he served as a guardian. The looters have left the tomb alone for almost 2,000 years, so perhaps there is something to this. With more tombs yet to be discovered, the final chapter on the mysterious shaft tombs of western Mexico is far from being written.

With the massive looting of the tombs complicating further research, archaeologist are hopeful that there are still intact shaft tombs in western Mexico waiting to be found. Besides the 1993 discovery in Huitzilapa, Jalisco with the building of the freeway, there has been one other discovery of an undisturbed burial of the Western Mexican Shaft Tomb Tradition. This one was discovered in the state of Colima near the Colima Volcano at a place called Mina de Peña in the year 2014. The tomb was sealed off by 3 stone corn-grinding stones called metates, which is an important detail that would not have been known from a looted tomb. The site, which is still kept secret, provided a great wealth of figurines done in the Colima tradition along with the remains of several individuals, including two infants. DNA tests later confirmed that everyone buried in that shaft tomb was related to each other. The tomb yielded hundreds of pieces of pottery, figurines and other artifacts. Perhaps the most curious among the pieces found at this tomb was an intact 2-foot-tall figure of either a shaman or warrior holding a spear and with a serious expression on his face. He was surrounded by the characteristic dog figures. As this figure was found near the tomb’s entrance, some researchers theorize that he served as a guardian. The looters have left the tomb alone for almost 2,000 years, so perhaps there is something to this. With more tombs yet to be discovered, the final chapter on the mysterious shaft tombs of western Mexico is far from being written.

REFERENCES

INAH Web site (in Spanish)