Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

Mexico Unexplained will return once again to the diaries of John Lloyd Stephens written in October and November of 1841. The thirty-five-year-old New-Jersey-born Stephens had recently arrived in Mérida, the capital city of Yucatán. Two years earlier, American President Martin van Buren appointed Stephens to be the Special US Ambassador to the Federal Republic of Central America. To make a long story short, Stephens left Central America when the government collapsed, and in October of 1841 he would return to the region, this time exploring Mexican territory, using Mérida as his jumping-off point. While organizing the expedition to go deeper in the interior, Stephens spent time in the Yucatán capital taking in the local culture. In his notes that would later become a book called Incidents of Travel in Yucatan, Stephens describes a curious activity in the marketplace: cacao beans used as currency, as a universally accepted median of exchange to buy and sell goods. In his book, Stephens writes:

Mexico Unexplained will return once again to the diaries of John Lloyd Stephens written in October and November of 1841. The thirty-five-year-old New-Jersey-born Stephens had recently arrived in Mérida, the capital city of Yucatán. Two years earlier, American President Martin van Buren appointed Stephens to be the Special US Ambassador to the Federal Republic of Central America. To make a long story short, Stephens left Central America when the government collapsed, and in October of 1841 he would return to the region, this time exploring Mexican territory, using Mérida as his jumping-off point. While organizing the expedition to go deeper in the interior, Stephens spent time in the Yucatán capital taking in the local culture. In his notes that would later become a book called Incidents of Travel in Yucatan, Stephens describes a curious activity in the marketplace: cacao beans used as currency, as a universally accepted median of exchange to buy and sell goods. In his book, Stephens writes:

“What I had heard of, but had not seen before, that grains of cacao circulated among the Indians as money. Every merchant or vendor of eatables, the most of whom were women, had on the table a pile of these grains which they were constantly counting and exchanging with the Indians. There is no copper money in Yucatán nor any coin whatever under a medio, or six and a quarter cents, and this deficiency is supplied by these grains of cacao. The medio is divided into 20 parts, generally of five grains each, but the number is increased or decreased according to the quantity of the article in the market, and its real value as the earnings of the Indians are small and the articles they purchase are the mere necessities of life which are very cheap, these grains of cacao, or fractional parts of a medio, are the coin in most common use among them. The currency has always a real value and is regulated by the quantity of cacao in the market, and the only inconvenience, economically speaking, that it has, is the loss of a certain public wealth by the destruction of the cacao as in the case of banknotes. But these grains had an interest independent of all questions of political economy for they indicate or illustrate a page in the history of this unknown and mysterious people. When the Spaniards first made their way into the interior of Yucatán they found no circulating medium, either of gold or silver or any other species of metal, but only grains of cacao; and it seemed the stranger circumstance that while the manners and customs of the Indians have undergone an immense change, while their cities have been destroyed, their religion dishonored their princes swept away and their whole government modified by foreign laws, no experiment has yet been made upon their currency.”

First off, we can eliminate some confusion and firmly define terms. Is “cacao” the same as “cocoa”? Well, the question is not so easy to answer. “Cacao” refers to the bean of the cacao tree, known scientifically as Theobroma cacao. The Greek words “Theo” and “broma” combine to make the first part of the name of the tree, and literally mean “food of the gods.” Cacao can also refer to unprocessed and minimally processed aspects of the cacao bean, such as nibs and powder. Cocoa is a more processed product of the cacao bean, usually made into a powder with dairy products and sugar added to the mix. Cocoa can also refer to a sweet beverage also called “hot chocolate.” Chocolate, a cacao-based product in the form of candy, is a relatively new invention and came about only a few hundred years ago in Europe. Cultivation and harvesting of the cacao tree dates back a lot farther in time, though, and the story begins in the tropical lowlands of Mexico and Central America.

First off, we can eliminate some confusion and firmly define terms. Is “cacao” the same as “cocoa”? Well, the question is not so easy to answer. “Cacao” refers to the bean of the cacao tree, known scientifically as Theobroma cacao. The Greek words “Theo” and “broma” combine to make the first part of the name of the tree, and literally mean “food of the gods.” Cacao can also refer to unprocessed and minimally processed aspects of the cacao bean, such as nibs and powder. Cocoa is a more processed product of the cacao bean, usually made into a powder with dairy products and sugar added to the mix. Cocoa can also refer to a sweet beverage also called “hot chocolate.” Chocolate, a cacao-based product in the form of candy, is a relatively new invention and came about only a few hundred years ago in Europe. Cultivation and harvesting of the cacao tree dates back a lot farther in time, though, and the story begins in the tropical lowlands of Mexico and Central America.

The cacao tree is a leafy evergreen and stands about twelve to twenty-six feet tall. It is native to the jungles of Mexico and Central America as well as the Amazon Basin in South America. The tree grows as what botanists call an understory plant, meaning, it grows below the forest canopy. Midges and other small insects pollinate the flowers of the cacao tree, and the smaller insects thrive in tropical environments with a wide variety of plants in various states of decay around them. This is why cacao trees do better when planted and cultivated in already established forests rather than in large commercial plantations. They need an entire native ecosystem to thrive. The flowers are produced directly on the trunk of the tree and on older branches. Although the flowers only measure about a half inch across, the fruit they produce develop into a pod that is roughly the size of an American football, about 6 to 12 inches long and 3 to 5 inches across. The fruit pod ripens to a bright yellow or orange and contains about 50 or so seeds, known as the cacao beans. These beans are embedded in a sweet white pulp that is attractive to animals such as birds and monkeys who eat the pulp and thus disperse the seeds. Sometimes the pulp part of the cacao pod is fermented into an alcoholic beverage. The cacao bean contains active stimulants including theobromine, which is very similar to caffeine. Although native to the Americas, cacao is produced commercially throughout the world in tropical places with some 25 million acres under cultivation, mostly by small farmers. In 2021, Ivory Coast in western Africa is the world’s largest producer of cacao.

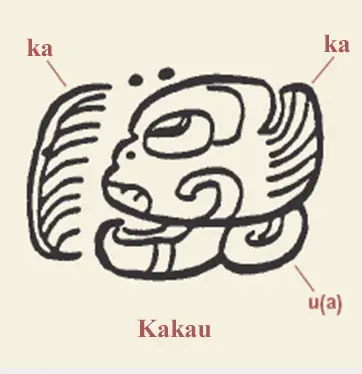

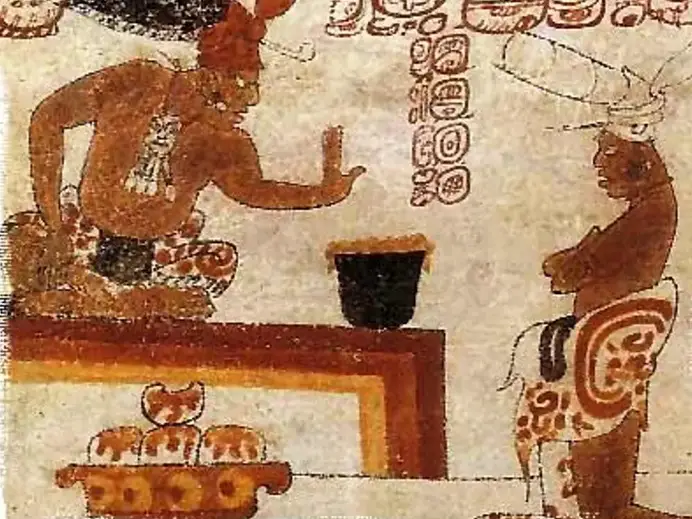

The ancient Mexicans harvested the cacao beans to turn it into a drink served hot and foamy. Ceramic vessels used to store chocolate as a drink have been found at archaeological sites in the Gulf Coast of Mexico that predate the Olmecs going back to 1750 BC. A recent find of a chocolate vessel on the Pacific coast of the modern Mexican state of Chiapas from the Mokaya culture may date back a century and a half earlier. In the year 2018, a scientist analyzing the genetic make up of various cacao trees traced back their ancestry to a single domestication event that happened around 1600 BC somewhere in Central America, most likely in the area that is now known as Soconusco on the Pacific coast. The Olmecs and later the Maya used cacao in making a hot frothy drink as a standard to be used in ceremonies of the political and religious elites. Chocolate containers are found in Maya royal burials throughout Mexico and Central America. In Maya art, notably in murals and on stone carvings, we see chocolate being served at royal courts and during specific celebrations. The earliest written reference to chocolate is found at a site dating to 450 AD. The written glyph for chocolate is syllabic and the syllables read “ca-ca-aw” which is almost the same way as we pronounce the name of the plant and the bean today. We see in the artwork how important the foam was on the top of the chocolate drink. There are many examples of depictions of people pouring chocolate from a standing position from a larger vessel to a smaller one placed on the floor, usually a ceramic cup or gourd. This was their way to get a frothy head to the drink that was scooped off the top with a bone or turtle shell spoon and thoroughly enjoyed. As the preparation of the chocolate – starting with the cacao bean – is highly complex, it is an utter mystery how the ancients learned how to prepare this exotic and complicated drink. The ancient Maya would tell you that the knowledge came from the god Ek Chuaj, also known by its older classification as God M as seen on the Dresden and Madrid Codices. Ek Chuaj was not only the Maya god associated with cacao, he was also the patron of merchants. Perhaps the dual duties the god served was due to the fact that cacao was also used as a currency and was an important trade good. Ek Chuaj is closely associated with what archaeologists call God L known as a grandfather god among the Maya who is often depicted surrounded by cacao pods. Although a gift from the gods and used in some religious ceremonies, the powerful stimulant brewed into the chocolate drink was never used for shamanistic purposes. As an elite drink among the Maya, it was often blended with vanilla, chile powder, corn and honey. Commoners were not permitted to drink chocolate, and this would be the case throughout Mexico all the way up until the Spanish Conquest.

The ancient Mexicans harvested the cacao beans to turn it into a drink served hot and foamy. Ceramic vessels used to store chocolate as a drink have been found at archaeological sites in the Gulf Coast of Mexico that predate the Olmecs going back to 1750 BC. A recent find of a chocolate vessel on the Pacific coast of the modern Mexican state of Chiapas from the Mokaya culture may date back a century and a half earlier. In the year 2018, a scientist analyzing the genetic make up of various cacao trees traced back their ancestry to a single domestication event that happened around 1600 BC somewhere in Central America, most likely in the area that is now known as Soconusco on the Pacific coast. The Olmecs and later the Maya used cacao in making a hot frothy drink as a standard to be used in ceremonies of the political and religious elites. Chocolate containers are found in Maya royal burials throughout Mexico and Central America. In Maya art, notably in murals and on stone carvings, we see chocolate being served at royal courts and during specific celebrations. The earliest written reference to chocolate is found at a site dating to 450 AD. The written glyph for chocolate is syllabic and the syllables read “ca-ca-aw” which is almost the same way as we pronounce the name of the plant and the bean today. We see in the artwork how important the foam was on the top of the chocolate drink. There are many examples of depictions of people pouring chocolate from a standing position from a larger vessel to a smaller one placed on the floor, usually a ceramic cup or gourd. This was their way to get a frothy head to the drink that was scooped off the top with a bone or turtle shell spoon and thoroughly enjoyed. As the preparation of the chocolate – starting with the cacao bean – is highly complex, it is an utter mystery how the ancients learned how to prepare this exotic and complicated drink. The ancient Maya would tell you that the knowledge came from the god Ek Chuaj, also known by its older classification as God M as seen on the Dresden and Madrid Codices. Ek Chuaj was not only the Maya god associated with cacao, he was also the patron of merchants. Perhaps the dual duties the god served was due to the fact that cacao was also used as a currency and was an important trade good. Ek Chuaj is closely associated with what archaeologists call God L known as a grandfather god among the Maya who is often depicted surrounded by cacao pods. Although a gift from the gods and used in some religious ceremonies, the powerful stimulant brewed into the chocolate drink was never used for shamanistic purposes. As an elite drink among the Maya, it was often blended with vanilla, chile powder, corn and honey. Commoners were not permitted to drink chocolate, and this would be the case throughout Mexico all the way up until the Spanish Conquest.

Outside of the Maya area, cacao was an important luxury good for those cultures that had a hard time accessing it. In El Tajín in the modern-day Mexican state of Veracruz there is a stone carving showing a cacao tree as an object of worship, and this probably dates to around 500 AD. The city of El Tajín dominated the region and had a large trade network that connected it with all the major civilizations at the time. For more information about El Tajín, please see Mexico Unexplained episode number 138: https://mexicounexplained.com/el-tajin-ancient-city-of-mystery/ Contemporary with El Tajín was the central Mexican powerhouse of Teotihuacán. At this massive ancient city cacao was also used much as it had been in the Maya area: made into an elite drink reserved for a few and used as a medium of exchange in the markets. Teotihuacán may have had direct control over or had a strong alliance with the region called Xoconochco, now referred to as Soconusco, located on the Pacific coast straddling the modern-day borders of Mexico and Guatemala. In this region, even to this day, the very best cacao is produced, called the criollo variety. As that special variety of cacao was highly prized, so was the territory, and many centuries after the fall of Teotihuacán, the Aztecs would control Xoconochco, located some 550 miles from their capital at Tenochtitlán. For more information about this fascinating region, please see Mexico Unexplained episode 162 called “Xoconochco, the Remotest Aztec Province” https://mexicounexplained.com/xoconochco-the-remotest-aztec-province/

We know how important cacao was to the Aztecs from their written records and also from contemporary Spanish accounts that recorded a living and breathing civilization at its height. The Aztecs were new to the custom of drinking chocolate, as they arrived in central Mexico in the mid-1300s. As in previous civilizations, chocolate drinking was reserved for the elites and for special occasions. Women in the Aztec realm were prohibited from drinking it. According to some Spanish chroniclers, many Aztecs had an ambivalent feeling about chocolate. Some thought it was a foreign practice that was effete and made them soft. The cacao beans, however, played a more important role in the daily lives of the Aztecs. Like the Maya, they used the beans as currency. In parts of the Aztec Empire where the cacao tree grew, the people there were taxed with the balance to be paid in sacks of the important bean. So, in a sense, in ancient Mexico money did grow on trees. Aztec taxation officials had to be wary of counterfeit beans. Archaeologists have found replica cacao beans carved out of wood, used not only to defraud the tax authorities but also passed in the lesser-known marketplaces to cheat even the smallest sellers of their wares.

We know how important cacao was to the Aztecs from their written records and also from contemporary Spanish accounts that recorded a living and breathing civilization at its height. The Aztecs were new to the custom of drinking chocolate, as they arrived in central Mexico in the mid-1300s. As in previous civilizations, chocolate drinking was reserved for the elites and for special occasions. Women in the Aztec realm were prohibited from drinking it. According to some Spanish chroniclers, many Aztecs had an ambivalent feeling about chocolate. Some thought it was a foreign practice that was effete and made them soft. The cacao beans, however, played a more important role in the daily lives of the Aztecs. Like the Maya, they used the beans as currency. In parts of the Aztec Empire where the cacao tree grew, the people there were taxed with the balance to be paid in sacks of the important bean. So, in a sense, in ancient Mexico money did grow on trees. Aztec taxation officials had to be wary of counterfeit beans. Archaeologists have found replica cacao beans carved out of wood, used not only to defraud the tax authorities but also passed in the lesser-known marketplaces to cheat even the smallest sellers of their wares.

The Spanish did not take to drinking chocolate at first because the taste was so bitter. Ironically, the drink that was once off limits to women, became a popular drink among female members of the upper classes of New Spain. Wealthy Spanish women in Mexico would combine the drink with sugar and cinnamon. As this hybrid beverage made its way back to Spain, it became popular at the royal court in Madrid. Soon, it became a luxury drink of the upper classes throughout Europe. Eventually, more things were added to chocolate and more things were extracted from it. By the time the Swiss got a hold of it, they were adding milk to it, and in the 1800s many Europeans were turning this drink into a hard candy confection. The modern-day chocolate so popular throughout the world is a concoction comprised mostly of sugar, milk and synthetic oils with only about 15% of it made up of genuine cacao extracts. Because of the well-recognized health benefits of the cacao bean, interest is growing in the original chocolate drink brewed by the ancient Mexicans as well as various natural products associated with cacao. As a gift to humanity, the ancients have left behind an important legacy in the harvesting and cultivation of this most important forest product.

REFERENCES

Coe, Sophie D. and Michael D. Coe. The True History of Chocolate. New York: Thames and Hudson, 2013. We are Amazon affiliates. Buy the book on Amazon here: https://amzn.to/2Yu7m7m