Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

Traveling through northern Mexico in 1846, British writer George Ruxton would say this about the area in his book, Adventures in Mexico and the Rocky Mountains:

Traveling through northern Mexico in 1846, British writer George Ruxton would say this about the area in his book, Adventures in Mexico and the Rocky Mountains:

“They [the Comanche] are now overrunning the whole departments of Durango and Chihuahua, have cut off all communication, and defeated…the regular troops sent against them. Upwards of ten thousand head of horses and mules have already been carried off, and scarcely has a hacienda or rancho on the frontier been unvisited, and everywhere the people have been killed or captured. The roads are impassible, all traffic is stopped, the ranchos barricaded, and the inhabitants afraid to venture out of their doors.”

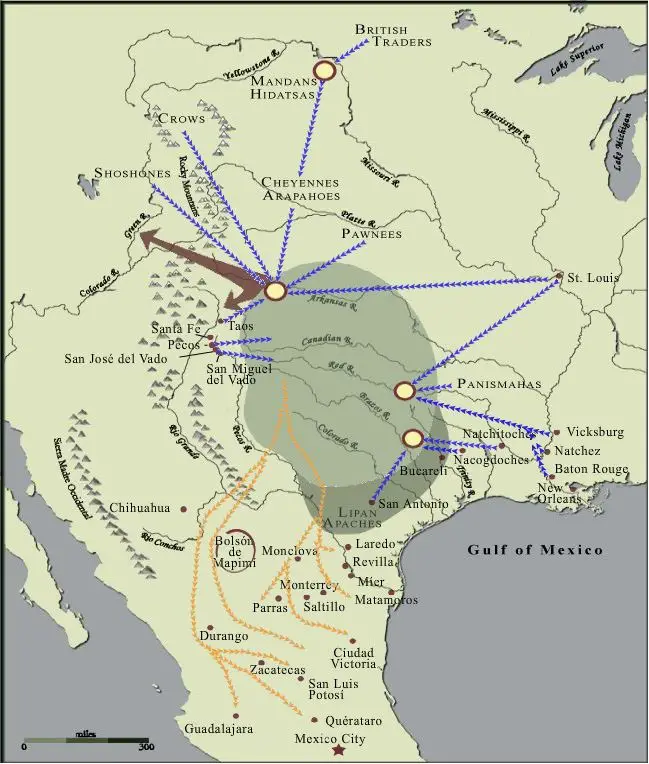

Mexico Unexplained episode number 212 https://mexicounexplained.com/the-comanche-wars-1821-1870/ examined what historians call the Comanche Wars, which took place between various factions of the Mexican government and raiding parties of the Comanche of the central and southern plains of North America. The wars effectively ended with the Mexican War, also known as the Mexican-American War, which resulted in Mexico surrendering more than half its territory under the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo of 1848. Article XI of the treaty stated that the United States would end all Indian raids into Mexican territory from the US and would compensate Mexico and private Mexican citizens for damages done by raiding parties that did cross the Rio Grande into Mexican territory. The US found this article nearly impossible to uphold and wound up paying over 350 claims made through Article XI. The US involvement in halting the practice of long-distance raiding done by the Apache and Comanche did ultimately have an effect, and by 1870 there were no more raids. The Comanche Wars with Mexico from 1821 to 1870 had a devastating and long-lasting effect. Their early origins in the far northern fringes of the Spanish Empire in North America are seldom examined, though, and date back to the end of the 1600s.

The first recorded Comanche raid happened sometime in the middle of the first decade of the 1700s and it was not on a Spanish settlement. As one author put it, “the Comanche suddenly appeared like a thunderbolt out of the northern mountains.” They raided the settlements of the Jicarilla Apache northeast of Taos located in what is now the northern part of the US state of New Mexico. The Comanche had migrated from the northern plains in search of new territory, for a time setting up camps in the San Luis Valley near the headwaters of the Rio Grande in what is now Colorado. This was the traditional homeland of the Utes, who the Comanche saw as cousins. The two indigenous groups coexisted peacefully in this mountainous domain. During the late 1600s the Comanche had acquired horses, both wild and domesticated, and became swift and adept riders. By the early 1700s the Comanche were expanding south and the plains on which the Jicarilla Apache called home were filled with game and proved very inviting to them.

The first recorded Comanche raid happened sometime in the middle of the first decade of the 1700s and it was not on a Spanish settlement. As one author put it, “the Comanche suddenly appeared like a thunderbolt out of the northern mountains.” They raided the settlements of the Jicarilla Apache northeast of Taos located in what is now the northern part of the US state of New Mexico. The Comanche had migrated from the northern plains in search of new territory, for a time setting up camps in the San Luis Valley near the headwaters of the Rio Grande in what is now Colorado. This was the traditional homeland of the Utes, who the Comanche saw as cousins. The two indigenous groups coexisted peacefully in this mountainous domain. During the late 1600s the Comanche had acquired horses, both wild and domesticated, and became swift and adept riders. By the early 1700s the Comanche were expanding south and the plains on which the Jicarilla Apache called home were filled with game and proved very inviting to them.

By 1730 the Jicarilla Apache abandoned their hunting grounds and moved south and west, leaving the plains in what is now northeastern New Mexico to the Comanche. From their camps on the lush grasslands, the Comanche mounted raids on the Spanish settlements and the indigenous Pueblos of the Rio Grande Valley. While historically at odds with one another, the Spanish and the Pueblos had to unite against a common enemy. A system of mutual support developed, and Pueblos formed militia groups to fight alongside soldiers in service of the Spanish king. Pueblos opened their villages to Spanish settlers who lost their homes to Comanche raiding parties. This sort of cooperation would have been unthinkable before the Pueblo Revolt of 1680.

New Mexico’s defenses against the Comanche consisted of two presidios of troops. One was located in Santa Fe and consisted of 80 men and the other was located in El Paso which was too far away to be of any use in the fighting against the marauding natives. These defenses were augmented by large numbers of citizen militias including the ones from the Pueblos mentioned earlier. When the Comanche stepped up their efforts in the mid-1750s, with raiding parties numbering into the hundreds, pleas from the governor of New Mexico made to the viceroy in Mexico City were met with silence or were dismissed as exaggerations. The Spanish king was distracted by troubles in Europe and by the larger menace to his North American holdings posed by the British and the French. New Mexico was neglected and the royal authorities showed more interest in reducing expenses on the northern frontier. Because of this, Comanche power was allowed to grow.

Besides direct combat in what was then termed as “total war by fire and blood,” the Spanish tried negotiating with the Comanche. Friars and government officials were sent as emissaries to some of the camps to try to get members of the nomadic tribe to settle down into towns where all their needs would be provided for them. Some Spanish government officials were known to pay large bribes to some Comanche war party leaders, and this seemed to work, at least in the short run. Another tactic the Spanish had to deal with the Comanche was to invite them to the annual “Great Taos Trade Fair,” a week-long celebration and market that took place in the fall. People of various tribes – Apache, Ute, Navajo and even Comanche – would convene in the Taos Valley to exchange buffalo jerky and hides, as well as horses, for Pueblo foodstuffs and European manufactured goods. It was a week of détente, a cessation of hostilities, where all peoples mingled. The Spanish used the Taos Fair to try to impart upon the Comanche the benefits of a more settled-down and peaceful existence. It didn’t work. In fact, in some cases the Comanche came back the week after the fair in raids to steal back the horses they had bartered away.

While the thirteen English colonies on the Eastern Seaboard were on the eve of independence in the 1770s, New Mexico was being reduced to poverty and ruin by the continued hammering away by the Comanche. Records from the era are amazing to read. For example, in July of 1774, a raiding party of over 1,000 Comanche attacked the Chama Valley and Santa Clara Pueblo, killing 7 people, wounding dozens and kidnapping 3 Spanish children. A particularly brutal time occurred from the beginning of May to the end of July 1775. A gigantic raiding party consisting of mostly Comanche and some of their Navajo and Gila Apache allies, descended upon the area near modern-day Albuquerque. During this time, 41 people were killed. 33 of them were indigenous people  from Sandia Pueblo. In these few months, many ranches and pueblos lost all their horses, making a counter-attack impossible. People then began to abandon the countryside and cluster in the few urban areas that existed in this sparsely populated area. The city of Santa Fe doubled in population as it received a steady stream of refugees from the embattled countryside. In 1776, an inspector of the New Mexico missions sent from Mexico City wrote in his report that Taos Pueblo was so fortified that, “it resembled those walled cities with bastions and towers that are described to us in the Bible.” In the same year, 1776, the governor of New Mexico, Pedro Fermin de Mendinueta sent an urgent letter to Mexico City claiming that he could not guarantee the future survival of New Mexico under its current state of siege.

from Sandia Pueblo. In these few months, many ranches and pueblos lost all their horses, making a counter-attack impossible. People then began to abandon the countryside and cluster in the few urban areas that existed in this sparsely populated area. The city of Santa Fe doubled in population as it received a steady stream of refugees from the embattled countryside. In 1776, an inspector of the New Mexico missions sent from Mexico City wrote in his report that Taos Pueblo was so fortified that, “it resembled those walled cities with bastions and towers that are described to us in the Bible.” In the same year, 1776, the governor of New Mexico, Pedro Fermin de Mendinueta sent an urgent letter to Mexico City claiming that he could not guarantee the future survival of New Mexico under its current state of siege.

The dire news reached the ears of the Spanish king who finally decided to strengthen the northern periphery of his New World dominions. The military jurisdiction in the north was reorganized and the king appointed a seasoned army officer, General Teodoro de Croix, to head the Commandancy General of the Interior Provinces. The new military commander requested and received 2,000 soldiers to help end the Comanche raids. By 1778, New Mexico had a new governor, a man named Don Juan Bautista de Anza, who had made a name for himself in California and Sonora. Together with the new military commander, de Anza hatched a plan of divide and conquer to break the stranglehold the Comanche had on New Mexico. They would negotiate with individual Comanche raiding parties and form firm alliances with them so that together with the Spanish and the Pueblos the Comanche would go after the Apache. Governor de Anza was a seasoned veteran of Indian wars fought in his native northern Sonora. He knew that if this plan would work, he would have to take the fight to the Comanche homeland instead of waiting for the Comanche to mount a massive attack on Santa Fe. One of the most formidable Comanche leaders at the time was called Chief Cuerno Verde, which means “green horn” in Spanish. His name came from the green-colored buffalo horns on his headdress. Cuerno Verde had killed hundreds of people and took many captives that were either sacrificed later, used as slaves, or sold into slavery to other plains peoples farther north and east. In August of 1779, Governor de Anza gathered together his fighting force at San Juan Pueblo and headed north into the modern-day state of Colorado to meet Cuerno Verde on his own turf. The Spaniards attacked Cuerno Verde’s camp from behind, but the leader was not there. The chief and hundreds of others had left to raid  New Mexico. The de Anza party caught up with Cuerno Verde near the Arkansas River, and outnumbered, the Comanche made their last stand by killing their own horses and using them as a barricade. In the end Cuerno Verde and his son and also all of his subchiefs died in the battle. Governor de Anza returned to Santa Fe with the great chief’s buffalo headdress with its painted green horns as a prize. While the raiding lessened a great deal, a formal peace treaty with the Comanche did not come to pass until 1786. After years of work, the Spanish got the Comanche to agree to elect a single leader to represent them. An impressive group of Comanche chiefs met with the Spaniards at Pecos Pueblo to consummate the treaty of peace. The new leader, Chief Ecueracapa was given the title of “General of the Comanche Nation,” and was presented with a staff of office, a saber, and a banner authorized by the Spanish king, in a ceremony full of pomp and colorful flourishes. Later that year, the Comanche would join the Spanish in their campaigns against the Apache. The peace held for many decades, but when Spain’s grip over New Mexico began to lessen in the early 1800s, the raiding started again. A weaker nation called Mexico found itself strapped financially and old Indian alliances crumbled in the wake of a weakened military presence in the north. By the 1820s the Comanche were back to the long-distance raids involving hundreds of warriors. Times returned to the way they were before the capture of Cuerno Verde and thus began the decades-long Comanche Wars with Mexico.

New Mexico. The de Anza party caught up with Cuerno Verde near the Arkansas River, and outnumbered, the Comanche made their last stand by killing their own horses and using them as a barricade. In the end Cuerno Verde and his son and also all of his subchiefs died in the battle. Governor de Anza returned to Santa Fe with the great chief’s buffalo headdress with its painted green horns as a prize. While the raiding lessened a great deal, a formal peace treaty with the Comanche did not come to pass until 1786. After years of work, the Spanish got the Comanche to agree to elect a single leader to represent them. An impressive group of Comanche chiefs met with the Spaniards at Pecos Pueblo to consummate the treaty of peace. The new leader, Chief Ecueracapa was given the title of “General of the Comanche Nation,” and was presented with a staff of office, a saber, and a banner authorized by the Spanish king, in a ceremony full of pomp and colorful flourishes. Later that year, the Comanche would join the Spanish in their campaigns against the Apache. The peace held for many decades, but when Spain’s grip over New Mexico began to lessen in the early 1800s, the raiding started again. A weaker nation called Mexico found itself strapped financially and old Indian alliances crumbled in the wake of a weakened military presence in the north. By the 1820s the Comanche were back to the long-distance raids involving hundreds of warriors. Times returned to the way they were before the capture of Cuerno Verde and thus began the decades-long Comanche Wars with Mexico.

REFERENCES

Simmons, Marc. New Mexico: An Interpretive History. Albuquerque: UNM Press, 1988. We are Amazon affiliates. Buy the book on Amazon here: https://amzn.to/3iqPcNe