Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

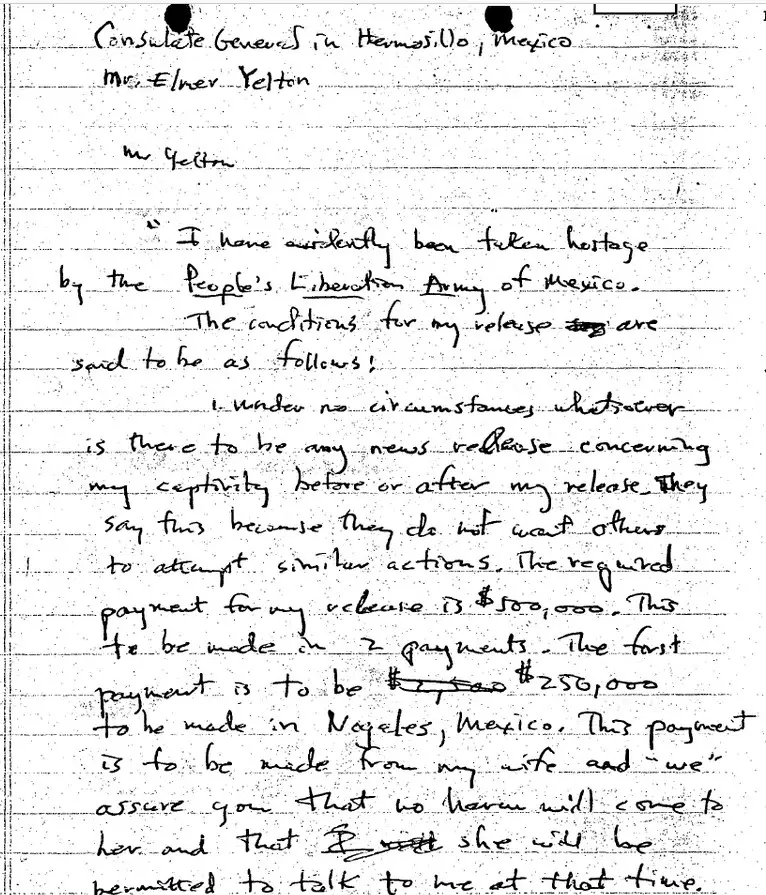

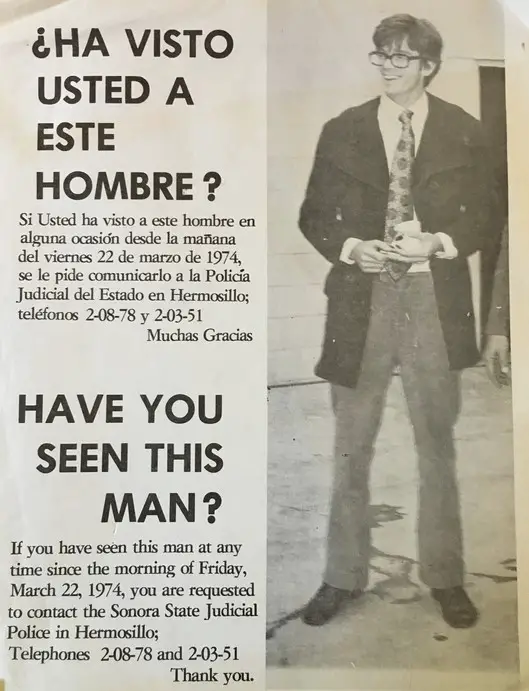

In the afternoon of March 22, 1974, Andra Patterson walked into the library of the American Consulate in Hermosillo, Sonora. She had a little time to kill before picking up her daughter Julia from school. Andra had access to the library because her husband John Patterson was stationed with the US Foreign Service in Hermosillo serving as a vice consul responsible for promoting trade between the U.S. and Mexico. On that day in March 1974 John had taken the consular truck to meet an American cattle broker who was interested in doing business with Mexican ranchers. While John’s wife Andra was leisurely perusing the books in the consulate’s library, a staff secretary asked her if she would please meet with Elmer Yelton, the consul general, in his office. Yelton told Andra that John never showed up for his meeting with the ranchers. Additionally, when the staff at the American consulate returned from lunch that day, they discovered a large envelope stuffed under the consulate door addressed to Yelton. Inside the envelope were two pages of green stationery with handwriting on them. Yelton showed the pages to Andra who verified that it was her husband’s handwriting on the papers. The note began, “I have evidently been taken hostage by the People’s Liberation Army of Mexico…” and then it listed demands. John Patterson’s ransom of half a million dollars was to be paid in two installments. Half of it was to be dropped off at the Hotel Fray Marcos in Nogales, Sonora in two days. Then, Andra was to fly to Mexico City and check into the Airport Holiday Inn where she was to await instructions on how to pay the second part of the ransom. According to the note, under no circumstances was the press to be notified of the kidnapping. If the press did run with the story, the note stated, the People’s Liberation Army of Mexico would execute 1 American official per week or one member of an official’s family per week. Later that night, the news of Patterson’s kidnapping reached President Richard Nixon who was on his way to spend the weekend at Camp David. This situation was a familiar one to Nixon; Patterson had been the 6th American diplomat to be abducted within a year. Two American diplomats in Haiti had been released because the Americans conceded to the kidnappers’ demands. Nixon took a harder stance when two US Foreign Service officials were taken at the Saudi embassy in Sudan. When hostage negotiators were en route to Africa to try to secure the release of the two diplomats, Nixon held a press conference. During the conference when he was asked about the hostage situation in Sudan he replied, “As far as the United States as a government giving in to blackmail demands, we cannot do so, and we will not do so.” That left nothing for the hostage negotiators to work with, and the two held in Sudan were executed a few hours later. That impromptu reply by Nixon at the press conference then became official US policy, and by the time the 5th kidnapping occurred, the administration had a solid stance. The 5th kidnapping happened in Mexico when a leftist group called the Armed Revolutionary Forces of the People abducted the US consul general in Guadalajara. While publicly the stance was firm on not negotiating with terrorists, Nixon used back channels to pressure Mexican officials to negotiate the consul’s safe release. This was successful and this American diplomat’s captivity only lasted 3 days. The same sort of approach would be taken to secure John Patterson’s safe release.

In the afternoon of March 22, 1974, Andra Patterson walked into the library of the American Consulate in Hermosillo, Sonora. She had a little time to kill before picking up her daughter Julia from school. Andra had access to the library because her husband John Patterson was stationed with the US Foreign Service in Hermosillo serving as a vice consul responsible for promoting trade between the U.S. and Mexico. On that day in March 1974 John had taken the consular truck to meet an American cattle broker who was interested in doing business with Mexican ranchers. While John’s wife Andra was leisurely perusing the books in the consulate’s library, a staff secretary asked her if she would please meet with Elmer Yelton, the consul general, in his office. Yelton told Andra that John never showed up for his meeting with the ranchers. Additionally, when the staff at the American consulate returned from lunch that day, they discovered a large envelope stuffed under the consulate door addressed to Yelton. Inside the envelope were two pages of green stationery with handwriting on them. Yelton showed the pages to Andra who verified that it was her husband’s handwriting on the papers. The note began, “I have evidently been taken hostage by the People’s Liberation Army of Mexico…” and then it listed demands. John Patterson’s ransom of half a million dollars was to be paid in two installments. Half of it was to be dropped off at the Hotel Fray Marcos in Nogales, Sonora in two days. Then, Andra was to fly to Mexico City and check into the Airport Holiday Inn where she was to await instructions on how to pay the second part of the ransom. According to the note, under no circumstances was the press to be notified of the kidnapping. If the press did run with the story, the note stated, the People’s Liberation Army of Mexico would execute 1 American official per week or one member of an official’s family per week. Later that night, the news of Patterson’s kidnapping reached President Richard Nixon who was on his way to spend the weekend at Camp David. This situation was a familiar one to Nixon; Patterson had been the 6th American diplomat to be abducted within a year. Two American diplomats in Haiti had been released because the Americans conceded to the kidnappers’ demands. Nixon took a harder stance when two US Foreign Service officials were taken at the Saudi embassy in Sudan. When hostage negotiators were en route to Africa to try to secure the release of the two diplomats, Nixon held a press conference. During the conference when he was asked about the hostage situation in Sudan he replied, “As far as the United States as a government giving in to blackmail demands, we cannot do so, and we will not do so.” That left nothing for the hostage negotiators to work with, and the two held in Sudan were executed a few hours later. That impromptu reply by Nixon at the press conference then became official US policy, and by the time the 5th kidnapping occurred, the administration had a solid stance. The 5th kidnapping happened in Mexico when a leftist group called the Armed Revolutionary Forces of the People abducted the US consul general in Guadalajara. While publicly the stance was firm on not negotiating with terrorists, Nixon used back channels to pressure Mexican officials to negotiate the consul’s safe release. This was successful and this American diplomat’s captivity only lasted 3 days. The same sort of approach would be taken to secure John Patterson’s safe release.

With no official help from the US government to raise the money to pay the ransom, Andra Patterson went to her mother for help. Andra’s mother secured a $250,000 loan from a grocery store heiress who was a friend of the family. With the money now available, Andra went to Arizona to pick it up with plenty of time to cross the border to make the drop in Nogales, Sonora as per the demands of the People’s Liberation Army of Mexico. She did not go alone. Two State Department veterans accompanied Andra on the flight from Hermosillo to Tucson and then overland from Tucson, to Nogales, Arizona. At a motel on the American side, they waited for a courier to deliver the ransom money from Phoenix. Meanwhile, the FBI sent dozens of agents along, and with the permission of the Mexican government, they would stake out the Fray Marcos hotel in hopes of identifying and tracking the person who was to pick up the cash. There were some people in the FBI who believed that whoever was going to show up at the Nogales hotel to collect the ransom had ties to John and Andra Patterson and that the whole kidnapping was faked by the Pattersons. The courier from Phoenix arrived with a dozen or so Girl Scout cookie boxes stuffed with $20 and $50 bills and loaded them into a trunk of a car. Andra and her State Department bodyguards drove across the border to the hotel which was less than a mile from the international line. Andra waited there and no one showed up. US government officials suggested she drive back to Hermosillo, which she did.

With no official help from the US government to raise the money to pay the ransom, Andra Patterson went to her mother for help. Andra’s mother secured a $250,000 loan from a grocery store heiress who was a friend of the family. With the money now available, Andra went to Arizona to pick it up with plenty of time to cross the border to make the drop in Nogales, Sonora as per the demands of the People’s Liberation Army of Mexico. She did not go alone. Two State Department veterans accompanied Andra on the flight from Hermosillo to Tucson and then overland from Tucson, to Nogales, Arizona. At a motel on the American side, they waited for a courier to deliver the ransom money from Phoenix. Meanwhile, the FBI sent dozens of agents along, and with the permission of the Mexican government, they would stake out the Fray Marcos hotel in hopes of identifying and tracking the person who was to pick up the cash. There were some people in the FBI who believed that whoever was going to show up at the Nogales hotel to collect the ransom had ties to John and Andra Patterson and that the whole kidnapping was faked by the Pattersons. The courier from Phoenix arrived with a dozen or so Girl Scout cookie boxes stuffed with $20 and $50 bills and loaded them into a trunk of a car. Andra and her State Department bodyguards drove across the border to the hotel which was less than a mile from the international line. Andra waited there and no one showed up. US government officials suggested she drive back to Hermosillo, which she did.

Meanwhile, the FBI, the CIA and other associated alphabet agencies tried to come up with as much information as they could about the kidnappers’ group, the People’s Liberation Army of Mexico. During the late 1960s and early 1970s there were many leftist groups in Mexico seeking to overthrow the government. Some of these groups had extensive networks throughout the country and had been established for many years. Other groups just seemed to spring up out of nowhere and were localized and had few members. Still others operated completely in the shadows. After some intense preliminary research, US intelligence came up with nothing; no rough members list, no manifesto and no previous public activities. This made the kidnapping of John Patterson even more suspect. To add to this, the forced media silence was somewhat of an anomaly. Most counter-government or terrorist groups at the time used media publicity to their advantage. Even the smallest organization comprised of just a handful of people used the press to get their message out and to make known to the world their cause. Not so with the People’s Liberation Army of Mexico.

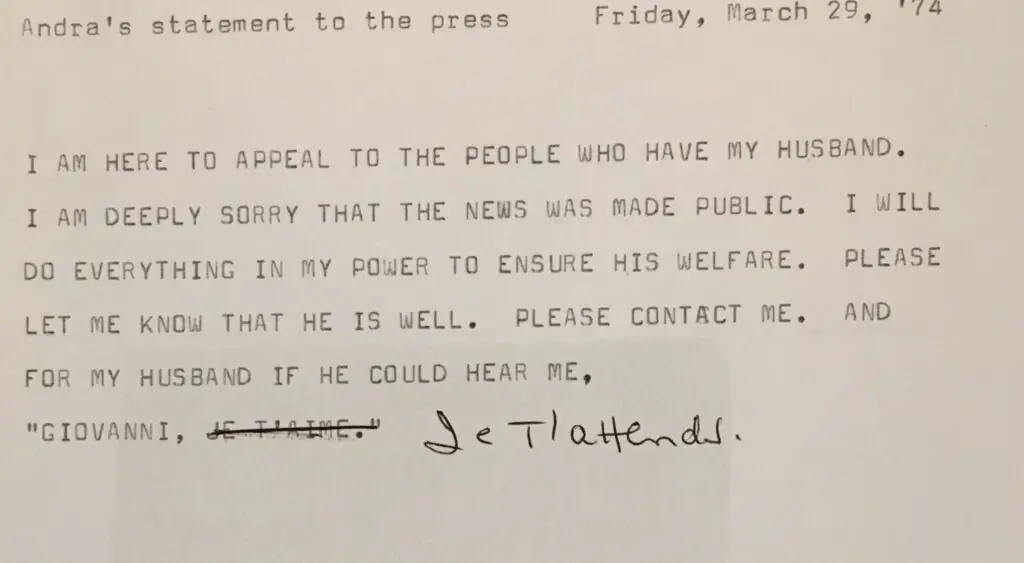

When Andra Patterson arrived back at Hermosillo, she was met with unsettling news. The vehicle John had been driving on the fateful morning he had been abducted had been found abandoned outside of town. Officials said that there was no sign of a struggle. Andra sat tight and awaited further instructions from the People’s Liberation Army of Mexico. The next day, March 27, 1974, the kidnapping case took a bad turn. In a press conference in Washington a reporter asked US Attorney General William Saxbe why he had canceled his upcoming trip to Mexico. Forgetting that he was not supposed to talk about the Patterson case as per the ransom note, Saxbe commented that the reason why he canceled his trip was because a US diplomat had been kidnapped. Crack reporters uncovered the facts of the case within hours and the next day a headline in The New York Times read, “U.S. Vice Consul Missing in Mexico.” Andra Patterson immediately became fearful of how the kidnappers would react, so with the help of US diplomats at the Hermosillo consulate, she wrote an apologetic statement to be released to the press which had amassed outside the residence of Elmer Yelton, the American consul. While this was going on, Mexican authorities began cracking down on suspected terrorists in the state of Sonora and arrested many members alleged to be part of the 23rd of September Communist League, an openly Marxist guerrilla group, which had been implicated in several terrorist attacks throughout the state. The Mexican government had recently killed one of the group’s leaders and it was widely suspected that John Patterson’s kidnapping was revenge for that killing. Authorities interrogated members of that communist league and got no answers as to the whereabouts of Patterson. Also, they had absolutely no information on the organization that supposedly kidnapped Patterson, the People’s Liberation Army of Mexico.

When Andra Patterson arrived back at Hermosillo, she was met with unsettling news. The vehicle John had been driving on the fateful morning he had been abducted had been found abandoned outside of town. Officials said that there was no sign of a struggle. Andra sat tight and awaited further instructions from the People’s Liberation Army of Mexico. The next day, March 27, 1974, the kidnapping case took a bad turn. In a press conference in Washington a reporter asked US Attorney General William Saxbe why he had canceled his upcoming trip to Mexico. Forgetting that he was not supposed to talk about the Patterson case as per the ransom note, Saxbe commented that the reason why he canceled his trip was because a US diplomat had been kidnapped. Crack reporters uncovered the facts of the case within hours and the next day a headline in The New York Times read, “U.S. Vice Consul Missing in Mexico.” Andra Patterson immediately became fearful of how the kidnappers would react, so with the help of US diplomats at the Hermosillo consulate, she wrote an apologetic statement to be released to the press which had amassed outside the residence of Elmer Yelton, the American consul. While this was going on, Mexican authorities began cracking down on suspected terrorists in the state of Sonora and arrested many members alleged to be part of the 23rd of September Communist League, an openly Marxist guerrilla group, which had been implicated in several terrorist attacks throughout the state. The Mexican government had recently killed one of the group’s leaders and it was widely suspected that John Patterson’s kidnapping was revenge for that killing. Authorities interrogated members of that communist league and got no answers as to the whereabouts of Patterson. Also, they had absolutely no information on the organization that supposedly kidnapped Patterson, the People’s Liberation Army of Mexico.

With investigations going nowhere, the FBI ramped up the scrutiny of the Pattersons themselves. Background checks of Andra showed that she had participated in several Vietnam War protests and was involved in other “progressive” causes. Given the lack of information on the kidnapper’s group and the attitude of a very conservative FBI at the time, the leading theory regarding John  Patterson’s disappearance was self-kidnapping in order to pocket the ransom money. That theory was leaked to the press in the US and Mexico. One newspaper’s headlines boldly proclaimed, “Police Assure that Disappearance of US Vice-Consul is a Self-Kidnapping.”

Patterson’s disappearance was self-kidnapping in order to pocket the ransom money. That theory was leaked to the press in the US and Mexico. One newspaper’s headlines boldly proclaimed, “Police Assure that Disappearance of US Vice-Consul is a Self-Kidnapping.”

On April 10 a call came into the US consulate in Hermosillo and the person on the other end of the line asked to speak to Andra Patterson. The caller’s voice was described as having “a slight Texas twang” and the man claimed that he was also kidnapped along with John Patterson. The caller said that the new drop-off point for the rest of the money and the release of the hostage would be the Rosarito Beach Hotel in Baja where they were both currently being held. The caller claimed that if the instructions weren’t followed, both he and John would be harmed. The call seemed fishy for two reasons. When asked for verification that John Patterson was still alive the caller could not provide proof. Also, when the FBI traced the call, they traced it to San Diego and not Rosarito Beach. Andra decided to go to the hotel anyway and this time alone. The same scenario played out: She waited at the hotel for days and no one showed up to make the exchange for her husband. Again, she returned to Hermosillo.

On May 6, 1974, the US consulate in Hermosillo received another letter from the alleged kidnappers. It was mailed from southern California on April 30 and instructed Andra to go back to Rosarito for a meeting on May 3rd, which had already passed. Andra then went to the press to appeal to the kidnappers directly. While this was happening, the FBI was zeroing in on a person of interest, a man named Bobby Joe Keesee who was once an Army paratrooper and had a checkered past, including multiple arrests and incarcerations. US officials found ample evidence in Keesee’s Huntington Beach apartment to link him to the crime, including the same green-colored stationery used to write the ransom letters. Later, the full story came out: Keesee’s father had retired to Hermosillo and Bobby Joe came up with a plan to kidnap the newest officer at the local US consulate, the 31-year-old John Patterson. Bobby Joe Keesee posed as a Texas cattle trader interested in doing business with Mexico. Keesee was the man John was meeting on that fateful day.

On July 8, 1974, a local man wandering through the deserts north of Hermosillo found what he thought was a large animal carcass. It was the body of John Patterson. He had been killed by a rifle butt to his face and to the back of his head. Authorities arrested Keesee and because there were no eyewitnesses and no physical evidence linking Keesee to the scene of the crime, Bobby Joe Keesee accepted a deal to plead guilty to one count of conspiracy to kidnap, specifically linked to the letters of extortion mailed from southern California. All charges related to the murder of American vice consul John Patterson were dropped. Keesee spent 11 years in prison for this crime. And what of the People’s Liberation Army of Mexico? It never even existed.

On July 8, 1974, a local man wandering through the deserts north of Hermosillo found what he thought was a large animal carcass. It was the body of John Patterson. He had been killed by a rifle butt to his face and to the back of his head. Authorities arrested Keesee and because there were no eyewitnesses and no physical evidence linking Keesee to the scene of the crime, Bobby Joe Keesee accepted a deal to plead guilty to one count of conspiracy to kidnap, specifically linked to the letters of extortion mailed from southern California. All charges related to the murder of American vice consul John Patterson were dropped. Keesee spent 11 years in prison for this crime. And what of the People’s Liberation Army of Mexico? It never even existed.

REFERENCES

Koerner, Brendan. “A Kidnapping Gone Very Wrong.” The Atlantic, May 2011.