Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

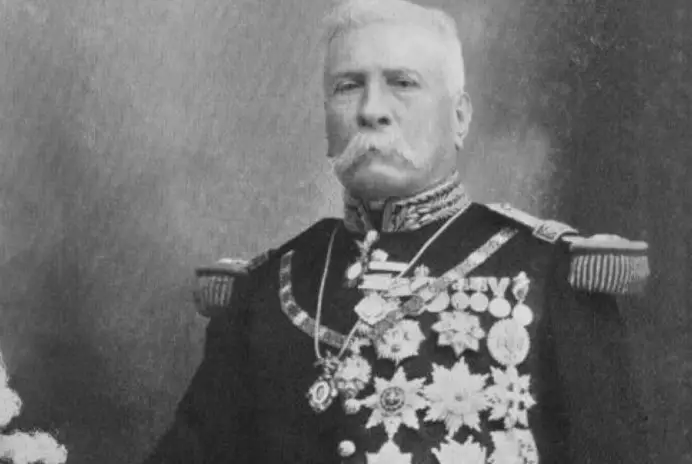

In the annals of Mexican history, few figures have cast as long a shadow as Porfirio Díaz. Serving as President of Mexico for 31 years during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Díaz’s political career is a complex tapestry woven with both accomplishments and controversy.

In the annals of Mexican history, few figures have cast as long a shadow as Porfirio Díaz. Serving as President of Mexico for 31 years during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Díaz’s political career is a complex tapestry woven with both accomplishments and controversy.

Although his exact date of birth is unknown, Porfirio Díaz was baptized on September 15, 1830, in Oaxaca, Mexico, and was most likely born a day or two before. Ironically, his baptismal date is the 20th anniversary of the eve of the Grito de Dolores, the call from Father Miguel Hidalgo that sparked Mexico’s war of independence from Spain. The future president of Mexico emerged from humble beginnings. The sixth of seven children, Porfirio’s father, José de la Cruz Díaz was a common laborer of mostly Spanish descent. Porfirio’s mother, María Patrona Mori Cortés was half Mixtec and the other half hailed from an old Spanish family from Asturias which had been in Mexico for hundreds of years. Porfirio Díaz’ father died when he was three, leaving María Patrona to raise the multiple Díaz children alone. Díaz’ godfather would sponsor him to attend the religious seminary at age 15 where he would study to become a priest. World events would change the boy’s path in life, however. Soon after entering the seminary, war broke out with the United States and Díaz was eager to participate. He joined a Oaxacan military battalion but never saw combat. The war was over before Díaz turned 18 but by then he had gotten a taste for all things military. In 1849 Díaz decided to quit his clerical studies at the seminary and pursue the study of law. While studying law, Díaz became close to one of his professors, the native Oaxacan Benito Juárez, another future president of Mexico discussed in Mexico Unexplained episode number 368: https://mexicounexplained.com/benito-juarez-the-indigenous-statesman-who-shaped-modern-mexico/ Díaz became a lawyer at the age of 23 and with thoughts of military service still in the back of his mind, he accepted a commission as captain in the National Guard in December of 1856. His military prowess became evident as he rose through the ranks, demonstrating strategic acumen and leadership skills that caught the attention of both allies and adversaries. In 1862, Díaz participated in the Battle of Puebla against the French interventionist forces which is today remembered on both sides of the border as the Cinco de Mayo holiday. Díaz’s military career showcased his commitment to the Liberal cause, aligning himself with the forces seeking to establish a more progressive and secular Mexico. His early experiences in the armed forces laid the groundwork for the political ambitions that would define his later years.

After a distinguished military career, Díaz shifted his focus to the complex world of Mexican politics. Mexico post-Emperor Maximilian was marked by instability and political fragmentation, providing fertile ground for ambitious leaders. Díaz emerged as a key player, aligning himself with Mexico’s Liberals while appeasing more conservative factions of Mexican society, like the Catholic Church. During Díaz’ rise to power he also became heavily involved in freemasonry, eventually becoming the highest-ranking mason in Mexico in his later years. Despite his attempts to play all sides, Mexico’s political landscape was fraught with power struggles, and Díaz found himself at odds with various factions.

In 1876, Díaz took up arms against the sitting president, Sebastián Lerdo de Tejada, igniting what historians call the Tuxtepec Revolution. Emerging victorious, Díaz assumed the presidency in 1877, marking the beginning of an era that would come to be known as the Porfiriato and sometimes also referred to as the “Pax Porfiriana,” or Porfirian Peace. Little did Mexico anticipate the profound impact of this extended period of rule.

In 1876, Díaz took up arms against the sitting president, Sebastián Lerdo de Tejada, igniting what historians call the Tuxtepec Revolution. Emerging victorious, Díaz assumed the presidency in 1877, marking the beginning of an era that would come to be known as the Porfiriato and sometimes also referred to as the “Pax Porfiriana,” or Porfirian Peace. Little did Mexico anticipate the profound impact of this extended period of rule.

Díaz’s presidency, spanning over three decades with intermittent periods of hiatus, brought about relative stability and economic growth. Implementing policies that attracted foreign investment, modernized infrastructure, and fostered economic development, Díaz sought to position Mexico as a modern and prosperous nation. Railways extended, telegraph lines crisscrossed the country, haciendas grew and increased production. Factories were built and Mexican-made products were being exported throughout the world. Foreign capital flowed into Mexico, mostly coming from the US, Great Britain, France and the newly consolidated German Empire. Unlike some of the previous Mexican presidents, Díaz enjoyed cordial and close relations with Mexico’s neighbor to the north, although he is credited with uttering the phrase, “Poor Mexico! So far from God, so close to the United States!” While most of Díaz’ predecessors sought to break the power of the Catholic Church as per the Reform Laws, under the Porfiriato the Church flourished and regained some of what it had lost during the Juarez years. Sometimes the church filled the gaps of what the government could not provide or didn’t want to provide, such as adequate public education. During the Díaz regime even the Jesuits had been welcomed back into Mexico after having been expelled in the 1760s. The religious freedom in Mexico at the time allowed for Protestant missionaries to come into the country for the first time, and  with them came an influx of new ideas. The Mexican peso during most of the Porfiriato was worth over three dollars US. All these changes seemingly transformed the nation. Mexico was becoming the envy of the world and a respected member of the community of nations.

with them came an influx of new ideas. The Mexican peso during most of the Porfiriato was worth over three dollars US. All these changes seemingly transformed the nation. Mexico was becoming the envy of the world and a respected member of the community of nations.

However, this era of progress was not without its costs. Díaz’s regime was characterized by an authoritarian rule marked by political repression and a blatant disregard for democratic principles. Elections were marred by fraud, opposition figures faced persecution, and dissent was met with force. Beneath the facade of stability lay a deep-seated undercurrent of social inequality, sowing the seeds of discontent that would eventually erupt.

While the Porfiriato ushered in economic growth and modernization, its benefits were unevenly distributed. The government’s mandate of land surveys to free up so-called unused or unclaimed land for sale and development was often at the cost of communal grazing, farming or hunting. Wealthy Mexicans and foreigners often bribed local officials to buy land that had been used by families and communities for hundreds of years. In fact, a friend of Porfirio Díaz obtained 12 million acres of land in Baja California by paying off local judges. Anyone who stood in the way of these shady land transfers was killed, imprisoned, or if they were indigenous, they were sold into servitude. United States companies owned almost 90% of Mexico’s mineral wealth, the national railroad and the entire Mexican oil industry. The concentration of wealth in the hands of a select few exacerbated social injustice, leaving most of the Mexican population, especially peasants and indigenous communities, marginalized and economically disenfranchised. Díaz was faced with recurring indigenous uprisings in the Yaqui and Maya homelands. Despite the outward appearance of prosperity, the discontent among the disenfranchised laid the groundwork for the revolutionary upheaval that would follow.

The working class, inspired by ideologies of social justice and equality, and fed up with decades of abuse and neglect, started to mobilize in the final years of the Porfiriato. Labor strikes, agrarian uprisings, and dissenting voices gained momentum, challenging the veneer of prosperity that the Porfirian regime presented to the world.

As general dissatisfaction simmered beneath the surface, opposition to Díaz’s rule gained momentum. A diverse coalition of revolutionary forces, including figures like Francisco Madero, Emiliano Zapata, and Pancho Villa, emerged to challenge the entrenched power structure. The call for land reform, labor rights, and a more inclusive political system resonated with the ordinary citizens who felt excluded from the prosperity. In 1910, Mexico held its presidential elections, and the 80-year-old Porfirio Díaz was declared the winner, almost unanimously. The opposition candidate, Francisco Madero, claimed massive voter fraud and called for a national revolt. Small rebellions then popped up throughout the country as an angry citizenry hoped to turn decades of frustration into political change. These multiple insurrections are seen by historians as being the initial phases of the Mexican Revolution, a protracted and bloody conflict aimed at dismantling existing power structures and ushering in a new era of social change. Facing mounting pressure, Díaz resigned in 1911 and went into exile in France. He died in Paris on July 2, 1915, at the age of 84.

As general dissatisfaction simmered beneath the surface, opposition to Díaz’s rule gained momentum. A diverse coalition of revolutionary forces, including figures like Francisco Madero, Emiliano Zapata, and Pancho Villa, emerged to challenge the entrenched power structure. The call for land reform, labor rights, and a more inclusive political system resonated with the ordinary citizens who felt excluded from the prosperity. In 1910, Mexico held its presidential elections, and the 80-year-old Porfirio Díaz was declared the winner, almost unanimously. The opposition candidate, Francisco Madero, claimed massive voter fraud and called for a national revolt. Small rebellions then popped up throughout the country as an angry citizenry hoped to turn decades of frustration into political change. These multiple insurrections are seen by historians as being the initial phases of the Mexican Revolution, a protracted and bloody conflict aimed at dismantling existing power structures and ushering in a new era of social change. Facing mounting pressure, Díaz resigned in 1911 and went into exile in France. He died in Paris on July 2, 1915, at the age of 84.

Porfirio Díaz’s legacy includes many accomplishments and much controversy. He is credited with modernizing Mexico, fostering economic growth, and establishing a degree of stability that set the stage for subsequent administrations to build upon. However, the human cost of these advancements, coupled with his autocratic rule, tarnished his legacy in the eyes of many. Díaz’s contributions to Mexican infrastructure, industry, and economic development cannot be overlooked. His vision for a modernized Mexico played a pivotal role in shaping the nation. However, the authoritarianism, political repression, and exacerbation of social inequality during his regime left an indelible mark on the collective memory.

The Porfiriato left an enduring impact on Mexican society, shaping its trajectory for decades to come. The scars of social injustice and political repression served as a stark reminder of the importance of inclusive governance and the need to address systemic inequalities. Díaz was also responsible for Mexico having term limits for its president. A president can only serve one 6-year term only, with no exceptions. Many Mexicans today are unsure what to think of this man. Porfirio Díaz’s influence on Mexico’s history is undeniable, and his legacy remains a subject of historical debate and reflection.

One thought on “Porfirio Díaz: The Good, the Bad, the Ugly”

Terrific overiew of the Porfiriata. I spent some time in Oaxaca fairly recently (3 years ago) and had an opportunty to visit with some young people I asked them the place in history of Emiliano Zapata and noted the rule of Porfiro Diaz. They all seemed to understand the greatness of Zapata. Not so much Porfiro Diaz. I at that time did not know Diaz was from Oaxaca.