Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

The date was January 5, 1688. The people of Puebla began a lengthy period of mourning for one of their most esteemed inhabitants. The 82-year-old woman they were mourning was named Catarina de San Juan and she was seen as a sort of living saint to many citizens of Puebla. Her story is a fascinating one and it begins in a slave market in southern India.

The date was January 5, 1688. The people of Puebla began a lengthy period of mourning for one of their most esteemed inhabitants. The 82-year-old woman they were mourning was named Catarina de San Juan and she was seen as a sort of living saint to many citizens of Puebla. Her story is a fascinating one and it begins in a slave market in southern India.

The woman who would be known as Catarina de San Juan was known as Mirra before she was captured by the Portuguese as a girl and sold into slavery at a market in the Indian city of Cochin. She was either 14 or 15 when this happened, and according to some accounts she ran away from her masters and sought refuge at a Jesuit mission somewhere in southern India where she learned Portuguese and became baptized, thus taking on the name Catarina de San Juan. After a year or so with the Jesuits, Catarina was captured again and was once again sold into slavery. This time, though, she did not stay in her native land of India. Instead, she was put on a boat bound for the slave market in Manila, in what was then the Spanish Philippines. This was in the year 1618. When she finally arrived at Manila, she was bought by someone who planned on reselling her to the Viceroy of New Spain, a man named Diego Carrillo de Medoza y Pimentel, the Marquess of Gélves. The viceroy was looking for “china” domestic servants instead of African ones, so this is the reason why he opted for sending for young women found at the slave markets in Manila.

It’s important to look at the cultural and historical contexts of the early 1600s before continuing with the story of Catarina’s illustrious life. Besides the well-known trans-Atlantic slave trade, there existed a lesser-known trans-Pacific slave trade that had a nexus point at Manila in the Spanish Philippines where the Manila Galleon would depart across the Pacific for Acapulco. In Manila, slaves  were bought and sold that came from as far away as Mozambique in eastern Africa, but most of them came from India, the Bengali coast and the Philippines themselves. The Portuguese controlled the slave trade in southern Asia and southeast Asia for the most part at the time, with one of their central slave markets located at Goa, a Portuguese colony on India’s west coast. All Asian-born slaves who passed through Manila in the 1600s were classified as “chino,” and this Manila Galleon transport of enslaved people is sometimes referred to as the “chino slave trade.” So, one did not need to be ethnically Chinese to be called “chino” in this context. The word was an umbrella term to refer to everyone Asian including Burmese, Filipino, Malay, Indonesian, and people from India. The “chino” slaves were highly prized in colonial Mexico in the 1600s as domestic servants because they were seen as more acculturated to Spanish ways than Africans. In most cases, African slaves came off ships directly from Africa, which were arriving to the New World with great frequency. The trans-Pacific slave trade was different. Many of the slaves who had been transported to Manila had spent months in the hands of the Portuguese before even arriving to the Spanish Philippines. While under the control of the Portuguese many of these “chino” slaves became Christian, learned Portuguese and became used to Iberian culture. Once transported to Manila, often these enslaved people waited months for transport on the Manila Galleon, thus becoming more acculturated to Spanish ways. As Spain was growing its colonial empire in the East, the demand for slave labor was great and there were many slaves who spent years in servitude in the Spanish Philippines before heading to Acapulco with the ultimate destination being somewhere in the interior of New Spain, usually Mexico City or Puebla. The “chino” slaves rarely worked in the fields but were usually domestic servants or workers in the textile mills or obrajes. These enslaved people enjoyed a greater degree of liberty as domestics and light industrial workers than the African slaves who toiled in the fields or in mines.

were bought and sold that came from as far away as Mozambique in eastern Africa, but most of them came from India, the Bengali coast and the Philippines themselves. The Portuguese controlled the slave trade in southern Asia and southeast Asia for the most part at the time, with one of their central slave markets located at Goa, a Portuguese colony on India’s west coast. All Asian-born slaves who passed through Manila in the 1600s were classified as “chino,” and this Manila Galleon transport of enslaved people is sometimes referred to as the “chino slave trade.” So, one did not need to be ethnically Chinese to be called “chino” in this context. The word was an umbrella term to refer to everyone Asian including Burmese, Filipino, Malay, Indonesian, and people from India. The “chino” slaves were highly prized in colonial Mexico in the 1600s as domestic servants because they were seen as more acculturated to Spanish ways than Africans. In most cases, African slaves came off ships directly from Africa, which were arriving to the New World with great frequency. The trans-Pacific slave trade was different. Many of the slaves who had been transported to Manila had spent months in the hands of the Portuguese before even arriving to the Spanish Philippines. While under the control of the Portuguese many of these “chino” slaves became Christian, learned Portuguese and became used to Iberian culture. Once transported to Manila, often these enslaved people waited months for transport on the Manila Galleon, thus becoming more acculturated to Spanish ways. As Spain was growing its colonial empire in the East, the demand for slave labor was great and there were many slaves who spent years in servitude in the Spanish Philippines before heading to Acapulco with the ultimate destination being somewhere in the interior of New Spain, usually Mexico City or Puebla. The “chino” slaves rarely worked in the fields but were usually domestic servants or workers in the textile mills or obrajes. These enslaved people enjoyed a greater degree of liberty as domestics and light industrial workers than the African slaves who toiled in the fields or in mines.

In 1619 Catarina de San Juan boarded a galleon bound for Acapulco. The journey took over 5 months. The trader responsible for Catarina disguised her as a boy for the voyage. This strange piece of her story was the result of an interesting historical footnote. Because of stories of abuse of female slaves on the long trip across the Pacific, the Spanish Crown decreed that there would be 3 male slaves for every female slave making the crossing, before abolishing trans-Pacific trafficking in female slaves altogether. Once in Acapulco, the merchant responsible for Catarina did not sell her to agents of the viceroy as planned. Heavy rains had flooded Mexico City and most of central New Spain and the viceroy’s people were not able to travel to Acapulco to pick her up. So, the slave trader  sold Catarina to a man from Puebla, a Portuguese captain named Miguel de Sosa, for ten times the price that the viceroy was going to pay for her, as she was a highly prized acculturated and Christianized “china” of around 18 years of age. Catarina then made the long trek from Acapulco to Puebla along harsh and hazardous roads. Settled into her new life in central Mexico, she was over 10,000 miles from her home in India and her south Asian ethnicity and dress made her somewhat of a curiosity on the streets of Puebla.

sold Catarina to a man from Puebla, a Portuguese captain named Miguel de Sosa, for ten times the price that the viceroy was going to pay for her, as she was a highly prized acculturated and Christianized “china” of around 18 years of age. Catarina then made the long trek from Acapulco to Puebla along harsh and hazardous roads. Settled into her new life in central Mexico, she was over 10,000 miles from her home in India and her south Asian ethnicity and dress made her somewhat of a curiosity on the streets of Puebla.

Catarina soon realized that in order to survive and thrive in her new environment, she needed to become a pious and obedient Christian, as this was highly prized by the colonial society of New Spain. Here is a written account describing her religiosity:

“She embraced Christianity and adopted ascetic practices depriving her body of food and comfort as part of her spiritual practice. Catarina in other words became a model of piety. She was selfless and dedicated to living a spiritual life and ignoring worldly concerns. From the Spanish perspective Catarina was an exemplary slave dutifully bearing the physical burdens of servitude to free her soul. She gave public thanks to the church for directing her soul to Christian salvation. Like Catarina other ‘chino’ slaves expressed a dedication to Christ that embodied the kind of religiosity favored by contemporary churchmen who imagined the creation of a new godly order among the natives of Mexico and the Philippines.”

Catarina’s master, the Portuguese captain de Sosa, would soon die and in his will he set her free. As a free woman in colonial Mexico, it was not respectable for her to be single, so a local priest married her to another “chino” who was still in servitude, a man named Domingo Suárez. Domingo may have been either Malay or Bengali, but his background is unclear. Catarina eventually bought his freedom, although the marriage didn’t end well. He was abusive to her and suddenly left her. Finding herself alone again, Catarina then went to a local convent where they took her in as a beata. “Beata” was a term used to describe a single woman, usually a widow, who led a form of religious life without belonging to any order, often wearing distinctive garb and engaged in charitable works. While in the convent she went into trances and claimed to have had visions of the Virgin Mary, the Baby Jesus and various saints. She became known around Puebla as a sort of mystic and was considered by some to be a strong faith healer. Sometimes people prayed to Catarina as if she were a saint. The pious came from miles away to listen to Catarina’s stories of her visions and religious ecstasies. She enjoyed the good favors of many notable people in colonial Puebla, from government officials and powerful clergy to members of the city’s high society. Catarina’s funeral, held at the church at the Jesuit College of Puebla, was attended by important people from as far away as Mexico City.

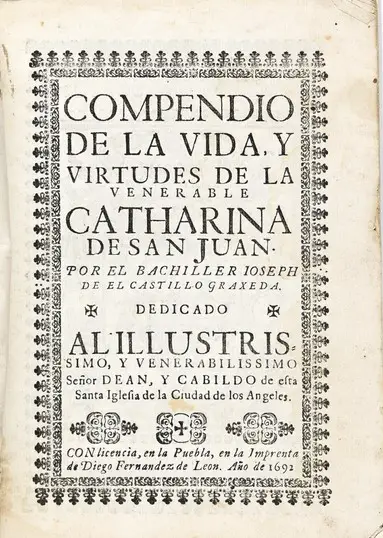

The popularity of Catarina de San Juan surged after her death. One of her confessors, the Jesuit Alonso Ramos, wrote a three-volume work on her life, which was the largest manuscript ever written in New Spain up until that time. Another clergyman, a parish priest named José del Castillo Grajeda, wrote embellished biographies on Catarina on the request of the viceroy. Some began venerating her and calling her Santa Catarina. The people of Puebla championed her cause to become a saint. Some historians believe they were inspired by the recent canonization of Saint Rose of Lima in 1671 which was the first proclamation of a saint by Rome in the New World. Poblanos tried to put Catarina on the same path to sainthood as Saint Rose and made formal appeals to church officials in Rome. Meanwhile, pictures of Catarina circulated along with images of the Virgin Mary and other saints, which caused some church fathers to be concerned. Eventually, the Holy Inquisition became involved.

The popularity of Catarina de San Juan surged after her death. One of her confessors, the Jesuit Alonso Ramos, wrote a three-volume work on her life, which was the largest manuscript ever written in New Spain up until that time. Another clergyman, a parish priest named José del Castillo Grajeda, wrote embellished biographies on Catarina on the request of the viceroy. Some began venerating her and calling her Santa Catarina. The people of Puebla championed her cause to become a saint. Some historians believe they were inspired by the recent canonization of Saint Rose of Lima in 1671 which was the first proclamation of a saint by Rome in the New World. Poblanos tried to put Catarina on the same path to sainthood as Saint Rose and made formal appeals to church officials in Rome. Meanwhile, pictures of Catarina circulated along with images of the Virgin Mary and other saints, which caused some church fathers to be concerned. Eventually, the Holy Inquisition became involved.

In 1691, just 3 years after Catarina’s death the Holy Inquisition decided to put a stop to the unbridled devotion to this former “china” slave turned religious superstar. The adoration shown to Catarina de San Juan is much like the devotions to folk saints like the Santa Muerte and Jesus Malverde in the Mexico of today; it was popular and outside the control of the Catholic Church. The Inquisition stepped in to right the ship and make sure that the public only venerated official saints formally canonized by Rome. So, in 1691, the Inquisition banned Catarina’s image along with the 3-volume work on her life written by the Jesuit Alonso Ramos. Anyone caught with these items in their possession would be visited by an inquisitor and punished. It is important to note that the Inquisition did not condemn Catarina de San Juan nor did they take a position on her possible candidacy for sainthood. Inquisitors were more concerned about the people who had taken the canonization process into their own hands and had started venerating Catarina as a saint.

Catarina de San Juan faded from most Mexicans’ memories until the 1800s when her story was incorporated into a legend of the “China Poblana,” a popular mode of dress that was essentially adopted as the national costume of Mexico during the presidency of Porfirio Díaz. Ultimately, there is no connection between Catarina and the popular China Poblana as historians have since debunked this.

Today, the house in which Catarina lived is a landmark in Puebla with a plaque on it proclaiming that Catarina was a “Moghul Princess” and was known as the original “China Poblana.” In some corners of Mexico, there is still some devotion to her, although there has been no recent interest to reopen her case to become a saint. Her story remains as a fascinating testament to a very obscure part of Mexican history. The epitaph on her tomb – translated to English – reads:

“I am a ship from China,

that disembarked a china.

Acapulco is too small a vessel

to carry this china.

My name is Catarina;

My direction is windward,

The Holy Spirit is the wind,

Saint Ignatius the captain,

His pilots will leave me,

In the land of salvation.”

REFERENCES