Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

An African slave named Estevanico was brought before the Viceroy of New Spain and kneeled in supplication. The viceroy, Antonio de Mendoza, was the king’s first official representative in this part of the New World. He had come to the newly conquered lands from the comfort of his station as a minor noble in Spain to seek his personal fortune and on this day in 1536 Mendoza felt as if he could become richer than the king of Spain himself. The kneeling slave before him recounted a tale of an odyssey lasting nearly nine years that went from the coast of Florida, through Texas and the present-day American Southwest and through most of northern Mexico. A key component of this tale was a rumor. The rumor told of seven cities in the north whose buildings were covered in gold and whose rulers were some of the wealthiest people on earth. As the second son of a wealthy Spanish count who had no right to inherit himself, Mendoza listened with wide eyes at the stories of what would henceforth be known as the Seven Cities of Gold. His course of action was clear: he would sponsor a massive expedition north to find these cities and to conquer them for the Spanish Crown, thus becoming wealthy in the process and making a name for himself in the New World.

An African slave named Estevanico was brought before the Viceroy of New Spain and kneeled in supplication. The viceroy, Antonio de Mendoza, was the king’s first official representative in this part of the New World. He had come to the newly conquered lands from the comfort of his station as a minor noble in Spain to seek his personal fortune and on this day in 1536 Mendoza felt as if he could become richer than the king of Spain himself. The kneeling slave before him recounted a tale of an odyssey lasting nearly nine years that went from the coast of Florida, through Texas and the present-day American Southwest and through most of northern Mexico. A key component of this tale was a rumor. The rumor told of seven cities in the north whose buildings were covered in gold and whose rulers were some of the wealthiest people on earth. As the second son of a wealthy Spanish count who had no right to inherit himself, Mendoza listened with wide eyes at the stories of what would henceforth be known as the Seven Cities of Gold. His course of action was clear: he would sponsor a massive expedition north to find these cities and to conquer them for the Spanish Crown, thus becoming wealthy in the process and making a name for himself in the New World.

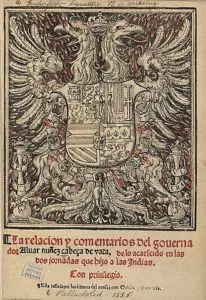

The story of the Seven Cities of Gold begins in 1522 when the aforementioned slave Estavanico was sold in a Morocco slave market to a minor Spanish nobleman named Andres Dorantes de Carranza. Dorantes took him to the New World in 1526 as part of an expedition led by Pánfilo de Narváez that set out to colonize the west coast of Florida, with aims of solidifying Spain’s claim on the peninsula. As soon as the Narváez expedition left the island Hispaniola in June of 1527, it was fraught with difficulty. The fleet encountered a very bad storm south of Cuba which caused them to lose 2 ships. The remaining tattered ships and demoralized the crew finally made it to the coast of Florida over 9 months later and many men deserted the expedition when they made landfall. After they landed near Tampa Bay they immediately pressed into the northern interior of Florida. What had originally started out as a 600-man expedition was reduced to 300 at the time of the encounter with the powerful Apalachee Indians in late 1528. At this point Narváez had a plan to build 4 large rafts, sail them down a river and skirt the Gulf Coast until he reached the Spanish outpost in the newly formed province of Pánuco located in the modern Mexican states of Veracruz and Tamaulipas. Once the rafts made it to the open ocean, two of the four were lost in a storm, with the leader of the group, Pánfilo de Narváez, on one of the lost rafts. The remaining two rafts made landfall somewhere near Galveston Island in September of 1528. By then there were only 86 men left and their de facto commander was a man named Alvar Nuñez Cabeza de Vaca who was the expedition’s marshal and treasurer. The disastrous Narváez expedition did not end on Galveston Island. The remaining survivors were taken into captivity by local natives and stayed on the Gulf Coast until 1532 when the last 4 of the expedition who were still alive made their escape. Over

The story of the Seven Cities of Gold begins in 1522 when the aforementioned slave Estavanico was sold in a Morocco slave market to a minor Spanish nobleman named Andres Dorantes de Carranza. Dorantes took him to the New World in 1526 as part of an expedition led by Pánfilo de Narváez that set out to colonize the west coast of Florida, with aims of solidifying Spain’s claim on the peninsula. As soon as the Narváez expedition left the island Hispaniola in June of 1527, it was fraught with difficulty. The fleet encountered a very bad storm south of Cuba which caused them to lose 2 ships. The remaining tattered ships and demoralized the crew finally made it to the coast of Florida over 9 months later and many men deserted the expedition when they made landfall. After they landed near Tampa Bay they immediately pressed into the northern interior of Florida. What had originally started out as a 600-man expedition was reduced to 300 at the time of the encounter with the powerful Apalachee Indians in late 1528. At this point Narváez had a plan to build 4 large rafts, sail them down a river and skirt the Gulf Coast until he reached the Spanish outpost in the newly formed province of Pánuco located in the modern Mexican states of Veracruz and Tamaulipas. Once the rafts made it to the open ocean, two of the four were lost in a storm, with the leader of the group, Pánfilo de Narváez, on one of the lost rafts. The remaining two rafts made landfall somewhere near Galveston Island in September of 1528. By then there were only 86 men left and their de facto commander was a man named Alvar Nuñez Cabeza de Vaca who was the expedition’s marshal and treasurer. The disastrous Narváez expedition did not end on Galveston Island. The remaining survivors were taken into captivity by local natives and stayed on the Gulf Coast until 1532 when the last 4 of the expedition who were still alive made their escape. Over  the next 4 years the 4 men – Cabeza de Vaca, Dorantes, the slave Estevanico and a man named Maldonado – traveled among the native tribes of the American Southwest and northern Mexico as traders and faith healers. The entire time the band of 4 was accompanied by various people of the different tribes they encountered. The group made it to the Pacific coast of Mexico in 1536 and soon met up with Spanish soldiers at an outpost near modern-day Culiacán, Sinaloa. From there it was an easy journey back to Mexico City and the court of the viceroy.

the next 4 years the 4 men – Cabeza de Vaca, Dorantes, the slave Estevanico and a man named Maldonado – traveled among the native tribes of the American Southwest and northern Mexico as traders and faith healers. The entire time the band of 4 was accompanied by various people of the different tribes they encountered. The group made it to the Pacific coast of Mexico in 1536 and soon met up with Spanish soldiers at an outpost near modern-day Culiacán, Sinaloa. From there it was an easy journey back to Mexico City and the court of the viceroy.

At court, the 4 men recounted the tales of their long journey and among those tales, as previously mentioned, was the rumor of the Seven Cities of Gold, also known as the Seven Cities of Cíbola. In their years of traveling in the northern reaches of New Spain they had never visited the seven cities themselves but only heard talk of them. This was enough to energize Viceroy Mendoza who immediately set up an expedition to the north. He wanted to make Dorantes a commander, but Dorantes wanted to return to Spain. As a result, Dorantes sold his slave Estevanico to the viceroy while he returned to Spain along with Cabeza de Vaca. The remaining man from the Narváez expedition, Maldonado, decided to stay in Mexico, but did not want part of the new expedition. The viceroy decided to send a Franciscan priest, Marcos de Niza, up north to investigate this legend with a small contingent of men, among them the African Estevanico as a scout. Estevanico was the only one on the new expedition with any experience in the northern territories.

The de Niza expedition got underway in 1539. Because Estevanico had experience in the northern lands, he traveled ahead of the main expedition as a scout, along with several indigenous guides. Estevanico had heard of the exact location of the Seven Cities and sent word back to de Niza that he was headed in the direction of the cities. Upon reaching the Zuni village of Hawikuh, the first of the supposed seven cities, Estevanico was rumored to be killed. Scholars have argued that Estevanico may have escaped with the help of the Zunis preferring to live among the Indians than return to Mexico City as a slave. One thing is certain: when rumors of Estevanico’s death reached de Niza who was in visual range of Hawikuh, de Niza turned the small expedition around and did not want to suffer the same fate as the African.

The de Niza expedition got underway in 1539. Because Estevanico had experience in the northern lands, he traveled ahead of the main expedition as a scout, along with several indigenous guides. Estevanico had heard of the exact location of the Seven Cities and sent word back to de Niza that he was headed in the direction of the cities. Upon reaching the Zuni village of Hawikuh, the first of the supposed seven cities, Estevanico was rumored to be killed. Scholars have argued that Estevanico may have escaped with the help of the Zunis preferring to live among the Indians than return to Mexico City as a slave. One thing is certain: when rumors of Estevanico’s death reached de Niza who was in visual range of Hawikuh, de Niza turned the small expedition around and did not want to suffer the same fate as the African.

In the summer of 1539 the de Niza expedition returned to Mexico City and the Franciscan related his story to Viceroy Mendoza. He claimed that he saw one of the seven cities from a distance and it glimmered in the sunlight, shiny from the gold and jewel-encrusted buildings. Later, scholars would claim that what de Niza saw was either reflections of minerals in the adobe bricks of the Zuni buildings, or corn drying on the rooftops of homes. De Niza told the viceroy that he only saw one city but was told by natives of the area that this one was the least wealthy of all of the seven cities and that there were richer kingdoms nearby, some with cities larger than Mexico City itself. Whether de Niza made this all up to please the viceroy, we may never know.

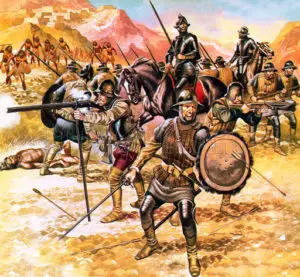

After the priest’s return, the time to put all the rumors to rest was at hand. In late 1539 Viceroy Mendoza asked the then-governor of the province of Nueva Galicia, Francisco Vázquez de Coronado, to lead a much larger expedition to find and subjugate the seven cities and to strip them of their gold and jewels. In February of 1540, Coronado soldiered north with 350 Spaniards, over 1,000 indigenous allies and the supporting wagons, firepower and livestock. On July 7, 1540 the first of Coronado’s men reached Hawikuh and were greeted by hundreds of Zunis firing arrows at them. Coronado ordered an attack on the village and all fighting stopped in an hour’s time. The starving and worn-down Spaniards were disappointed in not finding any gold or anything of great material value at Hawikuh or any of the other pueblo villages. Side expeditions went as far as the Colorado River, the Hopi mesas and the northern Rio Grande Valley. All side excursions found nothing of consequence and came up short. Distraught, Coronado headed east and spent the winter of 1540-1541 in the area of modern-day Albuquerque at a Tiwa pueblo village called Coohfor wondering what his next move will be.

After the priest’s return, the time to put all the rumors to rest was at hand. In late 1539 Viceroy Mendoza asked the then-governor of the province of Nueva Galicia, Francisco Vázquez de Coronado, to lead a much larger expedition to find and subjugate the seven cities and to strip them of their gold and jewels. In February of 1540, Coronado soldiered north with 350 Spaniards, over 1,000 indigenous allies and the supporting wagons, firepower and livestock. On July 7, 1540 the first of Coronado’s men reached Hawikuh and were greeted by hundreds of Zunis firing arrows at them. Coronado ordered an attack on the village and all fighting stopped in an hour’s time. The starving and worn-down Spaniards were disappointed in not finding any gold or anything of great material value at Hawikuh or any of the other pueblo villages. Side expeditions went as far as the Colorado River, the Hopi mesas and the northern Rio Grande Valley. All side excursions found nothing of consequence and came up short. Distraught, Coronado headed east and spent the winter of 1540-1541 in the area of modern-day Albuquerque at a Tiwa pueblo village called Coohfor wondering what his next move will be.

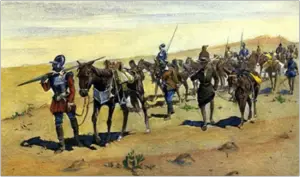

While wintering in the Rio Grande valley, Coronado heard another rumor from an indigenous man nicknamed “The Turk” about a fabulously wealthy city to the east, across the Great Plains called Quivira. Coronado, who was thinking of what would happen to him if he had returned to Mexico City empty-handed, decided to take the expedition east in hopes of finding this other city. In April of 1541 Coronado set off for Quivira. It is unknown whether the Indian named “The Turk” told Coronado of this fabled city to get the Spanish out of New Mexico and lost in the Great Plains, or whether the story was based on what The Turk thought to be true. In any case, Coronado felt he had nothing to lose and spent months crossing the harrowing Great Plains often getting disoriented due to the lack of landmarks to help guide him. In July of 1541 the Coronado expedition arrived at the agriculturally prosperous villages of the Wichita in central Kansas which was a welcome change from the endless plains. Here, too, there was no gold or anything else of material value for the Spaniards to take back to Mexico City with them. No  one even knows if these villages Coronado encountered were the fabled Quivira. Coronado, knew, though, that he could not press onward and needed to return to face the viceroy. In August of 1541, after spending 25 days in central Kansas, Coronado turned back and had the Indian informant, “The Turk,” strangled to death.

one even knows if these villages Coronado encountered were the fabled Quivira. Coronado, knew, though, that he could not press onward and needed to return to face the viceroy. In August of 1541, after spending 25 days in central Kansas, Coronado turned back and had the Indian informant, “The Turk,” strangled to death.

About 1,000 years before the Europeans arrived, what has later been called the Mississippian people had large urban centers in modern-day Missouri, Illinois, Arkansas and Kentucky, with one notable city, Cahokia, having over 40,000 inhabitants at its height. With its pyramids and ceremonial sites, perhaps Cahokia is the Quivira of legend, the wealthy city to the east, but we may never know.

When Coronado returned, the viceroy put the Seven Cities of Gold legend to rest. There would be no more expeditions in spite of persistent rumors. The last attempt to find the fabulous cities of gold happened as late as 1601, when the Spanish governor of New Mexico Juan de Oñate sent a small expedition to the area of Kansas and came up with nothing. It took nearly 75 years for the Spaniards to give up on the fantasy of the Seven Cities of Gold.

REFERENCES (Not a formal bibliography)

Cities of Gold by Douglas PrestonThe Seven Cities of Cibola by Stephen Clissold