Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

Get the official show t-shirt here: https://teespring.com/fear-the-nagual?tsmac=store&tsmic=mexico-unexplained&pid=266&cid=6174

Get the official show t-shirt here: https://teespring.com/fear-the-nagual?tsmac=store&tsmic=mexico-unexplained&pid=266&cid=6174

On a Sunday in October of 2013 the small church dedicated to Nuestra Señora de la Asunción – Our Lady of the Ascension – held a special mass for the worried townsfolk of the sleepy seaside town of Chicxulub Puerto located on the northern coast of the Yucatán. It was a very hot day, but the church was packed with parishioners searching for answers and comfort. Among the attendees was Alejandra, a gas station worker who had beheld a terrible sight just days before: a tall, clawed, hairy, growling creature crossed her path while she walked to work. Alejandra’s encounter was tied to the many horrible deaths of chickens throughout the town and the surrounding area. Hundreds of chickens were found dismembered and half eaten with feathers and parts strewn about large areas. Soon after Alejandra’s sighting, and a few other brief sightings about the town, the people in the town had collectively come to the conclusion that the strange creature lurking in their area and destroying their poultry stock was a demonic nagual.

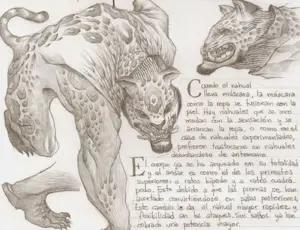

The modern Mexican folklore idea of a nagual, a cryptid on par with Bigfoot or the Chupacabra, has generated recent interest from cryptozoologists, or those who study unknown animals, and is much different from the nagual of old. The concept of the nagual has seem to shape-shift with the times and has been used to describe any number of hideous, evil creatures spotted throughout Mexico’s backcountry and mostly relegated to the darker hours of the day. The few common threads in the modern nagual story is that it is big and hairy, makes growling or howling noises and has the snout of a dog or sometimes the face of a cat. The nagual  is blamed for disappearances of animals or people and destruction of property. Today’s version of the nagual is not what we see in the historical record.

is blamed for disappearances of animals or people and destruction of property. Today’s version of the nagual is not what we see in the historical record.

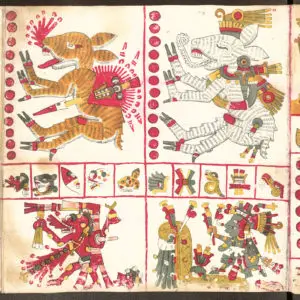

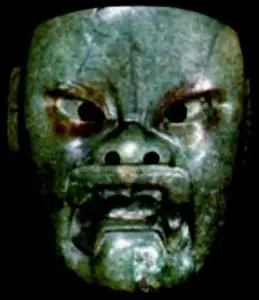

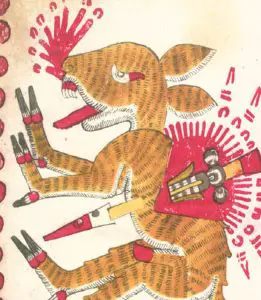

Some claim that the Codex Borgia, a pre-Hispanic pictographic bark book features naguales on page 22. The codex, which is essentially a calendar book created by Aztec scribes and used for purposes of divination, contains no written language, so there is no explanation of the figures claimed to be naguales on the page of the illustration. Most likely, the claim of modern-day analysists that these images are of “shape shifters” is not an accurate one. The word “nagual” is definitely pre-Columbian in origin. In the various languages in Mesoamerica, that word and similar words from the same stem or root, mean different things. For example, in Nahuatl, the language of the Aztecs, there is the word “naualli,” which means sorcerer, magician or enchanter and the word “nauallotl,” magic, enchantment or witchcraft. In the Quiché Maya language we have “naual,” a witch or sorcerer and the word “naualin,” which means “to tell fortunes,” or “to predict the future.” In the Tzental language spoken in the Mexican state of Chiapas there are similar words having to do with wisdom and memory. A “Ghnaoghel” is a wise man. That word is related to two other words, “naoghi,” “art, science” and “naoghibal,” “memory.” Yet another set of examples of similar words are found in the Zapotec language of Oaxaca. We have “nayanii,” which loosely translates to “the superior reason of man.” There are also two other similar words  “nayaa,” and “naguii,” which mean “superior or powerful man.” Although these words have existed in their respective languages for millennia, one researcher in the 1950s named Gustavo Correa has argued that the idea of the nagual and the mystical practices surrounding the nagual called “nagualism” were wholly imported from Europe and did not exist before the arrival of the Spanish. In his work titled El espíritu del mal en Guatemala, the author compared the idea of the nagual to the werewolves of medieval Europe and claims that because the nagual is so close to its European counterpart that it must have come to the Americas centuries ago with Spanish colonization as part of European folklore. Others counter Correa’s claim by citing evidence in stone of shape-shifting creatures, notably the were-jaguar figurines of the Olmecs dating back over 2,000 years and the more recent pre-Hispanic stone monuments of the Zapotec which show people turning into animals.

“nayaa,” and “naguii,” which mean “superior or powerful man.” Although these words have existed in their respective languages for millennia, one researcher in the 1950s named Gustavo Correa has argued that the idea of the nagual and the mystical practices surrounding the nagual called “nagualism” were wholly imported from Europe and did not exist before the arrival of the Spanish. In his work titled El espíritu del mal en Guatemala, the author compared the idea of the nagual to the werewolves of medieval Europe and claims that because the nagual is so close to its European counterpart that it must have come to the Americas centuries ago with Spanish colonization as part of European folklore. Others counter Correa’s claim by citing evidence in stone of shape-shifting creatures, notably the were-jaguar figurines of the Olmecs dating back over 2,000 years and the more recent pre-Hispanic stone monuments of the Zapotec which show people turning into animals.

The first mentioning of a nagual or nagualism by Europeans occurred in a 1530 writing by Antonio de Herrera called Historia de las Indias Occidentales. He was reporting, specifically, on the Maya. Translated from the Spanish, the author writes:

“The Devil was accustomed to deceive these natives by appearing to them in the form of a lion, tiger, coyote, lizard, snake, bird, or other animal. To these appearances they apply the name Naguales, which is as much as to say, guardians or companions; and when such an animal dies, so does the Indian to whom it was assigned. The way such an alliance was formed was thus: The Indian repaired to some very retired spot and there appealed to the streams, rocks and trees around him, and weeping, implored for himself the favors they had conferred on his ancestors. He then sacrificed a dog or a fowl, and drew blood from his tongue, or his ears, or other parts of his body, and turned to sleep. Either in his dreams or half awake, he would see some one of those animals or birds above mentioned, who would say to him, ‘On such a day go hunting and the first animal or bird you see will be my form, and I shall remain your companion and Nagual for all time.’ Thus their friendship became so close that when one died so did the other; and without such a Nagual the natives believe no one can become rich or powerful.”

“The Devil was accustomed to deceive these natives by appearing to them in the form of a lion, tiger, coyote, lizard, snake, bird, or other animal. To these appearances they apply the name Naguales, which is as much as to say, guardians or companions; and when such an animal dies, so does the Indian to whom it was assigned. The way such an alliance was formed was thus: The Indian repaired to some very retired spot and there appealed to the streams, rocks and trees around him, and weeping, implored for himself the favors they had conferred on his ancestors. He then sacrificed a dog or a fowl, and drew blood from his tongue, or his ears, or other parts of his body, and turned to sleep. Either in his dreams or half awake, he would see some one of those animals or birds above mentioned, who would say to him, ‘On such a day go hunting and the first animal or bird you see will be my form, and I shall remain your companion and Nagual for all time.’ Thus their friendship became so close that when one died so did the other; and without such a Nagual the natives believe no one can become rich or powerful.”

In another colonial account, this time from a priest named Father Bernardino de Sahagun, who was assigned to Aztec country, we see that the nagual is not an animal at all, but a person. In his work, Historia de Nueva España, the priest writes:

“The naualli, or magician, is he who frightens men and sucks the blood of children during the night. He is well skilled in the practice of this trade, he knows all the arts of sorcery (nauallotl) and employs them with cunning and ability; but for the benefit of men only, not for their injury. Those who have recourse to such arts for evil intents injure the bodies of their victims, cause them to lose their reason and smother them. These are wicked men and necromancers.”

“The naualli, or magician, is he who frightens men and sucks the blood of children during the night. He is well skilled in the practice of this trade, he knows all the arts of sorcery (nauallotl) and employs them with cunning and ability; but for the benefit of men only, not for their injury. Those who have recourse to such arts for evil intents injure the bodies of their victims, cause them to lose their reason and smother them. These are wicked men and necromancers.”

The church was very concerned in colonial times about the continuation of previous “pagan” religious practices and fortunate for the modern-day researcher there is a lot of material about Mesoamerican religious and folk-belief practices documented by the clergy. In an instructional book for confessors written in the year 1600 for priests with a predominately Indian congregation, Father Juan Bautista writes:

“There are magicians who call themselves teciuhtlazque, and also by the term nanahualtin, who conjure the clouds when there is danger of hail, so that the crops may not be injured. They can also make a stick look like a serpent, a mat like a centipede, a piece of stone like a scorpion, and similar deceptions. Others of these nanahualtin will transform themselves to all appearances, into a tiger, a dog or a weasel. Others again will take the form of an owl, a cock, or a weasel; and when one is preparing to seize them, they will appear now as a rooster, now as an owl, and again as a weasel. These call themselves nanahualtin.”

The type of animal used has to do with the day on which the conjurer was born, as each day in the Mesoamerican calendar is associated with a specific animal. It is unclear from Father Bautista’s writings if the person practicing nagualism is claiming to actually turn into these animals or if he is casting spells on witnesses to make others believe he is shape-shifting into something else.

The type of animal used has to do with the day on which the conjurer was born, as each day in the Mesoamerican calendar is associated with a specific animal. It is unclear from Father Bautista’s writings if the person practicing nagualism is claiming to actually turn into these animals or if he is casting spells on witnesses to make others believe he is shape-shifting into something else.

The practice of nagualism was not completely erased during the Spanish colonial period for curious reasons. When the Spanish Inquisition ramped up in the Spanish colonies of the Americas, the primary focus of the inquisitors were the Europeans or mixed bloods who were part of the European socirty of the New World. No great attention was paid to the Indians, especially those living their traditional ways away from urban centers, because, they were seen as ignorant and “not knowing any better.” Over the long course of the colonial period, the concept of the nagual thus became better documented by those who wished to learn more about the Mesoamerican natives.

Another primary source observation about the nagual from a Spanish historian Orozco y Berra writing in the latter colonial period states:

“The nahual is generally an old Indian with red eyes, who knows how to turn himself into a dog, woolly, black and ugly. The female witch can convert herself into a ball of fire; she has the power of flight, and at night will enter the windows and suck the blood of little children. These sorcerers will make little images of rags or of clay, then stick into them the thorn of the maguey and place them in some secret place; you can be sure that the person against whom the conjuration is practiced will feel pain in the part where the thorn is inserted. There still exist among them the medicine-men, who treat the sick by means of strange contortions, call upon the spirits, pronounce magical incantations, blow upon the part where the pain is, and draw forth from the patient thorns, worms, or pieces of stone. They know how to prepare drinks which will bring on sickness, and if the patients are cured by others the convalescents are particular to throw something of their own away, as a lock of hair, or a part of their clothing. Those who possess the evil eye can, by merely looking at children, deprive them of beauty and health, and even cause their death.”

For most of the recorded history of this phenomenon, the nagual has been considered a powerful person who, through the use of what is collectively known as “witchcraft”, changes into an animal or causes other people to think that he or she has changed. The term nagual has also been used by some Mesoamerican groups to denote a lifetime spirit guide represented by a real-world animal. The notion that the nagual is a cryptid, or unknown animal, is a more recent belief, as old memories of the real meanings of nagualism have died out or become murky down through the generations. Folk tales of legendary beasts and shape-shifters have changed over time and have developed into the mysterious creature we have today. Those claiming sightings of large, hairy, snarling, feline or doglike creatures in Mexico may have something altogether different on their hands not even related to anything conjured from old Indian magic.

For most of the recorded history of this phenomenon, the nagual has been considered a powerful person who, through the use of what is collectively known as “witchcraft”, changes into an animal or causes other people to think that he or she has changed. The term nagual has also been used by some Mesoamerican groups to denote a lifetime spirit guide represented by a real-world animal. The notion that the nagual is a cryptid, or unknown animal, is a more recent belief, as old memories of the real meanings of nagualism have died out or become murky down through the generations. Folk tales of legendary beasts and shape-shifters have changed over time and have developed into the mysterious creature we have today. Those claiming sightings of large, hairy, snarling, feline or doglike creatures in Mexico may have something altogether different on their hands not even related to anything conjured from old Indian magic.

REFERENCES

Brinton, Daniel Garrison. Nagualism. A Study in Native American Folk-lore and History. Independently Published, 2014 Get the book on Amazon here: https://amzn.to/35eK4Rg

Davis, Graem. Werewolves: A Hunter’s Guide. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing, 2015. Get the book on Amazon here: https://amzn.to/33hn6qT

Weaver, Muriel Porter. The Aztecs, the Maya and their Predecessors. New York: Academic Press, 1985. Get the book on Amazon here: https://amzn.to/30XJPGR

Historia de los Indios Occidentales by Antonio de Herrera (in Spanish)

Historia de la Nueva España by Bernardino de Sahagun

6 thoughts on “The Nagual”

could the mesoamerican nagual be related to the legendary race of naga which is referred to through asia india etc, the naga are reputed to be a serpent race of shape shifters with great powers for good or bad and supposedly guard temples throughout tailand and other asian regions

Could very well be. The other day I was reading parts of a book I was thinking of buying about how civilizations from ancient India may have had contact with Mexico 2,000 years ago.

I have seen a dog faced person walking through the woods during a festival a year ago. He had the body of a buff human male, but his face was smushed like a mix of bulldog, pig, and large cat.I left immediately after.

My mom, a nurse, has told me recently she moved a patient’s walking stick in his room. He got upset and said “Didn’t anyone teach you to not touch people’s belongings?” When he said that the end of the stick turned into a snake’s head with eye slits. Surprised she told the man, “Wow your stick looked like a snake for a second.” He replied “Hm, very good, Some people can’t see it.”

I’m in the states too, not mexico.

This is nothing more than the view of a western mind informed by other western minds. The opinions are taken from perspectives formed in a European mind set, which is devoid of knowledge of pre Columbian Mesoamerican cultures, world views and spiritual understandings. This regurgitation of European ethnocentric bias is laughable and without informative value.

Please give me a link to your work on the subject. I will happily display it here.

I am 100% with you on your comment. The folk who invaded this vast continent had to come up with tales to entertain the courts in Europe, hence all these distortions about the original peoples’ customs and culture and cognitive relationship to the universe at large.