Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

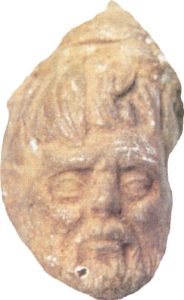

Although Romeo Hristov’s search was over, the controversy over what he had discovered, or had re-discovered, was only beginning to heat up again. In the spring of 1992 the archaeology student from the University of New Mexico finally located an artifact known by its catalog number, 20-1416, in the depths of the storage areas of the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City. The piece was a small terracotta head, a figurine eerily reminiscent of a traditional Santa Claus with its thick beard, chubby cheeks, a small nose and what appears to be a stocking cap on his head. Finely detailed, the features on the head look undeniably Caucasian with heavy facial hair unseen in ancient Mexico. Perhaps because of the piece’s look, the head had been misclassified by the museum and was included with items related to Mexico’s Spanish Colonial period. The young archaeology student had heard about this artifact, called the Tecáxic-Calixtlahuaca Head, after reading some papers published about it dating to the early 1960s. Hristov was overjoyed to have this precious piece in his hands to conduct more formal and in-depth studies.

Although Romeo Hristov’s search was over, the controversy over what he had discovered, or had re-discovered, was only beginning to heat up again. In the spring of 1992 the archaeology student from the University of New Mexico finally located an artifact known by its catalog number, 20-1416, in the depths of the storage areas of the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City. The piece was a small terracotta head, a figurine eerily reminiscent of a traditional Santa Claus with its thick beard, chubby cheeks, a small nose and what appears to be a stocking cap on his head. Finely detailed, the features on the head look undeniably Caucasian with heavy facial hair unseen in ancient Mexico. Perhaps because of the piece’s look, the head had been misclassified by the museum and was included with items related to Mexico’s Spanish Colonial period. The young archaeology student had heard about this artifact, called the Tecáxic-Calixtlahuaca Head, after reading some papers published about it dating to the early 1960s. Hristov was overjoyed to have this precious piece in his hands to conduct more formal and in-depth studies.

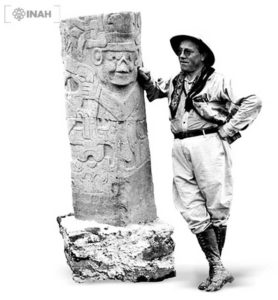

The mysterious head was found on a dig at a site called Calixtlahuaca in 1933 by a team headed by Mexican archaeologist José García Payón. Calixtlahuaca is located about 60 kilometers west of Mexico City near Toluca in an area that was conquered by the Aztecs in 1510, less than a decade before the arrival of the Spanish. The head was found in a burial under a pyramid and beneath two undisturbed cemented floors. Along with the head were offerings of items made of gold, copper and finished stone. The burial dates to the Azteco-Matalatzinca Phase, corresponding roughly from 1476 to 1510. It is important to note that Cortés first arrived at the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlán in 1519. The area of Calixtlahuaca was visited and conquered by the Spanish in the 1520s, most likely two decades or more after the head was placed in the burial. García Payón did not make public the find until some 27 years after its discovery. In 1960 he published his first paper about it and it was examined by various scholars in Mexico and Europe. The head caught the attention of Austrian anthropologist Robert Heine-Geldern in 1961 who declared that it was definitely a piece of art from the Greco-Roman Classical Age and suggested a date of manufacture of around 200 AD. This assertion was backed up by other European classicists over the years, including two professors who both served as presidents of the German Archaeological Institute in Rome, Erich Boehringer and Bernard Andreae. Professor Andreae was president of the institute in the late 1990s when he was visited by Hristov after the head was rediscovered. He had this to say about the head:

“It is Roman without any doubt… The stylistic examination tells us, more precisely, that it is a Roman work of the second century after Christ. It presents, in the cut of the hair and the shape of the beard, traits typical of the Severian emperors, exactly the ‘fashion’ of the period. On this there is no doubt.”

The Max Planck Institute in Heidelberg, Germany performed a thermoluminescence dating test on the artifact and came up with a time span of possible manufacture dating from between 870 BC and 1270 AD. While this test did not conclude that the head was of Roman origin, it ruled out the possibility that the head dated to Spanish colonial times, as it was originally classified in the National Museum of Anthropology. With artistic evaluations and scientific dating complete, the university student, Romeo Hristov, who rediscovered the head and brought it to the light of day, teamed up with Ra Expedition veteran and retired professor Santiago Genovés. They published their first paper on the mysterious head in 1999 and hit the academic lecture circuit soon after. They followed that up with a handful of other articles and publications. Many entrenched scholars had problems with the dating method used and Hristov’s very integrity. Hristov’s academic interests had to do with possible occasional or accidental contact between the Old World and ancient Mexico. To academia, which proposed NO cross-Atlantic contact in ancient times, even the mere suggestion of accidental contact seemed preposterous. Hristov and Genovés, as a result, became the targets of harsh criticism and character assassination by career intellectuals in the field of ancient Mesoamerica.

The Max Planck Institute in Heidelberg, Germany performed a thermoluminescence dating test on the artifact and came up with a time span of possible manufacture dating from between 870 BC and 1270 AD. While this test did not conclude that the head was of Roman origin, it ruled out the possibility that the head dated to Spanish colonial times, as it was originally classified in the National Museum of Anthropology. With artistic evaluations and scientific dating complete, the university student, Romeo Hristov, who rediscovered the head and brought it to the light of day, teamed up with Ra Expedition veteran and retired professor Santiago Genovés. They published their first paper on the mysterious head in 1999 and hit the academic lecture circuit soon after. They followed that up with a handful of other articles and publications. Many entrenched scholars had problems with the dating method used and Hristov’s very integrity. Hristov’s academic interests had to do with possible occasional or accidental contact between the Old World and ancient Mexico. To academia, which proposed NO cross-Atlantic contact in ancient times, even the mere suggestion of accidental contact seemed preposterous. Hristov and Genovés, as a result, became the targets of harsh criticism and character assassination by career intellectuals in the field of ancient Mesoamerica.

Dr. Michael E. Smith, a professor of anthropology at Arizona State University, offered a more even-handed criticism in a paper he released a few years after Hristov and Genovés published their first article on the “Roman Head.” Dr. Smith comes up with 6 possibilities to explain the existence of the head. In his words:

- This may be a hoax. This could be a Roman figurine, but it was planted at the site, or in the laboratory, by a student or colleague of the excavator.

The late Dr. John Paddock, a leading Mesoamerican scholar, used to tell classes at the Universidad de las Américas that the object was planted as a joke by Hugo Moedano, a student who worked at the site. Many archaeologists in Mexico have heard this story and they tend to believe it. I have checked with people who knew García Payón and some who knew Moedano, and I have been unable to confirm or reject this suggestion. Hristov and Genovés neglect to mention Paddock’s ideas in their article.

- This may be a Roman figurine, but it was introduced into the Calixtlahuaca artifact collections, after excavation, through error.

García Payón did not take extensive notes on his fieldwork, and it is entirely possible that extraneous objects may have been introduced into the collections after excavation. The collection of artifacts from Calixtlahuaca, now curated in the Museo de Antropología in Toluca, includes numerous donations of ceramic vessels from other sites, added to the collections after excavation. Perhaps the Roman figurine can be explained in a similar fashion.

- This may be a Roman figurine, but it was introduced to Calixtlahuaca in the early days of the Spanish colonial period.

It may have been brought from Europe to Mexico by a Spaniard, and it found its way into a Terminal Postclassic/Early Colonial offering at Calixtlahuaca. It is not possible to tell, from the contents or context, whether the offering dates to the period before the Spanish conquest of Mexico or from the early Spanish colonial period. My continuing analyses of these materials may shed light on this issue in the future.

It may have been brought from Europe to Mexico by a Spaniard, and it found its way into a Terminal Postclassic/Early Colonial offering at Calixtlahuaca. It is not possible to tell, from the contents or context, whether the offering dates to the period before the Spanish conquest of Mexico or from the early Spanish colonial period. My continuing analyses of these materials may shed light on this issue in the future.

- This is a post-Roman European Christian figurine, introduced to Calixtlahuaca in the early days of the Spanish colonial period.

This was the initial professional reaction upon García Payón’s publication of the object in 1960. I have yet to be convinced that the figurine really is Roman in origin – no one has shown illustrations of known Roman figurines next to this object. Could it be a post-Roman Christian figure? More research is needed. Arguments that this figurine is Roman in origin need to back that notion up with more than vague statements that “Professor so-and-so says that it looks Roman.”

- There is a slight chance that this may actually be a Roman figurine that somehow made its way from Europe to Mexico in ancient times.

It then may have been kept as a valuable good and ended up in a buried Postclassic offering at Calixtlahuaca. I seriously doubt this was the case, but it cannot be ruled out at this time.

- There are problems with the thermoluminescence dates reported by Hristov and Genovés. The physicists who ran the dates have objected to the way the dates are described by Hristov and Genovés.

Others wishing to discredit Hristov and Genovés, or even the head of the archaeological team who discovered the head back in 1933, will point to sloppy work done at the original Calixtlahuaca dig site. No photographs or drawings exist of the actual dig, and that means there is nothing showing the head in situ, or as it was found, lying in the ground among the other artifacts. García Payón did not catalog all the pieces at the site nor do photographs exist of the artifacts uncovered at the burial offering. There are no formal journals or expedition notes detailing the dig or describing in detail the offering where the head was discovered. There is also an absence of any written record of the find composed by any member of García Payón’s archaeological team at Calixtlahuaca. In short, critics allege that García Payón failed to meet the minimum standards of archaeological record keeping which only complicates the situation and sheds doubt on the claim that the artifact was a genuine Roman figurine found in a pre-Hispanic burial.

Within the past few years, the Tecáxic-Calixtlahuaca Head has undergone new scrutiny. Recent theorists have discarded the notion that the terracotta head is Roman at all or a colonial Spanish piece that somehow made it into a burial mound that predates the arrival of the conquistadores. Some have theorized that the artifact is really Viking in origin, even citing similarities to Norse artwork from a thousand years ago and comparing the hat on the figurine to similar headgear used in Scandinavia circa 1000 AD. Others have speculated that the piece may be Phoenician. In the year 2006 archaeologists discovered a Phoenician settlement on one of the Canary Islands off the coast of Africa. The trade winds from off the African coast could have carried Phoenician vessels across the Atlantic at least to the Caribbean Islands. In any case, the head could have made it to central Mexico in ancient times not necessarily from direct contact with a civilization from outside the New World, but through trade. The people who handled the head must have appreciated its rarity as it eventually ended up in a nobleman’s grave alongside gold, precious stones and other highly prized objects. Even with intense study from experts in various scientific fields, the mystery of this enigmatic head and how it ended up in ancient Mexico may never be solved.

Within the past few years, the Tecáxic-Calixtlahuaca Head has undergone new scrutiny. Recent theorists have discarded the notion that the terracotta head is Roman at all or a colonial Spanish piece that somehow made it into a burial mound that predates the arrival of the conquistadores. Some have theorized that the artifact is really Viking in origin, even citing similarities to Norse artwork from a thousand years ago and comparing the hat on the figurine to similar headgear used in Scandinavia circa 1000 AD. Others have speculated that the piece may be Phoenician. In the year 2006 archaeologists discovered a Phoenician settlement on one of the Canary Islands off the coast of Africa. The trade winds from off the African coast could have carried Phoenician vessels across the Atlantic at least to the Caribbean Islands. In any case, the head could have made it to central Mexico in ancient times not necessarily from direct contact with a civilization from outside the New World, but through trade. The people who handled the head must have appreciated its rarity as it eventually ended up in a nobleman’s grave alongside gold, precious stones and other highly prized objects. Even with intense study from experts in various scientific fields, the mystery of this enigmatic head and how it ended up in ancient Mexico may never be solved.

REFERENCES

García Payón, José. “Una cabecita de barro de extraña fisonomía.” INAH Bulletin, no. 6, 1961, pp. 1-2. (in Spanish)

Hristov, Romeo H. and Santiago Genovés. “Mesoamerica Evidence of Pre-Columbian Transoceanic Contacts.” Ancient Mesoamerica. 1999, 10 (2): 207-213.

Smith, Michael E. “The ‘Roman Figurine’ Supposedly Excavated at Calixtlahuaca.” Paper published online.

2 thoughts on “Ancient Roman Artifact Found in Mexico”

My grandmother found a First Century Roman coin in her vegetable garden in Rigby, Idaho in 1941. I have the coin and a letter in response to an inquiry she made about the history of the coin. It was surmised that it was a good luck token possibly carried by an explorer.

I wonder who the explorer was and more importantly, when! Thanks for sharing.