Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

The date was Monday, October 13, 2019. The 93-year-old Queen Elizabeth the Second delivered her annual speech to the House of Lords, marking the opening of Parliament. In a break with tradition, the Queen wore the George the Fourth State Diadem on her head instead of the more elaborate customary Imperial State Crown, which was by her side on a pillow. In a 2018 BBC documentary Her Majesty spoke about the sheer weight of the crown and how it made some ceremonial obligations difficult, especially in her advanced age. The Queen commented, “You can’t look down to read the speech; you have to take the speech up. Because if you did, your neck would break; it would fall off. So, there are some disadvantages to crowns, but otherwise they’re quite important things.” Indeed, the Imperial State Crown of the United Kingdom is quite heavy. In its gold frame and silver mounts, the crown has 2,868 diamonds, 17 sapphires, 11 emeralds and 269 pearls. One of those pearls has a curious nickname, “El Gran Limón,” or “The Great Lemon.” Even more curious than its obvious Spanish name is how this beautiful gem ended up in one of the most magnificent pieces of the Crown Jewels of the United Kingdom.

The date was Monday, October 13, 2019. The 93-year-old Queen Elizabeth the Second delivered her annual speech to the House of Lords, marking the opening of Parliament. In a break with tradition, the Queen wore the George the Fourth State Diadem on her head instead of the more elaborate customary Imperial State Crown, which was by her side on a pillow. In a 2018 BBC documentary Her Majesty spoke about the sheer weight of the crown and how it made some ceremonial obligations difficult, especially in her advanced age. The Queen commented, “You can’t look down to read the speech; you have to take the speech up. Because if you did, your neck would break; it would fall off. So, there are some disadvantages to crowns, but otherwise they’re quite important things.” Indeed, the Imperial State Crown of the United Kingdom is quite heavy. In its gold frame and silver mounts, the crown has 2,868 diamonds, 17 sapphires, 11 emeralds and 269 pearls. One of those pearls has a curious nickname, “El Gran Limón,” or “The Great Lemon.” Even more curious than its obvious Spanish name is how this beautiful gem ended up in one of the most magnificent pieces of the Crown Jewels of the United Kingdom.

The pearl was discovered in August of 1883 by a team of Mexican divers in the Sea of Cortez, also known as the Gulf of California, near San José Island off the coast of La Paz at the southern tip of the Baja Peninsula. One of the owners of the pearling company, a man named Antonio Ruffo, kept the gigantic pearl for himself, calling it “Carmenaida” after his two daughters, Carmen and Adelaida. Ruffo kept the pearl either on display in his company offices in La Paz or on his person whenever he traveled. On a trip to San Francisco, Antonio Ruffo showed the huge pearl to Sir Anthony Fein who was the UK ambassador to the United States and Mexico. Upon seeing the beautiful pearl, Sir Anthony wanted to buy it from Ruffo in order  to give it as a birthday gift to his sovereign, King Edward the Seventh. Instead of selling it to Fein, Antonio Ruffo decided to give his prized possession to the king himself. King Edward the Seventh was so impressed with the pearl he had one of the royal jewelers incorporate it into the Imperial State Crown. That amended crown was refashioned in 1937 for the coronation of the current queen’s father, King George the Sixth. The Queen was so curious about the origins of El Gran Limón that on her second visit to Mexico in February of 1983 she and her husband, Prince Philip, aboard their yacht Britannia, made a stop at La Paz. As an honored guest of the governor of the state of Baja California Sur, Alberto Andrés Alvarado, the Queen and her entourage went whale watching and toured the islands off the coast where the legendary beds of the black pearls once existed. A bronze plaque commemorating the visit along with the special pier built to receive the royal yacht still exist in La Paz.

to give it as a birthday gift to his sovereign, King Edward the Seventh. Instead of selling it to Fein, Antonio Ruffo decided to give his prized possession to the king himself. King Edward the Seventh was so impressed with the pearl he had one of the royal jewelers incorporate it into the Imperial State Crown. That amended crown was refashioned in 1937 for the coronation of the current queen’s father, King George the Sixth. The Queen was so curious about the origins of El Gran Limón that on her second visit to Mexico in February of 1983 she and her husband, Prince Philip, aboard their yacht Britannia, made a stop at La Paz. As an honored guest of the governor of the state of Baja California Sur, Alberto Andrés Alvarado, the Queen and her entourage went whale watching and toured the islands off the coast where the legendary beds of the black pearls once existed. A bronze plaque commemorating the visit along with the special pier built to receive the royal yacht still exist in La Paz.

Queen Elizabeth the Second is not the only European monarch to have in her possession one of the famous black pearls of the Sea of Cortez. 18th Century Russian Empress Catherine the Great had a necklace of 30 perfectly formed black pearls which were fished from these tropical Mexican waters. For many hundreds of years, the rare black pearl was called, “The queen of gems and the gem of queens,” as many female members of the European royal houses desired to possess these symbols of wealth and beauty. How uncommon are these black pearls? Here’s what an online resource called The Pearl Guide, says about these rare gems:

“Sea of Cortez Pearls originate from two species of mollusks that inhabit the Pacific coastline: the Panamic Black-Lipped Oyster (Pinctada mazatlanica) and the Rainbow-Lipped mollusk (Pteria sterna) both capable of producing pearls of incredible beauty. The Rainbow-Lipped Oyster produces pearls of highly unusual colorations and intense iridescence, thus producing a pearl that is clearly distinguishable from all others.”

“Sea of Cortez Pearls originate from two species of mollusks that inhabit the Pacific coastline: the Panamic Black-Lipped Oyster (Pinctada mazatlanica) and the Rainbow-Lipped mollusk (Pteria sterna) both capable of producing pearls of incredible beauty. The Rainbow-Lipped Oyster produces pearls of highly unusual colorations and intense iridescence, thus producing a pearl that is clearly distinguishable from all others.”

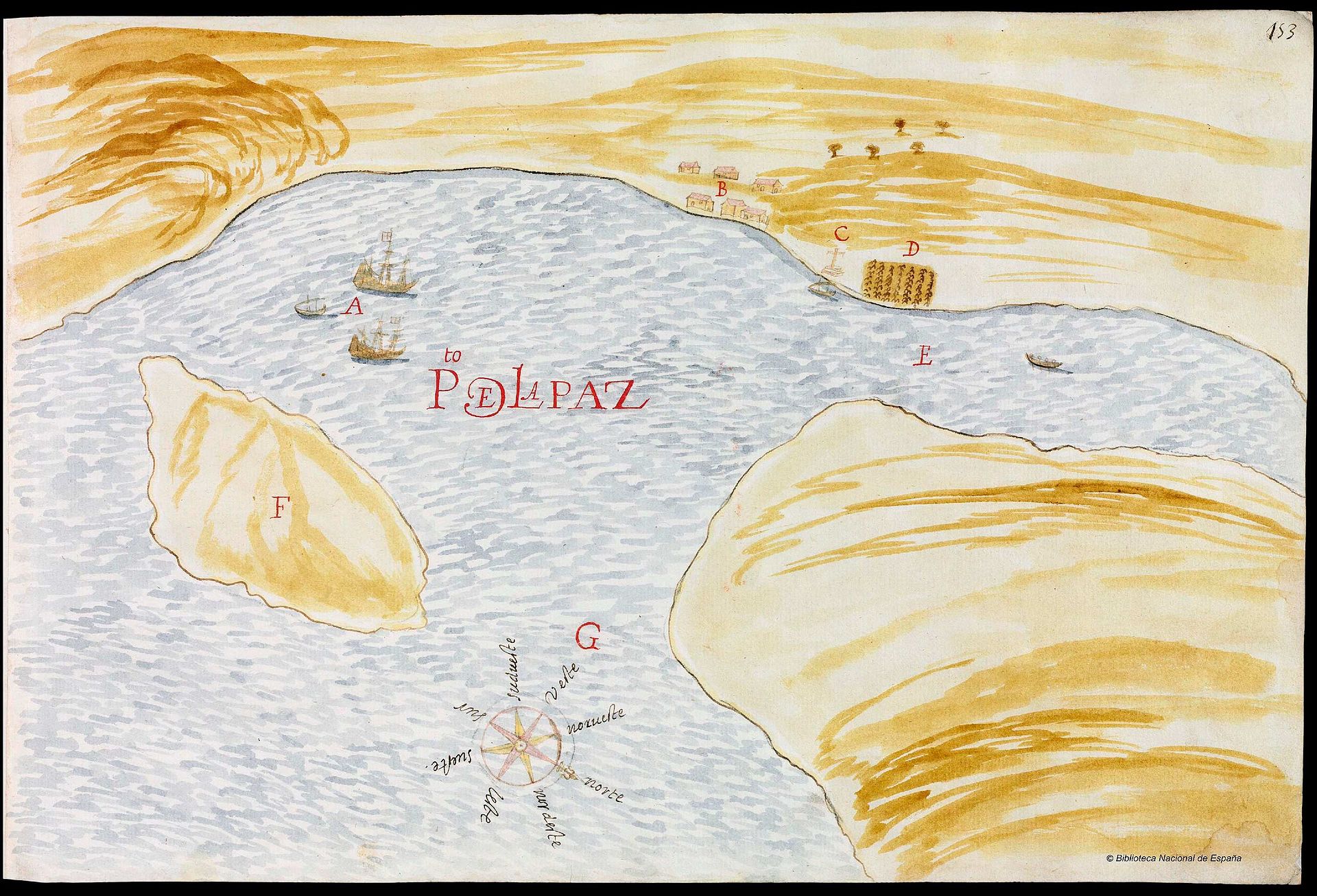

The black pearls of the Sea of Cortez first became known to the outside world in the 1530s, shortly after the Spanish conquest of the Aztecs. In 1532, Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés, sent two ships to explore the Pacific coast of Mexico to discover any unknown lands beyond. Under his agreement with the King of Spain, Cortés would have title to any newly discovered lands beyond New Spain. The purpose of this voyage was also to try to find the fabled Strait of Anián, a western end of a much-hoped-for Northwest Passage, an oceanic short cut to link Asia with Europe. The two ships Cortés sent out never returned, so in the following year, 1533, the conquistador outfitted two more ships, the Concepción and San Lázaro to sail from the small Pacific outpost of Manzanillo to look for the previous lost expedition. After less than a month at sea the ships became separated, and the crew of the Concepción mutinied, led by the ship’s navigator and second in command, Fortún Ximénez. Ximémez sailed the ship north and reached the Baja Peninsula which he thought was an island. Although Cortés would later call this new land Santa Cruz, the crew of the Concepción called this place California after the setting of a popular romance novel in Spain, Las sergas de Esplandián. In the novel, author Garci Rodriguez de Montalvo describes a mythical land of dark-skinned women ruled by a queen called Calafia. The name “California” stuck and was applied to this supposed island and later an entire region of New Spain to include the territory of the modern US state of California. While the crew of the Concepción did not find the land of beautiful women they were hoping for, they did notice that the inhabitants of this new land had curious adornments. While the locals wore little in the form of clothing, they did have necklaces with black pearls incorporated into them, something the Spanish sailors had never seen before. Knowing that these pearls would be a rare commodity, the Spanish began  to plunder the local indigenous villages looking for black pearls and other loot they could take back with them to Mexico City. After many confrontations with the natives and Ximénez killed, the remaining crew of the Concepción decided to take the ship and return to the Mexican mainland. They arrived on the Pacific shores of the modern Mexican state of Jalisco and the ship was requisitioned by representatives of the governor of the province of Nueva Galicia, the conquistador Nuño de Guzmán. The sailors made it back to Mexico City and handed over the black pearls and other items from the Baja natives to Cortés. Cortés saw the potential in the pearls, but upset with how the previous expeditions went, he decided to lead the third expedition himself. On May 3, 1535 Cortés landed at La Paz and established a colony there. Within weeks of its establishment, the colonists began fishing for the coveted black pearls. Cortés left La Paz to personally oversee the supply networks to sustain the colony and left a man named Francisco de Ulloa in charge of the fledgling colony. Relatives of the colonists, 800 miles away in Mexico City, put pressure on the viceroy of New Spain, Antonio de Mendoza, to abandon the La Paz colony. The viceroy decided to recall Ulloa and the colonists, and the pearl beds were abandoned, but not before the curious black pearls had already made it to European markets.

to plunder the local indigenous villages looking for black pearls and other loot they could take back with them to Mexico City. After many confrontations with the natives and Ximénez killed, the remaining crew of the Concepción decided to take the ship and return to the Mexican mainland. They arrived on the Pacific shores of the modern Mexican state of Jalisco and the ship was requisitioned by representatives of the governor of the province of Nueva Galicia, the conquistador Nuño de Guzmán. The sailors made it back to Mexico City and handed over the black pearls and other items from the Baja natives to Cortés. Cortés saw the potential in the pearls, but upset with how the previous expeditions went, he decided to lead the third expedition himself. On May 3, 1535 Cortés landed at La Paz and established a colony there. Within weeks of its establishment, the colonists began fishing for the coveted black pearls. Cortés left La Paz to personally oversee the supply networks to sustain the colony and left a man named Francisco de Ulloa in charge of the fledgling colony. Relatives of the colonists, 800 miles away in Mexico City, put pressure on the viceroy of New Spain, Antonio de Mendoza, to abandon the La Paz colony. The viceroy decided to recall Ulloa and the colonists, and the pearl beds were abandoned, but not before the curious black pearls had already made it to European markets.

Small expeditions into the Sea of Cortez to trade in the pearls occurred throughout the 16th and 17th centuries although no Europeans came to establish permanent settlements in Baja until the 1690s with the arrival of the Jesuits. The Jesuit Order set up a series of missions and oversaw the pearling industry. With little involvement from Mexico City in this desolate land, the Jesuits essentially ruled the Baja peninsula as their own private realm. Stories of the immense wealth of the Order reached Spain along with the black pearls themselves. The truth of it all was that the Jesuit fathers were eking out a hardscrabble existence in this harsh environment and much of the wealth that the black pearls generated occurred because they changed hands multiple times before reaching the high-end jewelers and royal houses of Europe. When the Jesuits were expelled from all parts of the Spanish Empire in 1768, those Spanish soldiers in charge of their expulsion from Baja were eager to get to the peninsula to get their hands on the wealth that the Jesuits were rumored to have. When they arrived to carry out their orders from the Spanish King to get rid of the Jesuits, the soldiers found an unbearable desert world so unlike the stories of abundance they had heard. This prompted further rumors that the Jesuits were hiding vast stores of gold and black pearls in a secret mission called Santa Isabel. For more information about this secret mission, please see Mexico Unexplained Episode Number 33. https://mexicounexplained.com//lost-mission-santa-isabel/

After the expulsion of the Jesuits black pearl fishing occurred intermittently throughout the colonial period. Diving for the pearls was somewhat difficult and posed certain hazards and risks. Pearl divers were paid little money for their efforts. Large scale operations began in the late 19th Century, like the one previously mentioned headed by Antonio Ruffo. By the early 20th Century the pearl beds were all but completely tapped out. The final nail in the coffin was the construction of the Hoover Dam which was completed in 1936. The dam prevented important nutrients from flowing south down the Colorado River and into the Sea of Cortez, thus dramatically affecting what little was left of the shellfish. During the presidency of Lázaro Cárdenas in 1939, a permanent ban was placed on all pearl fishing in the Sea of Cortez to save the few remaining pearl oyster populations. In 1993 a university research project began culturing pearls at Guaymas and three years later in 1996, commercial production started, thus putting the famous black pearls of the Sea of Cortez back on the jewelry markets.

Wherever there is great wealth or precious commodities, there are always myth, fables and assorted tall tales. Besides the “Lost Mission of Santa Isabel” and its stash of gold and black pearls, there is another fantastic story associated with these uniquely Mexican gems. According to a legend, in 1615, Juan de Iturbe, a Spanish explorer on a pearling expedition sailed up the coast of the Sea of Cortez to close to where the Colorado River empties into the sea. A high tidal bore took Iturbe’s caravel into Lake Cahuilla, a shallow saltwater basin that was once part of a gigantic lake that stretched well into the modern-day US state of California. In the early 1600s the lake was in its last stages of drying out. When the tide ebbed, the ship was stuck in the shallow lake and Iturbe was forced to beach his ship, leaving most of the precious cargo behind. The stranded Europeans marched south for many days to reach the closest Spanish settlement and never went back for the ship. Throughout the centuries, Iturbe’s ship has been discovered and lost several times over. In 1774 a member of the de Anza expeditions through what is now the American Southwest supposedly came across the ship in the middle of the desert an took away a fortune in black pearls. In 1907, on a ranch belonging to Niles Jacobsen located a few miles north of El Centro, California, a ranch hand named Elmer Carver noticed some strange-shaped fence posts on a remote section of the ranch. Mrs. Jacobsen told the ranch hand that the fence posts came from old wood from a ship they had discovered in the desert sands of their property. She also told Carver that she had found gems, including black pearls, inside the skeleton of the ship which she had sold to jewelers in Los Angeles. Others in and around California’s Imperial Valley have sighted the remnants of a ship in the middle of the desert as late as the 1970s. Whether these are just urban legends are unknown, but usually rumors do have some basis in fact. Whether from fantastic stories or through tangible jewelry, the black pearls of the Sea of Cortez continue to inspire wonder and awe.

Wherever there is great wealth or precious commodities, there are always myth, fables and assorted tall tales. Besides the “Lost Mission of Santa Isabel” and its stash of gold and black pearls, there is another fantastic story associated with these uniquely Mexican gems. According to a legend, in 1615, Juan de Iturbe, a Spanish explorer on a pearling expedition sailed up the coast of the Sea of Cortez to close to where the Colorado River empties into the sea. A high tidal bore took Iturbe’s caravel into Lake Cahuilla, a shallow saltwater basin that was once part of a gigantic lake that stretched well into the modern-day US state of California. In the early 1600s the lake was in its last stages of drying out. When the tide ebbed, the ship was stuck in the shallow lake and Iturbe was forced to beach his ship, leaving most of the precious cargo behind. The stranded Europeans marched south for many days to reach the closest Spanish settlement and never went back for the ship. Throughout the centuries, Iturbe’s ship has been discovered and lost several times over. In 1774 a member of the de Anza expeditions through what is now the American Southwest supposedly came across the ship in the middle of the desert an took away a fortune in black pearls. In 1907, on a ranch belonging to Niles Jacobsen located a few miles north of El Centro, California, a ranch hand named Elmer Carver noticed some strange-shaped fence posts on a remote section of the ranch. Mrs. Jacobsen told the ranch hand that the fence posts came from old wood from a ship they had discovered in the desert sands of their property. She also told Carver that she had found gems, including black pearls, inside the skeleton of the ship which she had sold to jewelers in Los Angeles. Others in and around California’s Imperial Valley have sighted the remnants of a ship in the middle of the desert as late as the 1970s. Whether these are just urban legends are unknown, but usually rumors do have some basis in fact. Whether from fantastic stories or through tangible jewelry, the black pearls of the Sea of Cortez continue to inspire wonder and awe.

REFERENCES

Herbert, Julian. Ahora imagino cosas. New York: Random House, 2019. We are an amazon affiliate. Buy the book on Amazon here: https://amzn.to/2ZGmrze

Navegantecalifornio web site (in Spanish)

The Pearl Guide (website)