Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

In the early morning hours of February 6, 1926 a graveyard caretaker was making a daily patrol of the grounds of the municipal cemetery of the town of Parral in the southern part of the Mexican state of Chihuahua. His name, almost lost to history in such a lesser-known place, was Juan Amparan. Amparan’s discovery would shock the whole nation of Mexico: The grave of the famous general, the hero of the Mexican Revolution, Pancho Villa, had been desecrated. Pancho Villa’s coffin had been disinterred during the night and his body mutilated. Amparan was reluctant to report to the municipal authorities later that morning that Villa’s body had been decapitated and the head was missing. None of the three gates to the cemetery had been forcibly opened, which led authorities to believe that the small wall surrounding the graveyard had been scaled by the perpetrator or perpetrators. Amparan reported that when he first came upon the desecrated grave he also found beside the broken pieces of the coffin lid a tequila bottle full of a mysterious liquid, and several cotton wads, one of them soaked in blood. The blood-soaked clump of cotton was quite mysterious as Villa’s body had been in the grave for 3 years and would thus not contain any blood. When the caretaker returned to the graveyard after making the report Amparan discovered that Villa’s grave was further ransacked by souvenir seekers who had not only taken away pieces of the broken coffin, but pieces of Villa’s remains. Later that day Amparan would attend a meeting with local officials at the Hotel Casa Fuentes in downtown Parral to discuss what would be done about such a violation.

In the early morning hours of February 6, 1926 a graveyard caretaker was making a daily patrol of the grounds of the municipal cemetery of the town of Parral in the southern part of the Mexican state of Chihuahua. His name, almost lost to history in such a lesser-known place, was Juan Amparan. Amparan’s discovery would shock the whole nation of Mexico: The grave of the famous general, the hero of the Mexican Revolution, Pancho Villa, had been desecrated. Pancho Villa’s coffin had been disinterred during the night and his body mutilated. Amparan was reluctant to report to the municipal authorities later that morning that Villa’s body had been decapitated and the head was missing. None of the three gates to the cemetery had been forcibly opened, which led authorities to believe that the small wall surrounding the graveyard had been scaled by the perpetrator or perpetrators. Amparan reported that when he first came upon the desecrated grave he also found beside the broken pieces of the coffin lid a tequila bottle full of a mysterious liquid, and several cotton wads, one of them soaked in blood. The blood-soaked clump of cotton was quite mysterious as Villa’s body had been in the grave for 3 years and would thus not contain any blood. When the caretaker returned to the graveyard after making the report Amparan discovered that Villa’s grave was further ransacked by souvenir seekers who had not only taken away pieces of the broken coffin, but pieces of Villa’s remains. Later that day Amparan would attend a meeting with local officials at the Hotel Casa Fuentes in downtown Parral to discuss what would be done about such a violation.

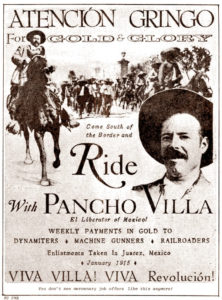

To give a little background of the man and the myth, Pancho Villa was born in the Mexican state of Durango in 1878 to laborers who worked on the largest hacienda in the state. At birth, Villa’s name was José Doroteo Arango Arámbula. He later changed his name to Francisco “Pancho” Villa after his father died because young Pancho claimed to be the illegitimate son of legendary northern bandit Agustín Villa, although there was no proof of this. Pancho Villa had a tumultuous youth and as a teenager he had already established himself as a bandit to be feared. By 1902 he had been forcibly inducted into the Mexican federal army, a common practice in dealing with minor criminals at the time. A few months after his induction, Villa killed an army officer, stole his horse and made his way north to Chihuahua. By 1910 Villa’s political sympathies lay with Francisco Madero, the national leader of the opposition to the long-lasting Porfirio Diaz dictatorship which had gripped Mexico for three and a half decades. The story of Pancho Villa’s military activities during the Mexican Revolution is a long and convoluted one, full of tall tales, bloodthirsty battles and heroic deeds. Among them was a famous raid on Columbus, New Mexico on March 9, 1916, which caused US President Woodrow Wilson to order the US Army into Mexico to capture Villa and his supporters, called villistas. After the US Army

To give a little background of the man and the myth, Pancho Villa was born in the Mexican state of Durango in 1878 to laborers who worked on the largest hacienda in the state. At birth, Villa’s name was José Doroteo Arango Arámbula. He later changed his name to Francisco “Pancho” Villa after his father died because young Pancho claimed to be the illegitimate son of legendary northern bandit Agustín Villa, although there was no proof of this. Pancho Villa had a tumultuous youth and as a teenager he had already established himself as a bandit to be feared. By 1902 he had been forcibly inducted into the Mexican federal army, a common practice in dealing with minor criminals at the time. A few months after his induction, Villa killed an army officer, stole his horse and made his way north to Chihuahua. By 1910 Villa’s political sympathies lay with Francisco Madero, the national leader of the opposition to the long-lasting Porfirio Diaz dictatorship which had gripped Mexico for three and a half decades. The story of Pancho Villa’s military activities during the Mexican Revolution is a long and convoluted one, full of tall tales, bloodthirsty battles and heroic deeds. Among them was a famous raid on Columbus, New Mexico on March 9, 1916, which caused US President Woodrow Wilson to order the US Army into Mexico to capture Villa and his supporters, called villistas. After the US Army  could not find him for almost a year, the mission was aborted. After the raid a rumor spread that the US government had a $50,000 to $100,000 bounty on the head of Pancho Villa. Although a resolution for this bounty was introduced in the US Congress at that time, it never passed, but that didn’t stop people from seeking the reward. With an imaginary price on his head, Villa continued his revolutionary exploits and in 1920 after several changes in power in Mexico City, Villa requested amnesty from the interim president Adolfo de la Huerta. Villa met with de la Huerta and in exchange for ceasing hostilities and abandoning his revolutionary army, Pancho Villa was granted a 25,000 acre hacienda outside of Parral, Chihuahua. Some 200 men who served in Villa’s armies worked and lived on the hacienda. The veterans were given 500,000 gold pesos as a pension by the Mexican government to live out the rest of their lives in peace in that quiet corner of Chihuahua. On July 20th, 1923, while running an errand in the town of Parral, Villa’s car was ambushed, and 40 shots later, the legendary Pancho Villa was dead. While motives are unclear, the biggest rumor was that Villa was considering a run for the presidency of Mexico in 1924 and certain factions wanted him stopped. Whatever the motives, it was certain that Villa had many enemies with many reasons to see him assassinated. He was laid to rest at the Parral cemetery in an ordinary plot.

could not find him for almost a year, the mission was aborted. After the raid a rumor spread that the US government had a $50,000 to $100,000 bounty on the head of Pancho Villa. Although a resolution for this bounty was introduced in the US Congress at that time, it never passed, but that didn’t stop people from seeking the reward. With an imaginary price on his head, Villa continued his revolutionary exploits and in 1920 after several changes in power in Mexico City, Villa requested amnesty from the interim president Adolfo de la Huerta. Villa met with de la Huerta and in exchange for ceasing hostilities and abandoning his revolutionary army, Pancho Villa was granted a 25,000 acre hacienda outside of Parral, Chihuahua. Some 200 men who served in Villa’s armies worked and lived on the hacienda. The veterans were given 500,000 gold pesos as a pension by the Mexican government to live out the rest of their lives in peace in that quiet corner of Chihuahua. On July 20th, 1923, while running an errand in the town of Parral, Villa’s car was ambushed, and 40 shots later, the legendary Pancho Villa was dead. While motives are unclear, the biggest rumor was that Villa was considering a run for the presidency of Mexico in 1924 and certain factions wanted him stopped. Whatever the motives, it was certain that Villa had many enemies with many reasons to see him assassinated. He was laid to rest at the Parral cemetery in an ordinary plot.

So, three years after his death and after any sort of bounty would be possible to claim, why would anyone want to steal the head of Pancho Villa? Let us return to the events of February of 1926. The first decapitation suspect was Salas Barraza who had recently been released from prison for his involvement in Villa’s assassination 3 years before. Barraza’s sister had been kidnapped by Villa’s army and left to die in the desert, and Barraza was suspected of the crime for reasons of revenge, but he had been closely monitored since his release from prison, so authorities were sure he was not the culprit. The authorities had to come up with a new suspect. One official in the town had heard a rumor that an institute in the United States had  offered a significant reward for the head of Pancho Villa to study the skull to help understand the revolutionary’s military genius. As bizarre as the theory may sound, the focus of the investigation shifted to any local American who might have had opportunity to make off with the skull. They had a new prime suspect, a tall, Iowa-born, Swedish-American adventurer named Emil Holmdahl who had participated in the US Army search for Pancho Villa after his raid on Columbus, New Mexico in 1916. Holmdahl was part of a group called The Adventurer’s Club, and with a few other Americans he had been in the Parral area hunting for a rumored treasure of gold bullion buried by Pancho Villa somewhere in the Sierra Madres. Holmdahl was arrested the day after the grave desecration. When his hotel room was searched, no decapitated head was found. The brother of the graveyard caretaker claimed to have seen Holmdahl and a companion at the cemetery earlier on the evening of the decapitation. Holmdahl admitted that he had been to Villa’s grave to pay his respects, but spent most of the night at the lively cantina called El Club Minero with many witnesses testifying to his presence there. After a period of questioning in the Parral jail, Holmdahl was released and left town immediately. Some people still did not absolve the American from his role in the beheading mystery. Holmdahl had been picked up for questioning the day after the event which gave him ample time to dispose of Villa’s head. Additionally, there had been a mysterious plane which landed in Parral the night of the incident. Some theorized that Holmdahl did the deed and the head was whisked away by the plane to that fabled American scientific institute that wanted to study it. As is customary in northern Mexico, Holmdahl’s involvement with the missing head legend was turned into a ballad. In English, here are the lyrics:

offered a significant reward for the head of Pancho Villa to study the skull to help understand the revolutionary’s military genius. As bizarre as the theory may sound, the focus of the investigation shifted to any local American who might have had opportunity to make off with the skull. They had a new prime suspect, a tall, Iowa-born, Swedish-American adventurer named Emil Holmdahl who had participated in the US Army search for Pancho Villa after his raid on Columbus, New Mexico in 1916. Holmdahl was part of a group called The Adventurer’s Club, and with a few other Americans he had been in the Parral area hunting for a rumored treasure of gold bullion buried by Pancho Villa somewhere in the Sierra Madres. Holmdahl was arrested the day after the grave desecration. When his hotel room was searched, no decapitated head was found. The brother of the graveyard caretaker claimed to have seen Holmdahl and a companion at the cemetery earlier on the evening of the decapitation. Holmdahl admitted that he had been to Villa’s grave to pay his respects, but spent most of the night at the lively cantina called El Club Minero with many witnesses testifying to his presence there. After a period of questioning in the Parral jail, Holmdahl was released and left town immediately. Some people still did not absolve the American from his role in the beheading mystery. Holmdahl had been picked up for questioning the day after the event which gave him ample time to dispose of Villa’s head. Additionally, there had been a mysterious plane which landed in Parral the night of the incident. Some theorized that Holmdahl did the deed and the head was whisked away by the plane to that fabled American scientific institute that wanted to study it. As is customary in northern Mexico, Holmdahl’s involvement with the missing head legend was turned into a ballad. In English, here are the lyrics:

“It struck the fancy,

Of a Saxon huckster

That he would make a lot of pesos

Exploiting a vein of gold ore.

He broke the concrete

With an iron crowbar

And removing the loose earth

He took the corpse from its crypt

He then cut off the head

Poor human remains

And leaving the grave open,

The American fled.”

Some believe there are clues to the motives of the theft in the ballad. “He would make lots of pesos / Exploiting a vein of ore” may be a reference to Pancho Villa’s hidden treasure that Emil Holmdahl and his friends in The Adventurer’s Club were looking for. One legend says that at one point – while he was still alive – Villa’s head was shaved and a map to his treasure was tattooed on his head. Perhaps whoever opened the tomb was operating on the assumption that possession of the head would be the key to finding untold riches.

The story involving Holmdahl did not end with his release from custody or with the famous ballad sung to him. In 1955, after the publication of his biography on Pancho Villa titled Coq of the Walk, author Haldeen Braddy received a letter from an aging Texas oil wildcatter named L. M. Shadbolt which recounted an encounter with Holmdahl in an El Paso hotel in 1927. According to the letter, Shadbolt and his business partner had been drinking heavily one night and met Holmdahl in the hotel bar. Holmdahl had taken up residence at this hotel soon after he had left Parral. After a few days of palling around with Shadbolt and his partner, Holmdahl invited the pair back to his room to show them a round object wrapped in newspaper. He peeled away layers of the paper to reveal the head of Pancho Villa, the look of frozen horror still on his face. The letter to the author concluded with Shadbolt explaining that Holmdahl told him he was being paid $5,000 for the skull by some buyer in Chicago. We are still left with a big question in this case, if Holmdahl did not use the skull as a treasure map, of what use would it have been to a buyer? Was the skull to undergo genuine scientific scrutiny or was the buyer a collector of the grotesque? Was the letter sent to the author almost 30 years after the incident a fake? If so, why would a letter like this be faked?

The story involving Holmdahl did not end with his release from custody or with the famous ballad sung to him. In 1955, after the publication of his biography on Pancho Villa titled Coq of the Walk, author Haldeen Braddy received a letter from an aging Texas oil wildcatter named L. M. Shadbolt which recounted an encounter with Holmdahl in an El Paso hotel in 1927. According to the letter, Shadbolt and his business partner had been drinking heavily one night and met Holmdahl in the hotel bar. Holmdahl had taken up residence at this hotel soon after he had left Parral. After a few days of palling around with Shadbolt and his partner, Holmdahl invited the pair back to his room to show them a round object wrapped in newspaper. He peeled away layers of the paper to reveal the head of Pancho Villa, the look of frozen horror still on his face. The letter to the author concluded with Shadbolt explaining that Holmdahl told him he was being paid $5,000 for the skull by some buyer in Chicago. We are still left with a big question in this case, if Holmdahl did not use the skull as a treasure map, of what use would it have been to a buyer? Was the skull to undergo genuine scientific scrutiny or was the buyer a collector of the grotesque? Was the letter sent to the author almost 30 years after the incident a fake? If so, why would a letter like this be faked?

There are two other legends surrounding the disappearance of the head of Pancho Villa. One is connected to the mysterious plane flight the night of the beheading. According to this story, the head was taken away by a Mexican general who opposed Villa during the Revolution, one of the many people who wanted to exact revenge on Villa, even after death. The head is now safely in the possession of the  general’s family somewhere in Mexico City. Another legend involves more powerful people north of the border. In a 1984 memoir written by Arizona rancher Ben F. Williams called Let the Tail go with the Hide, Williams alleges to have met Emil Holmdahl and not only did he admit to Williams that he had stolen Villa’s head, Holmdahl claimed to have sold it for $25,000 to Yale University’s Skull and Bones Society, the secret fraternal organization whose members include 3 generations of the Bush family. William’s account is the first tie-in with the Skull and Bones Society and people have theorized that somehow legends became crossed over time. For many years it has been rumored that Precott Bush, the father to the 41st president of the United States George Herbert Walker Bush and grandfather to President George W. Bush, was part of a group of bonesman who took the head of the Apache leader Geronimo to display at their secret Connecticut headquarters along with the heads of other notable people. Around the time of the 1988 presidential election with George HW Bush as the Republican nominee, tales of head stealing Skull and Bones members began making the rounds in the press, and the stories of Geronimo and Pancho Villa seemed to get confused. Besides the 1984 Williams memoir, no rumors had surfaced in the previous fifty-plus years that Yale’s secret society had any connection to the missing head of the famous Mexican general. In a Skull and Bones exposé written by Alexandra Robbins in 2002 titled Secrets of the Tomb: The Ivy League and the Hidden Paths to Power, the author claims that the secret society had possession of the famous skull. Under pressure, Robbins retracted the claim in an interview with the Yale Herald two years later.

general’s family somewhere in Mexico City. Another legend involves more powerful people north of the border. In a 1984 memoir written by Arizona rancher Ben F. Williams called Let the Tail go with the Hide, Williams alleges to have met Emil Holmdahl and not only did he admit to Williams that he had stolen Villa’s head, Holmdahl claimed to have sold it for $25,000 to Yale University’s Skull and Bones Society, the secret fraternal organization whose members include 3 generations of the Bush family. William’s account is the first tie-in with the Skull and Bones Society and people have theorized that somehow legends became crossed over time. For many years it has been rumored that Precott Bush, the father to the 41st president of the United States George Herbert Walker Bush and grandfather to President George W. Bush, was part of a group of bonesman who took the head of the Apache leader Geronimo to display at their secret Connecticut headquarters along with the heads of other notable people. Around the time of the 1988 presidential election with George HW Bush as the Republican nominee, tales of head stealing Skull and Bones members began making the rounds in the press, and the stories of Geronimo and Pancho Villa seemed to get confused. Besides the 1984 Williams memoir, no rumors had surfaced in the previous fifty-plus years that Yale’s secret society had any connection to the missing head of the famous Mexican general. In a Skull and Bones exposé written by Alexandra Robbins in 2002 titled Secrets of the Tomb: The Ivy League and the Hidden Paths to Power, the author claims that the secret society had possession of the famous skull. Under pressure, Robbins retracted the claim in an interview with the Yale Herald two years later.

There are many questions still remaining about what exactly happened that night in the Parral cemetery. A legend while alive, Pancho Villa continues to evoke wonder and a sense of mystery over a century after the Mexican Revolution. This bandit turned national folk hero will not rest peacefully, it is said, unless he is reunited with his stolen head. Until that time, what we have is one of the biggest mysteries in Mexican history.

REFERENCES (This is not a formal bibliography)

“The Head of Pancho Villa,” by Haldeen Braddy in Western Folklore, vol. 19, January 1960.

“Villa, Pancho (1878-1923),” by Claudio Buttice, in American Myths, Legends and Tall Tales: An Encyclopedia of American Folklore by Christopher R. Fee.

Coq of the Walk by Haldeen Braddy