Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

The fiesta in Bácum was one of the largest the town had ever seen. The year was 1876. After over 340 years of domination from outsiders, the dusty municipality located in the desert of Sonora had a reason to celebrate. The Yaqui leader known as Cajemé had just declared that the 8 Native American villages and their surrounding lands would henceforth be independent from Mexico, thus creating the first self-governing, sovereign, wholly indigenous political entity since the Spanish Conquest. While the town celebrated, the native elders knew that a peace with Mexico for their new country would be a long way away, and after three centuries of struggle many had their doubts of the new nation’s survivability. Cajemé had years of military experience, a deep knowledge of Mexican politics and culture, and overwhelmingly enthusiastic support from his people that seemed to contradict the feelings of the most cautious of the elders. The leader of the new country in what used to be the northwestern part of Mexico felt invincible on his day of declaration.

The fiesta in Bácum was one of the largest the town had ever seen. The year was 1876. After over 340 years of domination from outsiders, the dusty municipality located in the desert of Sonora had a reason to celebrate. The Yaqui leader known as Cajemé had just declared that the 8 Native American villages and their surrounding lands would henceforth be independent from Mexico, thus creating the first self-governing, sovereign, wholly indigenous political entity since the Spanish Conquest. While the town celebrated, the native elders knew that a peace with Mexico for their new country would be a long way away, and after three centuries of struggle many had their doubts of the new nation’s survivability. Cajemé had years of military experience, a deep knowledge of Mexican politics and culture, and overwhelmingly enthusiastic support from his people that seemed to contradict the feelings of the most cautious of the elders. The leader of the new country in what used to be the northwestern part of Mexico felt invincible on his day of declaration.

Cajemé was born to Yaqui parents in Villa de Pitic, now called Hermosillo, the modern-day capital of the Mexican state of Sonora, in 1835. His Christian name at baptism was José María Bonifacio Leiva Perez. His Yaqui name of Cajemé, used throughout most of his adult life, means “The one who does not stop to drink water.” Before we get into the life and times of this man and the independent republic formed in Sonora in the 1870s, we must first give a little background of the Yaqui people.

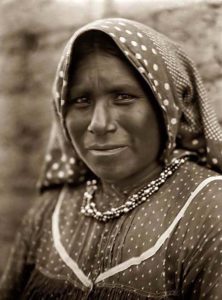

For thousands of years the Yaquis – also known as the Hiaki or Yoeme – and their ancestors occupied parts of the American Southwest and parts of the Mexican states of Sinaloa, Sonora and Durango. The Yaqui adapted to whatever geographical area they found themselves in. Those living on the Sea of Cortez lived a maritime existence and subsisted mostly on fish. Those who lived in the mountains and the northern deserts tended to be hunter-gatherers. The majority of the Yaqui people lived in villages and cultivated corn, beans and squash. The heartland of the Yaqui was along the Yaqui River, a lifeline flowing through one of the harshest deserts in Mexico. The first documented encounter between Yaquis and Europeans was in 1533 when a small expedition led by Diego de Guzmán entered Yaqui territory. In the early 1500s the Yaquis numbered about 30,000 living in almost 80 villages which were mostly located near the Yaqui River. When the first group of Yaquis met the Spanish face to face, a tribal elder literally made a line in the sand for the Spanish not to cross and told Guzmán to leave the area, refusing him food, water and shelter. A battle ensued and the Spanish retreated. Thirty years later an attempt to set up a Spanish colony in Yaqui territory failed and the settlers were driven back to central Mexico. In 1608 the Spanish and the Yaquis clashed once again, resulting in two disastrous defeats for the Spanish. A peace agreement was reached in 1610 and the Jesuits arrived seven years later to set up missions in Yaqui territory. The 150-year relationship the Yaquis had with the Jesuits was mutually beneficial and for the most part peaceful. Jesuits saved souls and set up small industry, the Indians got to keep most of their culture, their lands and social structure. The discovery of silver in Yaqui

For thousands of years the Yaquis – also known as the Hiaki or Yoeme – and their ancestors occupied parts of the American Southwest and parts of the Mexican states of Sinaloa, Sonora and Durango. The Yaqui adapted to whatever geographical area they found themselves in. Those living on the Sea of Cortez lived a maritime existence and subsisted mostly on fish. Those who lived in the mountains and the northern deserts tended to be hunter-gatherers. The majority of the Yaqui people lived in villages and cultivated corn, beans and squash. The heartland of the Yaqui was along the Yaqui River, a lifeline flowing through one of the harshest deserts in Mexico. The first documented encounter between Yaquis and Europeans was in 1533 when a small expedition led by Diego de Guzmán entered Yaqui territory. In the early 1500s the Yaquis numbered about 30,000 living in almost 80 villages which were mostly located near the Yaqui River. When the first group of Yaquis met the Spanish face to face, a tribal elder literally made a line in the sand for the Spanish not to cross and told Guzmán to leave the area, refusing him food, water and shelter. A battle ensued and the Spanish retreated. Thirty years later an attempt to set up a Spanish colony in Yaqui territory failed and the settlers were driven back to central Mexico. In 1608 the Spanish and the Yaquis clashed once again, resulting in two disastrous defeats for the Spanish. A peace agreement was reached in 1610 and the Jesuits arrived seven years later to set up missions in Yaqui territory. The 150-year relationship the Yaquis had with the Jesuits was mutually beneficial and for the most part peaceful. Jesuits saved souls and set up small industry, the Indians got to keep most of their culture, their lands and social structure. The discovery of silver in Yaqui  territory in 1684 caused some tensions between natives and Europeans, but did not cause the Yaquis to revolt. The next big uprising would be in 1740 when 5,000 Yaquis and 1,000 Spaniards were killed. The central government in Mexico City then decided to tighten control over these people. The Jesuits, long-time advocates for the Yaqui, had been losing power in the region by the mid-1700s and by the 1760s they were completely expelled from Mexico. With the departure of the Jesuits and the closing down of some of the missions, the Yaquis and the Spanish maintained an uneasy peace until the Mexican War of Independence began in 1810 and the Yaquis faced new challenges from a new group of people who now attempted to rule them from faraway Mexico City. During the Mexican fight for independence, while the government of Sonora and the Spanish elites of the area sided with the Spanish Crown, the Yaquis remained neutral and refused to participate in the conflict. To the new authorities in Mexico City, this indicated that the Yaquis considered themselves not to be subject to outside rule. The newly formed Mexican government, seeking to integrate all of former New Spain into the new political unit called Mexico, sent tax collectors to Yaqui lands proclaiming that the Yaquis were citizens of a new nation which needed money in its treasury. Given the Yaqui history of resistance to outside intervention, the tax collecting project did not go well. A revolt in 1825 beat back the new central Mexican government, but it returned intent on controlling every inch of Sonora. Thus began a series of minor revolts, skirmishes and guerilla attacks for the next 50 years until Cajemé proclaimed the new Yaqui republic in 1876.

territory in 1684 caused some tensions between natives and Europeans, but did not cause the Yaquis to revolt. The next big uprising would be in 1740 when 5,000 Yaquis and 1,000 Spaniards were killed. The central government in Mexico City then decided to tighten control over these people. The Jesuits, long-time advocates for the Yaqui, had been losing power in the region by the mid-1700s and by the 1760s they were completely expelled from Mexico. With the departure of the Jesuits and the closing down of some of the missions, the Yaquis and the Spanish maintained an uneasy peace until the Mexican War of Independence began in 1810 and the Yaquis faced new challenges from a new group of people who now attempted to rule them from faraway Mexico City. During the Mexican fight for independence, while the government of Sonora and the Spanish elites of the area sided with the Spanish Crown, the Yaquis remained neutral and refused to participate in the conflict. To the new authorities in Mexico City, this indicated that the Yaquis considered themselves not to be subject to outside rule. The newly formed Mexican government, seeking to integrate all of former New Spain into the new political unit called Mexico, sent tax collectors to Yaqui lands proclaiming that the Yaquis were citizens of a new nation which needed money in its treasury. Given the Yaqui history of resistance to outside intervention, the tax collecting project did not go well. A revolt in 1825 beat back the new central Mexican government, but it returned intent on controlling every inch of Sonora. Thus began a series of minor revolts, skirmishes and guerilla attacks for the next 50 years until Cajemé proclaimed the new Yaqui republic in 1876.

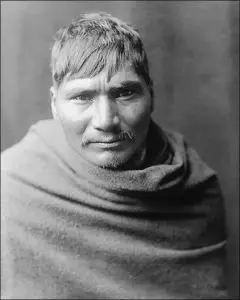

Cajemé was not born to any high station that prepared him to be a leader. His decisive role in the Yaqui independence movement came from a solid set of life experiences that made him ready when circumstances called on him. Born in 1835, he left his native land in 1849 to accompany his father Fernando to California which had been ceded to the United States in the Mexican War just a year before. His father was part of the large influx of people in the San Francisco/Sacramento area looking for gold. While in California helping his father as a gold prospector, Cajemé learned English and gained valuable experience in the larger world. Cajemé returned with Fernando two years later and because of his father’s success in the California gold fields, Cajemé was enrolled in an exclusive private school located in the town of Guaymas and excelled in his coursework, learning to read and write Spanish with ease. He impressed the schoolmaster, Cayetano Navarro, who was also the prefect of Guaymas. After leaving school Cajemé joined the local militia called the Urbanos which was captained by Navarro. When Cajemé was 18 he had his first taste of battle with the Urbanos as they had assisted Sonoran state authorities and the Mexican Army in quelling a series of rebellions in Sonora instigated by foreign mining interests. In the latter half of 1854, the 19-year-old Cajemé decided to leave Sonora and traveled to Tepic in the state of Nayarit where he became a blacksmith. Drawn to military service once again, he joined the Mexican Army, San Blas Battalion, but grew tired of it after 3 months. He deserted the army and fled to the mountains of Nayarit to work as a miner. Knowing that the army was searching for him for desertion, Cajemé went to Mazatlán and joined a battalion comprised mostly of indigenous fighters, specifically soldiers from the Pima, Mayo, Yaqui

Cajemé was not born to any high station that prepared him to be a leader. His decisive role in the Yaqui independence movement came from a solid set of life experiences that made him ready when circumstances called on him. Born in 1835, he left his native land in 1849 to accompany his father Fernando to California which had been ceded to the United States in the Mexican War just a year before. His father was part of the large influx of people in the San Francisco/Sacramento area looking for gold. While in California helping his father as a gold prospector, Cajemé learned English and gained valuable experience in the larger world. Cajemé returned with Fernando two years later and because of his father’s success in the California gold fields, Cajemé was enrolled in an exclusive private school located in the town of Guaymas and excelled in his coursework, learning to read and write Spanish with ease. He impressed the schoolmaster, Cayetano Navarro, who was also the prefect of Guaymas. After leaving school Cajemé joined the local militia called the Urbanos which was captained by Navarro. When Cajemé was 18 he had his first taste of battle with the Urbanos as they had assisted Sonoran state authorities and the Mexican Army in quelling a series of rebellions in Sonora instigated by foreign mining interests. In the latter half of 1854, the 19-year-old Cajemé decided to leave Sonora and traveled to Tepic in the state of Nayarit where he became a blacksmith. Drawn to military service once again, he joined the Mexican Army, San Blas Battalion, but grew tired of it after 3 months. He deserted the army and fled to the mountains of Nayarit to work as a miner. Knowing that the army was searching for him for desertion, Cajemé went to Mazatlán and joined a battalion comprised mostly of indigenous fighters, specifically soldiers from the Pima, Mayo, Yaqui  and Opata tribes. As a trooper in the army, Cajemé caught the attention of General Ramón Corona due to his ability to speak 3 languages and his previous military experience. In the nearly dozen years as General Corona’s aide-de-camp, Cajemé participated in the War of Reform and fought against the French during the reign of the Habsburg Emperor of Mexico, Maximilian. As an aside, most Yaquis back in Sonora at the time liked having the French in power in Mexico City because Maximilian represented weak central government control in a faraway capital which would leave them alone for the most part. Cajemé rounded out his military career by serving under the command of Ignacio Pesqueira who made Cajemé a captain in the cavalry. When Ignacio Pesqueira became governor of Sonora, he had big plans for Cajemé. He named him to the office of Alcalde Mayor of the Yaqui people, an appointment Pesqueira had hoped would end the Yaqui problem forever. Cajemé had proved his loyalty to Mexico and Pesqueira thought him perfect for the job. This was 1872.

and Opata tribes. As a trooper in the army, Cajemé caught the attention of General Ramón Corona due to his ability to speak 3 languages and his previous military experience. In the nearly dozen years as General Corona’s aide-de-camp, Cajemé participated in the War of Reform and fought against the French during the reign of the Habsburg Emperor of Mexico, Maximilian. As an aside, most Yaquis back in Sonora at the time liked having the French in power in Mexico City because Maximilian represented weak central government control in a faraway capital which would leave them alone for the most part. Cajemé rounded out his military career by serving under the command of Ignacio Pesqueira who made Cajemé a captain in the cavalry. When Ignacio Pesqueira became governor of Sonora, he had big plans for Cajemé. He named him to the office of Alcalde Mayor of the Yaqui people, an appointment Pesqueira had hoped would end the Yaqui problem forever. Cajemé had proved his loyalty to Mexico and Pesqueira thought him perfect for the job. This was 1872.

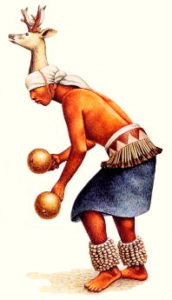

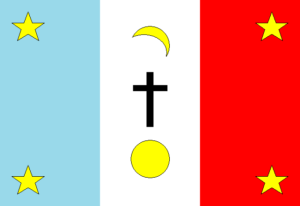

Instead of pacifying the Yaquis once and for all, Cajemé announced that he did not recognize the Mexican government, united the 8 Yaqui towns and surrounding lands, and declared and independent Yaqui republic. The government of the new nation would be based on the traditional Yaqui social structure with each town having 5 governing groups called yau’uras. There was a yau’ura for civil authority, one for military authority, one for fiesta authority, another for religious authority and one called the kohtumbre yau’ura which preserved the sacred customs surrounding Holy Week, including the Deer Dance. The governing bodies would be elected from groups of elders in each town and each yau’ura would vote democratically on issues facing it. As a social  reformer, Cajemé reinstituted the notion of communal ownership of Yaqui lands within the Yaqui territory. He initiated taxation and foreign trade controls. Cajemé told the Mexican authorities that his new nation would not recognize Mexico if they did not give the Yaquis the autonomy they had craved for centuries. It all seemed good and well, but while the Yaquis were fortifying themselves and building a new nation with enthusiasm and hope for the future, the central government in Mexico City had other plans for the so-called Yaqui Republic.

reformer, Cajemé reinstituted the notion of communal ownership of Yaqui lands within the Yaqui territory. He initiated taxation and foreign trade controls. Cajemé told the Mexican authorities that his new nation would not recognize Mexico if they did not give the Yaquis the autonomy they had craved for centuries. It all seemed good and well, but while the Yaquis were fortifying themselves and building a new nation with enthusiasm and hope for the future, the central government in Mexico City had other plans for the so-called Yaqui Republic.

The new war between the Yaqui and Mexico featured a succession of battles and brutalities on both sides. By 1885, there was dissent coming from the ranks of the Yaqui military. One of Cajemé’s officers, Loreto Molina, tried to take over the government of the new republic, and with the help of Mexican authorities, had a plan to assassinate Cajemé. Cajemé heard of the plot and fled but by then he was a marked man. The Mexican government sent a well-equipped force of 1,200 men to end the Yaqui independence movement once and for all. Of note to military historians, this force carried two primitive machine guns which would be the first to be used in major combat. When the force arrived at the Yaqui River, the first Mexican company  met with defeat and retreated. By the middle of 1886, however, it seemed as if the Mexican forces would win, as they had captured Cajemé’s fort at El Añil and destroyed much of the Yaqui military’s other fortifications. On a tip from a woman who was loyal to Loreto Molina and who opposed the endless wars with Mexico, Cajemé was captured in the small Indian village of San José de Guaymas, just north of the town of Guaymas, on the 13th of April, 1887. His captor was General Angel Martínez who would later rise to the position of Vice President under the reign of dictator Porfirio Díaz. Martínez put Cajemé on a gunboat that sailed up the Yaqui River and paraded him around the Yaqui towns to make sure everyone knew he was captured. On April 23, 1887, at eleven in the morning, Cajemé was shot by firing squad, thus ending his life and the dreams of the new indigenous republic that briefly existed in Sonora.

met with defeat and retreated. By the middle of 1886, however, it seemed as if the Mexican forces would win, as they had captured Cajemé’s fort at El Añil and destroyed much of the Yaqui military’s other fortifications. On a tip from a woman who was loyal to Loreto Molina and who opposed the endless wars with Mexico, Cajemé was captured in the small Indian village of San José de Guaymas, just north of the town of Guaymas, on the 13th of April, 1887. His captor was General Angel Martínez who would later rise to the position of Vice President under the reign of dictator Porfirio Díaz. Martínez put Cajemé on a gunboat that sailed up the Yaqui River and paraded him around the Yaqui towns to make sure everyone knew he was captured. On April 23, 1887, at eleven in the morning, Cajemé was shot by firing squad, thus ending his life and the dreams of the new indigenous republic that briefly existed in Sonora.

As a postscript, the Yaquis did not fare well immediately after Cajemé’s execution. Tired of the endless wars and skirmishes, the Mexican government decided to end the Yaqui “problem” once and for all. Although many Yaquis went into hiding and escaped to the mountains or fled to neighboring states, many were captured by the Mexican government and sold into slavery. The slaves were taken  to the Yucatán to work on plantations and many Yaquis did not survive the alien tropical climate or the harsh living and working conditions. The more troublesome members of the tribe were either executed or deported to faraway places such as the islands of the Caribbean or the nation of Bolivia in South America. In spite of all of this, the remaining Yaquis in Sonora continued to resist the Mexican government in one way or another. After the “last stand” of the Yaquis at what has been called the Battle of Cerro del Gallo in 1927, Mexico established armed garrisons in each village with a majority Yaqui population. This was a solution that seemed to keep the people at bay. It is amazing that in the face of all of the aggression used against them in their struggle for sovereignty that the Yaqui still exist today in Sonora, living life much as they have for millennia and maintaining their cultural institutions as they always have. The Yaqui language has even seen a revival in recent years as classes and schools have popped up to focus on the language. Despite everything the Yaquis have gone through it is quite evident that nothing can completely break the spirit of the Yaqui. The tribe, and the memory of the Yaqui Republic, live on.

to the Yucatán to work on plantations and many Yaquis did not survive the alien tropical climate or the harsh living and working conditions. The more troublesome members of the tribe were either executed or deported to faraway places such as the islands of the Caribbean or the nation of Bolivia in South America. In spite of all of this, the remaining Yaquis in Sonora continued to resist the Mexican government in one way or another. After the “last stand” of the Yaquis at what has been called the Battle of Cerro del Gallo in 1927, Mexico established armed garrisons in each village with a majority Yaqui population. This was a solution that seemed to keep the people at bay. It is amazing that in the face of all of the aggression used against them in their struggle for sovereignty that the Yaqui still exist today in Sonora, living life much as they have for millennia and maintaining their cultural institutions as they always have. The Yaqui language has even seen a revival in recent years as classes and schools have popped up to focus on the language. Despite everything the Yaquis have gone through it is quite evident that nothing can completely break the spirit of the Yaqui. The tribe, and the memory of the Yaqui Republic, live on.

REFERENCES USED (Not a formal bibliography)

“Biografía de José María Leyva Cajeme” In Obras históricas: Reseña histórica del Estado de Sonora by Ramón Corral (in Spanish)

Las razas indígenas de Sonora y la guerra del yaqui by Fortunato Hernández (in Spanish)

Yaqui Resistance and Survival: The Struggle for Land and Autonomy, 1821-1910 by Evelyn Hu-DeHart

Yaqui Myths and Legends by Ruth Warner Giddings

3 thoughts on “Cajemé and the Yaqui Indian Republic”

A very interesting read, I didn’t know this I was told other things about the yaquis, I am a yaqui tarumara but know nothing about my ancestors, I was born in Magdalena Sonora but left young so I had no time to study

Thanks for stopping by. I hope my material helped in some way.

My paternal family are from Guaymas, Sonora. My DNA shows 33% indigenous native. I have traced my family tree back to my paternal great grandfather, Jesus Bermudes, who was born in Santa Barbara, CA in 1829. I aware that the state of Sonora almost became part of the U.S.