Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

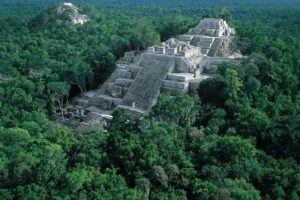

The date was December 29, 1931. A 24-year-old American botanist named Cyrus Lundell was flying in a small aircraft from the City of Campeche to his new assignment in Belize City, a sleepy Caribbean town in what was then British Honduras. Lundell was an assistant physiologist with the Tropical Plant Research Foundation based in Washington, DC. The foundation sent the young botanist to British Honduras to assist with experiments involving the sapodilla tree, which yields chicle, then used for making chewing gum. While flying above what seemed like endless jungle somewhere over the eastern part of the Mexican state of Campeche, Lundell noticed massive buildings peeking out of the forest canopy. He noted the coordinates and passed them along to academics interested in Maya ruins. Sylvanus G. Morely of the Carnegie Institution who was down at Chichén Itzá at the time took great interest in the ruins as they had not previously been reported by anyone to date. Morely would later lead an expedition to the site in 1932. The reason why no one knew of this place before is because the ancient city was almost 100 miles away from the nearest town in the middle of the largest expanse of tropical forest in the Americas outside the Amazon. No one owned the land on which the ruins stood. No Spaniard in colonial history or contemporary Maya had been to this no-man’s land just north of the invisible border with Guatemala. Morely and his crew mapped the tree-enshrouded city which seemed to go on and on, disappearing into the impenetrable vegetation. Although Morely and his team were the first to visit the ruins, the honor of naming this true “lost city” went to Cyrus Lundell who spotted it first from the window of his plane. He decided to call the site “Calakmul,” which is a combination of three Maya words: ca, which means, “two”; lak, meaning, “adjacent”; and mul, which means “pyramid” or “artificial mound.” So, Ca-lak-mul then means “The place of the two side-by-side pyramids.”

The date was December 29, 1931. A 24-year-old American botanist named Cyrus Lundell was flying in a small aircraft from the City of Campeche to his new assignment in Belize City, a sleepy Caribbean town in what was then British Honduras. Lundell was an assistant physiologist with the Tropical Plant Research Foundation based in Washington, DC. The foundation sent the young botanist to British Honduras to assist with experiments involving the sapodilla tree, which yields chicle, then used for making chewing gum. While flying above what seemed like endless jungle somewhere over the eastern part of the Mexican state of Campeche, Lundell noticed massive buildings peeking out of the forest canopy. He noted the coordinates and passed them along to academics interested in Maya ruins. Sylvanus G. Morely of the Carnegie Institution who was down at Chichén Itzá at the time took great interest in the ruins as they had not previously been reported by anyone to date. Morely would later lead an expedition to the site in 1932. The reason why no one knew of this place before is because the ancient city was almost 100 miles away from the nearest town in the middle of the largest expanse of tropical forest in the Americas outside the Amazon. No one owned the land on which the ruins stood. No Spaniard in colonial history or contemporary Maya had been to this no-man’s land just north of the invisible border with Guatemala. Morely and his crew mapped the tree-enshrouded city which seemed to go on and on, disappearing into the impenetrable vegetation. Although Morely and his team were the first to visit the ruins, the honor of naming this true “lost city” went to Cyrus Lundell who spotted it first from the window of his plane. He decided to call the site “Calakmul,” which is a combination of three Maya words: ca, which means, “two”; lak, meaning, “adjacent”; and mul, which means “pyramid” or “artificial mound.” So, Ca-lak-mul then means “The place of the two side-by-side pyramids.”

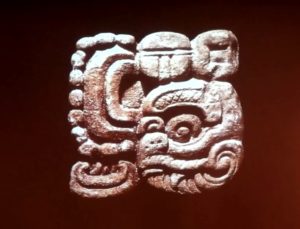

At the time of its discovery, no one knew how to read ancient Maya glyphs and no one could recognize the city’s glyph if they did discover it. We know now that the ancient Maya called the core of the city Ox Te’ Tuun, which loosely translates to “The Place of the Three Stones.” The larger kingdom that Calakmul ruled over may have been called Chiik Naab’. This is a phonetic reading of an ancient Maya glyph which may have been associated with the greater Kingdom of Calakmul. No one has yet been able to figure out the meaning of the name Chiik Naab‘. There is also a snake-headed name glyph associated with the ruling dynasty of Calakmul, the Kaan family. In the 1990s Calakmul was dubbed “The Snake Kingdom” by some researchers because of this dynastic glyph. The reach of the Kaan family was so great and the kingdom so powerful, the snake headed name symbol has a greater distribution throughout the ancient Maya world than any other emblem glyph. This colossal city, first made known to the outside world only in the 1930s, was the center of one of the most powerful kingdoms in the history of ancient Mexico.

At the time of its discovery, no one knew how to read ancient Maya glyphs and no one could recognize the city’s glyph if they did discover it. We know now that the ancient Maya called the core of the city Ox Te’ Tuun, which loosely translates to “The Place of the Three Stones.” The larger kingdom that Calakmul ruled over may have been called Chiik Naab’. This is a phonetic reading of an ancient Maya glyph which may have been associated with the greater Kingdom of Calakmul. No one has yet been able to figure out the meaning of the name Chiik Naab‘. There is also a snake-headed name glyph associated with the ruling dynasty of Calakmul, the Kaan family. In the 1990s Calakmul was dubbed “The Snake Kingdom” by some researchers because of this dynastic glyph. The reach of the Kaan family was so great and the kingdom so powerful, the snake headed name symbol has a greater distribution throughout the ancient Maya world than any other emblem glyph. This colossal city, first made known to the outside world only in the 1930s, was the center of one of the most powerful kingdoms in the history of ancient Mexico.

How did this powerful kingdom come to be? In addition to being one of the largest and most formidable of the ancient Maya kingdoms, Calakmul was one of the longest-lasting. Ongoing research is still filling in the blanks of the city-state’s early years, but researchers are certain that Calakmul first emerged as a small town sometime in the early Preclassic Period. That would put the city’s founding at around 400 BC. Some scholars call this the time period the Epi-Olmec Era because the much older Olmec civilization was well into its decline in the first few centuries BC. Archaeologists are divided on what they believe the Olmecs’ influence was on the founding of Calakmul, but some of the early art and architecture show an Olmec influence. The city was located near what modern-day Mexicans call a bajo, a low-lying area that turns into a marsh after the rains. These low-lying semi-wetlands have fertile soils for planting, so the setting would have been ideal for farming. In addition, near the bajo are rich flint deposits. In those early centuries BC, those deposits were quarried, and the flint was fashioned into arrowheads and other items that were most likely produced in a surplus and traded with surrounding communities or long-distance traders. The network of roads or sacbes, fan out from the Calakmul’s core and some archaeologists believe these roads may have linked the city with the larger and more powerful ancient Maya sites of El Mirador, Nakbe and El Tintal in the Preclassic period. So, essentially, Calakmul started off as a center of agriculture and commerce and grew from there.

There are many inscriptions throughout the city that tell people of the modern world the history of this magnificent place. The first record at Calakmul of the enthronement of a king is found on a stone monolith, or stela, and dates to 411 AD. Archaeologists have pieced together a dynastic record from the 117 stelae at the site and from references to Calakmul rulers throughout the city on other monuments as well as on monuments in other Maya cities. In the early 500s there appears to have been rulers of Calakmul who were not of local royal households, leading some to believe that the city, for about a century was ruled by foreigners or local military leaders. Sometime in the mid-500s AD the Kaan family relocated to Calakmul, possibly from the older kingdom of El Mirador which was linked by trade and had a political relationship with Calakmul. Perhaps for the first few centuries AD Calakmul was either allied with or was a subject state of El Mirador and when Calakmul started to rise and El Mirador’s importance started to wane, the royal family of Kaan moved its court to Calakmul and made it the capital of the greater “Snake Kingdom.” The Kaan dynasty at Calakmul produced a series of strong rulers with interesting names. Among them were Great Serpent, Split Earth, First Wielder of the Ax, Smoking Jaguar Paw and Sky Witness. In the Maya language, the rulers’ names were preceded by their formal title known as k’uhul kan ajawob. This translates to “Divine Lord of the Kingdom of the Snakes.”

There are many inscriptions throughout the city that tell people of the modern world the history of this magnificent place. The first record at Calakmul of the enthronement of a king is found on a stone monolith, or stela, and dates to 411 AD. Archaeologists have pieced together a dynastic record from the 117 stelae at the site and from references to Calakmul rulers throughout the city on other monuments as well as on monuments in other Maya cities. In the early 500s there appears to have been rulers of Calakmul who were not of local royal households, leading some to believe that the city, for about a century was ruled by foreigners or local military leaders. Sometime in the mid-500s AD the Kaan family relocated to Calakmul, possibly from the older kingdom of El Mirador which was linked by trade and had a political relationship with Calakmul. Perhaps for the first few centuries AD Calakmul was either allied with or was a subject state of El Mirador and when Calakmul started to rise and El Mirador’s importance started to wane, the royal family of Kaan moved its court to Calakmul and made it the capital of the greater “Snake Kingdom.” The Kaan dynasty at Calakmul produced a series of strong rulers with interesting names. Among them were Great Serpent, Split Earth, First Wielder of the Ax, Smoking Jaguar Paw and Sky Witness. In the Maya language, the rulers’ names were preceded by their formal title known as k’uhul kan ajawob. This translates to “Divine Lord of the Kingdom of the Snakes.”

The Kaan family expanded their realm, consolidated their power and wealth, and by the middle of the 6th Century AD, Calakmul came up against another Maya superpower in the region, the great city of Tikal in the south. Calakmul made alliances with the towns and cities surrounding Tikal, thus trying to squeeze out the city, cutting off its resources and opportunities for long-distance trade. In the year 648 AD Calakmul won an overwhelming victory against Tikal at the city of Dos Pilas on the shores of the La Pasión River. Dos Pilas was founded by Tikal just 19 years earlier. They installed a 4-year-old boy from a Tikal noble family as the new city’s ruler and the city grew rapidly as a center of commerce. Dos Pilas was 70 miles away from Calakmul, well within the territory of Tikal, and the Kaan family made the city one of the largest military bases in the newly annexed lands of the Snake Kingdom. The powerful Kaan rulers were not able to extinguish Tikal completely, though, and in the year 695 Tikal came back with a vengeance and defeated Calakmul in a major battle. This was followed by 50 years of Tikal winning small battles against Calakmul, slowly gaining back its former territory and its former allies. The royal family of Tikal had strong ties of blood and trade to the central Mexican powerhouse Teotihuacán hundreds of miles away. Some scholars believe that in the late 600s Tikal got help from Teotihuacán to defeat Calakmul, thus preserving Teotihuacán’s economic interests in the region. One can only imagine warriors from the temperate climate of the Basin of Mexico fighting in the steamy jungles of the Maya area some 800 miles from home. After the major defeat of Calakmul by Tikal in 695 the kingdoms  coexisted without conflict for 25 years until their rivalry became “hot” again in the year 720. The ruler of the city of Quiriguá who paid tribute to the king of Copán decided to revolt against the Copán king to make Quiriguá an independent kingdom. The revolution in Quiriguá was successful, at which time Calakmul moved in and offered Quiriguá the status of protectorate within the greater Snake Kingdom. Copán was always the historic ally of Tikal and when one of its former territories – the city of Quiriguá with over 16,000 people – declared its loyalty to a sworn enemy, Tikal attacked Calakmul’s territory. This last round of warfare ended in the year 744 after the capture of two major Calakmul cities: El Peru and Naranjo.

coexisted without conflict for 25 years until their rivalry became “hot” again in the year 720. The ruler of the city of Quiriguá who paid tribute to the king of Copán decided to revolt against the Copán king to make Quiriguá an independent kingdom. The revolution in Quiriguá was successful, at which time Calakmul moved in and offered Quiriguá the status of protectorate within the greater Snake Kingdom. Copán was always the historic ally of Tikal and when one of its former territories – the city of Quiriguá with over 16,000 people – declared its loyalty to a sworn enemy, Tikal attacked Calakmul’s territory. This last round of warfare ended in the year 744 after the capture of two major Calakmul cities: El Peru and Naranjo.

Although most of its time and effort was spent battling its southern neighbor, Calakmul did have rivals with other Maya kingdoms besides Tikal. On April 23, 599 AD Calakmul attacked the city of Palenque and defeated its queen, Lady Yohl Ik’nal. Possibly out of respect for Lady Yohl Ik’nal’s fine lineage, the Kaan family of Calakmul allowed the Palenque queen to remain on the throne for several years after the defeat, although the great lady paid tribute to her new faraway overlords. Thirteen years later, Calakmul again sacked Palenque after the queen’s successor King Ajen Yohl Mat stopped paying tribute to Calakmul. The Calakmul invasion force killed the king and another prominent member of the Palenque nobility, a man named Janab Pakal. The city of Palenque never recovered. Archaeologists believe that the Kaan family of Calakmul had no interest in governing the city of Palenque, they just wanted control of the lucrative trade routes Palenque had dominated in the western Maya region. Besides the major wars with Tikal and Palenque, Calakmul also had many skirmishes with tiny Maya kingdoms that were either independent or allied with the major powers. Calakmul also put down minor rebellions within its own realm, as some cities and towns did not like living under the Kaan dynasty. After the last war with Tikal in 744 AD, Calakmul started to decline. Fewer and fewer monuments were built and fewer carvings were made with dates on them. The kingdom had pretty much collapsed by the beginning of the 800s with the last date inscription at the city of Calakmul reading 909 AD. The grandeur gone along with the royal family and everything else, the city was left to squatters and eventually fell to ruin. As mentioned earlier, not even the descendants of the ancient Maya knew of Calakmul’s existence in the 20th Century because the site and surrounding territories had become so overcome with jungle.

Today, the ruined city of Calakmul is a precious time capsule of Classic Maya civilization. Because it was not known to the Spanish or any modern-day people, the city was not looted and was as the people left it when Sylvanus Morely did his first investigations of Calakmul in the 1930s. After its initial exploration, the city was left untouched again until 1982 when the Autonomous University of Campeche began a series of intense research projects at site which lasted until 1994. It was during this 12-year period that 6,250 structures were mapped in an 8 square mile area to include pyramids, the royal residences of the Kaans, temples, the 110 stelae previously mentioned and many other buildings. A series of tunnels were also discovered running underneath the main acropolis at the site. In the late 1990s, recognizing the importance of the wealth of information to be found at Calakmul, the National Institute of Anthropology and History out of Mexico City started permanent, large-scale research at Calakmul under the direction of esteemed Mexican archaeologist Ramón Carrasco. In the year 2002, UNESCO incorporated the ruins into a World Heritage Site called “Ancient Maya City and Protected Tropical Forests of Calakmul, Campeche” to further aid in the conservation and research efforts. With research here increased, archaeologists are making important discoveries at Calakmul on a weekly basis. As most of the capital city of the Kingdom of the Snake is yet unexplored, no one really knows what mysteries are left to be solved with further exploration of this classic “lost city” of the ancient Maya.

Today, the ruined city of Calakmul is a precious time capsule of Classic Maya civilization. Because it was not known to the Spanish or any modern-day people, the city was not looted and was as the people left it when Sylvanus Morely did his first investigations of Calakmul in the 1930s. After its initial exploration, the city was left untouched again until 1982 when the Autonomous University of Campeche began a series of intense research projects at site which lasted until 1994. It was during this 12-year period that 6,250 structures were mapped in an 8 square mile area to include pyramids, the royal residences of the Kaans, temples, the 110 stelae previously mentioned and many other buildings. A series of tunnels were also discovered running underneath the main acropolis at the site. In the late 1990s, recognizing the importance of the wealth of information to be found at Calakmul, the National Institute of Anthropology and History out of Mexico City started permanent, large-scale research at Calakmul under the direction of esteemed Mexican archaeologist Ramón Carrasco. In the year 2002, UNESCO incorporated the ruins into a World Heritage Site called “Ancient Maya City and Protected Tropical Forests of Calakmul, Campeche” to further aid in the conservation and research efforts. With research here increased, archaeologists are making important discoveries at Calakmul on a weekly basis. As most of the capital city of the Kingdom of the Snake is yet unexplored, no one really knows what mysteries are left to be solved with further exploration of this classic “lost city” of the ancient Maya.

REFERENCES

Drew, David. The Lost Chronicles of the Maya Kings. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1999. We are Amazon affiliates. Buy the book on Amazon here: https://amzn.to/3q9DC8F

Sharer, Robert J. and Loa P. Trader. The Ancient Maya. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2006.We are Amazon affiliates. Buy the book on Amazon here: https://amzn.to/2VcNyjD

UNESCO web site