Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

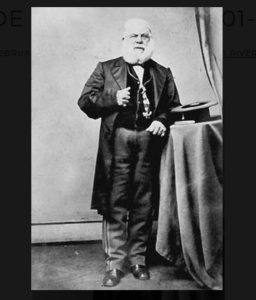

On July 15, 2021, the Los Angeles Times ran a column titled “Does Larry Elder Have a Path to the Governor’s Office? Maybe, if Democrats Don’t Turn Out.” The California “paper of record,” was entertaining the idea that the conservative African American talk show host might have a good chance at being California’s next governor if Governor Gavin Newsom is ousted in the September 2021 recall election. The esteemed newspaper went on to say that Elder, “would be California’s first Black governor.” The Capitol Journal Columnist who wrote the column, George Skelton, failed to do his homework. California has already had a Black governor, elected twice, once in 1832 and again in 1845. The election of this person to the highest office in California happened under Mexican rule and that first Black governor’s name was Pío Pico, and Afro-Mexican.

Pío Pico was born on May 5, 1801, at the Misión San Gabriel Arcángel in what was then known as New Spain’s province of Las Californias, called Alta California 3 years later. As an interesting aside, the midwife attending to Pío Pico’s birth was Eulalia Pérez de Guillén Mariné, who died in 1878 at the age of 112, thus making her the oldest known person who has ever lived in California and one of the oldest people to have ever lived in the history of the United States. Although living in a backwater of the Spanish Empire, the Pico family had carved out a special place for themselves in this remote land. Pico’s grandfather, Santiago de la Cruz Pico, first came to the Californias in 1775 with the Juan Bautista de Anza expedition overland through what is now the Mexican state of Sonora and the US state of Arizona. This was just 6 years after the first permanent Spanish settlement was established in Alta California at San Diego on the Pacific Coast in 1769. The viceroy of New Spain and the King of Spain himself were both watching this expedition carefully as the Spanish feared Russian colonization of the Californias and wanted to legitimize Spain’s claim over this vast territory. In 1777 Santiago Pico settled in San Diego. His wife, María Jacinta de la Bastida, was listed in the 1790 census as mulata, which indicates that she was of half African descent and half European descent. Some researchers believe that she may have been full African and was listed as mulata for social considerations. Santiago Pico was mixed race of unknown heritage and classified as mestizo on that 1790 census. Researchers believe that he also had strong African roots.

Pío Pico was born on May 5, 1801, at the Misión San Gabriel Arcángel in what was then known as New Spain’s province of Las Californias, called Alta California 3 years later. As an interesting aside, the midwife attending to Pío Pico’s birth was Eulalia Pérez de Guillén Mariné, who died in 1878 at the age of 112, thus making her the oldest known person who has ever lived in California and one of the oldest people to have ever lived in the history of the United States. Although living in a backwater of the Spanish Empire, the Pico family had carved out a special place for themselves in this remote land. Pico’s grandfather, Santiago de la Cruz Pico, first came to the Californias in 1775 with the Juan Bautista de Anza expedition overland through what is now the Mexican state of Sonora and the US state of Arizona. This was just 6 years after the first permanent Spanish settlement was established in Alta California at San Diego on the Pacific Coast in 1769. The viceroy of New Spain and the King of Spain himself were both watching this expedition carefully as the Spanish feared Russian colonization of the Californias and wanted to legitimize Spain’s claim over this vast territory. In 1777 Santiago Pico settled in San Diego. His wife, María Jacinta de la Bastida, was listed in the 1790 census as mulata, which indicates that she was of half African descent and half European descent. Some researchers believe that she may have been full African and was listed as mulata for social considerations. Santiago Pico was mixed race of unknown heritage and classified as mestizo on that 1790 census. Researchers believe that he also had strong African roots.

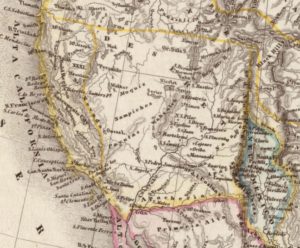

By the time Pío Pico was born in the San Gabriel Valley in what is now Los Angeles County, the Pico family had already amassed wealth and prestige. Pío Pico’s father, José Dario María Pico was stationed at the Presidio of San Diego and in 1798, he became a corporal of guard at Mission San Luis Rey de Francia in the modern-day city of Oceanside, California. Pío’s father then returned to the San Gabriel Valley where he served at the presidio until his death in 1819. After his father’s death, the 18-year-old Pío returned to San Diego. In 1821, just two years after his move back to San Diego, New Spain gained its independence from Spain and Alta California became a far-flung territory of the new nation of Mexico. There was great optimism and hope for the future in California at the time, and throughout most of the 1820s the central government in Mexico City left the Californios alone to rule themselves. During this time Pío Pico had a prosperous business in San Diego selling groceries, liquor, furniture, shoes, and mules. Pico’s business interests took him to various parts of Alta and Baja California, and on his various buying and selling trips he networked with many influential people. In 1826, he was elected to the Diputación, a legislature that served as a kind of advisory board to the Mexican governor of Alta California. He would be elected to the Diputación several more times and in 1829 he received his first land grant from the Mexican government, almost 9,000 acres in the eastern part of the modern-day County of San Diego, California. In 1832, after a mini revolt in the province, the Diputación elected Pío Pico governor of California. He replaced Manuel Victoria, who had been appointed to rule California by a Mexico City bureaucrat, the Minister of Interior and Exterior Relations, Lucas Alamán. The local Californios wanted democratic reforms and more autonomy. The brief 20-day governorship of Pío Pico restored order and two men were appointed to rule over the northern and southern parts of Alta California until Mexico City sent a new governor in 1833, a general in the Mexican Army named José Figueroa. Under the new governor, the California missions were secularized, and land was parceled into ranchos and sold off to private citizens. Various members of the Pico family bought up the newly available land. In 1834 Pío Pico ran for mayor of San Diego but he was defeated.

By the time Pío Pico was born in the San Gabriel Valley in what is now Los Angeles County, the Pico family had already amassed wealth and prestige. Pío Pico’s father, José Dario María Pico was stationed at the Presidio of San Diego and in 1798, he became a corporal of guard at Mission San Luis Rey de Francia in the modern-day city of Oceanside, California. Pío’s father then returned to the San Gabriel Valley where he served at the presidio until his death in 1819. After his father’s death, the 18-year-old Pío returned to San Diego. In 1821, just two years after his move back to San Diego, New Spain gained its independence from Spain and Alta California became a far-flung territory of the new nation of Mexico. There was great optimism and hope for the future in California at the time, and throughout most of the 1820s the central government in Mexico City left the Californios alone to rule themselves. During this time Pío Pico had a prosperous business in San Diego selling groceries, liquor, furniture, shoes, and mules. Pico’s business interests took him to various parts of Alta and Baja California, and on his various buying and selling trips he networked with many influential people. In 1826, he was elected to the Diputación, a legislature that served as a kind of advisory board to the Mexican governor of Alta California. He would be elected to the Diputación several more times and in 1829 he received his first land grant from the Mexican government, almost 9,000 acres in the eastern part of the modern-day County of San Diego, California. In 1832, after a mini revolt in the province, the Diputación elected Pío Pico governor of California. He replaced Manuel Victoria, who had been appointed to rule California by a Mexico City bureaucrat, the Minister of Interior and Exterior Relations, Lucas Alamán. The local Californios wanted democratic reforms and more autonomy. The brief 20-day governorship of Pío Pico restored order and two men were appointed to rule over the northern and southern parts of Alta California until Mexico City sent a new governor in 1833, a general in the Mexican Army named José Figueroa. Under the new governor, the California missions were secularized, and land was parceled into ranchos and sold off to private citizens. Various members of the Pico family bought up the newly available land. In 1834 Pío Pico ran for mayor of San Diego but he was defeated.

The 1830s were a tumultuous time for the Mexican territory of Alta California. Many of the local Californios were disgruntled with presidents and other government officials trying to rule them from faraway Mexico City. In the early decades of Spanish rule at the end of the 1700s, the area enjoyed a high degree of autonomy. Local affairs were handled locally with occasional military or clerical interference. The new nation of Mexico wanted to exert its sovereignty and secure its territory, and sparsely populated California was coveted by the Russians, the Americans and even the British. Mexico City had a difficult time asserting itself in this distant land inhabited by a fiercely independent people. In 1836, the 7th governor of Alta California, Mariano Chico, was run out of the country by the dissatisfied Californios. The national government in Mexico City headed by Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna appointed to the post of Alta California governor the military commandant of Mexican forces in the territory, a man named Nicolás Gutiérrez. This governor was also run out of the country by a group of locals, including Pío Pico, who were sympathetic to California’s independence. This latest coup was led by a 27-year-old customs inspector from Monterey named Juan Bautista Alvarado. Alvarado drafted a new constitution for a new nation, but eventually made peace with the authorities in Mexico City and was appointed governor, a post he would hold until 1842. Hearing rumors of a possible revolt in California, President Santa Anna sent 300 troops to the territory in January of 1842 under the command of Brigadier General Manuel Micheltorena with the intent of re-establishing a firmer and more direct rule from Mexico City. The 300 troops were mostly comprised of recently released convicts and the Brigadier General could not control them. Also, the Mexican government had not properly outfitted the troops, so they looted and pillaged for what they needed or wanted in their march across California. Needless to say, the military governor was not well liked. Former rebel Juan Bautista Alvarado returned to the political arena and with many prominent Californios he staged revolts in all major California cities and towns, driving Micheltorena back to Mexico City. It was at this moment in 1845 that Pío Pico was once again elected governor of California, as he was already the leader of the California Assembly. One of his first acts of governor was to move the capital from Monterey to Los Angeles. This was a year before the Mexican War began and Governor Pico sensed the tension brewing with the United States. Pico and others believed that war with the Americans was bound to happen. At one point Governor Pico declared that he would swear an oath of loyalty to Queen Victoria and have California become part of the British Empire. Perhaps he felt that rule from faraway London would give the Californios the autonomy they craved and the protection against an inevitable American takeover.

The 1830s were a tumultuous time for the Mexican territory of Alta California. Many of the local Californios were disgruntled with presidents and other government officials trying to rule them from faraway Mexico City. In the early decades of Spanish rule at the end of the 1700s, the area enjoyed a high degree of autonomy. Local affairs were handled locally with occasional military or clerical interference. The new nation of Mexico wanted to exert its sovereignty and secure its territory, and sparsely populated California was coveted by the Russians, the Americans and even the British. Mexico City had a difficult time asserting itself in this distant land inhabited by a fiercely independent people. In 1836, the 7th governor of Alta California, Mariano Chico, was run out of the country by the dissatisfied Californios. The national government in Mexico City headed by Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna appointed to the post of Alta California governor the military commandant of Mexican forces in the territory, a man named Nicolás Gutiérrez. This governor was also run out of the country by a group of locals, including Pío Pico, who were sympathetic to California’s independence. This latest coup was led by a 27-year-old customs inspector from Monterey named Juan Bautista Alvarado. Alvarado drafted a new constitution for a new nation, but eventually made peace with the authorities in Mexico City and was appointed governor, a post he would hold until 1842. Hearing rumors of a possible revolt in California, President Santa Anna sent 300 troops to the territory in January of 1842 under the command of Brigadier General Manuel Micheltorena with the intent of re-establishing a firmer and more direct rule from Mexico City. The 300 troops were mostly comprised of recently released convicts and the Brigadier General could not control them. Also, the Mexican government had not properly outfitted the troops, so they looted and pillaged for what they needed or wanted in their march across California. Needless to say, the military governor was not well liked. Former rebel Juan Bautista Alvarado returned to the political arena and with many prominent Californios he staged revolts in all major California cities and towns, driving Micheltorena back to Mexico City. It was at this moment in 1845 that Pío Pico was once again elected governor of California, as he was already the leader of the California Assembly. One of his first acts of governor was to move the capital from Monterey to Los Angeles. This was a year before the Mexican War began and Governor Pico sensed the tension brewing with the United States. Pico and others believed that war with the Americans was bound to happen. At one point Governor Pico declared that he would swear an oath of loyalty to Queen Victoria and have California become part of the British Empire. Perhaps he felt that rule from faraway London would give the Californios the autonomy they craved and the protection against an inevitable American takeover.

War did come and Pío Pico became part of new controversies. Pico took $14,000 from the sale of former mission lands in the San Fernando Valley and claimed he would use the proceeds to help Mexico fight the United States in the Mexican War, but there was no accounting for what happened to the money. During most of the fighting Governor Pico was not even in Alta California. He went to Baja California to plead for more troops and left his brother Andrés, who was a Mexican army officer, in charge of the crumbling government. As they could not spare any additional troops, authorities in Mexico City ordered Pío Pico to stay in Sonora during the remainder of the conflict.

War did come and Pío Pico became part of new controversies. Pico took $14,000 from the sale of former mission lands in the San Fernando Valley and claimed he would use the proceeds to help Mexico fight the United States in the Mexican War, but there was no accounting for what happened to the money. During most of the fighting Governor Pico was not even in Alta California. He went to Baja California to plead for more troops and left his brother Andrés, who was a Mexican army officer, in charge of the crumbling government. As they could not spare any additional troops, authorities in Mexico City ordered Pío Pico to stay in Sonora during the remainder of the conflict.

The Americans won the war and Pío Pico returned to his native land as a private citizen. Part of the Treaty of Cahuenga signed by Andrés Pico that ended the fighting in California was also folded into the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo that ended the Mexican War and guaranteed full citizenship and property rights to all former citizens of Mexico residing in all lands ceded to the United States. Pío Pico who had vast land holdings numbering into the tens of thousands of acres and many business interests was allowed to keep his commercial empire.

Under American rule, the first Black governor of California flourished. During the 1849 California Gold Rush, the Pico ranches supplied beef to the mining camps. Other Pico-owned businesses provided for the needs of the booming population in northern California. In 1850 Pío Pico purchased the 8,894-acre Rancho Paso de Bartolo which now makes up half of the city of Whittier, California, and built a lavish house there. Throughout the 1860s and 1870s Pico invested in many businesses, including the Los Angeles Petroleum  Refining Company, the city’s first commercial oil company. In 1870 he built the first three-story building in Los Angeles, the Casa Pico Hotel. At the height of his financial empire Pío Pico owned over a half million acres of land but this was not without its share of headaches. He was constantly in court over property disputes and logged over 100 lawsuits through the California legal system. In addition to being very generous with family and friends, Pío Pico enjoyed high stakes gambling and was often on the hook to loan sharks. As he did not speak or write English, Pico was often the victim of fraud. In the 1880s, and specifically after the flood of 1883, he started to have serious financial problems. The final nail in the coffin was a swindle perpetrated in 1891 by Bernard Cohn, a petty Los Angeles wool merchant who had become wealthy buying up properties and businesses for song. Pío Pico thought he was signing a mortgage for $60,000 on his remaining California land holdings, but instead it was a straight bill of sale. Pico fought and lost in court, used the $60,000 to pay off debts and lived his final years penniless on the charity of family and friends who remembered his generosity and public service from previous years. The first Black governor of California died peacefully in the home of one of his daughters, Joaquina Pico Moreno, in Los Angeles at the age of 93, after witnessing and molding much history, under three flags, leaving behind an incredible legacy.

Refining Company, the city’s first commercial oil company. In 1870 he built the first three-story building in Los Angeles, the Casa Pico Hotel. At the height of his financial empire Pío Pico owned over a half million acres of land but this was not without its share of headaches. He was constantly in court over property disputes and logged over 100 lawsuits through the California legal system. In addition to being very generous with family and friends, Pío Pico enjoyed high stakes gambling and was often on the hook to loan sharks. As he did not speak or write English, Pico was often the victim of fraud. In the 1880s, and specifically after the flood of 1883, he started to have serious financial problems. The final nail in the coffin was a swindle perpetrated in 1891 by Bernard Cohn, a petty Los Angeles wool merchant who had become wealthy buying up properties and businesses for song. Pío Pico thought he was signing a mortgage for $60,000 on his remaining California land holdings, but instead it was a straight bill of sale. Pico fought and lost in court, used the $60,000 to pay off debts and lived his final years penniless on the charity of family and friends who remembered his generosity and public service from previous years. The first Black governor of California died peacefully in the home of one of his daughters, Joaquina Pico Moreno, in Los Angeles at the age of 93, after witnessing and molding much history, under three flags, leaving behind an incredible legacy.

REFERENCES

July 15, 2021, Los Angeles Times column titled “Does Larry Elder Have a Path to the Governor’s Office? Maybe, if Democrats Don’t Turn Out.”

Salomon, Carlos Manuel. Pío Pico: The Last Governor of Mexican California. Oklahoma City: University of Oklahoma Press, 2010. We are Amazon affiliates. Buy the book on Amazon here: https://amzn.to/3CxJLSu