Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

Six years before assisting Father Eusebio Kino with evangelizing the O’odham peoples of what is now the American Southwest and northern Mexico, a young army officer arrived in New Spain. His name was Juan Mateo Mange and the year was 1693. Born in Aragón, the young Spanish military man was following in the footsteps of his uncle, a man known to history as General Jirozna, who had been dispatched to the Americas many years before. After hearing stories of the New World for quite some time, Mange could not believe that he was actually in this unknown, almost magical place, and that he was exploring previously uncharted territories in the northern desert regions of Spain’s empire in New World. In 1694, just a year into his deployment, Juan Mateo Mange would stumble upon something that would baffle researchers for centuries to come. Near the banks of the intermittently flowing Rio Concepción, Mange noticed a hill with some unusual structures on its sides. Getting a closer look, he would later note in his detailed diaries that he had come upon a gigantic ruined city in the middle of one of the world’s harshest deserts. The structures on the side of the hill looked like trenches to the young military officer, so he christened the place Cerro de Trincheras, or “Hill of Trenches” in English, a name that survives over three centuries later. Although the city had been abandoned for many years before its rediscovery by Mange, the young Spaniard assumed that the ruined city’s previous inhabitants must have been a warlike race to have created so many fortified and defensive trenches on the hill. Like so many other conquistadors who perceived no or little value of a place, Juan Mateo Mange moved on. He would describe this strange, abandoned city many years later in his book, Luz de Tierra Incógnita, or “Light of the Unknown Land,” which was received well in Spain.

Six years before assisting Father Eusebio Kino with evangelizing the O’odham peoples of what is now the American Southwest and northern Mexico, a young army officer arrived in New Spain. His name was Juan Mateo Mange and the year was 1693. Born in Aragón, the young Spanish military man was following in the footsteps of his uncle, a man known to history as General Jirozna, who had been dispatched to the Americas many years before. After hearing stories of the New World for quite some time, Mange could not believe that he was actually in this unknown, almost magical place, and that he was exploring previously uncharted territories in the northern desert regions of Spain’s empire in New World. In 1694, just a year into his deployment, Juan Mateo Mange would stumble upon something that would baffle researchers for centuries to come. Near the banks of the intermittently flowing Rio Concepción, Mange noticed a hill with some unusual structures on its sides. Getting a closer look, he would later note in his detailed diaries that he had come upon a gigantic ruined city in the middle of one of the world’s harshest deserts. The structures on the side of the hill looked like trenches to the young military officer, so he christened the place Cerro de Trincheras, or “Hill of Trenches” in English, a name that survives over three centuries later. Although the city had been abandoned for many years before its rediscovery by Mange, the young Spaniard assumed that the ruined city’s previous inhabitants must have been a warlike race to have created so many fortified and defensive trenches on the hill. Like so many other conquistadors who perceived no or little value of a place, Juan Mateo Mange moved on. He would describe this strange, abandoned city many years later in his book, Luz de Tierra Incógnita, or “Light of the Unknown Land,” which was received well in Spain.

The fact that this place was in the middle of a wasteland is what helped to save it. Located some 60 miles south southwest of the US-Mexico border at Nogales, no one really paid much attention to Cerro de Trincheras until the 1940s. In 1948, the head of the municipio, or county of Trincheras, a man named Edmundo Sierra Márquez, spoke out against the Sonora-Baja California Railroad Division for wanting to demolish the archaeological ruins. In the late 1940s, the railroad was starting to use the stones at Cerro de Trincheras in the construction of the train tracks of a new line. The locals petitioned the state authorities and then went to the federal government in Mexico City. This halted what would have been the wholesale destruction of the site and gave it a moderate degree of protection. Today the ruins are part of the only archaeological zone in the entire state of Sonora accessible to tourists. Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History, or INAH, opened the site to the public in 2011, only after years of research, restoration and on-site improvements. Modern-day archaeologists realized decades ago the importance of studying and preserving this place as it breaks the myths and presuppositions of an empty northern desert that was either uninhabitable or home to scraggly bands of nomads barely eking out an existence in a cruel environment.

The fact that this place was in the middle of a wasteland is what helped to save it. Located some 60 miles south southwest of the US-Mexico border at Nogales, no one really paid much attention to Cerro de Trincheras until the 1940s. In 1948, the head of the municipio, or county of Trincheras, a man named Edmundo Sierra Márquez, spoke out against the Sonora-Baja California Railroad Division for wanting to demolish the archaeological ruins. In the late 1940s, the railroad was starting to use the stones at Cerro de Trincheras in the construction of the train tracks of a new line. The locals petitioned the state authorities and then went to the federal government in Mexico City. This halted what would have been the wholesale destruction of the site and gave it a moderate degree of protection. Today the ruins are part of the only archaeological zone in the entire state of Sonora accessible to tourists. Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History, or INAH, opened the site to the public in 2011, only after years of research, restoration and on-site improvements. Modern-day archaeologists realized decades ago the importance of studying and preserving this place as it breaks the myths and presuppositions of an empty northern desert that was either uninhabitable or home to scraggly bands of nomads barely eking out an existence in a cruel environment.

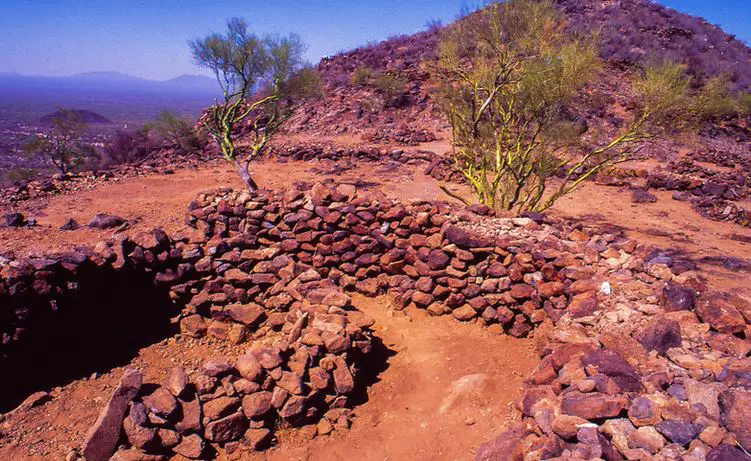

What the young Spanish army officer Juan Mateo Mange saw as trenches on the side of the hill in 1693 were really some 900 terraces that formed the core of the city. What is surprising is that to raise the walls of the terraces they placed one stone on top of another without using any type of mortar or “cement” to fix them. In the book, Entre muros de piedra or “Between Stone Walls,” in English, author Elisa Villalpando Canchola states that the ancient people of Cerro de Trincheras “may have built their houses in this open style that allows air circulation, since these characteristics are perfect for the climatic conditions of the Sonoran Desert.” The city saw its height between 1300 and 1450 AD, in the Late Pre-Hispanic period, occupying more than 100 hectares of surface area and standing about 170 meters above the level of the surrounding valley. Researchers believe that at its apex Cerro de Trincheras was home to approximately 1,500 people.

Archaeologists now believe that Cerro de Trincheras was part of a larger cultural complex that extended from what is now the central deserts of the Mexican state of Sonora to the southern parts of the US state of Arizona. Since the discovery by Mange in 1693 a handful of other much smaller similar sites have been found throughout Arizona and Sonora. Researchers have appropriately labeled this culture the Trincheras Culture and many believe it was an offshoot or sister culture to the Hohokam, the ancient inhabitants of the Salt and Gila River valleys of south-central Arizona. Author Alfred E. Johnson put forth a definition of Trincheras Culture in his 1963 journal article titled, “The Trincheras Culture of Northern Sonora” published in American Antiquity. The author states:

Archaeologists now believe that Cerro de Trincheras was part of a larger cultural complex that extended from what is now the central deserts of the Mexican state of Sonora to the southern parts of the US state of Arizona. Since the discovery by Mange in 1693 a handful of other much smaller similar sites have been found throughout Arizona and Sonora. Researchers have appropriately labeled this culture the Trincheras Culture and many believe it was an offshoot or sister culture to the Hohokam, the ancient inhabitants of the Salt and Gila River valleys of south-central Arizona. Author Alfred E. Johnson put forth a definition of Trincheras Culture in his 1963 journal article titled, “The Trincheras Culture of Northern Sonora” published in American Antiquity. The author states:

“This culture, which is associated with the drainages of the Magdalena and Altar rivers, is characterized by terraced hillside sites, rock corrals or enclosures, and a ceramic complex consisting of Trincheras purple-on-red and Trincheras polychrome pottery.”

Cerro de Trincheras is the largest site of this culture yet discovered. Researchers believe settlement began here in around 200 AD but the site only really became more complex over a thousand years later when the city’s population exploded. Around the year 1300, the occupants of this place built more than 900 terraces on the slopes of the hill, which looks much like a natural Mesoamerican pyramid. Most of the terraces measure from 13 to 30 meters long, although some measure more than three hundred meters long. Terrace width varies between 1.5 meters and 5 meters. On the terraces there are stone constructions with quadrangular and circular floor plans that reach up to a meter in height. Test excavations made in the floors of several of these terraces have yielded no household items or artifacts of any kind. The two most notable buildings at Cerro de Trincheras are called La Cancha and El Caracol. The first consists of a rectangle with rounded corners located at the base of the hill and seems to have functioned as a ritual space for community use. The second, located in the plaza to the east of the top, is a construction whose walls resemble a snail and is surrounded by circular structures. Its location, and the difficult access to it, suggest that it was a space reserved for a very small group of people. Researchers believe that El Caracol may have been either an elite residence or a place reserved for religious observances. Some archaeologists theorize that the entire site may have functioned as a place of pilgrimage with people coming to the hill much like their southern counterparts would visit temples and pyramids a thousand miles away. Many artisan workshops have been discovered at Cerro de Trincheras, and these workshops were primarily engaged in the creation of ceramics and jewelry manufacture. Some 25 different types of seashells have been found in the ruins of the city. These shells were brought in from the coast of the Gulf of California and here they were fashioned into beautiful objects for personal adornment such as necklaces, bracelets and rings. These items were most likely traded with neighboring peoples or along the long-distance trade routes that went all the way to the complex civilizations of the central part of ancient Mexico. Some Trinchera shell artifacts have been found at archaeological sites in northern Arizona and in New Mexico. There was also light manufacture of small stone items at Cerro de Trincheras. Archaeologists have uncovered many projectile points used in spears for hunting, as well as stone scrapers and choppers used in food preparation. The stone objects were made from locally sourced materials and were most likely made for local use only and were not traded. The inhabitants of Cerro de Trincheras also practiced the cultivation of corn, beans, squash, cotton, and maguey. Although mostly sedentary, the Trincheras people never completely abandoned their hunting and gathering way of life. Some members of households would go out into the desert far from the population center and bring back small game and other desert products, such as cactus fruits and fibers, for use inside the city.

There had to have been great order at Cerro de Trincheras as the city was built in the middle of a harsh environment. Mere survival must have been an ongoing struggle and must have required some sort of government or strict set of social norms. Very little is known about social stratification at Cerro de Trincheras or the life of the elite class here. Was the city ruled by a king? A priestly class? A council of elders? Some clues may be found in the burials discovered at the site, although research and interpretation are far from finished. In August 2008, when an excavation was being carried out to place an electrical power pole for the Cerro de Trincheras Visitors’ Center, an ancient cemetery was found, about 2 feet below the surface. This finding allowed the researchers to learn more about the rituals and funeral treatments given at the site. Unlike the Hohokam or neighboring cultures, the people at Cerro de Trincheras cremated their dead, except for infants who were buried intact. Besides the 4 sets of remains of the infants discovered, the Trincheras cemetery thus consisted of dozens of ceramic urns containing human remains. These urns were often surrounded by ceremonial objects or items deemed important to the deceased during their lifetimes. Some of the burial urns are quite decorative and elaborate and the uncovering of the cemetery in 2008 was quite a delightful surprise for archaeologists. Researchers are still trying to figure out a social structure for Cerro de Trincheras based on their findings at the cemetery. There are still many unknowns.

There had to have been great order at Cerro de Trincheras as the city was built in the middle of a harsh environment. Mere survival must have been an ongoing struggle and must have required some sort of government or strict set of social norms. Very little is known about social stratification at Cerro de Trincheras or the life of the elite class here. Was the city ruled by a king? A priestly class? A council of elders? Some clues may be found in the burials discovered at the site, although research and interpretation are far from finished. In August 2008, when an excavation was being carried out to place an electrical power pole for the Cerro de Trincheras Visitors’ Center, an ancient cemetery was found, about 2 feet below the surface. This finding allowed the researchers to learn more about the rituals and funeral treatments given at the site. Unlike the Hohokam or neighboring cultures, the people at Cerro de Trincheras cremated their dead, except for infants who were buried intact. Besides the 4 sets of remains of the infants discovered, the Trincheras cemetery thus consisted of dozens of ceramic urns containing human remains. These urns were often surrounded by ceremonial objects or items deemed important to the deceased during their lifetimes. Some of the burial urns are quite decorative and elaborate and the uncovering of the cemetery in 2008 was quite a delightful surprise for archaeologists. Researchers are still trying to figure out a social structure for Cerro de Trincheras based on their findings at the cemetery. There are still many unknowns.

Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History is expanding its Sonora Center and is devoting more resources toward understanding this complex archaeological site. Perhaps in the next few decades we will have a clearer picture of what happened here as Cerro de Trincheras yields its many mysteries.

REFERENCES

Johnson, Alfred E. “The Trincheras Culture of Northern Sonora.” American Antiquity, vol. 29, no. 2, 1963, pp. 174–86.

INAH Official website (in Spanish) https://www.inah.gob.mx/red-de-museos/280-zona-arqueologica-trincheras