Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

Nestled amid lush avocado groves in the western Mexican state of Michoacán, the archaeological site of Tingambato stands as a testament to the rich and complex history of pre-Hispanic civilizations. Known locally as Tinganio in the Purépecha language – a term that translates either to “the place where the fire ends” or “the place where the fire begins” – this site offers a glimpse into an era that predates the mighty Tarascan Empire. Flourishing between approximately AD 450 and 900, Tingambato represents a pivotal transitional period in Mesoamerican history, bridging the decline of the great Teotihuacan metropolis and the rise of regional powers in western Mexico. Unlike Teotihuacan with its grand pyramids or the iconic Chichén Itzá, Tingambato is a modest yet profoundly meaningful site. Its structures, influenced by distant cultural exchanges, reveal a blend of local traditions and external innovations. Spanning just a few hectares, the excavated area includes ceremonial platforms, a ball court, and intricate tombs that have yielded remarkable artifacts. Despite its significance, Tingambato remains underappreciated, drawing far fewer visitors than its more famous counterparts. This relative obscurity preserves its serene beauty and its hidden treasures, allowing explorers to wander through ancient pathways surrounded by verdant landscapes, evoking a sense of stepping back in time.

Nestled amid lush avocado groves in the western Mexican state of Michoacán, the archaeological site of Tingambato stands as a testament to the rich and complex history of pre-Hispanic civilizations. Known locally as Tinganio in the Purépecha language – a term that translates either to “the place where the fire ends” or “the place where the fire begins” – this site offers a glimpse into an era that predates the mighty Tarascan Empire. Flourishing between approximately AD 450 and 900, Tingambato represents a pivotal transitional period in Mesoamerican history, bridging the decline of the great Teotihuacan metropolis and the rise of regional powers in western Mexico. Unlike Teotihuacan with its grand pyramids or the iconic Chichén Itzá, Tingambato is a modest yet profoundly meaningful site. Its structures, influenced by distant cultural exchanges, reveal a blend of local traditions and external innovations. Spanning just a few hectares, the excavated area includes ceremonial platforms, a ball court, and intricate tombs that have yielded remarkable artifacts. Despite its significance, Tingambato remains underappreciated, drawing far fewer visitors than its more famous counterparts. This relative obscurity preserves its serene beauty and its hidden treasures, allowing explorers to wander through ancient pathways surrounded by verdant landscapes, evoking a sense of stepping back in time.

The site’s importance lies not only in its architectural remnants but also in what it tells researchers about human migration, trade networks, and societal evolution. After the collapse of Teotihuacan around AD 575, waves of people dispersed across Mesoamerica, carrying architectural styles and cultural practices to far-flung regions. Tingambato exemplifies this diaspora, with its talud-tablero, or slope-and-panel, features echoing those of the distant central Mexican powerhouse. Excavations have uncovered evidence of a sophisticated society engaged in agriculture, hunting, fishing, and long-distance commerce, as seen in exotic shells and lapidary objects from distant coasts.

In this episode of Mexico Unexplained, we will delve into the history, discovery, structures, artifacts, cultural significance, abandonment theories, modern conservation efforts, and visitor experiences at Tingambato. Through this exploration, we will uncover why this site is crucial for understanding the mosaic of ancient Mexican civilizations.

To appreciate Tingambato, one must situate it within the broader tapestry of Mesoamerican history. The Classic Period from AD 200 to AD 900, was a time of flourishing urban centers, intricate trade routes, and advanced artistic expressions across what is now Mexico and Central America. Teotihuacan, located in the Valley of Mexico, was the era’s dominant power, influencing regions as far as the Maya lowlands and the Pacific coast. Its eventual downfall—attributed to internal strife, environmental pressures, or invasions—triggered migrations that reshaped the cultural landscape. Tingambato’s occupation is divided into two main phases. The first, from around AD 450 to AD 600, marks the site’s initial development as a ceremonial and residential center. During this time, inhabitants constructed large platforms and pyramids using local materials, incorporating Teotihuacan-inspired elements like sloping walls (taluds) topped by vertical panels (tableros). This suggests early interactions with Teotihuacan, perhaps through trade or migration. The second phase, from AD 600 to AD 900, saw expansions including a prominent ball court, reinforcing ties to post-Teotihuacan sites like Tula and Xochicalco. This period aligns with the Epiclassic era, characterized by decentralization and the emergence of new polities. Tingambato’s inhabitants, likely proto-Tarascan or related groups, thrived in a fertile volcanic region ideal for agriculture. The local economy revolved around cultivating maize, beans, and squash, supplemented by hunting deer and gathering wild resources. Fishing in nearby lakes and rivers provided protein, while avocado orchards—still abundant today—hint at ancient horticultural practices. Archaeological evidence points to a stratified society with elites residing in multi-room complexes around sunken plazas. Religious rituals, including the Mesoamerican ball game, played a central role, symbolizing cosmic battles and fertility rites. Trade networks extended to the Pacific Ocean, as evidenced by marine shells, and possibly to central Mexico for obsidian tools and ceramics. By AD 900, Tingambato was abandoned, predating the consolidation of the Tarascan State around AD 1300. This gap intrigues scholars, suggesting environmental or social disruptions. Recent studies link the site’s demise to volcanic activity from nearby El Metate volcano, potentially causing fires and ashfall that forced evacuation.

To appreciate Tingambato, one must situate it within the broader tapestry of Mesoamerican history. The Classic Period from AD 200 to AD 900, was a time of flourishing urban centers, intricate trade routes, and advanced artistic expressions across what is now Mexico and Central America. Teotihuacan, located in the Valley of Mexico, was the era’s dominant power, influencing regions as far as the Maya lowlands and the Pacific coast. Its eventual downfall—attributed to internal strife, environmental pressures, or invasions—triggered migrations that reshaped the cultural landscape. Tingambato’s occupation is divided into two main phases. The first, from around AD 450 to AD 600, marks the site’s initial development as a ceremonial and residential center. During this time, inhabitants constructed large platforms and pyramids using local materials, incorporating Teotihuacan-inspired elements like sloping walls (taluds) topped by vertical panels (tableros). This suggests early interactions with Teotihuacan, perhaps through trade or migration. The second phase, from AD 600 to AD 900, saw expansions including a prominent ball court, reinforcing ties to post-Teotihuacan sites like Tula and Xochicalco. This period aligns with the Epiclassic era, characterized by decentralization and the emergence of new polities. Tingambato’s inhabitants, likely proto-Tarascan or related groups, thrived in a fertile volcanic region ideal for agriculture. The local economy revolved around cultivating maize, beans, and squash, supplemented by hunting deer and gathering wild resources. Fishing in nearby lakes and rivers provided protein, while avocado orchards—still abundant today—hint at ancient horticultural practices. Archaeological evidence points to a stratified society with elites residing in multi-room complexes around sunken plazas. Religious rituals, including the Mesoamerican ball game, played a central role, symbolizing cosmic battles and fertility rites. Trade networks extended to the Pacific Ocean, as evidenced by marine shells, and possibly to central Mexico for obsidian tools and ceramics. By AD 900, Tingambato was abandoned, predating the consolidation of the Tarascan State around AD 1300. This gap intrigues scholars, suggesting environmental or social disruptions. Recent studies link the site’s demise to volcanic activity from nearby El Metate volcano, potentially causing fires and ashfall that forced evacuation.

Tingambato’s modern rediscovery began in the mid-20th century, though local indigenous communities had long known of the ruins, integrating them into folklore. Historical references were scarce until systematic explorations in the 1970s. In the 1978–1979 field season, renowned Mexican archaeologist Román Piña Chan, in collaboration with Japanese researcher Kuniaki Ohi, led extensive excavations under the auspices of Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History, or INAH. Their work focused on the site’s ceremonial core, uncovering and restoring key structures. Piña Chan’s team revealed the ball court, pyramids, and residential areas, but only a fraction of the estimated 100-hectare settlement has been explored. Treasure hunters had looted parts earlier, yet the archaeologists made groundbreaking finds, including intact tombs overlooked by plunderers. In 1979, Tomb 1 was discovered beneath a platform, containing the remains of 104 to 150 individuals. This was a mass burial suggesting ritual sacrifice or epidemic victims. Accompanying offerings included ceramic vessels, shell figurines, musical instruments like ocarinas, and snails, indicating funerary rites tied to fertility and the underworld. A second major discovery came in 2011: Tomb 2, housing a single elite female aged 15–29 with intentional cranial deformation, a status marker in Mesoamerica. Buried with over 19,400 objects, including beads, pendants, and exotic shells from the Pacific and Gulf coasts, this tomb highlights Tingambato’s trade prowess and gives researchers a fascinating glimpse into gender roles in leadership. Subsequent investigations employed advanced technologies. In 2017, ground-penetrating radar surveys detected buried walls and graves, aiding in non-invasive mapping. Archaeomagnetic studies in 2023 dated pottery sherds exposed to fire, confirming a conflagration around AD 900. Drones, LiDAR, and high-resolution imaging enabled virtual reconstructions, visualizing the site at its AD 500 peak with colorful stucco facades and bustling plazas. These efforts have illuminated a lesser-known chapter of Michoacán’s prehistory, challenging narratives dominated by Aztec and Maya sites.

Tingambato’s modern rediscovery began in the mid-20th century, though local indigenous communities had long known of the ruins, integrating them into folklore. Historical references were scarce until systematic explorations in the 1970s. In the 1978–1979 field season, renowned Mexican archaeologist Román Piña Chan, in collaboration with Japanese researcher Kuniaki Ohi, led extensive excavations under the auspices of Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History, or INAH. Their work focused on the site’s ceremonial core, uncovering and restoring key structures. Piña Chan’s team revealed the ball court, pyramids, and residential areas, but only a fraction of the estimated 100-hectare settlement has been explored. Treasure hunters had looted parts earlier, yet the archaeologists made groundbreaking finds, including intact tombs overlooked by plunderers. In 1979, Tomb 1 was discovered beneath a platform, containing the remains of 104 to 150 individuals. This was a mass burial suggesting ritual sacrifice or epidemic victims. Accompanying offerings included ceramic vessels, shell figurines, musical instruments like ocarinas, and snails, indicating funerary rites tied to fertility and the underworld. A second major discovery came in 2011: Tomb 2, housing a single elite female aged 15–29 with intentional cranial deformation, a status marker in Mesoamerica. Buried with over 19,400 objects, including beads, pendants, and exotic shells from the Pacific and Gulf coasts, this tomb highlights Tingambato’s trade prowess and gives researchers a fascinating glimpse into gender roles in leadership. Subsequent investigations employed advanced technologies. In 2017, ground-penetrating radar surveys detected buried walls and graves, aiding in non-invasive mapping. Archaeomagnetic studies in 2023 dated pottery sherds exposed to fire, confirming a conflagration around AD 900. Drones, LiDAR, and high-resolution imaging enabled virtual reconstructions, visualizing the site at its AD 500 peak with colorful stucco facades and bustling plazas. These efforts have illuminated a lesser-known chapter of Michoacán’s prehistory, challenging narratives dominated by Aztec and Maya sites.

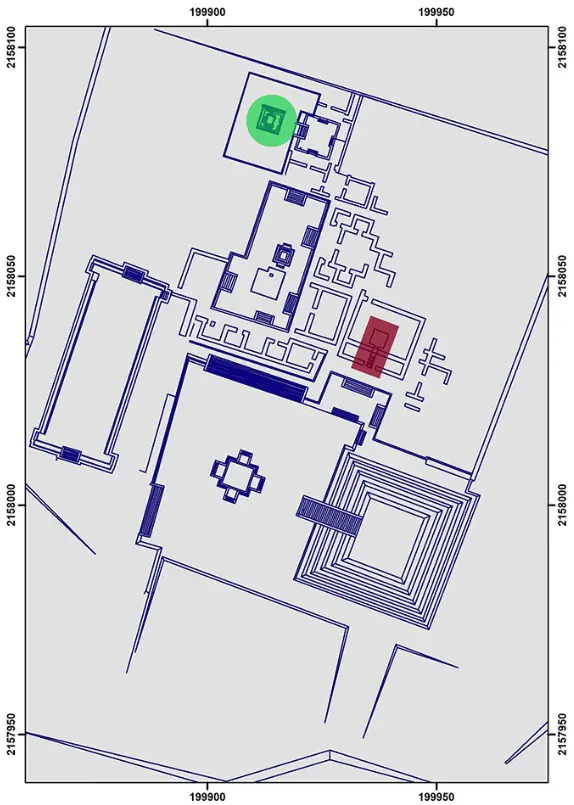

Tingambato’s layout reflects a planned urban design, with structures aligned to cardinal directions and astronomical events. The site occupies a terraced hillside, leveraging natural topography for defense and symbolism. Two main mounds dominate: the Eastern Structure, a stepped pyramid with talud-tablero facades, and the larger Western Structure, yet to be fully excavated. At the center lies the ball court, a 40-meter-long I-shaped arena sunk into a platform, reminiscent of those at Monte Albán in Oaxaca. Flanked by sloping walls, it hosted the ritual ball game, where players used hips to propel a rubber ball, symbolizing solar cycles and warfare. Unlike Maya courts with rings, Tingambato’s emphasizes open play, aligning with Teotihuacan traditions. For more information about the Mesoamerican ball game, please see Mexico Unexplained episode number 53 https://youtu.be/DsHZFf6_bmo Surrounding the court are sunken patios with altars. Altar 3, quadrangular with dual stairways, features slope-and-board construction, possibly for offerings or ceremonies. Adjacent rooms, arranged around plazas, suggest elite residences or temples, with hearths and storage pits indicating daily life. Platforms and terraces, built in phases, demonstrate engineering prowess. Early constructions used rubble cores with stone facings, later enhanced with stucco. Teotihuacan influence is evident in the talud-tablero style, where sloping bases prevent erosion while symbolizing mountains and pyramids. The site’s integration with nature—amid groves and overlooking valleys— gives it a spiritual aura. Water channels and drainage systems hint at hydraulic knowledge, vital in a volcanic region prone to rains.

Excavations have yielded a wealth of artifacts, painting a vivid picture of daily and ritual life. Ceramics dominate, with polychrome pots featuring geometric motifs and anthropomorphic figures, influenced by Teotihuacan styles but adapted locally. Vessels from Tomb 1 include utilitarian wares for food and incense burners for rituals. Shell artifacts stand out, with over 19,000 in Tomb 2 alone. Sourced from distant seas, they include conch trumpets, pendants, and beads, signifying status and trade. Snails and marine fauna suggest symbolic ties to water deities and fertility. Figurines depict humans with elaborate headdresses, possibly priests or deities, while musical instruments like shell ocarinas and whistles indicate ceremonial music. Obsidian tools, imported from central Mexico, show craftsmanship in blades and arrowheads. Bioarchaeological analysis reveals health insights: dental mutilation in Tomb 1 skeletons (filing or inlays) denoted elite status, while cranial deformation in Tomb 2’s occupant highlights beauty standards. Pathologies suggest a diet rich in maize but susceptible to nutritional deficiencies. These finds underscore Tingambato’s role in regional networks, exchanging avocados and metals for exotic goods.

Excavations have yielded a wealth of artifacts, painting a vivid picture of daily and ritual life. Ceramics dominate, with polychrome pots featuring geometric motifs and anthropomorphic figures, influenced by Teotihuacan styles but adapted locally. Vessels from Tomb 1 include utilitarian wares for food and incense burners for rituals. Shell artifacts stand out, with over 19,000 in Tomb 2 alone. Sourced from distant seas, they include conch trumpets, pendants, and beads, signifying status and trade. Snails and marine fauna suggest symbolic ties to water deities and fertility. Figurines depict humans with elaborate headdresses, possibly priests or deities, while musical instruments like shell ocarinas and whistles indicate ceremonial music. Obsidian tools, imported from central Mexico, show craftsmanship in blades and arrowheads. Bioarchaeological analysis reveals health insights: dental mutilation in Tomb 1 skeletons (filing or inlays) denoted elite status, while cranial deformation in Tomb 2’s occupant highlights beauty standards. Pathologies suggest a diet rich in maize but susceptible to nutritional deficiencies. These finds underscore Tingambato’s role in regional networks, exchanging avocados and metals for exotic goods.

Tingambato was a ceremonial hub, where religion intertwined with politics and economy. The ball game, central to Mesoamerican cosmology, reenacted creation myths, with losers potentially sacrificed. Altars likely hosted bloodletting or offerings to gods of rain and agriculture. Teotihuacan influence implies adopted deities like the Storm God or Feathered Serpent, blended with local Tarascan precursors. Tombs reflect beliefs in the afterlife, with mass burials possibly commemorating events like volcanic eruptions. The site’s abandonment around AD 900, marked by fire, may tie to rituals or catastrophes. Archaeomagnetic data from burned sherds supports theories of deliberate burning or natural disasters, linking to El Metate’s eruptions. Tingambato bridges cultural phases, showing how migrations fostered hybrid identities, paving the way for the Tarascan empire’s metallurgy and statecraft.

The site’s sudden desertion puzzles experts. Evidence of widespread fire, including charred beams and burned pottery, suggests violence, migration, or environmental calamity. A 2023 study proposes volcanic activity from El Metate, with ash layers indicating eruptions that scorched the landscape. Climate shifts, droughts, or over farming may have contributed, echoing theories of Teotihuacan’s fall. No evidence of invasion exists, but internal conflicts can’t be ruled out. Contemporary research uses non-destructive methods: GPR identifies anomalies, while virtual models reconstruct vibrant scenes. These tools aid preservation amid threats like urban sprawl and looting.

The site’s sudden desertion puzzles experts. Evidence of widespread fire, including charred beams and burned pottery, suggests violence, migration, or environmental calamity. A 2023 study proposes volcanic activity from El Metate, with ash layers indicating eruptions that scorched the landscape. Climate shifts, droughts, or over farming may have contributed, echoing theories of Teotihuacan’s fall. No evidence of invasion exists, but internal conflicts can’t be ruled out. Contemporary research uses non-destructive methods: GPR identifies anomalies, while virtual models reconstruct vibrant scenes. These tools aid preservation amid threats like urban sprawl and looting.

INAH oversees Tingambato, maintaining paths and signage. A small on-site museum displays excavation photos and replicas, educating visitors. Conservation focuses on erosion control and vegetation management, preserving the avocado-framed serenity. Tourism is low-key: entry is affordable – around 50 pesos – with guided tours available. Access via bus from Uruapan or car takes about 30 minutes. Visitors praise the site’s tranquility, contrasting crowded ruins in other parts of Mexico. Efforts at the site promote sustainable tourism, involving locals in guides and crafts, boosting the local economy while protecting ancient heritage. Challenges include funding shortages, but international collaborations enhance studies and research.

Tingambato encapsulates the enigma of ancient Mexico: a site of innovation, exchange, and mystery. From Teotihuacan echoes to precursors of the Tarascan Empire, it reveals migrations shaping civilizations. Its tombs whisper of elites and rituals, while structures stand as enduring monuments. As research advances, Tingambato’s story unfolds, reminding us of humanity’s resilience amid change. Whether scholar or traveler, visiting evokes wonder at this “place where the fire ends,” or perhaps begins anew in our understanding. In a world of forgotten histories, Tingambato shines as a beacon of the past, inviting exploration and reflection.

REFERENCES

Pérez-Rodríguez, Nayeli, Josué Morales, Marie-Noëlle Guilbaud, Avto Goguitchaichvili, Francisco R. Cejudo-Ruiz, and María del Sol Hernández-Bernal. “Human Migrations and Volcanic Activity: Archaeomagnetic Evidence of the Probable Abandonment of the Tingambato Archaeological Site Due to the Eruption of El Metate Volcano (Mexico).” Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences 15, no. 11 (2023): 174