Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

The date was June 7, 1494 and the place was the town of Tordesillas on the banks of the Douro River in central Spain. Pope Alexander the Sixth had drafted a treaty to help clarify the confusion over ownership of newly discovered lands beyond Europe. Attending the signing of the treaty were three sovereigns and a crown prince: King John the Second of Portugal, King Ferdinand the Second of Aragon, Queen Isabella the First of Castille and the son of Ferdinand and Isabella, John, Prince of Asturias. The treaty essentially divided up the world between Portugal and the united Castille and Aragon – Spain – along an imaginary line 100 leagues west of the Azores. Spain got exclusive ownership rights to lands west of the meridian and Portugal retained ownership to all the lands to the east. As a result of the Treaty of Tordesillas, Portugal got Africa, Asia and part of Brazil, and Spain got the rest of the Americas and all the lands bordering the Pacific Ocean to the exclusion of all other European powers. Over the years, even after their respective presences were established in their allotted hemispheres, other European countries who were not part of the treaty challenged Portugal and Spain by setting up colonies and trading outposts of their own in supposed Portuguese and Spanish territories. Many skirmishes and conflicts over land occurred, especially as other European nations became more powerful and wished to expand their empires as Spain and Portugal had done. Many people do not know of the territorial disputes that existed in the Pacific Northwest between the British, the Russians, the Spanish and the Americans in the latter part of the 1700s or the strange colonial history of the area known today as Alaska. Sold to the United States by Imperial Russia in 1867 for 7.2 million dollars, some questions arise when looking closely at the true ownership of Alaska. Did the Russians have a right to sell territory that legitimately might not have been theirs to sell? What country was the rightful owner of Alaska at the time of the American occupation? With vague treaties to sort out the overlapping Pacific Northwest claims throughout the years, a case could be made today that the rightful owner of Alaska is modern-day country of Mexico.

The date was June 7, 1494 and the place was the town of Tordesillas on the banks of the Douro River in central Spain. Pope Alexander the Sixth had drafted a treaty to help clarify the confusion over ownership of newly discovered lands beyond Europe. Attending the signing of the treaty were three sovereigns and a crown prince: King John the Second of Portugal, King Ferdinand the Second of Aragon, Queen Isabella the First of Castille and the son of Ferdinand and Isabella, John, Prince of Asturias. The treaty essentially divided up the world between Portugal and the united Castille and Aragon – Spain – along an imaginary line 100 leagues west of the Azores. Spain got exclusive ownership rights to lands west of the meridian and Portugal retained ownership to all the lands to the east. As a result of the Treaty of Tordesillas, Portugal got Africa, Asia and part of Brazil, and Spain got the rest of the Americas and all the lands bordering the Pacific Ocean to the exclusion of all other European powers. Over the years, even after their respective presences were established in their allotted hemispheres, other European countries who were not part of the treaty challenged Portugal and Spain by setting up colonies and trading outposts of their own in supposed Portuguese and Spanish territories. Many skirmishes and conflicts over land occurred, especially as other European nations became more powerful and wished to expand their empires as Spain and Portugal had done. Many people do not know of the territorial disputes that existed in the Pacific Northwest between the British, the Russians, the Spanish and the Americans in the latter part of the 1700s or the strange colonial history of the area known today as Alaska. Sold to the United States by Imperial Russia in 1867 for 7.2 million dollars, some questions arise when looking closely at the true ownership of Alaska. Did the Russians have a right to sell territory that legitimately might not have been theirs to sell? What country was the rightful owner of Alaska at the time of the American occupation? With vague treaties to sort out the overlapping Pacific Northwest claims throughout the years, a case could be made today that the rightful owner of Alaska is modern-day country of Mexico.

After the Spanish Conquest of the Aztecs in the early 1520s, Spain established the Viceroyalty of New Spain and solidified its control over most of what is now Mexico. Although explorers proposed expeditions up the coast of western North America to look for the Northwest Passage or the fabled Strait of Anián, no voyages of exploration got approval from the Spanish authorities until well into the 1700s. At this time news arrived in Mexico City that the Russians were staking claims to parts of northwest Pacific coast and that the British were increasing their trading activity in the region. Spanish authorities thought their claims to the entirety of northwestern North America were beyond dispute, as New Spain technically did not have a northern boundary. Spain had a problem, however; without a permanent presence in the area, their claim was shaky at best, with only the assumption that the Spanish owned all the land up to and through Alaska and the seemingly defunct Treaty of Tordesillas giving them the right to the land some three centuries before.

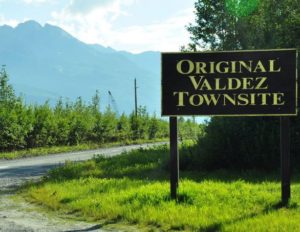

By the early 1770s the King of Spain instructed the Viceroy of New Spain, Antonio María Bucareli, to start sending expeditions to the Pacific Northwest to map the area and open it up for colonization. The king also wanted intelligence on possible Russian and British activity in the area. The colonial authorities made improvements to the Pacific port of San Blas, located in the modern Mexican state of Nayarit, to serve as the base for all northwestern explorations. In 1774, Viceroy Bucareli sent Juan José Pérez Hernández to explore the northern Pacific coast with the objective of reaching as far north as 60° north latitude, near the present-day town of Cordova, Alaska. Pérez’ ship, the frigate Santiago, made it as far north as 54° north latitude past the Queen Charlotte Islands now known as the Haida Gwaii. Pérez became the first European to sight the coast of British Columbia and first to explore the islands off its coast. He had to turn the ship back to San Blas because of an ill crew and because the ship had run low on provisions. The Santiago would return to the north again the following year. The second Pacific Northwest expedition left San Blas on March 16, 1775 with two other ships the Sonora and the San Carlos. All three ships made it to Monterey Bay in Spanish-controlled Alta California and went north to the area of the modern-day state of Washington. Again because of crew illness, the Santiago turned back but the other two ships pressed onward, eventually making it to Sitka Sound, the site of modern-day Sitka, Alaska, before returning to San Blas. Along the way the crews of the ships mapped the coasts and islands and performed acts of sovereignty including planting wooden crosses on shore proclaiming the newly discovered lands as belonging to “His Most Catholic Majesty,” the king of Spain. During this second voyage of exploration the ships had no encounters with the Russians or the British. This would soon change. The Spanish authorities in Mexico City were confidently and leisurely planning a third voyage when they heard the news of the arrival of one of Great Britain’s greatest explorers in the area that they had just reestablished their claim over. Captain James Cook of the British Navy was exploring the coasts of Alaska and British Columbia. The Cook expedition was one of mapping and discovery and not one to claim new territory for Britain. The year was 1778.

By the early 1770s the King of Spain instructed the Viceroy of New Spain, Antonio María Bucareli, to start sending expeditions to the Pacific Northwest to map the area and open it up for colonization. The king also wanted intelligence on possible Russian and British activity in the area. The colonial authorities made improvements to the Pacific port of San Blas, located in the modern Mexican state of Nayarit, to serve as the base for all northwestern explorations. In 1774, Viceroy Bucareli sent Juan José Pérez Hernández to explore the northern Pacific coast with the objective of reaching as far north as 60° north latitude, near the present-day town of Cordova, Alaska. Pérez’ ship, the frigate Santiago, made it as far north as 54° north latitude past the Queen Charlotte Islands now known as the Haida Gwaii. Pérez became the first European to sight the coast of British Columbia and first to explore the islands off its coast. He had to turn the ship back to San Blas because of an ill crew and because the ship had run low on provisions. The Santiago would return to the north again the following year. The second Pacific Northwest expedition left San Blas on March 16, 1775 with two other ships the Sonora and the San Carlos. All three ships made it to Monterey Bay in Spanish-controlled Alta California and went north to the area of the modern-day state of Washington. Again because of crew illness, the Santiago turned back but the other two ships pressed onward, eventually making it to Sitka Sound, the site of modern-day Sitka, Alaska, before returning to San Blas. Along the way the crews of the ships mapped the coasts and islands and performed acts of sovereignty including planting wooden crosses on shore proclaiming the newly discovered lands as belonging to “His Most Catholic Majesty,” the king of Spain. During this second voyage of exploration the ships had no encounters with the Russians or the British. This would soon change. The Spanish authorities in Mexico City were confidently and leisurely planning a third voyage when they heard the news of the arrival of one of Great Britain’s greatest explorers in the area that they had just reestablished their claim over. Captain James Cook of the British Navy was exploring the coasts of Alaska and British Columbia. The Cook expedition was one of mapping and discovery and not one to claim new territory for Britain. The year was 1778.

The third Spanish expedition to the Pacific Northwest, which set sail from San Blas in 1779 had three objectives: To look for the Northwest Passage, to assess the extent of Russian involvement in Alaska and to capture Captain Cook. Unknown to the Spanish, Cook had been killed in Hawaii earlier in the year. On August 2, 1779 this third expedition made it as far north as the Kenai Peninsula and modern-day Anchorage, Alaska, and claimed all the land it surveyed for Spain. During this third expedition Spain had entered the American Revolutionary War as an ally of France and thus made it an enemy of Britain. After the third expedition returned to San Blas there were no more expeditions northward because of the war. Spain decided to put its resources and attention elsewhere. In the meantime, though, the Russians began making inroads into formally claimed Spanish territory in Alaska. News of increasing Russian influence on Spain’s northern flanks slowly trickled down to Mexico City.

The third Spanish expedition to the Pacific Northwest, which set sail from San Blas in 1779 had three objectives: To look for the Northwest Passage, to assess the extent of Russian involvement in Alaska and to capture Captain Cook. Unknown to the Spanish, Cook had been killed in Hawaii earlier in the year. On August 2, 1779 this third expedition made it as far north as the Kenai Peninsula and modern-day Anchorage, Alaska, and claimed all the land it surveyed for Spain. During this third expedition Spain had entered the American Revolutionary War as an ally of France and thus made it an enemy of Britain. After the third expedition returned to San Blas there were no more expeditions northward because of the war. Spain decided to put its resources and attention elsewhere. In the meantime, though, the Russians began making inroads into formally claimed Spanish territory in Alaska. News of increasing Russian influence on Spain’s northern flanks slowly trickled down to Mexico City.

By 1788 the stories of Russian expansion could not be ignored. Spain sent two ships north, the Princesa and the San Carlos, captained by Esteban José Martínez and Gonzalo López de Haro, respectively. They made it to Kodiak Island by May of 1788 and heard from the local indigenous people that a Russian outpost was nearby. The Spanish sailed into Three Saints Bay and found a Russian fur trading station commanded by a man named Evstrat Delarov. Delarov told Captain López de Haro that the Russians had seven permanent trading posts in Alaska containing over 500 men, and that they planned on trading farther along the cost, with intent to establish colonies as far south as Vancouver Island. The two Spanish ships sailed on to Unalaska in the Aleutian Islands where they came upon a large Russian outpost commanded by a man named Potap Zaikov. Zaikov told the Spanish that the Russians already had two frigates headed for Nootka Island, a small piece of land off the western shore of Vancouver Island, with the objective of setting up a permanent Russian colony there. The two Spanish ships had briefly stopped at Nootka Sound on their way up north and had discovered a British trading ship in its waters. Apparently, the British were also interested in the western shores of Vancouver Island. When the third expedition returned to San Blas at the end of 1788, the Viceroy of New Spain had new plans: he wanted a permanent Spanish presence in the Pacific Northwest and decided to start with Nootka Island.

In charge of the colonization force, Esteban José Martínez arrived at Nootka on May 5, 1789. Ten days later he selected an area for the permanent settlement on what is now known as Hog Island. Within a month the Spanish had built houses, barracks, military fortifications, a hospital and even started raising vegetables. They christened the fort San Miguel and named the colony as a whole Santa Cruz de Nuca. On old Spanish maps, the big swath of territory including parts of modern-day British Columbia, Yukon Territory and Alaska is labeled “Territorio de Nuca.” Within months, the thriving colony soon met face to face with British and American fur trading vessels. A British merchant named John Meares even claimed to have bought land on Nootka Sound from a local Indian chief the year before. Two British ships associated with Meares’ operation, the Princess Royal and the Argonaut were seized by Captain Martínez. The two ships had sailed from China and were at Nootka to build a small fur trapping station to process furs to export to the Orient. The Spanish confiscated the ship’s supplies and took command over the Chinese laborers brought to Nootka to build the fur processing facility. Martínez used the Chinese laborers to build out the Spanish colony and increase the land under cultivation. Little did he know, but his actions were creating an international incident. A footnote in most history books, what happened next was called the Nootka Crisis which would result in the three Nootka Conventions to sort everything out. By the end of July 1789, the Viceroy in Mexico City ordered the colony of Santa Cruz de Nuca to be abandoned. The Spanish packed up everything and returned to San Blas.

The main negotiators during the Nootka Conventions were George Vancouver for the British and Juan Francisco de la Bodega y Quadra for the Spanish. The first Nootka Convention signed October 28, 1790 mandated the return of buildings and tracts of land seized by the Spanish from the British in the previous year. When Vancouver and Quadra went to Nootka to investigate this, they found that the British had no buildings or property seized by the Spanish; only the private property of the merchant John Meares had been confiscated. So, the Second Nootka Convention of February 1793 addressed Meares’ claims and awarded him compensation for the Spanish seizure of his ships and other property. The Third Nootka Convention also called the Convention for the Mutual Abandonment of Nootka was signed on January 11, 1794 and served as a joint use agreement for Spain and Britain. The two powers could use Nootka Sound as they each saw fit so long as either party did not establish permanent colonies there. The convention did not define territory and the northern limits of New Spain remained unresolved. The Nootka Conventions did not address any activity north of the Vancouver Island area. Alaska was not even mentioned once.

The main negotiators during the Nootka Conventions were George Vancouver for the British and Juan Francisco de la Bodega y Quadra for the Spanish. The first Nootka Convention signed October 28, 1790 mandated the return of buildings and tracts of land seized by the Spanish from the British in the previous year. When Vancouver and Quadra went to Nootka to investigate this, they found that the British had no buildings or property seized by the Spanish; only the private property of the merchant John Meares had been confiscated. So, the Second Nootka Convention of February 1793 addressed Meares’ claims and awarded him compensation for the Spanish seizure of his ships and other property. The Third Nootka Convention also called the Convention for the Mutual Abandonment of Nootka was signed on January 11, 1794 and served as a joint use agreement for Spain and Britain. The two powers could use Nootka Sound as they each saw fit so long as either party did not establish permanent colonies there. The convention did not define territory and the northern limits of New Spain remained unresolved. The Nootka Conventions did not address any activity north of the Vancouver Island area. Alaska was not even mentioned once.

So, what of the Spanish claims on Alaska? They still existed after the Nootka Conventions despite ever-increasing Russian influence in the area. The Russian-America Company expanded its efforts in Alaska in the 1790s and by 1804 it established on Baranof Island what would become the capital of Russian America called New Archangel, the site of Sitka today. Involved in wars on the European continent and unrest in its American colonies, Spain paid little attention to Russian activity on the northern fringes of its American empire at this time.

By the early 1800s with the Louisiana Purchase and the Lewis and Clark Expedition, Americans were pouring into the Pacific Northwest into what had been termed by Britain and the US as Oregon Country. Oregon Country included those lands west of the Louisiana purchase roughly including the modern US states of Washington, Oregon and parts of Idaho, and the southern part of the modern Canadian province of British Columbia. While technically part of New Spain, the Oregon Country saw sparse visits from Spaniards and had no permanent Spanish settlements. Spain divorced itself from the Oregon Country in 1819 with the Adams-Onis Treaty. The treaty, signed between the United States and Spain, ceded Spanish Florida to the US in exchange for $5 million to be paid to US citizens who had claims against Spain. The treaty also defined the border between New Spain and the United States as well as setting the border between New Spain and the Oregon Country, which had been traversed and exploited by the British, Russians and Americans but whose ownership status was undetermined. The Adams-Onis Treaty once again did not address Alaska. It gave Florida to the US and also defined the United States’ border with New Spain.

By the early 1800s with the Louisiana Purchase and the Lewis and Clark Expedition, Americans were pouring into the Pacific Northwest into what had been termed by Britain and the US as Oregon Country. Oregon Country included those lands west of the Louisiana purchase roughly including the modern US states of Washington, Oregon and parts of Idaho, and the southern part of the modern Canadian province of British Columbia. While technically part of New Spain, the Oregon Country saw sparse visits from Spaniards and had no permanent Spanish settlements. Spain divorced itself from the Oregon Country in 1819 with the Adams-Onis Treaty. The treaty, signed between the United States and Spain, ceded Spanish Florida to the US in exchange for $5 million to be paid to US citizens who had claims against Spain. The treaty also defined the border between New Spain and the United States as well as setting the border between New Spain and the Oregon Country, which had been traversed and exploited by the British, Russians and Americans but whose ownership status was undetermined. The Adams-Onis Treaty once again did not address Alaska. It gave Florida to the US and also defined the United States’ border with New Spain.

Two years after Adams-Onis, Spain gave Mexico its independence. In the treaty recognizing New Spain as the independent nation of Mexico, the Spanish Crown declared that former territories of New Spain would be Mexican. While the treaty did not specifically mention Alaska, those areas north of the Oregon Country were still technically part of New Spain, including parts of modern-day British Columbia, the Yukon Territory and the present US state of Alaska. As mentioned earlier, the Russians sold Alaska to the Americans in 1867, but the question remains, did they have the legal right to do so, or does Alaska really belong to Mexico?

REFERENCES

Olson, Wallace M. Through Spanish Eyes: Spanish Voyages to Alaska, 1774-1792. Auke Bay, Alaska: Heritage Research Press, 2002.

Thurman, Michael E. The Naval Department of San Blas, New Spain’s Bastion of Alta California and Nootka 1767 to 1798. Glendale, California: The Arthur H. Clark Company, 1967.

2 thoughts on “Does Alaska Belong to Mexico?”

For some reason the podcast keeps playing the intro music and then the announcer speaks & is cut off….then the music plays again!! Check it out.

Hi Cassie, Thanks for telling me this. It must have been a momentary glitch. I went to play it and it worked just fine for me. I am glad you brought this to my attention because a few months ago another viewer/listener reported something similar on another show. Try refreshing your browser and try again, or unplug your computer! (just kidding, don’t do that) 🙂