Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

The year was 1519. In the imperial palace at Tenochtitlán a little girl overheard what the messengers were telling some of the senior members of the Aztec royal family. Large houses had arrived floating on the ocean and inside them there were men who were made partly of metal, and they rode gigantic deer. These strange men also carried with them long pieces of metal that made loud and frightful noises. These newcomers spoke an unusual language. The little girl, only nine years old, stood beside her mother and was too young to process it all. Her name was Tecuichpoch Ichcaxochitzin. Her father was the reigning emperor of the Mexica and all the subjected realms, a man known to history as Montezuma the Second. The little girl’s mother was the Princess Teotlalco, wife of Montezuma and daughter of King Matlaccohuatl, the ruler of the wealthy Kingdom of Ecatepec. The little girl, Princess Tecuichpoch Ichcaxochitzin, would have a brief but interesting life and as the last Aztec Empress she would serve as a bridge between an old order and something new that the world had not yet seen. For most of her life, she would be known as Doña Isabel Moctezuma.

The year was 1519. In the imperial palace at Tenochtitlán a little girl overheard what the messengers were telling some of the senior members of the Aztec royal family. Large houses had arrived floating on the ocean and inside them there were men who were made partly of metal, and they rode gigantic deer. These strange men also carried with them long pieces of metal that made loud and frightful noises. These newcomers spoke an unusual language. The little girl, only nine years old, stood beside her mother and was too young to process it all. Her name was Tecuichpoch Ichcaxochitzin. Her father was the reigning emperor of the Mexica and all the subjected realms, a man known to history as Montezuma the Second. The little girl’s mother was the Princess Teotlalco, wife of Montezuma and daughter of King Matlaccohuatl, the ruler of the wealthy Kingdom of Ecatepec. The little girl, Princess Tecuichpoch Ichcaxochitzin, would have a brief but interesting life and as the last Aztec Empress she would serve as a bridge between an old order and something new that the world had not yet seen. For most of her life, she would be known as Doña Isabel Moctezuma.

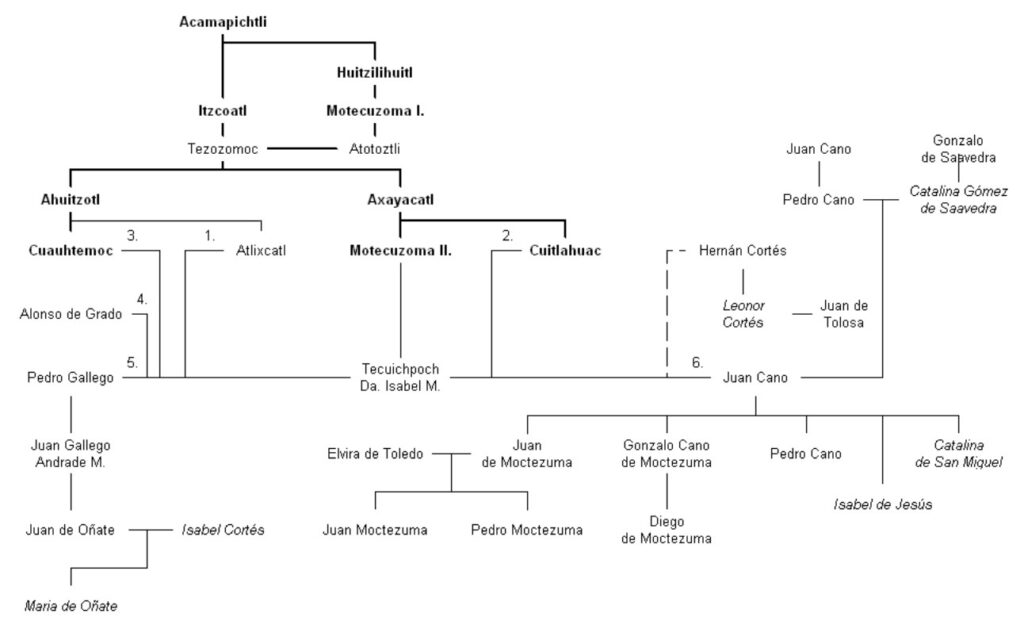

As a small child, Doña Isabel was married to Atlixcatzin who was a high-ranking general in the Aztec army and a close advisor to Emperor Montezuma the Second. Atlixcatzin died during the initial Aztec revolt against the Spanish on June 30, 1520 now known as La Noche Triste, thus leaving the princess a widow at the age of 10. In the turmoil that followed, Doña Isabel’s father, Emperor Montezuma the Second, was killed and her uncle Cuitláhuac became ruler of the Aztecs. The Aztec leadership thought it best for Doña Isabel to marry Emperor Cuitláhuac even though the capital city was under siege, and many were dying of starvation or smallpox. Cuitláhuac succumbed to the pox 80 days after he was installed as emperor and the young Doña Isabel became a widow once again. After her second husband’s death, she was married off again, this time to the newly crowned Emperor Cuauhtémoc who was the eldest son of perhaps the greatest Aztec emperor who ever lived – Ahuízotl – talked about in Mexico Unexplained Episode number 344 https://mexicounexplained.com/emperor-ahuizotl-and-the-expansion-of-the-aztec-empire/ Cuauhtémoc was around 25 years old at the time and Doña Isabel was either 10 or 11. By the time Cuauhtémoc assumed power, the Aztec Empire was nearly finished. The emperor’s calls for reinforcements from the countryside to help defend Tenochtitlán went mostly unheeded as previous allies joined the side of the Spanish. On August 13, 1521, Cuauhtémoc with Doña Isabel by his side, along with other high-ranking members of the Aztec nobility, tried to make an escape from the besieged capital city on a large boat across Lake Texcoco. The boat was apprehended by Cortés and his men, and according to  some reports, the Aztec emperor asked Cortés to strike him down with a blade, as long as he saved the women in his family. The conquistador acted magnanimously and spared the life of the emperor and all the lives of those in the escaping boat, including that of Doña Isabel. According to William Prescott in his book, History of the Conquest of Mexico, Cortés declared: “You have defended your capital like a brave warrior. A Spaniard knows how to respect valor, even in an enemy.” Cortés knew that he needed to work with Mexico’s indigenous nobility to further Spain’s ambitions in the New World. Although removed from power, the native rulers were allowed to keep their titles and were afforded other privileges that continue even well into the 21st Century. Partially because he was uneasy leaving him behind in Tenochtitlán, Cortés took the former emperor Cuauhtémoc on an expedition with him to what is now Honduras in Central America. During that trip Cortés suspected that the last tlatoani of the Aztecs was plotting against him and had him executed, thus making Doña Isabel a widow once again, at the age of 15.

some reports, the Aztec emperor asked Cortés to strike him down with a blade, as long as he saved the women in his family. The conquistador acted magnanimously and spared the life of the emperor and all the lives of those in the escaping boat, including that of Doña Isabel. According to William Prescott in his book, History of the Conquest of Mexico, Cortés declared: “You have defended your capital like a brave warrior. A Spaniard knows how to respect valor, even in an enemy.” Cortés knew that he needed to work with Mexico’s indigenous nobility to further Spain’s ambitions in the New World. Although removed from power, the native rulers were allowed to keep their titles and were afforded other privileges that continue even well into the 21st Century. Partially because he was uneasy leaving him behind in Tenochtitlán, Cortés took the former emperor Cuauhtémoc on an expedition with him to what is now Honduras in Central America. During that trip Cortés suspected that the last tlatoani of the Aztecs was plotting against him and had him executed, thus making Doña Isabel a widow once again, at the age of 15.

While Cortés and Cuauhtémoc were in Central America, the princess formerly known as Tecuichpoch Ichcaxochitzin converted to Christianity and was baptized with the name Doña Isabel Moctezuma. By all accounts, she embraced her new faith wholeheartedly and was educated by the Augustinians but never learned to read or write. She was known to make large donations to church projects. It is unknown whether she did all of this as a political strategy to ensure the survival of herself and her family, or if she internalized the new faith and became a true believer. Cortés ensured that the princess was well taken care of and educated in Spanish ways because he wanted Doña Isabel to serve as a symbol of continuity between the Aztec and Spanish rule over the former Aztec Empire. Within a year of the last emperor’s death, Doña Isabel married her 4th husband, Spanish army captain Alonso de Grado a man who was at the side of Cortés from the early days in Cuba all the way through the expedition to Central America. The marriage was arranged by Cortés and as a result Doña Isabel was given an encomienda at Tacuba, one of the largest in all Mexico. Briefly, an encomienda is the right to indigenous labor in a designated geographical area. The subjects of the encomienda are vassals of the encomendero, or in this case, the encomendera, who is the one granted the encomienda. In exchange, theoretically, the encomendero is responsible for keeping his charges safe, educated and healthy. It was a softer type of slavery than Doña Isabel was used to as a member of the ruling family of the Aztec Empire. By giving her such a large encomienda, he was further legitimizing and perpetuating the nobility of the old  Aztec system and was gently folding it into the new Spanish imperial system. As an important aside, it is somewhat inconceivable for people in the 21st Century to accept that in the eyes of the Spaniards of 500 years ago, Christianized members of native nobility were equal to Spanish nobility. Cortés granted Doña Isabel’s husband the title of Visitador Real and with that title came the responsibility of overseeing the Christianization and the overall well-being of the native populations of New Spain. He was part auditor and part investigator in the name of the Spanish king. Don Alonso died on one of his assignments and Doña Isabel found herself a widow for the fourth time right before she turned 17.

Aztec system and was gently folding it into the new Spanish imperial system. As an important aside, it is somewhat inconceivable for people in the 21st Century to accept that in the eyes of the Spaniards of 500 years ago, Christianized members of native nobility were equal to Spanish nobility. Cortés granted Doña Isabel’s husband the title of Visitador Real and with that title came the responsibility of overseeing the Christianization and the overall well-being of the native populations of New Spain. He was part auditor and part investigator in the name of the Spanish king. Don Alonso died on one of his assignments and Doña Isabel found herself a widow for the fourth time right before she turned 17.

After the death of her fourth husband, Cortés himself took in Doña Isabel and she lived in close proximity to him on one of his estates. Soon she became pregnant with Cortés’ child, and because the conquistador already had a wife, he married Doña Isabel off again to a Spaniard named Pedro Gallego de Andrade. When Cortés’ child was born, a girl, they named her Leonor Cortés Montezuma and Doña Isabel refused to recognize her as legitimate. Cortés, however, accepted Leonor as his own and ensured that she had a good life and that she would be well provided for through inheritances on both sides of her family. In 1530, Doña Isabel had a son with her 5th husband, a boy they named Juan de Andrade Gallego Moctezuma. Soon after the boy’s birth, Doña Isabel’s husband died, leaving her a widow for the fifth time.

In 1532 she married her sixth husband, Juan Cano de Saavedra, a conquistador from Extremadura who participated in the Pánfilo de Narváez Expedition and who also fought alongside Cortés. With Cano de Saavedra she had three sons and two daughters: Pedro, Gonzalo, Juan, Isabel, and Catalina Cano de Moctezuma. In the early 1550s, the two Cano de Moctezuma girls became nuns in the first convent in Mexico, the Convento de la Concepción de la Madre de Dios which still stands today in the historic heart of Mexico City.

Doña Isabel would not become a widow for the sixth time. She died in either 1550 or 1551 and her husband would live for more than 20 more years. Some historians consider her legacy to be more important than her life. As the legitimate inheritor of the Aztec royal family’s wealth, and as the last Aztec Empress, Doña Isabel left behind a sizable estate. This included land in various parts of New Spain, the gigantic encomienda at Tacuba, many slaves that she was allowed to keep under the Aztec nobility’s agreement with Cortés and untold amounts of gold and jewels. During her brief life, most of it under the protection of the Spanish Crown, Doña Isabel accumulated more wealth than what had been passed down to her through her noble inheritance. At the time of her death her estate was so vast and complex that it spent many years in litigation with various claimants contesting parts of her will. Doña Isabel’s long will is considered thoughtful and concise by historians and gives great insight into the character of this woman who seems to have made a seamless transition in her life from indigenous princess to matronly Spanish doña. One part of her will that was clear was that all her slaves – not including the people working on her encomienda – would be freed at the time of her death. This has caused some scholars in modern-day academia to label Doña Isabel an abolitionist or a heroine who championed the rights of the indigenous. It’s important to note that during her lifetime, Doña Isabel did not free a single slave, nor did she speak out against the practice which was something very well-accepted by her given her social status and lineage. Doña Isabel’s children became prominent in Mexico City and in Spain, and many of her descendants married into noble houses in Europe. The line of counts of Miravalle in Spain began with Doña Isabel’s son, Juan de Andrade Gallego Moctezuma who also inherited half of her enormous encomienda at Tacuba. Some researchers estimate that nearly 2,000 people in Spain alone are direct descendants of Doña Isabel or her sister.

Doña Isabel would not become a widow for the sixth time. She died in either 1550 or 1551 and her husband would live for more than 20 more years. Some historians consider her legacy to be more important than her life. As the legitimate inheritor of the Aztec royal family’s wealth, and as the last Aztec Empress, Doña Isabel left behind a sizable estate. This included land in various parts of New Spain, the gigantic encomienda at Tacuba, many slaves that she was allowed to keep under the Aztec nobility’s agreement with Cortés and untold amounts of gold and jewels. During her brief life, most of it under the protection of the Spanish Crown, Doña Isabel accumulated more wealth than what had been passed down to her through her noble inheritance. At the time of her death her estate was so vast and complex that it spent many years in litigation with various claimants contesting parts of her will. Doña Isabel’s long will is considered thoughtful and concise by historians and gives great insight into the character of this woman who seems to have made a seamless transition in her life from indigenous princess to matronly Spanish doña. One part of her will that was clear was that all her slaves – not including the people working on her encomienda – would be freed at the time of her death. This has caused some scholars in modern-day academia to label Doña Isabel an abolitionist or a heroine who championed the rights of the indigenous. It’s important to note that during her lifetime, Doña Isabel did not free a single slave, nor did she speak out against the practice which was something very well-accepted by her given her social status and lineage. Doña Isabel’s children became prominent in Mexico City and in Spain, and many of her descendants married into noble houses in Europe. The line of counts of Miravalle in Spain began with Doña Isabel’s son, Juan de Andrade Gallego Moctezuma who also inherited half of her enormous encomienda at Tacuba. Some researchers estimate that nearly 2,000 people in Spain alone are direct descendants of Doña Isabel or her sister.

As an Aztec princess the young Tecuichpoch Ichcaxochitzin witnessed history. As a young woman known as Doña Isabel Moctezuma, she participated in history. In death she helped propagate an interesting future. The vast legacy of Doña Isabel, the last empress of the Aztecs, has yet to be fully examined or appreciated.

REFERENCES

Prescott, William. History of the Conquest of Mexico. CreateSpace, 2016. We are Amazon affiliates. Buy the book on Amazon here: https://amzn.to/3JD3EfS