Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

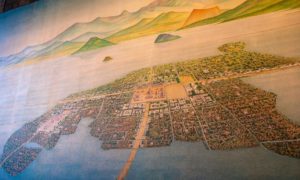

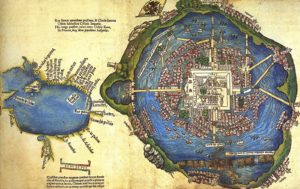

Today a great metropolis, Mexico City, sits atop the ruins of the destroyed capital of one of the most impressive ancient civilizations the world has ever seen. The Aztec Empire ruled over millions of people and had extensive trade networks reaching as far away as the modern-day American Southwest and the dense jungles of Central America. Everything flowed to the empire’s center, the magnificent city of Tenochtitlán, built on an island in the middle of Lake Texcoco in what is now the central part of the modern nation of Mexico. The Aztecs, who were once a wandering people, founded the city around 1325 when they saw an eagle atop a cactus eating a snake, which fulfilled an old prophecy regarding where they would settle down and build a great city. Even the founding of Tenochtitlán seems somewhat magical and whimsical if one believes in the legend.

Today a great metropolis, Mexico City, sits atop the ruins of the destroyed capital of one of the most impressive ancient civilizations the world has ever seen. The Aztec Empire ruled over millions of people and had extensive trade networks reaching as far away as the modern-day American Southwest and the dense jungles of Central America. Everything flowed to the empire’s center, the magnificent city of Tenochtitlán, built on an island in the middle of Lake Texcoco in what is now the central part of the modern nation of Mexico. The Aztecs, who were once a wandering people, founded the city around 1325 when they saw an eagle atop a cactus eating a snake, which fulfilled an old prophecy regarding where they would settle down and build a great city. Even the founding of Tenochtitlán seems somewhat magical and whimsical if one believes in the legend.

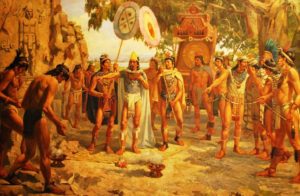

When thinking of the conquest of Mexico most people do not know that the Spanish entered the Aztec capital city of Tenochtitlán as invited guests. The Aztec emperor, Motecuhzoma Xocoyotzin, known to history simply as Emperor Montezuma, had a vast intelligence network throughout his empire that warned him of the arrival of the strange foreigners many days in advance. Immediately after hearing of the landing of the Spanish on the Gulf Coast, the Aztec leader dispatched emissaries to meet with the captain of the conquistadors, Hernán Cortés, to extend to him a warm welcome to Tenochtitlán. It is because of Montezuma’s hospitality that many accounts of the Aztecs as a living, breathing civilization survive to this day. Before things went terribly wrong, the Spanish spent months in the Aztec imperial capital during which time they observed, asked questions and wrote letters and diaries. This is precious information for modern-day scholars studying Ancient Mexico. It is from this valuable first-hand source material that we get a clear view of the majestic almost mythical Tenochtitlán.

An officer of Cortés, Bernal Díaz del Castillo, wrote a detailed account of his initial impressions of the city, a place where he, “saw things unseen, nor ever dreamed.” In the words of Bernal Díaz:

An officer of Cortés, Bernal Díaz del Castillo, wrote a detailed account of his initial impressions of the city, a place where he, “saw things unseen, nor ever dreamed.” In the words of Bernal Díaz:

“We proceeded along the Causeway which is here eight paces in width and runs…straight to the City of Mexico [Tenochtitlán]….It was so crowded with people that there was hardly room for them all, some of them going to and others returning from the city, besides those who had come out to see us, so that we were hardly able to pass by the crowds of them that came; and the towers and temples were full of people as well as the canoes from all parts of the lake.

Gazing on such wonderful sights, we did not know what to say, or whether what appeared before us was real, for on one side, on the land, there were great cities, and in the lake ever so many more, and the lake itself was crowded with canoes, and in the Causeway were many bridges at intervals, and in front of us stood the great City of Mexico….

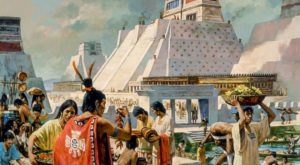

When we arrived at the great marketplace, we were astounded at the number of people and the quantity of merchandise that it contained, and at the good order and control that was maintained, for we had never seen such a thing before. The chieftains who accompanied us acted as guides. Each kind of merchandise was kept by itself and had its fixed place marked out. Let us begin with the dealers in gold, silver, and precious stones, feathers, mantles, and embroidered goods. Then there were other wares consisting of Indian slaves both men and women; and I say that they bring as many of them to that great market for sale as the Portuguese bring negroes from Guinea. They brought them along tied to long poles, with collars round their necks so that they could not escape, and others they left free. Next there were other traders who sold great pieces of cloth and cotton, and articles of twisted thread, and there were cacahuateros who sold cacao. In this way one could see every sort of merchandise that is to be found in the whole of New Spain. There were those who sold cloths of henequen and ropes and the sandals with which they are shod, which are made from the same plant. Sweet cooked roots, and other tubers which they get from this plant, all were kept in one part of the market in the place assigned to them. In another part there were skins of tigers and lions, of otters and jackals, deer and other animals and badgers and mountain cats, some tanned and others untanned, and other classes of merchandise….

When we arrived near the great Temple and before we had ascended a single step of it, the Great Montezuma sent down from above, where he was making his sacrifices, six priests and two chieftains to accompany our Captain. On ascending the steps, which are one hundred and fourteen in number, they attempted to take him by the arms so as to help him to ascend (thinking that he would get tired) as they were accustomed to assist their lord Montezuma, but Cortés would not allow them to come near him. When we got to the top of the great Temple, on a small plaza which has been made on the top where there was a space like a platform with some large stones placed on it, on which they put the poor Indians for sacrifice, there was a bulky image like a dragon and other evil figures and much blood shed that very day.

When we arrived near the great Temple and before we had ascended a single step of it, the Great Montezuma sent down from above, where he was making his sacrifices, six priests and two chieftains to accompany our Captain. On ascending the steps, which are one hundred and fourteen in number, they attempted to take him by the arms so as to help him to ascend (thinking that he would get tired) as they were accustomed to assist their lord Montezuma, but Cortés would not allow them to come near him. When we got to the top of the great Temple, on a small plaza which has been made on the top where there was a space like a platform with some large stones placed on it, on which they put the poor Indians for sacrifice, there was a bulky image like a dragon and other evil figures and much blood shed that very day.

When we arrived there Montezuma came out of an oratory where his cursed idols were, at the summit of the great Temple, and two priests came with him, and after paying great reverence to Cortés and to all of us he said: “You must be tired, Señor Malinche, from ascending this our great Temple,” and Cortés replied through our interpreters who were with us that he and his companions were never tired by anything. Then Montezuma took him by the hand and told him to look at his great city and all the other cities that were standing in the water, and the many other towns on the land round the lake, and that if he had not seen the great market place well, that from where they were they could see it better.

So we stood looking about us, for that huge and cursed temple stood so high that from it one could see over everything very well, and we saw the three causeways which led into Mexico, that is the causeway of Iztapalapa by which we had entered four days before, and that of Tacuba, and that of Tepeaquilla, and we saw the fresh water that comes from Chapultepec which supplies the city, and we saw the bridges on the three causeways which were built at certain distances apart through which the water of the lake flowed in and out from one side to the other, and we beheld on that great lake a great multitude of canoes, some coming with supplies of food and others returning loaded with cargoes of merchandise; and we saw that from every house of that great city and of all the other cities that were built in the water it was impossible to pass from house to house, except by drawbridges which were made of wood or in canoes; and we saw in those cities temples and oratories like towers and fortresses and all gleaming white, and it was a wonderful thing to behold….

After having examined and considered all that we had seen we turned to look at the great market place and the crowds of people that were in it, some buying and others selling, so that the murmur and hum of their voices and words that they used could be heard more than a league off. Some of the soldiers among us who had been in many parts of the world, in Constantinople, and all over Italy, and in Rome, said that they had never beheld so large a market place and so full of people, and so well regulated and arranged.”

After having examined and considered all that we had seen we turned to look at the great market place and the crowds of people that were in it, some buying and others selling, so that the murmur and hum of their voices and words that they used could be heard more than a league off. Some of the soldiers among us who had been in many parts of the world, in Constantinople, and all over Italy, and in Rome, said that they had never beheld so large a market place and so full of people, and so well regulated and arranged.”

All Spanish eyewitnesses concur in the astonishing splendor of Tenochtitlán. Even Cortés, the stoic commander of the Spaniards, was taken by the city’s beautiful gardens, magnificent architecture, and overall cleanliness. In a letter Cortés wrote to the Spanish king that survives to this day the awestruck conquistador wrote:

“The Indians live almost as we do in Spain, and with quite as much orderliness. It is wonderful to see how much sense they bring to the doing of everything.”

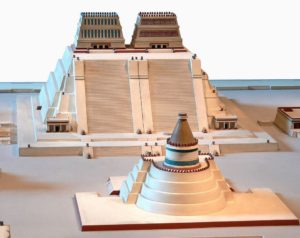

The island on which Tenochtitlán sat was connected to the mainland by a series of causeways and bridges on the north, south and west. As the city grew and the island springs either dried up or stopped meeting local demands, the Aztec emperors constructed aqueducts to carry fresh water to the city from miles away on the mainland. The aqueducts had two channels. One channel was always in use until it was time to be cleaned and then the Aztec engineers would switch the water to the secondary channel ensuring the uninterrupted flow of water to the capital. The causeways and the aqueducts were engineering marvels, but nothing compared to the buildings found in the heart of the city, at the civic-ceremonial center of Tenochtitlán. The great pyramid dominated the skyline. The magnificent structure was dedicated to the gods Huitzilopotchtli and Tlaloc who were respectively the god of war and the god of rain. The pyramid overlooked the large central plaza which is now Mexico City’s Zócalo, still one of the largest public squares in the world. There were dozens of public buildings and temples surrounding this great pyramid, which was not only the focus of the city but was the beating heart of the Aztec Empire. The nobles and elites, from the old Aztec nobility and from recently conquered client states, lived in the prime real estate zone near the center of the city. The largest noble residence was that of the emperor. Montezuma’s palace had over 100 rooms, including one of the largest private zoos ever to have existed. For more information about Montezuma’s zoo, please see Mexico Unexplained episode # 43. With its endless gardens featuring exotic flowers from far-flung parts of the empire to its decorative art objects throughout, the palace was a sight to see for the Spanish guests of the emperor. Imagine the reaction of the Spanish king when reading a letter penned by Hernán Cortés describing the emperor’s palace:

“Montezuma has a palace in the city of such a kind, and so marvelous, that it seems to me almost impossible to describe its beauty and magnificence. I will say no more than there is nothing like it in Spain.”

“Montezuma has a palace in the city of such a kind, and so marvelous, that it seems to me almost impossible to describe its beauty and magnificence. I will say no more than there is nothing like it in Spain.”

Even the humblest of homes in Tenochtitlán seemed to outdo anything of a similar status in Europe. The beautiful white-washed simple family residences came with interior courtyards complete with private flower and vegetable gardens. The common citizen had a high quality of life in the city

With large cities come large problems, and the rulers of the Aztec capital met nearly all their challenges using their sheer ingenuity. Tenochtitlán was divided into 4 districts and each district was divided further into 20 calpulli. Each calpulli had an administrator to take care of everything from repairing the streets to operating the public schools for the instruction of young boys. Almost every Spanish chronicler marveled at the cleanliness of the city, which was to a degree not seen in 16th Century Europe. One thousand men were in service to sweep, wash and smooth out the streets. One conquistador even mentioned in his diaries that the streets were so clean in Tenochtitlán that “you could walk about without fearing for your feet any more than you would for your hands.” According to the Spanish officer Bernal Díaz, the Aztecs had an interesting way to deal with sanitation. On every street they had public latrines much like outhouses or modern-day port-o-potties. The human waste was taken away and used in various ways. The Aztecs used it to tan hides and to provide fertilizer for the many public gardens. The system of chinampas, or floating reed-mat gardens on Lake Texcoco, also used the human waste to grow vegetables to provide nourishment for the capital’s citizens. Aztec municipal authorities set up a system of dikes and levees to guard against floods, but often during the rainy season the lake swelled up and briefly flooded the capital. Even without the lake, modern-day Mexico City still suffers from similar floods.

Even the person with the slightest interest in history knows what happened to this glistening imperial capital. Within 5 years of the arrival of the Spanish, the pyramids and temples were destroyed, the beautiful public gardens were demolished and most vestiges of Aztec society were wiped out. A new city was built on the ruins of the old, with Virgins replacing snake-headed gods and a strange new order imposed on the remaining population. The orderly capital of an empire that had not yet reached its full potential had been completely obliterated. Alternative history buffs often wonder what would have become of this mighty city and the Aztec Empire had the Spanish not arrived when they did. Five hundred years later modern Mexicans are left with scant remains of restored temples, museum artifacts galore and mere dreams of Tenochtitlán.

REFERENCES

Díaz del Castillo, Bernal. The Discovery and Conquest of Mexico. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1972.

Soustelle, Jacques. Daily Life of the Aztecs on the Eve of the Spanish Conquest. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1961.